Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is the term used to describe damage to the liver caused by medicinal products. Its real incidence is unknown, as it is thought that only a minority of cases are reported. It is estimated to be responsible for 4–10% of jaundice-related hospital admissions.

We present the case of a 78-year-old woman admitted for jaundice. The patient had a previous history of hypertension, grade II mitral and aortic regurgitation, dyslipidaemia, hypothyroidism and recurrent paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. She was on treatment with imidapril, bisoprolol, pravastatin, acenocoumarol, levothyroxine and lansoprazole; and in the last six months, she had started treatment with dronedarone. In the previous two years, her alkaline phosphatase and GGT levels had been elevated, at less than twice the upper limit of normal.

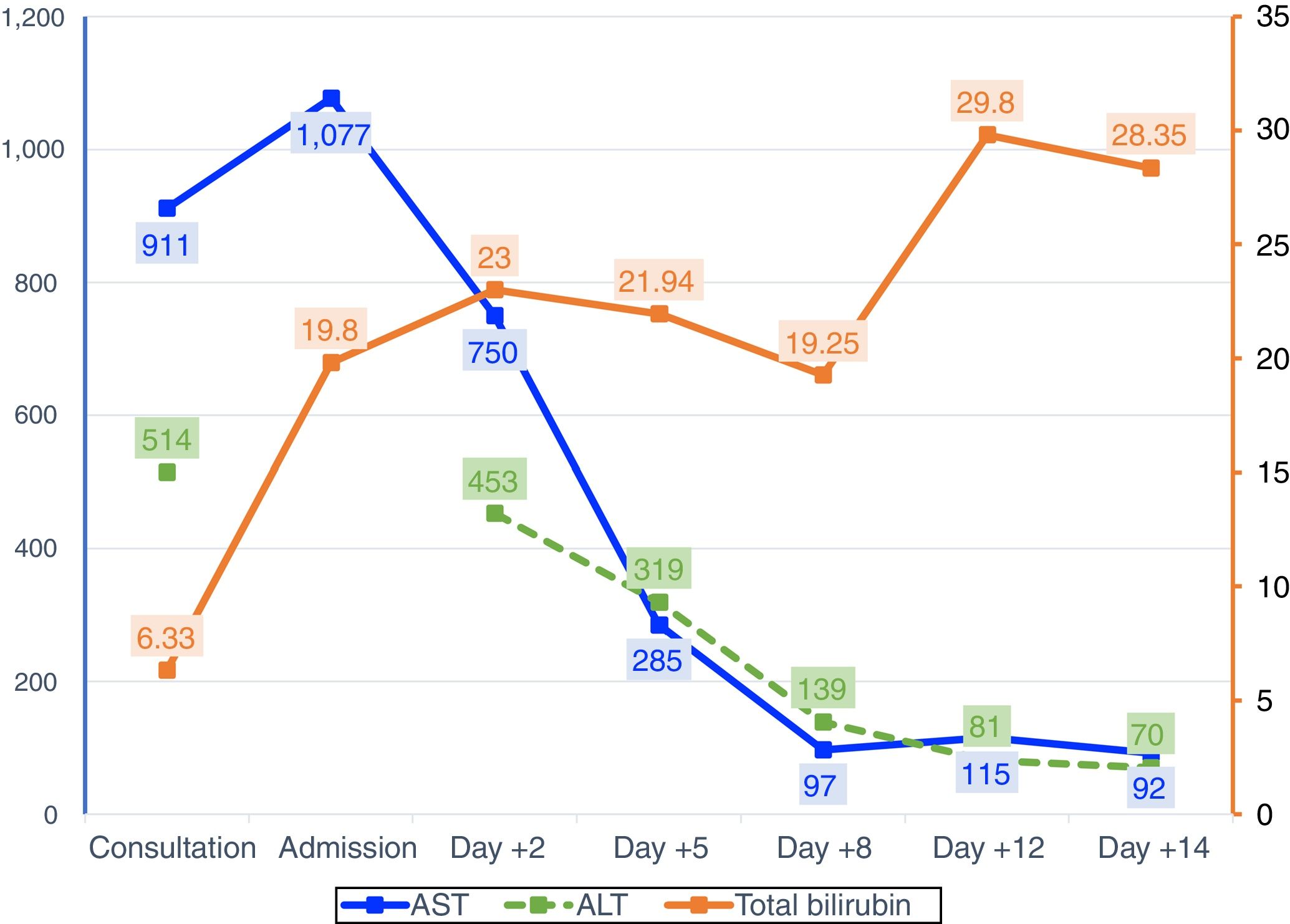

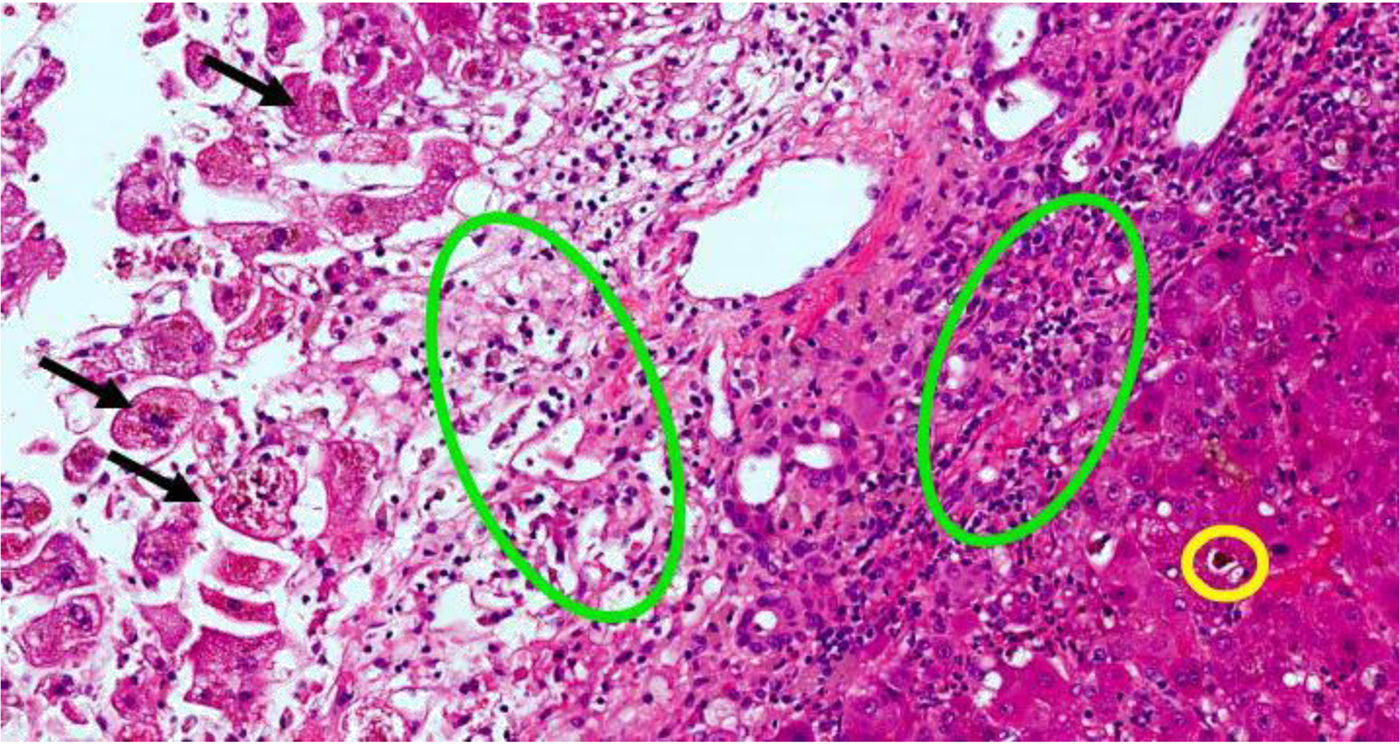

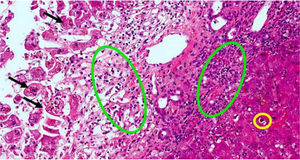

Two weeks prior to admission, she had developed asthenia, anorexia and epigastric pain. The patient attended an appointment at the Gastroenterology Clinic, having previously been referred for diarrhoea, providing blood tests showing elevated transaminases. A week later, after developing jaundice and choluria, without pruritus or fever, she went to Accident and Emergency. Urgent blood tests showed elevation of AST (1284U/l) and total bilirubin (13.6mg/dl). Abdominal ultrasound was normal. Two days after admission, liver function tests showed AST 750U/l, ALT 453U/l and total bilirubin 23mg/dl. The laboratory tests requested in the clinic showed an increase in gamma globulin, demonstrated by IgG levels, elevated ANA (1:320) and positive thyroid peroxidase antibodies; acute viral hepatitis and Wilson's disease were ruled out. On suspicion of autoimmune hepatitis, the patient was started on treatment with corticosteroids. Four days later, there was a slight improvement in bilirubin and transaminases, but she developed grade I encephalopathy and hyponatraemia, which improved with albumin, lactitol and rifaximin. On day ten after admission to hospital, the grade of hepatic encephalopathy worsened, associated with moderate ascites without ultrasound images