Family process disruption is one of the main consequences of the hospitalization of a critically ill child in a Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU). Children’s visits to PICU may help improve family coping. However, this is not standard practice and nurses’ experiences in facilitating children’s visits to units where it is encouraged is unknown.

AimTo explore nurses’ experience related to promoting the visits of siblings to PICU.

MethodsAn interpretative phenomenological study was carried out through in-depth interviews in two PICUs belonging to third level public hospitals in Madrid. Twelve nurses with more than two years of experience in PICU were interviewed. They were all were working in PICU during the study. Furthermore, a PICU psychologist with an experience of four years was interviewed and this was considered shadowed data. Data analysis followed a thematic discourse analysis.

ResultsNurses’ experience of facilitating children’s visits to PICU can be condensed into four themes: emerging demand for visits, progressive preparation, decision-making through common consensus and creating intimate spaces.

ConclusionsThe experience of nurses in facilitating visits is mainly in response to the demand of families going through prolonged hospitalisation or end-of-life situations. The role of the nurse is one of accompaniment, recognising the major role of parents in the preparation of children and in developing the visit. Nurses feel insecure and lack resources for emotional support and demand action protocols to guide intervention and decision making.

La disrupción de los procesos familiares es una de las principales consecuencias de la hospitalización de un niño críticamente enfermo en una Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos Pediátricos (UCIP). La visita de los niños a la UCIP puede contribuir a mejorar el afrontamiento familiar. Sin embargo, no es una práctica habitual y se desconoce cuáles son las experiencias de las enfermeras en torno a facilitar la visita infantil a unidades donde se promueve.

ObjetivoExplorar la experiencia de las enfermeras en relación a la facilitación de la visita infantil a la UCIP.

MetodologíaEstudio fenomenológico interpretativo mediante entrevistas en profundidad. El estudio se desarrolló en las UCIPs de dos centros públicos madrileños de nivel IIIC. Participaron 12 enfermeras con experiencia en UCIP mayor de 2 años que, en el momento de la entrevista, prestaban servicios en dichas unidades. Además, se entrevistó a una psicóloga con experiencia de 4 años en UCIP cuya información se consideró en el contexto de los datos en la sombra. La información se analizó mediante un análisis temático del discurso.

ResultadosLa experiencia las enfermeras en relación a la facilitación de la visita infantil a la UCIP se puede condensar en cuatro temas: el emerger de la demanda, la preparación progresiva, la toma de decisiones desde el consenso y la creación de espacios de intimidad.

ConclusionesLas experiencias de facilitación de la visita responden, principalmente, a la demanda de las familias que viven hospitalizaciones prologadas o al final de la vida. El rol de la enfermera es de acompañamiento reconociendo la labor prioritaria de los padres en la preparación de los niños y el desarrollo de la visita. Las enfermeras se sienten inseguras y faltas de recursos para el apoyo emocional y reclaman protocolos de actuación que orienten la intervención y toma de decisiones.

The literature provides evidence on the impact of hospitalization of a critically-ill child on the family system. Disruption of family processes and compromised family coping are human responses that can develop as a consequence of the family’s lack of internal resources and support. This study has enabled us to further what we know about nurses’ experience of how they facilitate infant visits to Paediatric Intensive Care Units. The aspects identified were: where the demand originated, the preparation given to the children for the visit, and the activities implemented to facilitate and support [them in] the visit.

Implications of the studyThe findings of this study will inform strategies to facilitate infant visits to Paediatric Intensive Care Units, which should focus on fostering the appropriate practical context, empowering the family members to prepare and accompany their children, and implementing interdisciplinary programs and teams to support families.

The hospitalisation of a family member can be a disruptive event in the family dynamics, making it essential to adopt a family-centred approach where the individual and the family are considered as a “care unit”.1 We conceptualize the health of the family as a whole as the capacity for family resilience or the ability to respond or adapt to the different crisis situations that come up in the dynamics of life.2,3 The role of nurses (in this document, the term “nurse” is used in a generic sense and designates both men and women) in this context, is to promote the health of the various different members of the family, not focusing solely on the recovery of the sick individual, but also providing resources to all the components of the family unit to ensure the highest level of functioning.4 From this perspective, we accompany families in their processes of adaptation.5,6 There are different models and theoretical explanatory frameworks that enable us to conceptualize and justify our role of accompaniment during these processes. Some come from related disciplines such as Lazarus and Folkman’s stress coping model.7 Others situate us specifically in the reality of the nursing discipline, highlighting the Double ABCX model and McCubbing and Patterson’s Resiliency model of family stress, adjustment, and adaptation.5 According to these authors, the hospitalization of a family member is a powerful stressor that places the family system in a situation of vulnerability.

Within the family group, we will pay special attention to the healthy siblings of critically-ill children admitted to a Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (hereinafter, PICU). The literature alludes to their stressful experience during their sibling’s hospitalization in relation to their parents’ absence, changes in roles with respect to their care and protection, changes in daily life routines, and lack of information.8,9 With this premise as a starting point, they hypothesize that the presence of children at the bedside of their siblings may contribute to coping with the stressful situation.8,10 Along these lines, Van Horn and Kautz11 suggest working under the clinical judgment “disruption of family processes” by means of interventions such as facilitating visits that would include information, education, and participation of family members and loved ones in the care of the critically-ill child. The authors also recommend the level of anxiety and coping skills as outcome criteria to guide intervention.

To date, only some evidence can be identified that enabling visitation to the infant PICU is being implemented in some hospitals internationally.12,13 There are some reviews and expert recommendations based on opinion discourse, albeit no evidence has been found that reports on how this intervention is being put into effect or on the experience of caregivers and/or families with this intervention. Inasmuch as the latter is concerned, we can take some experiences in the field of neonatal intensive care14,15 and in adult intensive care units as a reference point.16–18 However, the nature of the clinical and family situation is very different from the one under consideration. This evidence gap is also highlighted by authors such as Boyer Hanley and Piazza19 and professional groups through position papers.20 Therefore, at this point in time, we are in a position to state that there is no contrasted information that sheds light on the experience of facilitating the infant visit to the PICU.

With this background, the general objective of the research was to learn about the nurses' experience in relation to facilitating infant visits to the PICU by attempting to: comprehend the perceptions and meanings attributed by the nurses to their experiences in relation to the infant visit, describe their experiences of accompaniment, and identify the needs and main concerns perceived in their experiences of facilitating infant visits to the PICU.

MethodDesignA hermeneutic or interpretative phenomenological study was carried out according to Heidegger’s proposal that was consistent with the intention of probing into how nurses interpret their professional work and endow this experience with meaning to this experience.21 It is from their individual narratives that we intend to access this knowledge regarding the phenomenon under study from the day-to-day experience in a social and daily work environment.22 On the other hand, the intersubjective relationship of the researcher with the object and process of research itself is assumed in the exercise of merging horizons.

