To analyse the influence of psychotropic substance use on the level of pain in patients with severe trauma.

DesignLongitudinal analytical study.

ScopeIntensive Care Unit (ICU) of Trauma and Emergencies.

PatientsSevere trauma, non-communicative and mechanical ventilation >48h. Two groups of patients were created: users and non-users of psychotropic substances according to medical records.

InterventionsMeasurement of pain level at baseline and during mobilisation, using the Pain Indicator Behaviour Scale.

VariablesDemographic characteristics, pain score, sedation level and type and dose of analgesia and sedation.

ResultsSample of 84 patients, 42 in each group. The pain level in both groups, during mobilisation, showed significant differences p=0.011, with a mean of 3.11 (2.40) for the user group and 1.83 (2.14) for the non-user group. A relative risk of 2.5 CI (1014–6163) was found to have moderate/severe pain in the user group compared to the non-user group. The mean dose of analgesia and continuous sedation was significantly higher in the user group: p=.032 and p=.004 respectively. There was no difference in bolus dose of analgesia and sedation with p=.624 and p=.690 respectively.

ConclusionsPatients with a history of consumption of psychoactive substances show higher levels of pain and experience a higher risk of this being moderate/severe compared to non-users despite receiving higher doses of analgesia and sedation infusion. Key words: pain, multiple trauma, drug users.

Analizar la influencia del consumo de sustancias psicótropas en el nivel de dolor de los pacientes con traumatismo grave.

DiseñoEstudio analítico longitudinal.

ÁmbitoUnidad de Cuidados Intensivos (UCI) de Traumatismos y Emergencias.

PacientesTraumatismo grave, no comunicativo y ventilación mecánica > 48 h. Se crearon 2 grupos de pacientes: consumidores de sustancias psicótropas y no consumidores según historia clínica.

IntervencionesMedición del nivel de dolor en situación basal y durante la movilización, mediante la escala de conductas indicadoras de dolor.

VariablesCaracterísticas demográficas, puntuación de dolor, nivel de sedación y tipo y dosis de analgesia y sedación.

ResultadosMuestra de 84 pacientes, correspondiendo 42 a cada grupo. El nivel de dolor en ambos grupos, durante la movilización, muestra diferencias significativas p=0,011, con una media de 3,11(2,40) para el grupo de consumidores y 1,83(2,14) para el grupo de no consumidores. Se objetiva un riesgo relativo (RR) de 2,5, IC (1,014–6,163) de tener dolor moderado/grave en el grupo de consumidores respecto al de no consumidores. La dosis media de analgesia y sedación continua es significativamente mayor en el grupo de consumidores: p=0,032 y p=0,004, respectivamente. No hay diferencia en la dosis de bolos de analgesia y sedación con p=0,624 y p=0,690, respectivamente.

ConclusionesLos pacientes con antecedentes de consumo de sustancias psicótropas muestran mayor nivel de dolor y tienen más riesgo de que este sea moderado/grave respecto a los no consumidores, a pesar de recibir mayor dosis de analgesia y sedación continua.

Pain is a common symptom in patients admitted to intensive care units (ICU). Various factors are involved in the origin of pain, including the baseline disease itself and the procedures performed on the patient.

What does this article contribute?A history of substance abuse is an important factor to take into account when adjusting the dosage of analgesics and sedation, to ensure the patient's wellbeing during their admission to the ICU.

Implications of the studyPatients with a mental disorder who have consumed psychotropic substances and have been admitted to ICU will benefit in clinical practice from stricter pain monitoring and by adapting their analgesic and sedation doses using protocols that are specific to these types of patients.

