To explore the elements involved in the process of paediatric palliative home care in the Spanish context according to the opinion of professionals.

MethodQualitative study based on Grounded Theory, adjusted to COREQ standards, using theoretical sampling with in-depth interviews (June 2021–February 2022) with paediatricians, paediatric nurses and social workers from paediatric palliative care units in Spain, excluding professionals with less than 1 years’ experience. Interviews were recorded and transcribed literally for coding and categorisation through a constant comparative process of code co-occurrence until data saturation using Atlas-Ti®. The anonymity of the informants has been guaranteed by using pseudonyms after approval by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Doctor Negrín (Las Palmas, Canary Islands) with registration number 2021-403-1.

Results18 interviews were conducted and 990 quotes were grouped into 22 categories of analysis and structured into four thematic groups (care, environment, patient and family, and professionals). The findings showed a holistic view emphasising the need to organise and integrate the factors involved in the home-based approach to paediatric palliative home care.

ConclusionsIn our context, the home environment meets appropriate conditions for the development of paediatric palliative care. The categories of analysis identified establish a starting point for further deepening the approach from the thematic areas involved: care, the environment, the patient and family, and professionals.

Explorar los elementos que intervienen en el proceso de los cuidados paliativos pediátricos domiciliarios en el contexto de España según la opinión de los profesionales.

MétodoEstudio cualitativo sustentado en la Teoría Fundamentada, ajustado a normas COREQ, mediante muestreo teórico con entrevistas en profundidad (junio 2021 - febrero 2022) a pediatras, enfermeras pediátricas y trabajadores sociales de unidades de cuidados paliativos infantiles en España, excluyendo profesionales con experiencia inferior a 1 año. Las entrevistas han sido grabadas y transcritas literalmente para su codificación y categorización mediante un proceso comparativo constante a través de coocurrencias de códigos hasta la saturación de datos usando Atlas-Ti®. Se ha garantizado el anonimato de los informantes empleando pseudónimos tras la aprobación por el Comité de Ética de la Investigación del Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Doctor Negrín (Las Palmas, Islas Canarias) con número de registro 2021-403-1.

ResultadosSe realizaron 18 entrevistas que expusieron 990 citas agrupadas en 22 categorías de análisis y estructuradas en cuatro grupos temáticos (cuidados, entorno, paciente y familia y profesionales). Los hallazgos mostraron una visión holística que enfatiza la necesidad de organizar e integrar los factores que intervienen en el abordaje domiciliario a los cuidados paliativos domiciliarios en pediatría.

ConclusionesEn nuestro contexto, el entorno domiciliario reúne unas condiciones apropiadas para desarrollar los cuidados paliativos pediátricos. Las categorías de análisis identificadas establecen un punto de partida para seguir profundizando en el abordaje desde las esferas temáticas implicadas: los cuidados, el entorno, el paciente y la familia y los profesionales.

Infant mortality has fallen in recent years due to the development of scientific knowledge, which has helped to improve survival rates and increased the prevalence of incurable and disabling diseases with severe and potentially lethal pathologies which require palliative care in paediatric ages. The majority of deaths occur in the first year of life, and they are mainly caused by congenital malformations, deformities and chromosome anomalies. After the first year of life, the most probable causes of death are neurodegenerative or neoplastic diseases.1 These may involve different organic systems or only a single system, with a degree of severity which requires specialized care and periods of hospitalization in a tertiary centre, affecting quality of life, limiting it and often jeopardizing it.2,3 Children and adolescents in these situations are at risk of suffering some type of physical, developmental, behavioural or emotional vulnerability, and they also require more and more complex care by health services.4 Given this reality, the general strategy should consist of using an individualized therapeutic approach which adapts to patient needs or state of health at all times.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines paediatric palliative care (PPC) as total active care of a child’s body, mind and spirit, while also supporting the family.1 Such PPC covers extremely fragile patients with highly complex diseases which do not respond to treatment, and who may die before reaching adult age; it is primordial for these patients to control their physical, psychological, social and spiritual symptoms.4 Multidisciplinary coordination of the team of professionals involved in achieving the therapeutic targets agreed with the patient and their family is therefore especially important, contextualizing PPC on the basis of the following principles:1

- •

PPC will commence when a life-threatening disease is diagnosed, and it continues regardless of whether or not the child or adolescent receives specific treatment for the disease in question.

- •

Medical professionals should assess and relieve the child or adolescent’s physical, psychological and social suffering.

- •

For PPC to be effective it is necessary to use a broad multidisciplinary approach that includes the family, using the resources that are available within the community; it may be applied effectively even when resources are limited, and it may take place in tertiary or community health centres, or even in the patient’s own home.

Fewer individuals receive PPC in Spain than adults who receive palliative care. This, together with the geographical dispersion of this population, has a major influence on the design and organization of PPC and the financing of the necessary resources.1,5

The National Health System (NHS) recognises the essential nature of PPC in the advanced stages of a disease or the end of life in care for children and adolescents, as well as their families.1 Nevertheless, the NHS has traditionally centred medical resources on hospital care, in spite of the fact that PPC in the home may be an effective approach for these patients in favourable socioeconomic circumstances,6,7 including their families in care processes.8 This scenario shows that there is a hospital-centred approach in more developed countries, and this also leads to the fragmentation of care as perceived by users, together with a high cost and limited impact on the health of the population.9

On the other hand, the emotional involvement of the family and carers in this population group hinders their acceptance of the irreversible nature of the disease and death, so that their grief is sometimes more complicated.1 Given this situation, it is quite possible that some family members may develop a prolonged period of mourning which becomes severe and hard to resolve, leading to the need to develop studies that try to respond to these needs within our context.10