suggestive of portal hypertension (Fig. 1). Transplant was not considered because of the patient's age. Eighteen days after her admission to hospital, the patient died after an episode of hematemesis. After obtaining the consent of the relatives, a post-mortem liver biopsy was performed, which showed mixed cytolytic and cholestatic hepatitis, suggestive of a toxic/drug aetiology (Fig. 2).

Liver biopsy with hepatitis with mixed cytolytic and cholestatic pattern. Black arrows are necrotic hepatocytes in the centrilobular region. Green circles indicate areas of cholestasis. Yellow circle indicates inflammatory infiltrate of polymorphonuclear cells (neutrophils) and eosinophils. The colours in the image can only be seen in the electronic version of the article.

DILI has varied clinical expression, from asymptomatic forms to acute hepatitis and fulminant hepatic failure. For the diagnosis of DILI caused by dronedarone, we considered the temporal relationship, ruled out other aetiologies, including other concomitant medications,1 and applied the DILI causality scale (Council for International Organisations of Medical Sciences [CIOMS]), which resulted in “possible DILI”. The patient had all the risk factors for DILI-related fulminant hepatic failure: hepatocellular damage, being female, high total bilirubin levels and high AST/ALT ratio.2 Initially, in view of the presence of ANA and hypergammaglobulinaemia, in the differential diagnosis we considered drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis (DIAIH), in which case dronedarone would have acted as a trigger for previously unknown autoimmune liver disease. However, the lack of improvement with corticosteroids and the results of the liver biopsy were compatible with a drug origin associated with autoantibodies, a situation already described in other cases of DILI caused by nitrofurantoin, minocycline, α-methyldopa, hydralazine, diclofenac, statins and some anti-TNFα agents.3 The relationship between DILI and AIH can be very close, with different clinical scenarios which need to be clarified in each individual case.4