Scope of studyThe study was carried out in the PICUs of the Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre and La Paz (hospitals with the highest level of complexity – IIIC). The paediatric services of these hospitals are especially committed to the philosophy of Family-Centred Care, a key point of the care activity being the humanization of care. In line with this philosophy, the two PICUs are open-door units so that parents or relatives can stay with their children 24 h a day, playing a fundamental role in the care of the critically-ill child. Both units care for children between the ages of 0 and 14 years with medical or surgical problems. They are equipped with 16 beds, respectively [sic], with an average occupancy rate of some 70% and a nurse/patient ratio of 1:2.

Study population and sampleThe study population was defined using the following inclusion criteria as a reference: nurses who, at the time of the fieldwork, were providing their services in the PICU; with more than two years of experience in the care of the critically-ill child and who, on at least one occasion, had facilitated an infant visit to the PICU.

To select the study sample, a purposive sampling by convenience was conducted based on availability and willingness to participate. Access to the participants was managed by the gatekeepers of each unit (nurse supervisor) whose role was to identify the nurses who met the inclusion criteria, provide them with information about the project, and manage the meetings with the main researcher-interviewer. Finally, we worked with a sample of 12 participants, considering that the information collected met the research objectives, reaching a point of saturation or informative redundancy.23

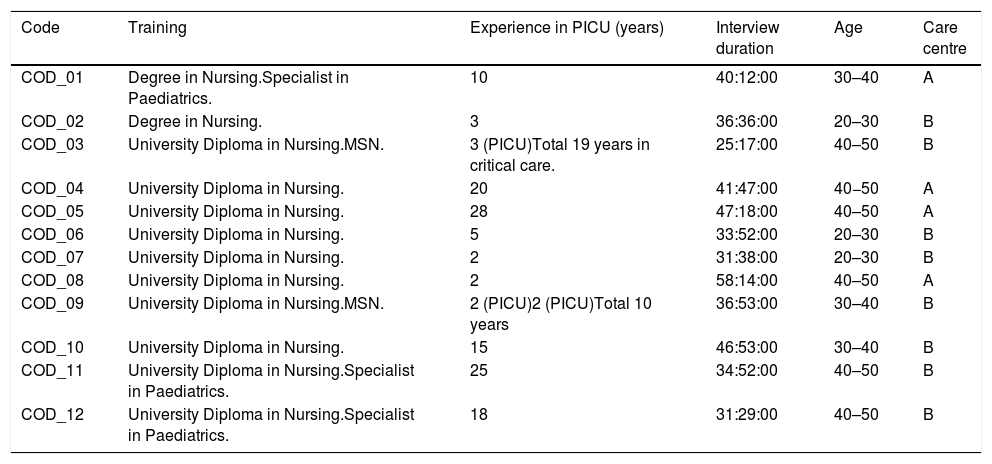

The study sample consisted of 12 nurses. At the time of the interview, all were working in the PICU, with a mean clinical experience of 10 years (2–27). Ninety-two percent were female with a mean age of 40 years. Only 25% were paediatric specialists (Table 1). In addition, we interviewed a psychologist with four years of PICU support experience at a third centre whose information was taken into consideration within the context of the shadow data and which served to analyse some of the experiences reported by the nurses in relation to psycho-emotional competencies with greater understanding. As advocated by Morse’s (2001) proposal, shadow data, or ‘speaking-for-others’, may be of interest as alternative data to drill down into the understanding or to work on the verification of findings.24

Participants’ characteristics.

| Code | Training | Experience in PICU (years) | Interview duration | Age | Care centre |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COD_01 | Degree in Nursing.Specialist in Paediatrics. | 10 | 40:12:00 | 30–40 | A |

| COD_02 | Degree in Nursing. | 3 | 36:36:00 | 20–30 | B |

| COD_03 | University Diploma in Nursing.MSN. | 3 (PICU)Total 19 years in critical care. | 25:17:00 | 40–50 | B |

| COD_04 | University Diploma in Nursing. | 20 | 41:47:00 | 40−50 | A |

| COD_05 | University Diploma in Nursing. | 28 | 47:18:00 | 40–50 | A |

| COD_06 | University Diploma in Nursing. | 5 | 33:52:00 | 20–30 | B |

| COD_07 | University Diploma in Nursing. | 2 | 31:38:00 | 20–30 | B |

| COD_08 | University Diploma in Nursing. | 2 | 58:14:00 | 40–50 | A |

| COD_09 | University Diploma in Nursing.MSN. | 2 (PICU)2 (PICU)Total 10 years | 36:53:00 | 30–40 | B |

| COD_10 | University Diploma in Nursing. | 15 | 46:53:00 | 30–40 | B |

| COD_11 | University Diploma in Nursing.Specialist in Paediatrics. | 25 | 34:52:00 | 40–50 | B |

| COD_12 | University Diploma in Nursing.Specialist in Paediatrics. | 18 | 31:29:00 | 40–50 | B |

MSN: Master of Science in Nursing.

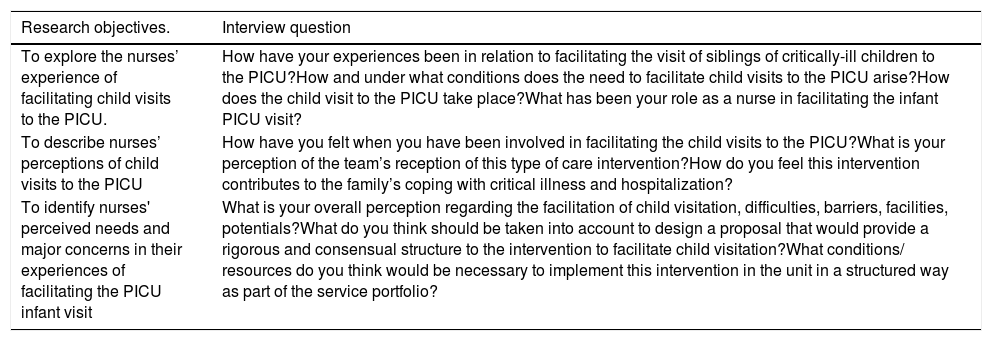

The semi-structured, in-depth interview was used as a data collection technique. This was understood as “repeated face-to-face meetings between the researcher and the informants aimed at understanding the informants’ perspectives on their lives, experiences or situations, as expressed in their own words”.25 The question guide was elaborated in line with the research objectives and the previous bibliographic review, in an attempt to guide the interviewer throughout the interview (although the interviewer’s attitude always ensured the self-determination of the participants to freely orient their discourse towards those dimensions they considered significant) (Table 2). The interviews were conducted by the principal investigator at the hospital, facilitating the informants’ participation without entailing a high personal cost. During the interviews, notes were taken in the form of field notes with those aspects of the discourse that required clarification or suggested a deeper understanding of the discourse. At the end, certain sociodemographic data were collected that were deemed relevant to contextualize the discourses (Table 1). The interviews lasted an average of 40 min and were audio-recorded (with the participants’ consent) for subsequent transcription and analysis. Both the audio recordings and the transcriptions were kept in the custody of the principal investigator, who ensured the confidentiality of the data and their anonymity.