The development of home PPC units may help to create a tie, so that the family finds an opportunity to achieve more capability and independence in self-care within their home environment, favouring humanized care and the reconciliation of family life with a minimum of professional intervention.10 Work to implement mechanisms that ensure proper coordination between professionals as well as between different levels of care has favoured the development of different professional profiles with clinical skills in the advanced care, monitoring and control of these patients;11 nevertheless, the social and medical care systems for home care are still fragmented, due to the lack of a map of social resources and restricted channels of communication for the transfer of patient information.11,12 For good quality and well-organized PPC it is necessary to know the preferences of a patient and their family respecting the place where they should receive proper care for their physical, psychological, social and spiritual needs in the final days of their life; in this way the PPC clinical practice guide1 proposes patient-centred care at all times in the process of a disease with the said characteristics, regardless of whether they are a complex chronic patient or one in palliative care, adapting or individualizing the therapeutic approach according to their needs or clinical situation; recommendations based on clinical experience and consensus should therefore be included, with aspects such as communication with the patient and their family, as well as the preferred location for end-of-life care.

Care models which are adapted to this complex situation have to be developed, to guarantee the health results in children and adolescents.13 More in-depth scientific knowledge is therefore required, to support and guarantee a suitable transition of PPC from the hospital to the home in these circumstances.

Due to all of the above-mentioned considerations, the general aim of this work is to explore the elements that intervene in the home PPC process in Spain according to the opinions of professionals. Its specific aim consists of identifying and describing the categories of analysis and core themes based on the discourse of the respondents.

MethodDesign: A qualitative study based on an inductive Grounded Theory paradigm14 (GT) with in-depth interviews conducted in Spain.

Researcher characteristics: Both researchers are men with academic training in paediatric nursing; the principal researcher (PR) (JSM) has 2 years of clinical experience in paediatric medicine and no experience in qualitative methodology, while the assistant researcher (AR) (CARS) has more than 15 years’ experience in paediatric medicine and also has previous experience in the use of GT and postgraduate training in qualitative methodology. The researchers have no personal links of any kind with the respondents, and only contacted them by electronic mail to recruit them and include them in this research.

Respondents: The target population are professionals in the different scientific disciplines (paediatricians, paediatric nurses and social workers). The selection strategy consisted of theoretical sampling to ensure that the different professional profiles were represented, until data saturation was achieved.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria: Professionals who work in the PPC units of different third level paediatric hospitals in Spain were included. Those with less than one year of experience in the field studied were excluded.

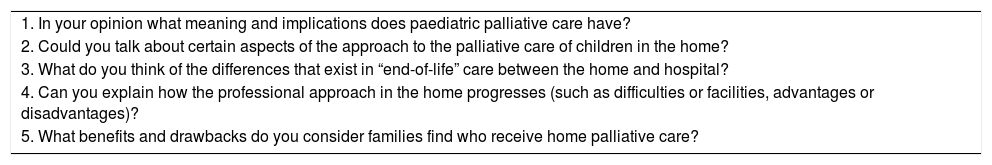

Access to the population: The PR administered all of the interviews from June 2021 to February 2022 in the workplace (hospital and primary care surgeries) or private homes of the respondents. The interviews were face-to-face or through the Zoom® platform, and they lasted for approximately 60min. A semi-structured guide was used for the interviews, and this is shown in Table 1.

Semistructured interview guide.

| 1. In your opinion what meaning and implications does paediatric palliative care have? |

| 2. Could you talk about certain aspects of the approach to the palliative care of children in the home? |

| 3. What do you think of the differences that exist in “end-of-life” care between the home and hospital? |

| 4. Can you explain how the professional approach in the home progresses (such as difficulties or facilities, advantages or disadvantages)? |

| 5. What benefits and drawbacks do you consider families find who receive home palliative care? |

Analytical process: The interviews were recorded and literally transcribed. After transcription thematic analysis of quotes or verbatim remarks took place to identify the analytical codes and categories which emerged from the data using an open coding process.15 The process of analysis followed the classic methodology proposed by Glasser & Strauss, which includes two aspects; firstly, Glasser proposes an emerging theoretical construction in which the findings are subjected to a constant process of comparison based on the social reality observed after each interview. Secondly, Strauss proposes a categorization process that starts with open codification by means of the successive review of the content of the interviews and field notes of the researchers, with the aim of identifying the descriptive codes grouped in the emerging and theoretical analytical categories until data saturation is achieved; comparative axial codification of the data from successive interviews is then carried out with the previous categories using code concurrence analysis; lastly, selective codification is performed by merging similar analytical categories, to select those which display greater grounding and identifying the core theoretical categories which explain the phenomenon;16 all of this using an approach based on the conceptual paradigm of Corbin & Strauss.17 Version 9 Atlas-Ti® software was used for analysis, and the results are expressed using semantic network diagrams, tables of concurrences and narrative explanations.

Methodological rigour: The structural and conceptual abstraction created by the process of codification and categorization increases the operative rigour of the data. Parallel to and simultaneous with the process of coding the verbatim remarks, the notes made in the field notebook of the PR during the discourse of the respondents were consulted to compare the information, to add rigour by triangulating the data gathering techniques. The research was conducted following the recommendations of the “Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research” (COREQ).18

Ethical criteria: This research followed the general principles which govern all studies in the field of health. All of the respondents were asked to give their verbal consent for audio-visual recording, guaranteeing their anonymity by the use of pseudonyms which help to classify the data without prejudice to their privacy and intimacy. The Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Doctor Negrín (HUGCDN), in the Province of Las Palmas (Canary Islands, Spain), approved the study with registration number 2021-403-1.