The incidence of mental disorders in intensive care units (ICU) is little established and its effect on critical disease or the need for specific care is not well known.1 The use and/or abuse of psychoactive substances is a mental disorder that can result in addiction, dependence and tolerance.2 This condition poses a difficult challenge for safe and successful pain, agitation and delirium management in critical patients. On the one hand, these patients are physically dependent, due to forced abstinence, sudden discontinuation or rapid reduction of doses, combined on the other hand with the phenomena of tolerating or adapting to drugs they are given from the same family as those they consume; opiates and benzodiazepines in particular. In addition, possible interactions with other drugs or medications must also be taken into consideration, if consumption has been recent.3,4

Road traffic accidents are the most common aetiology of trauma; they are for the most part linked to human behaviour, and the consumption of substances that alter behaviour constitutes a risk factor for trauma of all types.5 A great many serious trauma cases caused by road traffic accidents involve the consumption of one or more psychoactive substances, such as alcohol or drugs.5,6 The national serious trauma registry RETRAUCI7 highlights that in up to 27.9% of cases it is clinically suspected or confirmed by analytical tests, focussing primarily on acute consumption. Authors such as Suchyta et al.8 have researched substance dependence, from a chronic perspective, and also highlight their association with trauma.

Furthermore, pain commonly develops in ICU; it can be baseline, caused by the patient's situation, and can occur when care procedures are carried out.9 It has negative implications for the patient's outcome.10–12 The current clinical practice guidelines on the management of pain, agitation and delirium in critical patients13,14 suggest different strategies for assessment, treatment and prevention but they do not cover substance abuse as a possible aetiological or risk factor for greater levels of pain.15

Therefore, the objective of this research study was to analyse the influence of psychotropic substance consumption on pain levels, comparing the pain levels of serious trauma patients who were users of psychotropic drugs with those of serious trauma patients who were not, according to the diagnosis in their clinical histories.

Patients and methodDesignA longitudinal analytical study. The serious trauma patients were followed-up taking substance consumption as the independent variable to define the groups, according to the patients’ clinical histories; the variable dependent was their pain level in 2 situations: baseline and during a painful procedure, mobilisation.9,16 The groups were defined as group i (psychotropic substance consumers) and group ii (non psychotropic drug consumers). The study was approved by the ethics and research committee of the 12 de Octubre University Hospital and the patient's family members signed their informed consent for their inclusion in the study.

ScopeThe study was performed in the ICU of the emergency and trauma department of the 12 de Octubre University Hospital, from January 2014 to November 2015.

Sample subjectsThe sample size was determined based on the mean and standard deviation of the level of pain experienced by non-communicative, serious trauma patients, taking the results obtained in the study by Lopez Lopez et al.17 as the benchmark, with a mean and standard deviation of pain during mobilisation of 3 (2.8). With a 95% confidence level, 80% power, a mean difference of 2 and a ratio between samples of 1, a minimum of 42 patients were studied in each cohort.

The patients were recruited consecutively provided they met all the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria.

- 1.

Inclusion criteria:

- –

Age≥18 years.

- –

Serious trauma, defined as an Injury Severity Score (ISS)≥16.18

- –

Invasive mechanical ventilation in the first 48h.

- –

Non-communicative, defined as being without the use of verbal or motor communication.

- –

- 2.

Exclusion criteria:

- a.

Barbiturate coma.

- b.

Muscle relaxant infusion or after a period of between 1 and 2h after the administration of an isolated dose.

- c.

Tetraplegia.

- a.

- 1.

Demographic variables:

- –

Age and sex.

- –

Cause of trauma: road traffic accident, fall, sports accident, accident at work.

- –

Anatomical region affected: skull, chest, orthopaedic, abdominal, spinal, pelvic and facial.

- –

- 2.

Clinical data:

- a.

Pain level measured by the behavioural indicators of pain scale (ESCID).19

- b.

Level of sedation measured by the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS).20

- c.

Level of consciousness measured by the Coma Scale (GCS).21

- d.

Analgesia and sedative medication: continuous infusion (mg/24h) and isolated doses (mg or μg) administrated for up to a maximum of 8h before measurement.

- e.

History of chronic psychotropic substance use/abuse according to clinical record.

- a.

Prior to assessing the pain levels, the patient's analgesia and/or sedation dose was recorded, either administered continuously or as a bolus, and the level of sedation was assessed using the RASS scale.

The pain measurements were only performed once per subject in the first 48h following admission by an independent observer at 2 different times: baseline and during mobilisation. The observer did not take part in the procedure. The patient's behaviour was observed first and then recorded.