Interview guide.

| Research objectives. | Interview question |

|---|---|

| To explore the nurses’ experience of facilitating child visits to the PICU. | How have your experiences been in relation to facilitating the visit of siblings of critically-ill children to the PICU?How and under what conditions does the need to facilitate child visits to the PICU arise?How does the child visit to the PICU take place?What has been your role as a nurse in facilitating the infant PICU visit? |

| To describe nurses’ perceptions of child visits to the PICU | How have you felt when you have been involved in facilitating the child visits to the PICU?What is your perception of the team’s reception of this type of care intervention?How do you feel this intervention contributes to the family’s coping with critical illness and hospitalization? |

| To identify nurses' perceived needs and major concerns in their experiences of facilitating the PICU infant visit | What is your overall perception regarding the facilitation of child visitation, difficulties, barriers, facilities, potentials?What do you think should be taken into account to design a proposal that would provide a rigorous and consensual structure to the intervention to facilitate child visitation?What conditions/ resources do you think would be necessary to implement this intervention in the unit in a structured way as part of the service portfolio? |

Qualitative data analysis was performed following Amadeo Giorgi's proposal for thematic discourse analysis,26 which can be summarized in the following steps: careful listening and comprehensive reading of the information to obtain an overall idea of the discourse; identification of the significant discursive elements in relation to the research objectives; regrouping and reflection through analytical memoranda on the units of meaning, and the relationship of these reflections for the elaboration of an explanatory narrative that accounts for each of the identified themes. For the organizational part of the analysis (identification of significant elements and their regrouping), Atlas-ti® software version 7.5 was used as a support tool. Subsequently, in the more interpretative phase, we worked in a traditional manner to elaborate networks of relationships and narrative and diagrammatic memoranda.

In the last phase of the analysis process, the findings were shared with two of the participating members of the research team with an academic profile, with their critical vision, in a triangulation of analysts. Subsequently, a meeting was organized in which the findings were presented to the collaborators of the clinically oriented research team. They gave their feedback and made comments to clarify some issues as an internal audit. Finally, the principal investigator has maintained, throughout the data collection and analysis work, an attitude of constant reflection on the way in which her preconceived ideas and assumptions may have played a part in the research process.

Ethical considerationsThe research project was evaluated by the Research Committees of both hospitals, considering that it met all the requirements in terms of scientific quality, feasibility and appropriateness, and did not require approval by the ethics committee given the scope of the research and the regulations in force. The participants were adequately informed during recruitment and this information was reinforced before the interview to guarantee self-determination in signing the consent for participation. The information provided was anonymized by coding. When presenting the experiential characteristics of the sample, relevant information was omitted so as to preserve the anonymity of the informants.

ResultsThe nurses’ experience with respect to facilitating child visitation can be synthesized around four themes: emerging from demand, progressive preparation, creating spaces for privacy, and consensus-based decision making.