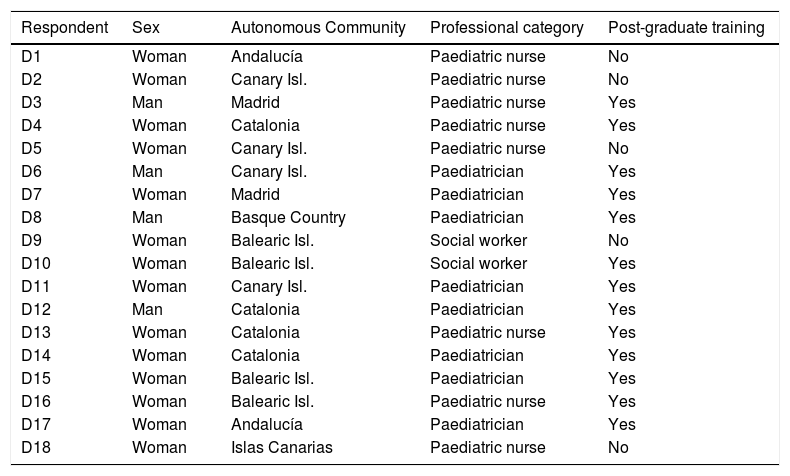

ResultsAlthough 20 professionals were contacted, finally 18 were interviewed as it proved impossible to make an appointment with the remaining two. The respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents.

| Respondent | Sex | Autonomous Community | Professional category | Post-graduate training |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | Woman | Andalucía | Paediatric nurse | No |

| D2 | Woman | Canary Isl. | Paediatric nurse | No |

| D3 | Man | Madrid | Paediatric nurse | Yes |

| D4 | Woman | Catalonia | Paediatric nurse | Yes |

| D5 | Woman | Canary Isl. | Paediatric nurse | No |

| D6 | Man | Canary Isl. | Paediatrician | Yes |

| D7 | Woman | Madrid | Paediatrician | Yes |

| D8 | Man | Basque Country | Paediatrician | Yes |

| D9 | Woman | Balearic Isl. | Social worker | No |

| D10 | Woman | Balearic Isl. | Social worker | Yes |

| D11 | Woman | Canary Isl. | Paediatrician | Yes |

| D12 | Man | Catalonia | Paediatrician | Yes |

| D13 | Woman | Catalonia | Paediatric nurse | Yes |

| D14 | Woman | Catalonia | Paediatrician | Yes |

| D15 | Woman | Balearic Isl. | Paediatrician | Yes |

| D16 | Woman | Balearic Isl. | Paediatric nurse | Yes |

| D17 | Woman | Andalucía | Paediatrician | Yes |

| D18 | Woman | Islas Canarias | Paediatric nurse | No |

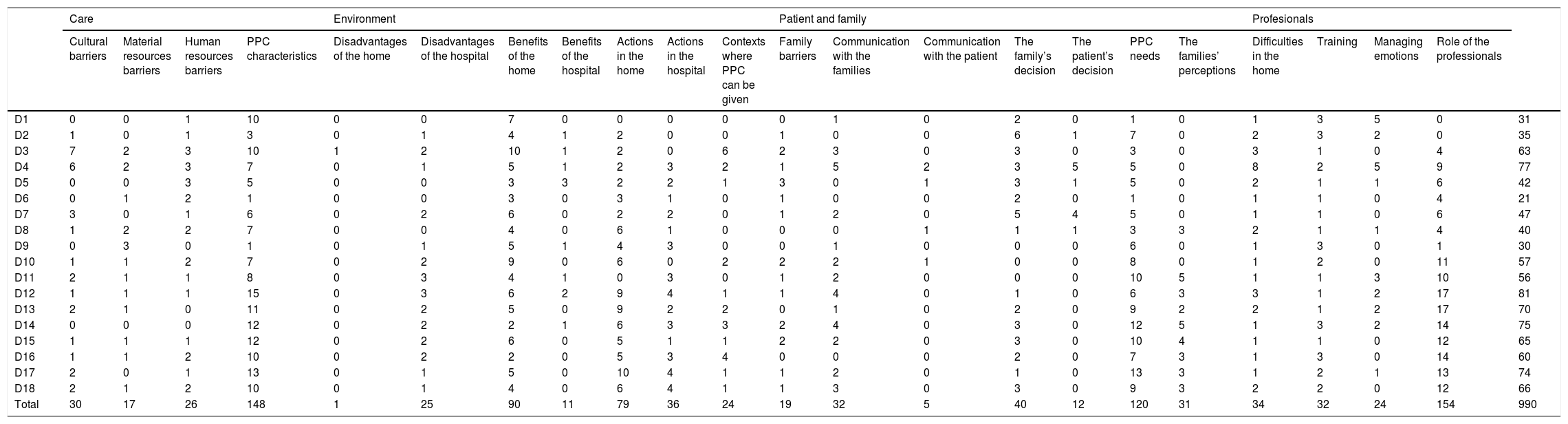

Analysis of the interviews identified n = 990 mentions that were codified and grouped in 22 analytical categories and structured in 4 main thematic groups: care, environment, patient and family, and professionals. The analytical category with the highest number of mentions was the “Role of professionals” (n = 154) followed by “PPC characteristics” (n = 148) and “PPC needs” (n = 120), as shown in Table 3.