Dronedarone is a class III antiarrhythmic indicated for the maintenance of sinus rhythm after effective cardioversion in patients with paroxysmal or persistent atrial fibrillation. It is a non-iodinated benzofuran derivative structurally related to amiodarone. The absence of iodine atoms should minimise adverse effects in non-target organs, such as the thyroid glands. The aim of the addition of the methylsulfonamide group was to reduce lipophilicity, and also, therefore, the neurotoxic potential.5

However, since the authorisation of dronedarone, cases of impaired liver function and hepatocellular damage have been reported throughout the world, leading the European Medicines Agency (EMA) to re-assess dronedarone's risk/benefit ratio and issue new recommendations for use.6 The mechanism of the drug's hepatotoxicity is not yet fully understood. It is probably similar to that of amiodarone, i.e. inhibition of mitochondrial beta-oxidation and dissociation of oxidative phosphorylation, leading to cell damage. The involvement of N-desbutyl-dronedarone, its main metabolite, and its potential cytochrome P1 inhibitor cannot be ruled out either.

In a review of the literature, we found four published cases of DILI caused by dronedarone.7–10 Two of the cases required urgent liver transplant with favourable outcome7,8; both cases developed liver failure five or six months after starting treatment with dronedarone, as in our case. In one case, onset was four days after the start of treatment, with general malaise, nausea, abdominal pain and vomiting, requiring admission to ICU, with a favourable outcome after withdrawal of the drug.9 The fourth case presented as multisystem organ failure, including acute hepatotoxicity, two days after starting the treatment, and despite withdrawing the drug, the liver failure became irreversible and the patient died.10 As atrial fibrillation is a highly prevalent condition and dronedarone is considered as drug of choice, it is essential to emphasise the importance of monitoring liver function. This should be performed before the start of treatment, one week later, monthly for six months, at nine and 12 months, and periodically thereafter.

Please cite this article as: Guzmán Ramos MI, Romero García T, Márquez Saavedra E, Suárez García E, Martínez Castillo R. Daño hepático inducido por dronedarona. Descripción de un caso clínico. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:636–638.