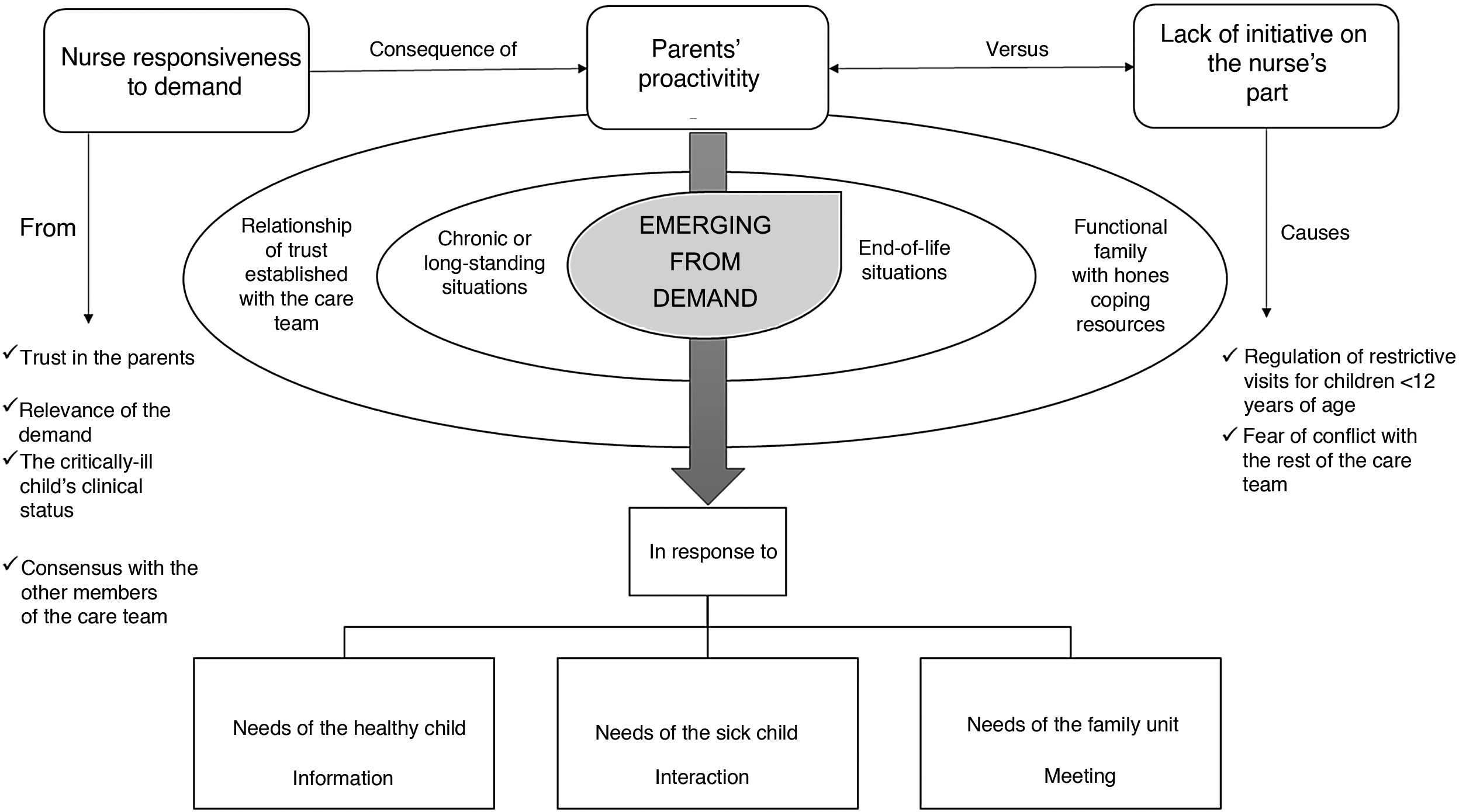

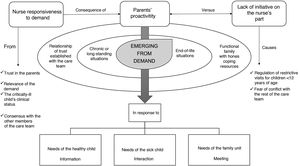

Emerging from demandEmerging from demand refers to the circumstances from which it generates and how the possibility of facilitating children’s visits to the PICU is proposed (Fig. 1). The nurses’ account reveals that the possibility of facilitating children’s visits to the PICU stems from the parents’ proactivity. This proactivity contrasts with the lack of initiative of the nurse who, as a result of their own initiative, only occasionally offered the families the possibility of one of their paediatric-aged members to visit the critically-ill child who has been admitted to the PICU. “She was a child who had younger siblings; the parents asked us, because it was a prolonged admission […]. They asked us if the siblings could come […]. and, in addition, it tends to be a little because the parents demand it” (COD_09).

This lack of initiative on the part of the professionals has to do primarily with the fear of getting pushback from the rest of the care team in the context of an environment where the visiting regulations only allow access to people over 12 years of age and where there are no formal, structural proposals to endorse or support decision-making. This idea is reflected in the following quote: “I don't know if we are afraid to offer because we don't know if we are the ones who can offer that option. Since it is not something that is stipulated in the service, you have to ask for permission from everyone else (to see if it is okay for parents or siblings to come in)” (COD_01).

The latter notwithstanding, the nurses express the fact that, when parents make the need of the family unit to participate in the PICU infant visit explicit, professionals are receptive to the demand, mobilizing resources to respond to it, taking as a reference four fundamental principles: the relevance of the demand, the clinical situation of the critically-ill child, the relationship of trust established with the parents, and the consensus of the other members of the care team. “Well, at the beginning, it was a source of confusion because we had never been faced with the situation of such a young child coming to see his sibling. Then, doubts arise as to how to act: what should I do, should I let him in… because rules are rules. Sometimes you have to be a little more flexible, depending on the situation, on the type of child” (COD_02).

Although the demand generally stems from the parents, it is important to reflect on the characteristics of the families that articulate this demand to the care team. In this sense, the informants allude to the fact that they are families who are going through exacerbations in the context of chronic health issues-diseases, acute health problems with very long PICU hospital stays or end-of-life situations. “There are few occasions when siblings have come. I would say that there have been two reasons: one, because the children have been in the PICU for a very long time and the other one, which is more traumatic for us, is when they are going to die, to say goodbye” (COD_03).

These situations are considered as relevant in comprehending that the family unit as a whole can benefit from the intervention, in terms of improving family resilience, the ability to cope with problems, expressing feelings and emotions among the members, and the opportunity to generate spaces to share and participate in the process of accompanying and caring for the critically-ill child. In contrast, situations in which the sick child is in an acute situation with significant decline or deformity of their body or has a number of bloody technical procedures that may visually impact the visiting child [underage sibling visitation] is not deemed pertinent. “Then it depends on the patient we have. If we have a critically-ill patient who is sedated and so on, the need for the sibling to visit seems dispensable to me […] If the patient is in a critical situation, sedated, with lots of wires, with many tubes or so on, I’m challenged to find the benefit of that child seeing their sibling. I think it is an image that is engraved on their memory, and it is not a pleasant one” (COD_10).

Furthermore, it should be noted that these are families with whom the nurses acknowledge having established a relationship of trust and that are characterized by being functional and by having developed adaptive coping skills. With respect to the relationship of trust, this is understood by the participants as a two-way relationship in which credibility is established in the other that creates a sense of safety when delegating decision-making and care, as reflected in the following verbatim: “Because they trust you. I think that spawns a fundamental relationship of trust. And they see that you care about their child and that you care about them as parents. This makes them trust you. Oftentimes, they didn’t even think about going home to sleep and, in the end, they value that their child is in a safe place with safe people and that they can go home to rest. So, I think it is very important, of course” (COD_09).

It is in this situation of mutual trust, where professionals consider that: parents share their psycho-socio-emotional needs with the certainty that they will be well received; and that they respond to the demand with the certainty that the family will make the most of the visit with remarkable achievements.

In this context of adaptive capacity on the part of the petitioning families, the request for child visitation arises, according to the nurses, based on three circumstances: the needs of the healthy child, the needs of the critically-ill child, and/or the needs of the family unit as a whole. Normally, the needs of the healthy child are limited to the lack of information and the imagined re-interpretation of what is happening to their sick sibling, giving rise to anxiety about death and permanent separation. Other times, the request arises from the hospitalized child themself, who needs to relate to his siblings. Finally, there are needs that arise from an integral perspective, i.e., with the aim of meeting the needs for interaction, support, and consolidation of family system itself. “The child we have now admitted (for example), (the parents) have asked us for an older sibling to come and see him. The mother comments that he asks about his brother every day. So, I think that children, at the end of the day, until they see it… they don't quite believe it, do they?” (COD_2).