Number of mentions, analytical categories and main themes in each one of the interviews.

| Care | Environment | Patient and family | Profesionals | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural barriers | Material resources barriers | Human resources barriers | PPC characteristics | Disadvantages of the home | Disadvantages of the hospital | Benefits of the home | Benefits of the hospital | Actions in the home | Actions in the hospital | Contexts where PPC can be given | Family barriers | Communication with the families | Communication with the patient | The family’s decision | The patient’s decision | PPC needs | The families’ perceptions | Difficulties in the home | Training | Managing emotions | Role of the professionals | ||

| D1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 31 |

| D2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 35 |

| D3 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 63 |

| D4 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 77 |

| D5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 42 |

| D6 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 21 |

| D7 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 47 |

| D8 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 40 |

| D9 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 30 |

| D10 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 57 |

| D11 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 56 |

| D12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 17 | 81 |

| D13 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 17 | 70 |

| D14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 12 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 14 | 75 |

| D15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 65 |

| D16 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 14 | 60 |

| D17 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 13 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 13 | 74 |

| D18 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 12 | 66 |

| Total | 30 | 17 | 26 | 148 | 1 | 25 | 90 | 11 | 79 | 36 | 24 | 19 | 32 | 5 | 40 | 12 | 120 | 31 | 34 | 32 | 24 | 154 | 990 |

PPC: Paediatric palliative care.