The pain was assessed using the validated tool ESCID, which comprises 5 items: facial expression, calmness, muscle tone, compliance with mechanical ventilation and consolability, scores are awarded ranging from 0 to 2 for each item, so that the total score ranges from 0 to 10. The ESCID pain level classification was followed: no pain=0; mild/moderate pain=1–3, moderate/severe pain=4–6, and severe pain>6.

InstrumentsThe patient's clinical history, to obtain their demographic data, personal background, sedative and analgesic medication administered.

Direct observation, to measure pain using the ESCID scale and to evaluate sedation using the RASS scale.

Statistical analysisDescriptive analysis of the variables, using the mean and standard deviation (SD) for the quantitative variables, and absolute and relative frequencies for the qualitative variables. The comparison of means from the total ESCID score, sedative and analgesic doses were performed using the Student's t-test for independent samples, and the association with the RR of presenting moderate/severe pain according to the group, using the χ2 test. To perform this calculation, the pain variable was categorised as dichotomous, differentiating between mild pain (ESCID≤3) and moderate/severe pain (ESCID>3).

The variables were analysed using IBM® Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS®) 22.

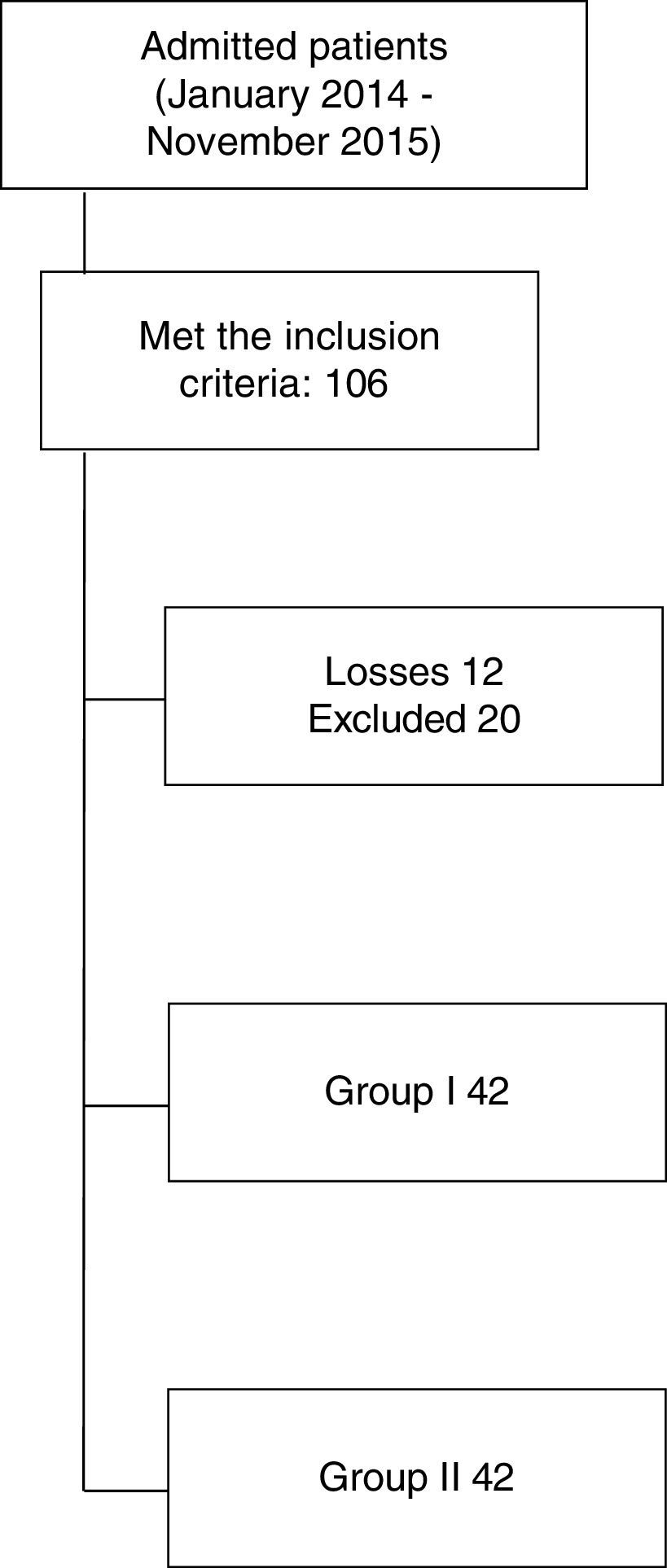

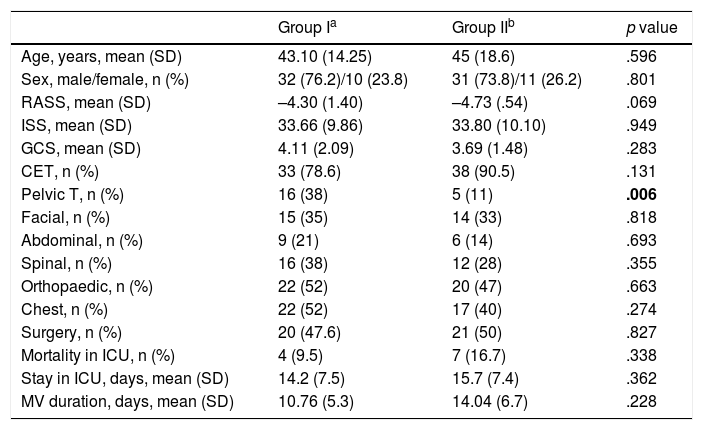

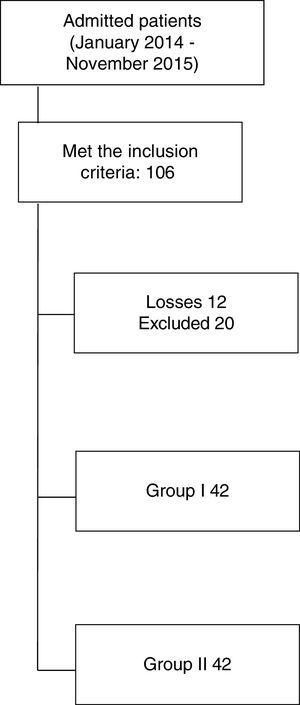

ResultsThe final sample comprised 84 patients, 42 in each group; Fig. 1 shows the flow of patients. The general characteristics of the sample shown in Table 1 reflect that there are no differences in either group of patients, except for the distribution of pelvic trauma. The combination of 2 or more injuries is noteworthy, the main being skull trauma, chest trauma and orthopaedic trauma.

General characteristics of the groups.

| Group Ia | Group IIb | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 43.10 (14.25) | 45 (18.6) | .596 |