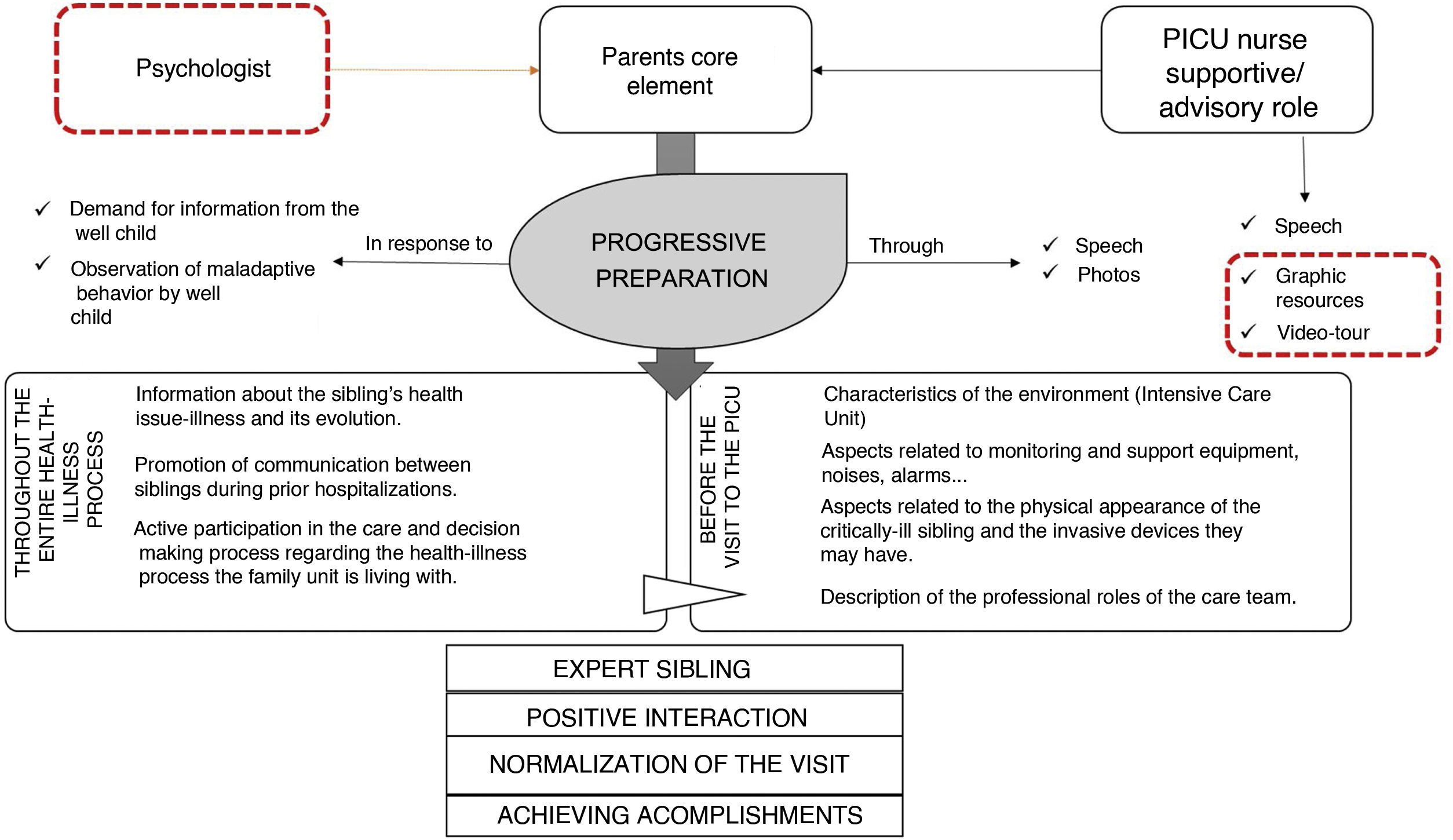

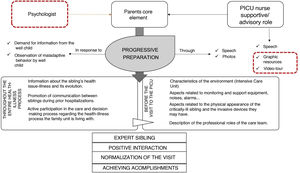

When considering the visit of a child to the PICU, they need to be prepared ahead of time. The nurses comment that, in this preparation, the parents play a major role in what they consider to be a process of “progressive preparation” (Fig. 2).

‘Progressive preparation’ refers to the work involving information and realization of the health-illness situation that parents do with their healthy children throughout the period of illness and that puts them in a position to be able to visit the PICU. One example can be seen in the following quote: “Yes, the parents would send him pictures of his sister, with the tube, and they would tell him how his sister was doing and explain to him, “Well, she has a tube in her mouth, she has a lot of wires like this around her arms, you are going to see her […]” (COD_01).

Generally, this preparation that parents carry out with their healthy children is a response to the latter’s explicit demands for information. On other occasions, the demands are implicit and it is the parents who, when they observe behavioural changes in their children, identify this need to be informed.

According to the nurses’ narratives, the information that parents provide to their children tends to focus on aspects having to do with the health issue-illness and its evolution. This information leads parents to promote activities that facilitate communication between the healthy child and the sick sibling, as well as participation in small care activities and decision-making. Prior to entering the PICU, this information is reinforced with more specific aspects regarding what the unit is like, the equipment they are going to see, the invasive devices their sibling is wearing/ carrying, and the roles of the professionals who care for him/her.

For their part, the professionals refer to adopting a supportive and advisory role, in this scenario, consolidating and contributing with specific information with a view to the visit to the unit. They acknowledge the limitation that some parents may have when performing this informative role. However, they do not allude to the need for the nurse to evaluate this performance capacity on the part of the families. When it comes to this accompaniment, they admit that they count on what they say as their sole instrument and support tool, mentioning other possible resources as potentially useful, like photos, stories, brochures, or even other graphic resources, such as a video tour of the PICU.

Another significant resource they mention is the figure of psychologists in whom they perceive tremendous potential when it comes to assessing families and their ability to cope with and manage the health-illness process, as well as for training the nursing team in communication skills, interpersonal relationships, and accompaniment. “I have sometimes sought out the psychologist from -association X- […] they do us the favour of talking to the parents and guiding us a little. I think that, perhaps [if] I say one thing, I’m making them miserable, you know what I mean? I am not a psychologist. We may be doing it with the very best intention in the world, but we are not doing such a good job of it, or not use the right words or [say them] at the right time” (COD_04).

Finally, from the nurses’ perspective, this process of progressive preparation enables the siblings to face the visit from a position of expert caregivers in most of the cases reported (chronic situations or prolonged admissions). From this position, the visit transpires normally and naturally, as witnessed in the following discursive fragment: “[…] It was a fairly prolonged admission. The sister ended up acting like a parent. She spent time with her here as an adult […] She even left school during that period of time, because she had stated that she knew that her sister was going to die and that it would help her to spend those last moments, those last days, months, whatever” (COD_02).