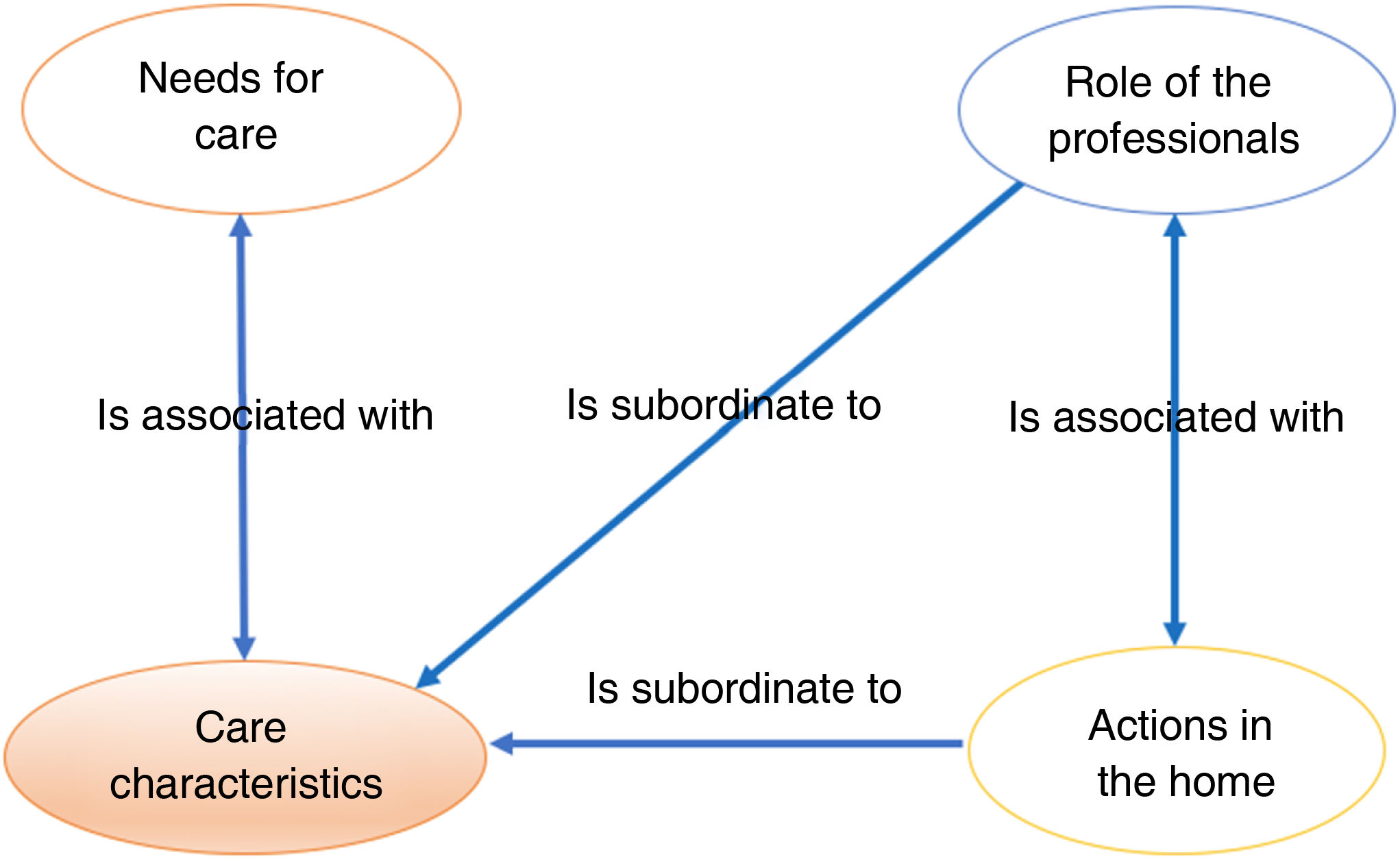

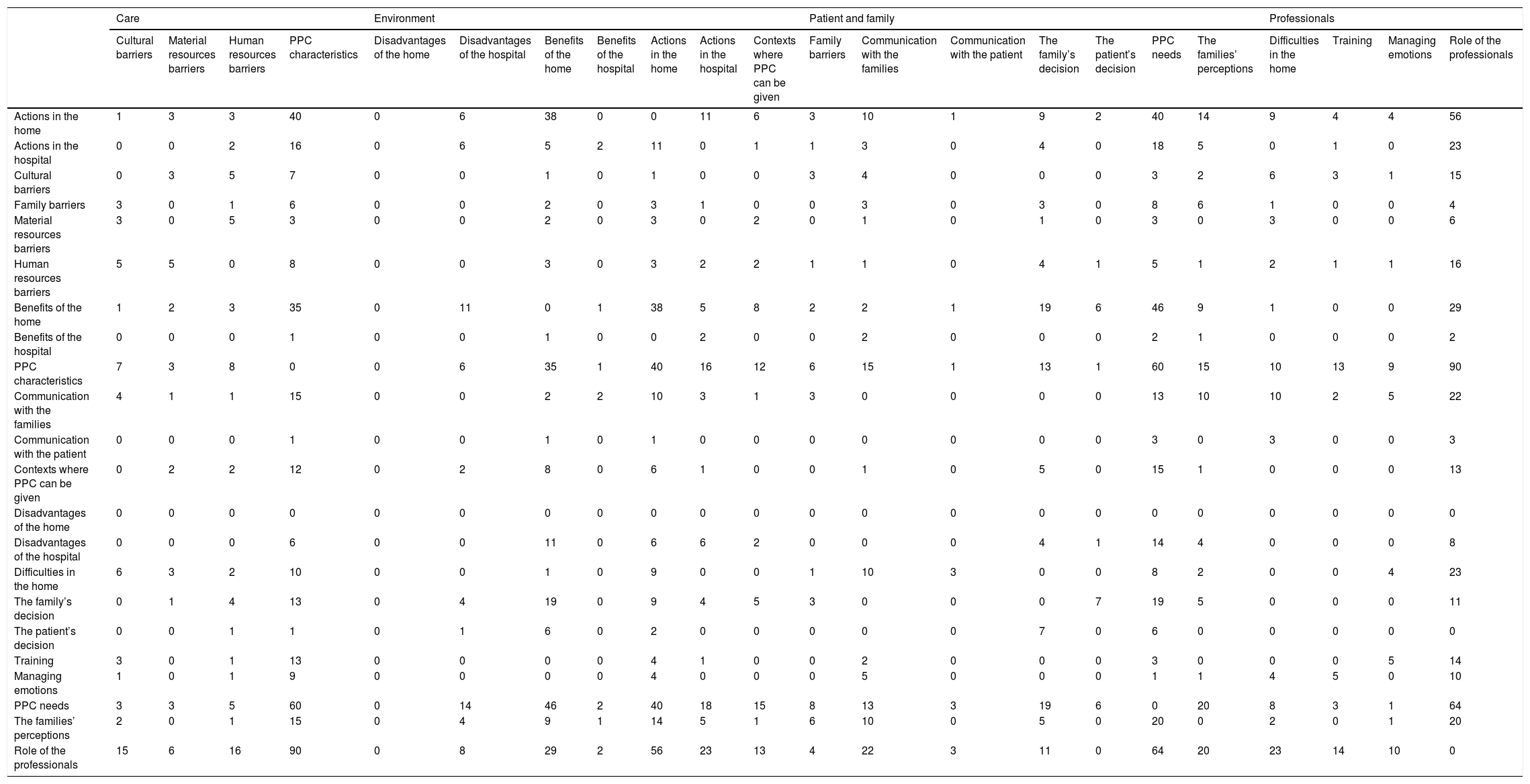

The analytical categories were organized in 5 groups, based on the frequency of their concurrences. They were then highlighted in ascending order from white (0 times), green (1–9 times), yellow (10–39 times) to red (more than 40 times). The highest number of concurrences was found between the codes of the analytical categories “PPC characteristics” and “Role of the professionals” (n=90). The concurrences between “Role of the professionals” and “PPC needs” came in second place (n=64), while “PPC characteristics” and “PPC needs” came third (n=60), followed by those between “Role of the professionals” and “Actions in the home” (n = 56), as is shown in Table 4.

Co-occurrences of codes between analytical categories.

| Care | Environment | Patient and family | Professionals | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural barriers | Material resources barriers | Human resources barriers | PPC characteristics | Disadvantages of the home | Disadvantages of the hospital | Benefits of the home | Benefits of the hospital | Actions in the home | Actions in the hospital | Contexts where PPC can be given | Family barriers | Communication with the families | Communication with the patient | The family’s decision | The patient’s decision | PPC needs | The families’ perceptions | Difficulties in the home | Training | Managing emotions | Role of the professionals | |

| Actions in the home | 1 | 3 | 3 | 40 | 0 | 6 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 6 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 40 | 14 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 56 |

| Actions in the hospital | 0 | 0 | 2 | 16 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 18 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 23 |

| Cultural barriers | 0 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 15 |

| Family barriers | 3 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Material resources barriers | 3 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Human resources barriers | 5 | 5 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 16 |

| Benefits of the home | 1 | 2 | 3 | 35 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 38 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 19 | 6 | 46 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 29 |

| Benefits of the hospital | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| PPC characteristics | 7 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 35 | 1 | 40 | 16 | 12 | 6 | 15 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 60 | 15 | 10 | 13 | 9 | 90 |

| Communication with the families | 4 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 10 | 10 | 2 | 5 | 22 |

| Communication with the patient | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Contexts where PPC can be given | 0 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 15 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| Disadvantages of the home | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Disadvantages of the hospital | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 14 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Difficulties in the home | 6 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 23 |

| The family’s decision | 0 | 1 | 4 | 13 | 0 | 4 | 19 | 0 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 19 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| The patient’s decision | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Training | 3 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 14 |

| Managing emotions | 1 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 10 |

| PPC needs | 3 | 3 | 5 | 60 | 0 | 14 | 46 | 2 | 40 | 18 | 15 | 8 | 13 | 3 | 19 | 6 | 0 | 20 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 64 |

| The families’ perceptions | 2 | 0 | 1 | 15 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 1 | 14 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 20 |

| Role of the professionals | 15 | 6 | 16 | 90 | 0 | 8 | 29 | 2 | 56 | 23 | 13 | 4 | 22 | 3 | 11 | 0 | 64 | 20 | 23 | 14 | 10 | 0 |

PPC: Paediatric palliative care.