| Sex, male/female, n (%) | 32 (76.2)/10 (23.8) | 31 (73.8)/11 (26.2) | .801 |

| RASS, mean (SD) | –4.30 (1.40) | –4.73 (.54) | .069 |

| ISS, mean (SD) | 33.66 (9.86) | 33.80 (10.10) | .949 |

| GCS, mean (SD) | 4.11 (2.09) | 3.69 (1.48) | .283 |

| CET, n (%) | 33 (78.6) | 38 (90.5) | .131 |

| Pelvic T, n (%) | 16 (38) | 5 (11) | .006 |

| Facial, n (%) | 15 (35) | 14 (33) | .818 |

| Abdominal, n (%) | 9 (21) | 6 (14) | .693 |

| Spinal, n (%) | 16 (38) | 12 (28) | .355 |

| Orthopaedic, n (%) | 22 (52) | 20 (47) | .663 |

| Chest, n (%) | 22 (52) | 17 (40) | .274 |

| Surgery, n (%) | 20 (47.6) | 21 (50) | .827 |

| Mortality in ICU, n (%) | 4 (9.5) | 7 (16.7) | .338 |

| Stay in ICU, days, mean (SD) | 14.2 (7.5) | 15.7 (7.4) | .362 |

| MV duration, days, mean (SD) | 10.76 (5.3) | 14.04 (6.7) | .228 |

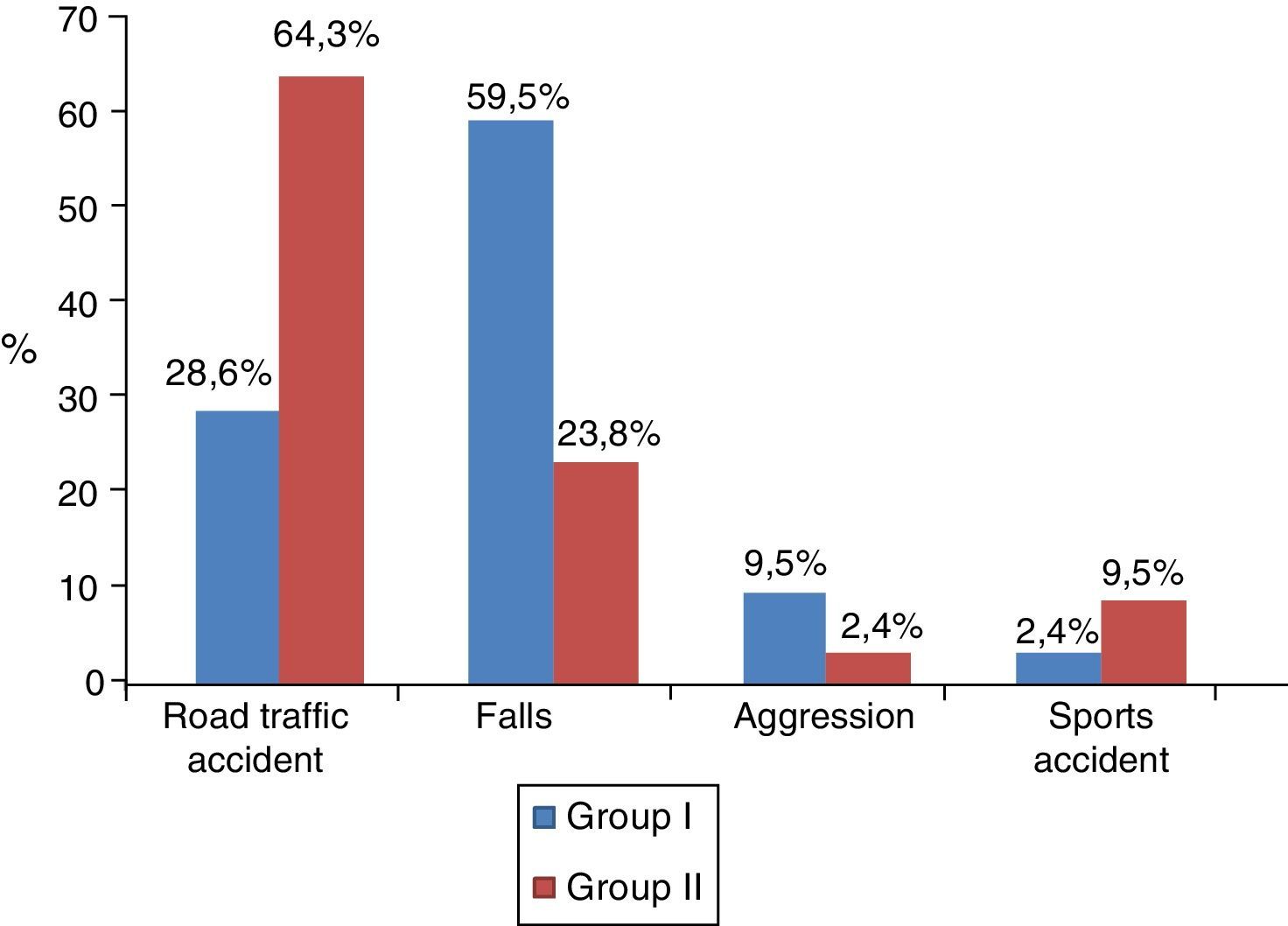

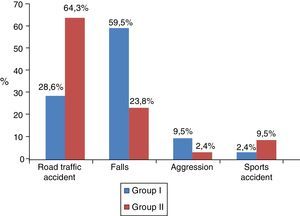

Fig. 2 shows the mechanism of injury of both groups.