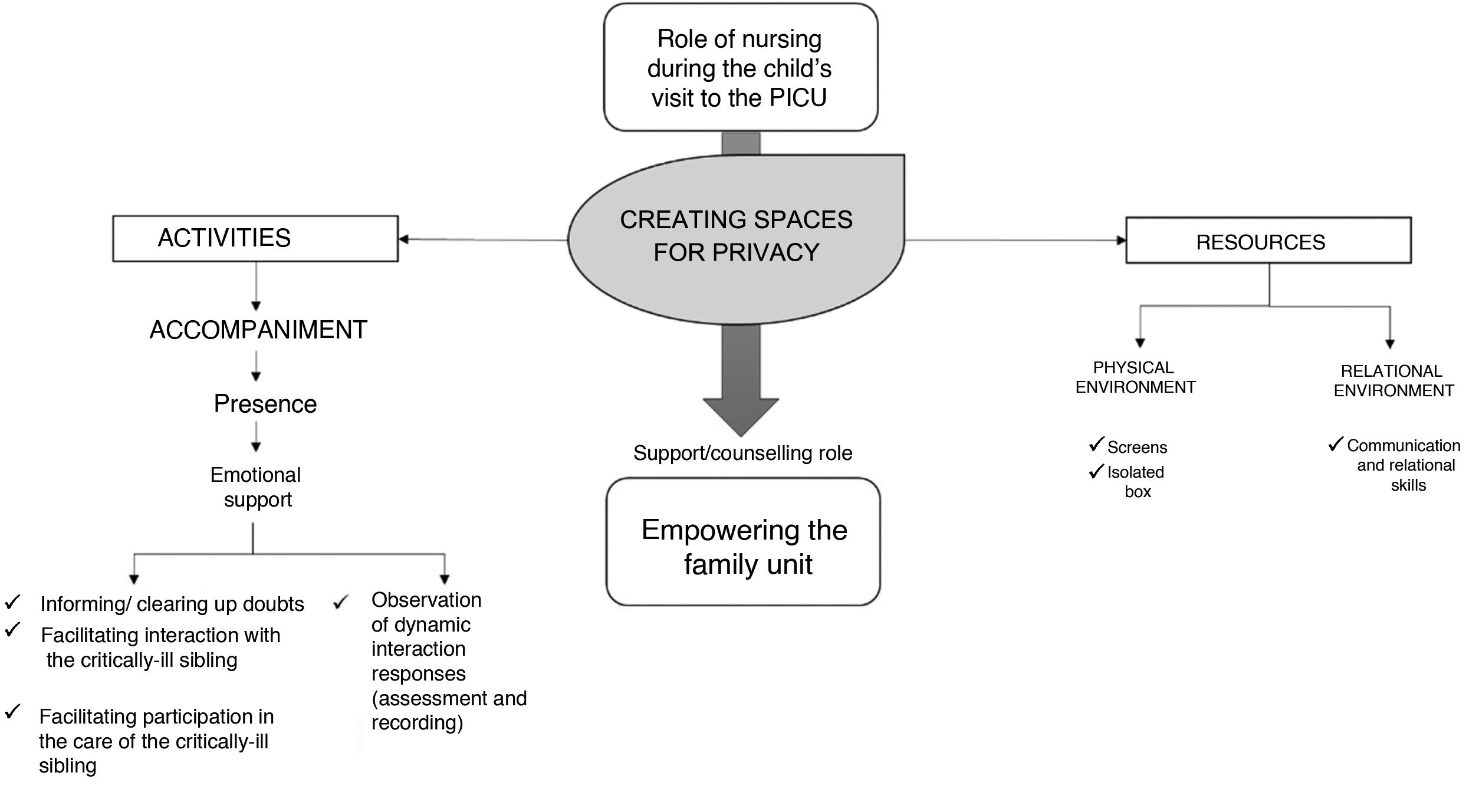

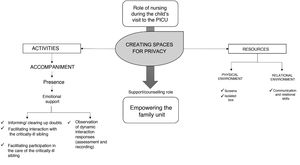

During the children’s visit to the PICU, the nurses limit their role to that of “creating spaces for privacy", understanding these spaces as environments with virtual limits where the focus of attention is the family unit and its relational potential (Fig. 3). “And then, well, you try to accommodate the space a little bit: a chair, some armchairs… you adapt the place a little bit and you leave them peacefully and in privacy […] I believe that you can create a comfortable, private environment with the resources we have” (COD_07).

The nurses’ narrative provides an account of the structural limitations of the units to facilitate isolated spaces where the family can have a private meeting. Sometimes, the use of screens or the possibility of using isolation boxes can foster this privacy. However, they point out that it is the interpersonal skills and therapeutic communication that manage to promote real spaces of privacy that can be characterized as “relational spaces”. “I try to give them space, so to speak, so that at the end… because it is a time for being together and such, but, of course, we are always on top of things at the box and for whatever they need” (COD_06).

The professionals express concern about being respectful in their support. To this end, they make use of presence (understood as being available to the family and their needs, attentively observing the expression of their demands from the background and giving confidence and support resources to the family unit so they can manage the meeting by themselves) and informative and emotional support, considering that, all of this contributes to diminishing and controlling fear and anxiety, promoting and facilitating the [healthy] child’s interaction with the critically-ill sibling through play or by performing small care activities. “(It’s a matter of) orienting them and seeing if they need anything… to be a little attentive […] as well as helping them: that, if they have come in to play, well, that they focus on this, that they not dissipate into something other than the sibling […] Well, just like if a parent gets scared or asks you… always be present and see how it goes… see what their reaction is, that of the child who is in bed and that of the one who comes in. Be there” (COD_05).

They also identify certain elements with room for improvement such as recording the observations made during the family interaction, as well as evaluating the achievement of the outcome criteria previously established with the family from their own subjectivity after the visit and later on, over a more long-term period. In addition, giving priority to relational aspects, the nurses refer to the fact that further training would be necessary to acquire a more competence in this area, acknowledging that they are very vulnerable in this respect, as revealed below. “[…] It wouldn't be a bad idea for us to receive some training because often times we try to act as psychologists, and you get sued, and we don’t get anywhere. So, it wouldn't be bad if we were instructed on how to prepare this situation and prepare it a little bit among all the professionals who are in charge of this child” (COD_07).