The analytical category “PPC characteristics” occurred together with all of the other categories except for “Disadvantages of the home”, as the latter did not occur together with any other category. Outstandingly, the code for the category “PPC characteristics” occurred together with those for “Actions in the home” (n=40), “PPC needs” (n = 60) and “Role of the professionals” (n=90); this contributed to a graphic representation that expresses the paradigmatic professional approach to palliative care for these children and their families in the home, as shown in Fig. 1.

CareThe way in which PPC is provided in the home environment is largely influenced by the barriers in the social and cultural context in which it takes place; however, the quality of this palliative care in the home depends on the availability of human and material resources. In this respect the respondents expressed their dissatisfaction with the deficiencies which arise from management that does not favour the process of home care for this sector of the population. On the one hand, the spread of cultural barriers leads to a gradual transformation of personal customs as a result of the adaptations which take place in each social context. On the contrary, the barriers which are associated with restricted human and material resources can be transformed and made to fit the needs of this PPC in the home environment, as was found: D16: “We lack resources, we lack the people needed to offer 100% home care. I believe that lots of the things we do could be resolved if we had more resources at our disposal (…) we try to do a bit of everything, but the truth is we lack resources and a few more staff to be able to do everything well”. D8: “In fact, some studies have been published which show that the average cost of each stay in a home hospitalization unit is more or less one third of the cost in a hospital bed. So it’s not that it’s a saving (…) but those beds could be used and in fact they are used (…) for another type of patient, and that’s what makes it worthwhile (…)”.

In connection with the environment, the analytical categories identified cover the disadvantages, benefits and professional interventions within the hospital context and the home environment.

The respondents expressed feelings of rejection for the dynamic processes imposed by hospital regulations, as hospitals were even considered to be dehumanized environments. According to the respondents, PPC in the home favours a holistic approach to the needs of these patients. Incorporating the intrinsic benefits of experiencing a severe disease or end-of-life situation within the family environment: D12: “Well, in the hospital only the father and mother can be present (…) and they have other children (…) while in the home the other children can care for their sick sibling. (…) The whole family takes participates in the sadness of the moment, you know? Many parents think that if one child is admitted to hospital, the others cannot participate in the sadness, but kids notice that their parents are sadder, more tired, more stressed out (…) so the siblings need to be involved in this care and this moment in life that the family is immersed in”. D14: “(…) it should be encouraged, if the family can and want to be at home and it’s possible, then that shouldn’t be a limitation”.

Care in the home favours the creation of therapeutic ties which match the complexity of human relationships. These ties go beyond the morbid and biomedical aspects deriving from the pathological process, as the respondents said: D7: “It’s ideal for the person who is ill, or the ill person and their family, to decide where they should be, where they feel better”. D3: “When you visit a home you can’t believe the human behaviour you see, how they cry out for attention or don’t care about anything, or their fear that their brother will die. You see other realities. (…) If you want to give good holistic palliative care, then it’s fundamental to be able to visit their home, based on respect”. D12: “Well, I think that it’s the best there is (…) that the family opens the doors of their home just at the worst time of their lives, as it is fortunate and being able to enter where the child is. (…) Where the child lives, with their toys, teddy bears, photos, their life story (…) you know? Where the doctor and the nurse don’t feel so comfortable, as it isn’t their usual place of work, you know? But I think that it’s the best. Being able to be there (…) seeing the child’s everyday life, learning how things are, going to high class homes and being surprised, and going to low class homes and being surprised, too, if you understand what I mean, that in case of sickness, we’re all the same”.

Being at home may help the end of life to occur in suitable conditions, by showing families how to provide effective care: D3: “In my experience, they die a better death at home than they do in hospital. They die better at home than in hospital if they have a supporting team”. D14: “I think that the child can be at home, as far as is possible, if they have a home, if the family are able, if they want that and know. To the degree that it’s possible. But the truth is that there are cases in which they either don’t want that or can’t do that, so it’s important to be able to provide that care in the hospital. (…) It’s very important to individualize at all times. (…) It’s increasingly important to empower, for the primary care teams to be able to offer this possibility too, not only in the hospital; and being able to do so jointly”. D15: “In the hospital environment there are more factors that can, well that, create anxiety in the families and make the situation even harder than it is, but well, you try, we professionals are increasingly aware about the need to respect this moment and make it less uncomfortable (…) so the hospital isn’t so hostile for families and that if it (death) happens then to try to make sure that the patient and the family are as comfortable and with the least possible fear”. D16: “At the end, in the hospital, I think that on the one hand some families feel safer, because they are afraid they will not be able to control the situation at a certain time (…)”.

Information was offered on the possible advantages of home PPC, and these mainly centre on benefits for family conciliation: D4: “That they don’t have to follow timetables, that they can wear their comfortable cloths (…) and they don’t have to take turns to out down to eat, or for a family member to come in, and more now with covid”. D7: “(…) the private support of their closest loved ones in the family really helps a great deal. (…) They can receive visits by their closest friends, privately and more freely. (…) So, I think that when they receive company in their pain and desperation, as they’ve got more than enough of both, it’s a great help for them to be at home, sleep in their bed and cook their meals, shower in their own shower.”

The group of themes about the patient and their family includes analytical categories which cover family barriers and perceptions, as well as the capacity to choose, and communication with the patients and their families about their PPC needs in the home.

The respondents underlined the findings which centre on communication with the patient and their family, as they consider this to be fundamental for the success of PPC within the home; in this way, continuing with the process of treatment means that the team of professionals has to be able to support the family through a trust-based relationship: D4: “I think that what hinders this is need to have a resource, right? For someone to be able to help you to make it possible. When you don’t have anyone who can help you in this process, then I really understand that you feel helpless (…) and fearful and needing to use the hospital”. D2: “if the family feels safe, they feel cared for. They see that they can ask about doubts they feel at any time of the day or night (…), so they’ll surely prefer to be mainly at home rather than in the hospital.”