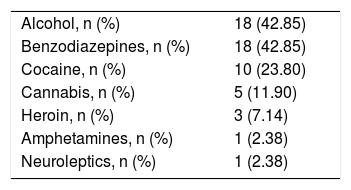

The type of psychotropic substances consumed by the patients (group i) is shown in Table 2. Forty-five point two percent of the patients were consuming more than one substance.

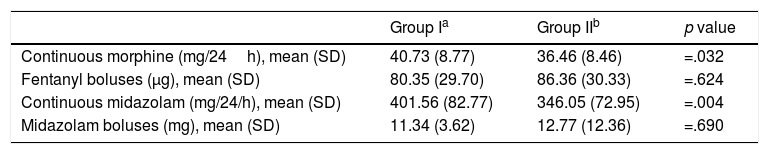

The therapeutic regimen of sedation and analgesia is given in Table 3.

Analgesia and sedation.

| Group Ia | Group IIb | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous morphine (mg/24h), mean (SD) | 40.73 (8.77) | 36.46 (8.46) | =.032 |

| Fentanyl boluses (μg), mean (SD) | 80.35 (29.70) | 86.36 (30.33) | =.624 |

| Continuous midazolam (mg/24/h), mean (SD) | 401.56 (82.77) | 346.05 (72.95) | =.004 |