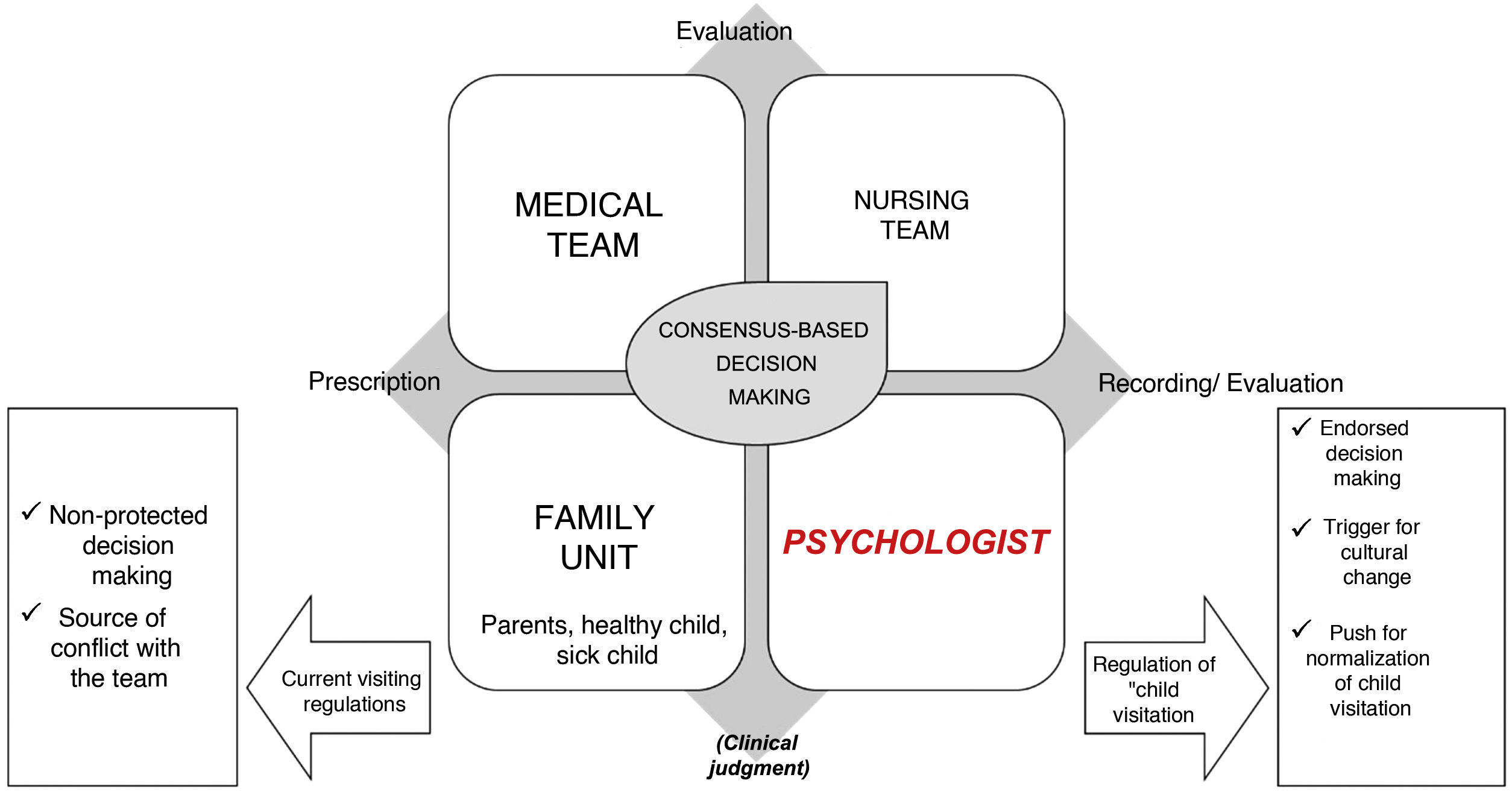

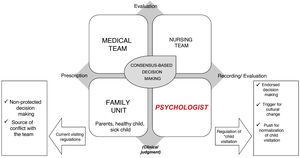

When it comes to making decisions regarding the relevance of the child’s visit to the PICU, the participants favour integrated and multidimensional decisions in which the different voices involved in the care process participate (Fig. 4). Thus, based on what they say, both the medical and nursing teams and the family unit itself (parents, healthy children, and the critically-ill child) would be part of a consensual decision-making process. However, there is sometimes a feeling of helplessness in determining the appropriateness of the visit. They mention the “good work” and the “good harmony of the team”, but they regret not having a regulation and protocol that support the team and avoid conflict between professionals. On the other hand, they point out that the possible participation of a psychologist in the care team is key, as they have competencies aimed at helping the other professionals and the family itself to analyse suitability of the visit and in carrying out the support. “Let's see, no… my idea is not that it could have negative consequences, but that we must take care of the patient’s need. So if… that is, if they do not feel like visiting, we should respect that they do not feel like visiting; i.e., there are times here that we have had children who have been asked, “Do you want X to come in?” and they have answered, “No” (COD_11).

In addition, they comment that decision making should be supported by an assessment of the overall situation (the status of the critical child, characteristics of the family, resources of the therapeutic team…) so that there is a clinical judgment that justifies the prescription of the intervention and individualised planning for each family. Regardless of identifying this need, the nurses refer to the fact that the assessment is not conducted according to a shared frame of reference and that there is no record of the assessment to ensure continuity of care. In this regard, once again, they insist that the protocolization of the intervention would go a long way to giving visibility and rigour to what is done intuitively and without resources. This would contribute to promoting a cultural shift and normalizing child visitation. “There should be a protocol to guide us. Because as each one of us has… we have different values, beliefs, a different way of working… what cannot be is that in one shift they decide one thing and in the next one, something else. This creates a lot of confusion for the parents […]” (COD_09).

As to the limitations concerning the visit, the nurses point out first and foremost the seriousness of the critical child who needs highly technical support and multiple invasive elements, as well as the fact that the visiting child has some kind of infection at the time of the visit. “Yes, there are times when they are going through certain situations, that it makes you feel bad even when the parents come in, you say, “My God, please (open chest, cannulas in place, the machine…), why on Earth do they have to go through this?” (COD_08). “A three-year-old with a cold cannot come, maybe the brother who is in bed wants to see him, but a three-year-old child who has a cold cannot come” (COD_12).

In any case, the participants recognize that they feel open and welcome toward this type of intervention and the team is willing to continue working to integrate new proposals that contribute to excellence in integral, family-centred care. This idea is picked up by the following nurse: "At least, in this unit, there is an immense desire to improve things and learn, you know? So, I think that, once people are given the tools to know how to do things and not create confusion in certain situations… and as long as the infrastructure is also in place… I mean, at the professional level, I think there are never limits here” (COD_09).

The findings reveal that the reality of PICU visits for children depends in great measure on the proactivity of the families and their active participation, indicating that it is mainly the parents who identify the need and make the proposal for the child visit. Along the same lines, Knutsson and Bergbom27 note that it is primarily the parents or legal guardians of the children, and not the members of the care team, who initiate the PICU visit proposal. In contrast, Lanini et al. 28 propose a possible dynamic of PICU visitation for children based on demand.

Taking this “demand-based visit” as a reference, attention must be paid to what we mean by ‘demand’ and ‘need’. According to Jeffers et al.,29 we can define ‘demand’ as the care that users should receive or consume based on their subjective perception of their health needs. In contrast, ‘need’ would be understood as care professionals making decisions based on what is interpreted as a health problem (medical diagnosis) or a human response (nursing diagnosis) to a health-illness problem. This causes us reflect on the need to anticipate the demand by carrying out a systematic assessment of the family to identify risk factors or manifestations of possible problems derived from the hospitalization of the critically-ill child. As mentioned by do Vale et al.,30 nurses should be trained to evaluate the family from an integral perspective, creating spaces to discuss perceptions, concerns, and feelings with parents, thereby identifying problems and planning interventions in a consensual manner.