The moment at the end of life is a highly complex situation, and it includes personal demands that go beyond simply acquiring responsibilities in caring for a loved one. Taking part in the process of end-of-life care for a son or daughter creates a massive emotional burden that is full of situations that create fear and uncertainties when their child gets worse or suffers an acute episode: D5: “Yes, I think that there may be families who would not bring them home because of the simple fact that they don’t want them to die there. Because of memories, as it would be so massive”. D5: “(…) when a child is ending their days, they get very frightened and the first thing they do is to bring them to the hospital so that they die here.” D17: “Being at home has an influence, it makes everything easier and you can go to school, the teacher can come to your home, you can play with your siblings, you can carry on with your routines within the disease, and it is nothing like the hospital. The person who will care for the child will always be the mother, generally the mother, rather than a different nurse every day (…) you know. (…) The fears we health workers cause with our clothing, or (…) has nothing to do with it. They are far more relaxed there, they are happier”.

These experiences of pain caused by the suffering and closeness to death of a loved one give rise to certain barriers in the therapeutic process when the professional approach to each experience is not appropriate: D7: “The ideal is for the sick person, or the sick person and their family, to decide where they are best, where they feel better”.

The findings show that some characteristics of PPC are associated with different intrinsic aspects of professional activity, such as the specific training they receive to improve their skills. They mentioned different aspects connected with the vital importance of developing advanced skills in properly controlling the situations faced by individuals in the final process of their life. The respondents mentioned findings that link their training with reducing the difficulties faced in a home to the minimum: D12: “(…) you need training as it’s a highly specific field which not everybody can handle, to be able to deal with it and (…) not only at an academic level, but at a human level too, you know? You need to have lots of communication skills, lots of other skills (…)”. D10: “Really we’re saying that you have to know how to use the apparatus and know how they work, how they should be used, and also be able to check whether a family will be able to take on care in the home”.

In the same way, by acquiring these skills professionals increase their own capacity to control the emotions which necessarily arise in daily contact with extremely serious situations: D12: “For these families, these children and their families, I think that, as you know, they are very delicate times, times that are very (…) very tough, and the work is very hard at an emotional level, you know?” D4: “(…) I think that it’s the most complicated aspect of the work. Maybe because, well, at the end of the day working with death and with the, with kids, well it’s that they aren’t aware of it like we are, really (…) for me it is the most complicated aspect”.

At these times of personal vulnerability, the interventions of professionals in the home or in a hospital, include permitting and respecting family decisions, without forgetting that the final decision on how to deal with the disease has to be taken by the families themselves: D3: “The best thing is to listen to the family and know how they feel, what they want at that time. Because what I want today may not be what I want when the child really is dying”. D16: “(…) if we’ve been able to connect with the family and if we have supplied care in a proper way, I believe that at the end all of the families, if they’ve decided themselves where they want the death to occur, then there is always positive satisfaction. I think that more than the environment, which is very important, it’s that the family should take the decision about where it should be and in what circumstances, so eventually that will be a good death”.