| Midazolam boluses (mg), mean (SD) | 11.34 (3.62) | 12.77 (12.36) | =.690 |

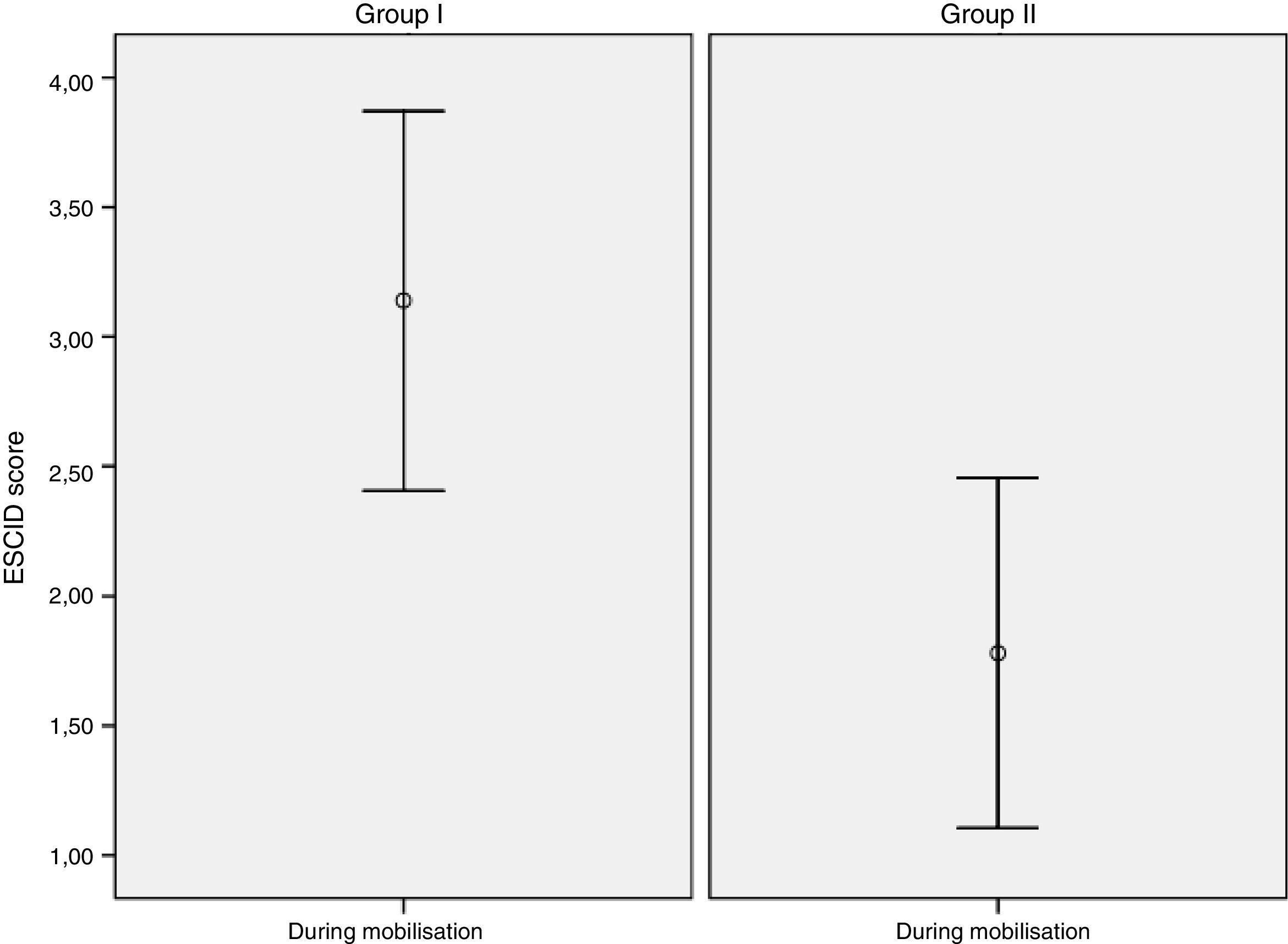

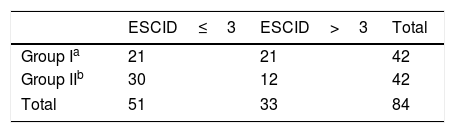

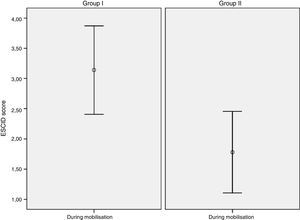

In terms of baseline pain assessment: it was observed in group i that 39 (92.9%) patients had no pain (ESCID=0) and 3 (7.1%) showed mild pain (ESCID=1–3). In group ii, 41 (97.6%) had no pain (ESCID=0) and 1 (2.4%) had moderate-severe pain (ESCID>3). During mobilisation: group i had no pain (ESCID=0) 12 (28.6%), 9 (21.5%) had mild pain (ESCID=1–3) and 21 (50%) had moderate-severe pain (ESCID>3). In group ii, 19 (45.2%) patients had an ESCID score=0, 11 (26.2%) had an ESCID score=1–3 and 12 (28.6%) an ESCID score>3. There were no differences in baseline pain score between either group: group i 0.14 (.56), CI (−.03 to .31) vs group ii .09 (.62), CI (−.09 to .28), with a p value=.713 CI (−.304 to .209). During the painful procedure significant differences were observed in the pain levels of each group: Group I 3.11 (2.4) CI [2.37–3.86) vs group ii 1.83 (2.14) CI (1.16–2.50); p=.011, CI (−2.27 to .29). Fig. 3 shows the mean pain score in both groups during mobilisation.

Table 4 shows the distribution of patients with mild pain (ESCID≤3) and moderate-severe pain (ESCID>3) in both groups during the painful procedure. The patients who were users of psychotropic substances had a greater risk of moderate-severe pain compared to the group who were not, RR 2.5, CI (1.01–6.16).

DiscussionThe epidemiological characteristics of the sample coincide with the typical distribution of trauma in our area, affecting young men in the majority, road accidents and falls being the most frequent causative mechanisms and head injuries the most common anatomical region.7,22,23

The study groups were comparable. However, the distribution of the mechanism of injury showed some peculiarities, falls were more common in group i and road traffic accidents in group ii. With regard to this finding, an association is found in the literature between substance use, mental disorders and falls and intentionality (autolytic ideation).24 This might also explain the different distribution of the pelvic trauma, which predominated in group i.