As for preparing the children for the visit and although the nurses’ statements indicate that the ideal situation is for the parents to inform and prepare the child to visit the PICU, this does not mean that this intervention should be conducted unassisted. It would be part of the role of the care team to support the parents by providing them with all the necessary resources. As Lanini et al.28 point out, the visit requires that the family, the environment, and the care team all be prepared. It is necessary to work with the parents to provide them with guidelines on how and what to tell the child about for their visit to the PICU. On the other hand, according to Mazurek Melnyk et al.,31 the family’s psychological preparedness is enormously important. Thus, to the extent that the parents’ coping resources are enhanced, the children’s intrapersonal and interpersonal resources will be enriched. This preparation, despite being led by the nursing staff, should be approached from an interdisciplinary and collaborative perspective. The nurses’ reports refer to the need to integrate psychologists into the team to provide counselling to families and reinforce their work at the bedside. The latter is also suggested by other authors, such as Haines et al.,32 who point out the need for a collaborative approach to identify and respond to family needs by encouraging the nursing team to communicate proactively with psychologists, social workers, or religious services. As well as developing and implementing consensual protocols to support children and their families during PICU hospitalization [sic].

During the assistance phase, the findings invite us to reflect on the notion of creating welcoming spaces, relational spaces that facilitate communication and interaction among the members of the family unit. Clarke CM.33 points out the relevant work of the nurse in transforming “white” spaces into spaces of proximity and welcome, “colourful” and warm spaces to accommodate children and their families. Knutsson and Bergbom27 add that nurses should use their senses and sensitivity to create authentic places and “meeting spaces”. These meeting spaces would themselves be constituted by elements providing emotional and structural support. With respect to the latter, the nurses admit certain limitations and lack of resources to be able to provide quality emotional support. They also feel that they are not sufficiently prepared in communication and support skills. This idea of a feeling of incompetence is also reflected in other studies, in particular as it relates to the accompaniment and support of children facing situations that entail the loss of a loved one, bereavement, or separation.27

Finally, in relation to consensual decision making, the findings place us in a shared, collaborative decision-making process that allows patients, family, and clinicians to make decisions jointly, taking into consideration the best evidence available and the objectives, values, and preferences of the care unit.34 While this context-based decision making is congruent with a family-centred approach to care, the literature invites us to reflect on the elements that help and those that hinder its implementation.35 Some of the facilitating elements identified in the findings are the therapeutic relationship established with the families, the intrapersonal resources of the families, and the level of knowledge of the health-illness situations on the part of the families. On the other hand, the absence of protocols and the lack of knowledge resources on the part of the professionals to support this decision making would comprise an obstacle.

As limitations of the study, the infrequency with which the nurses have been faced with facilitating child visitation should be pointed out, although they report that these rare experiences have had a great impact on their clinical and personal journey. With respect to the consequences of child visitation on families, their statements are superficial, which means that a wide-sweeping assessment has been unexplored. On the other hand, the intentional sampling for convenience may have limited the possibility of accessing highly valuable experiences and interpretations of the experience.

Inasmuch as the discussion of the findings is concern and taking the limitations of the present study into consideration, the following recommendations for clinical practice are suggested:

- ˗

A systematic assessment of the characteristics and experience of each family with respect to PICU hospitalization is necessary to identify specific needs that may justify the relevance of complex support interventions, such as child visits to the PICU.

- ˗

Parents are the best positioned to prepare their children for a visit to the PICU. Emotional support and support programs can aid in empowering parents and bolstering their sense of control, safety, and comfort in accompanying their child during the intervention.

- ˗

The care team should develop resources and strategies to facilitate the parents’ role as [their children’s] educators and companions in the experience of visiting their critically-ill sibling in the PICU through materials such as brochures, stories, video-tours, or games.

- ˗

The planning of the child’s visit to the PICU should be personalized, addressing the specific needs of each family and child. However, a structured proposal would help in decision making and the provision of support resources for its implementation.

- ˗

The architectural design and structural resources of the PICU should be reconsidered so as to be able to respond to this idea of creating spaces of intimacy and privacy that families demand.

- ˗

An interdisciplinary team is needed that is prepared to look after the psycho-socio-emotional needs of families, as well as the development of spaces for shared reflection to address difficulties in managing communication and relational skills.

- ˗

As for future lines of research with respect to the limitations, we propose that the experience of clinicians who have gone through this should be contrasted with the experience of expert families for the future design of a structured intervention and its subsequent implementation and evaluation. The active involvement of families is both a challenge and a responsibility that is supported by acknowledging users as experts, in that the only way to approach quality care that guarantees a satisfactory experience is through dialogue. In this regard, we are committed to a transformational relationship,32 in which the objective is to work on identifying care needs, planning resources for intervention, and on executing care activities from the perspective of a therapeutic community.

- ˗

Furthermore, delving deeper into experiences of bereavement support is needed, especially in the context of saying goodbye to children who are in an end-of-life situation, in order to provide spaces and opportunities to work on grief and honour the child.36

The experiences of facilitating children’s visits to the PICU typically respond to the demand of families experiencing prolonged hospitalizations or end-of-life situations [of a child]. Nurses receive these proposals favourably and mobilize resources to respond to the demand, which is generally well-received by the treatment team.

The nurses explain that their role in facilitating a child’s visit to the PICU is primarily as support role, acknowledging that the parents do the priority work of preparing their children for the visit. They describe this support as: providing information, welcoming, emotional support, creating spaces for privacy, and monitoring and evaluating how the visit transpires.

Despite the fact that they perceive that their experiences in facilitating child visitation have been very positive and enriching, they acknowledge that they feel insecure and that they lack resources. They consider that having protocols for the intervention as a reference would make decision making easier. However, they recognize that the greatest limitation is in managing therapeutic communication and in providing solid emotional support.

FundingThis work was awarded the 2nd Edition of the Nursing Research Scholarship of the Gregorio Marañón University Hospital (21 November 2018).

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

To all those nurses who, convinced of the need to care from a family-centred approach, have on occasion facilitated the visit of children to the PICU.

To all the care professionals who every day make and contribute to making the hospitalization experience in Pediatric Intensive Care Units kinder, more humane, more comprehensive, and safer.

Please cite this article as: González-Gil MT, Alcolea-Cosín MT, Pérez-García S, Luna-Castaño P, Torrent-Vela S, Piqueras-Rodríguez P, et al. La visita infantil a la unidad de cuidados intensivos pediátricos desde la experiencia de las enfermeras. Enferm Intensiva. 2021;32:133–144.