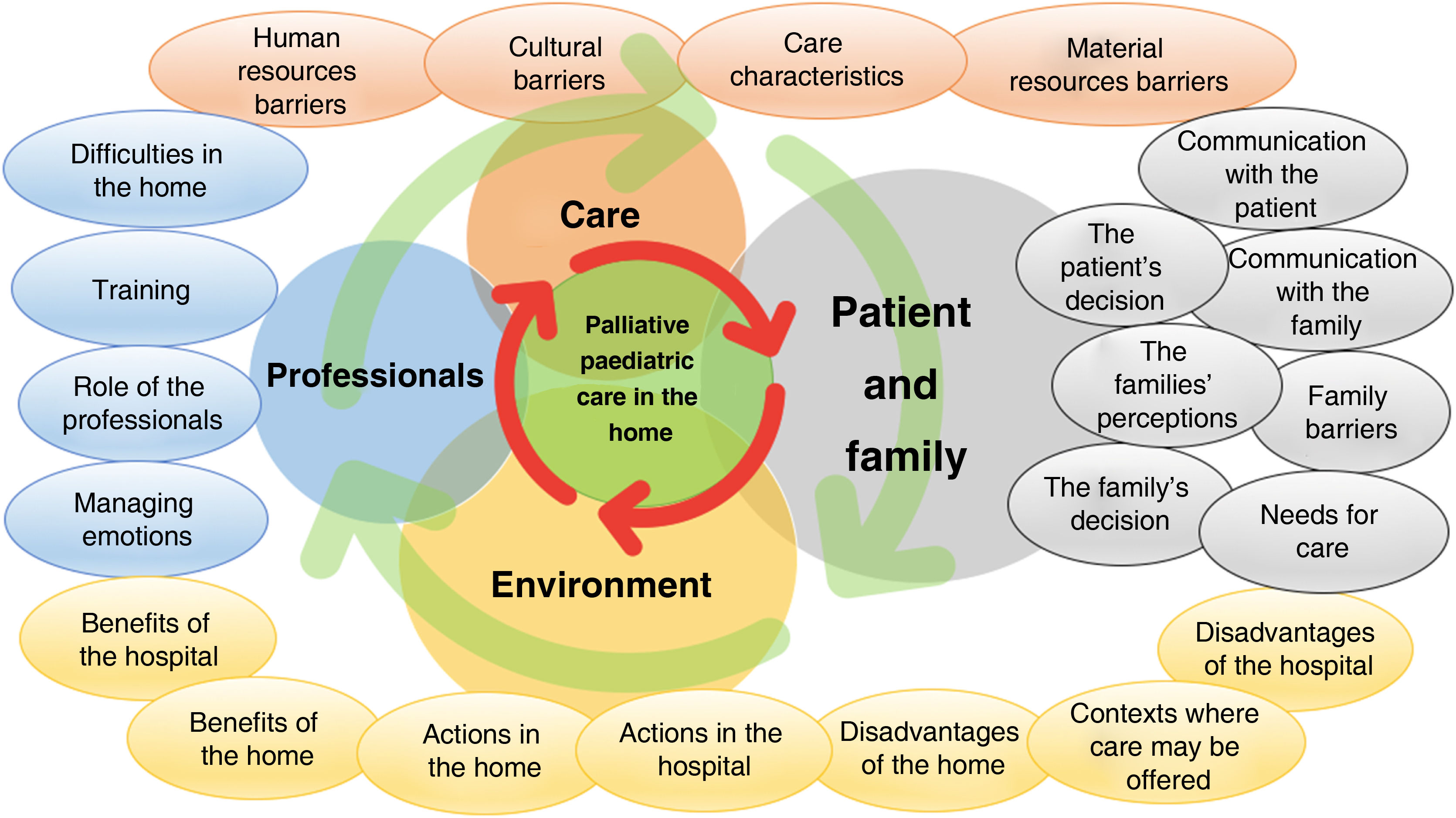

The information reported by the respondents contributed to findings which expressed a holistic view of PPC, emphasising the need to organise and integrate all of the factors which make it possible to improve the conditions of life for the patient and their family. This requires an approach to the situation of disease and the needs for care in the home in which the transdisciplinary team is properly coordinated. This has the aim of ensuring the child’s well-being and the quality of care for them and their family in an integrated and unfragmented care process, as may be seen in Fig. 2.

DiscussionThe analytical categories identified in this study show which elements are involved in home PPC through the route traced from nursing practice to conceptual models of nursing.19 Grouping these analytical categories into four main themes (care, the environment, the patient and their family and professionals) therefore involves three of the four core concepts of the nursing discipline (care, the environment and the person). This shows that the paradigm and nursing models are suitable for application within this specific clinical field. The findings defined the outstanding implications for developing quality clinical home practice in advanced paediatric nursing situations, based on the analytical categories included in each one of the core themes.

In connection with care the analytical category which identifies the nature and characteristics of PPC stands out. Although the latter are applied by a broad spectrum of professionals who use different methodological approaches, they have the shared goal of improving patients’ quality of life and that of their family by means of an active and dynamic approach which covers the time from the moment of diagnosis until the end of the process, with death and mourning.20

The environmental thematic group underlines the benefits of PPC within the home, which requires greater involvement by medical organizations. In the Canary Islands, the Palliative Care Strategy5 has yet to be fully developed; in connection with home PPC this document states that to achieve a quality standard this function has to be included in the portfolio of services. However, this specific aspect has not yet been implemented. When the development of these norms is compared with the national NHS PPC strategy in Spain,21 the level of legislative drive for this medical service is found to be insufficient. On the other hand, Gutiérrez and Ciprés22 focussed on the same research objective using a descriptive methodology similar to the one used in our study. These authors agree in stating that the selection of where to die should be a personal decision that increases the autonomy of an individual facing death. These clinically complex situations depend on the capacity of the professionals involved to manage the ties created with family members as well as the emotional experience.23

The patient and family thematic grouping emphasises the importance of guiding and focussing PPC in harmony with the personal needs of the individuals involved. The approach strategy used should be according to holistic models of palliative care, redefining PPC as the control of symptoms with an accessible and effective care team, where patients and their families are kept informed and where they acquire the capacity to be proactive.24

An outstanding finding in connection with the professionals is the need for them to acquire the necessary skills to play an effective role in home PPC. García-Trevijano et al.25 stated that to guarantee quality palliative care, different health systems must have strategies that include a duly organized team with the skills that are necessary for the needs of these patients. As was the case in our results, among other principal themes the qualitative study by Salins, Hughes and Peston24 identified the need to raise the skills of multidisciplinary teams for a successful therapeutic approach in the clinical context of therapeutic oncology. According to Hamre et al.26 the professionals themselves admitted the need to improve their training in palliative care, making it a fundamental aspect of providing proper care for children and their families.

No remarks by the respondents mentioned disadvantages in following-up the palliative process in the home, the traditional alternative to which is final process of dying in a less friendly environment such as a medical institution.27 The proposed the need for improvements to ensure that the experience of death is optimized by creating attractive hospital environments.28

On the other hand, the absence of two of the respondents who had been included at first did not give rise to the need to change our theoretical sampling, so that it was not necessary to examine and include new ones. This was because during the scaling up of the successive discourses no additional or relevant information appeared to explain the existing analytical categories or discover new ones to aid understanding of the phenomenon created by theoretical saturation.

The limitations of this research arise due to its exploratory nature. They are intrinsic to qualitative methodology, which does not yield evidence that can be verified, and the fact that its extrapolation is influenced by the singularity of death as a sociocultural expression. Nevertheless, this study has implications for clinical practice regarding the identification of certain analytical categories that make it possible to progress in the development, implementation and optimization of new home PPC strategies which meet the real needs of these patients and their families.

ConclusionsIn our context, the home environment has appropriate conditions for clinical paediatric palliative care. Patients’ needs can therefore be met in an ideal scenario that favours the therapeutic relationship with those families who are prepared to take on the emotional burden that the end of life involves. The analytical categories identified establish a starting point from which to continue gaining in-depth holistic knowledge of children’s palliative care needs. Such care will involve skilled and individualized palliative care that is adapted to the individual needs of each patient. This will have the purpose of amplifying the benefits of such care in the home, all based on the exploration of the different relevant thematic spheres: care, the environment, the patient and their family, and the care-givers.

FundingThis work received no specific grants from public, commercial or not-for-profit sector agencies.

The authors would like to thank the respondents who took part in the study for their generous and anonymous contribution.