Alcohol is the most highly consumed substance according to the data published in the survey on alcohol and drugs in Spain25 and those of the European DRUID6 project, although practically 50% of patients consume more than one substance, as can be seen in our series and in the results of other authors, such as Ruiz-García et al.26 and Ruiz et al.,27 from studies on trauma and postoperative patients. A similar distribution is found for patients with medical pathologies such as the series by Wit et al.28 In our study, the consumption of benzodiazepines is noteworthy as well, which was also reported by Walsh et al.29 as a substance that is frequently involved in trauma.

With regard to the assessment of pain, at baseline the patients in both groups either had no pain or mild pain in a minority of cases; however, during the painful procedure there was an increase in the ESCID score, with differences between the groups. The increase was significantly higher in group i than in group ii, despite the fact that they had received higher baseline doses of analgesia and sedation. This is probably associated with the development of hyperalgesia phenomena, tolerance and abstinence syndrome, thus increasing the experience of pain and reducing the response to the treatment given.30–33 Furthermore, the lack of an analgesic protocol prior to the procedure to adapt doses to the patients’ condition before mobilisation might also explain the difference in the pain levels in both groups. The studies by Ruiz et al.27 and Ruiz-García et al.26 found no differences in the baseline administration of analgesia and sedation between users and non-users.

Another aspect that should be highlighted is that, although larger doses of analgesia and sedation were administered in the consumer group, these patients did not have longer mechanical ventilation or stay in the ICU. The study by Wit et al.28 found that consumers required more days on mechanical ventilation.

Taking into account the recommendations by the American Society for Pain Management Nursing (ASPMN)34 and the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP)35 for pain management in substance abuse patients, and the results of this research study, we suggest future lines of study, such as monitoring of the chronic consumption of psychotropic substances before starting long-term treatment, with the objective of identifying the substance that the patient is consuming and that should be taken into account to adapt analgesia and sedation doses, particularly when there is a known history of addition. Thus, the wellbeing of the patient will be ensured and interaction or synergy effects with other drugs will be prevented. Adjusting analgesia should be accompanied by stricter pain monitoring36,37 in this group of patients.

This study has some limitations. On the one hand, the difficulty in identifying patients as psychotropic substance users, which does not always appear in their clinical records, possibly because of fear on the part of the patient or their family of potential stigma that might affect their care. These patients often consume more than one substance, which makes it difficult to stratify the results per type of substance consumed. Moreover, the clinical situation of the serious trauma patient makes it difficult to determine their level of addiction. The experience of patient's pain was not explored qualitatively, bearing in mind that the gold standard in pain assessment is pain reported by the patients themselves. Finally, the method was not randomised on the psychotropic substance users: similar doses or adjusted to higher doses, meaning that other designs and a larger number of patients are necessary.

In terms of the limitations of applying the ESCID scale, the patients were given deep sedation, part of the sample had a sedation level of -5 measured by the RASS scale, which, according to Latorre Marco et al.19 significantly reduces the internal consistency of the scale. Furthermore, patients with cranioencephalic trauma with low GCS scores predominated, which might alter the behaviour of some behavioural indicators or the expression of different behaviours.38 Finally, as a general limitation of the behaviour-based pain scales, the level of deep sedation and the low level of consciousness might partially abolish some indicators of the assessment items.

ConclusionsThe chronic use of psychotropic substances by the serious trauma patients of the sample was a risk factor for moderate-severe pain during mobilisation, despite having received higher doses of analgesia and continuous sedation, compared to the patients who were not psychotropic substance users.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their centre of work regarding patient data confidentiality.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

To the patients and their families, who so generously agreed to participate in this research in the process of their illness. To all the professionals in the ICU of the emergency and trauma department who collaborated in undertaking this study.

Please cite this article as: López-López C, Arranz-Esteban A, Martinez-Ureta MV, Sánchez-Rascón MC, Morales-Sánchez C, Chico-Fernández M. ¿Influyen los antecedentes de consumo de sustancias psicótropas en el nivel de dolor del paciente con traumatismo grave? Enferm Intensiva. 2018;29:64–71.