The treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has been revolutionised in recent years and now tends to be mainly outpatient and with less impact on the patient's quality of life. Nevertheless, hospital admissions are still common.1–3

The aim of our study was to analyse the admissions of patients with IBD in a tertiary hospital like ours with an IBD unit.

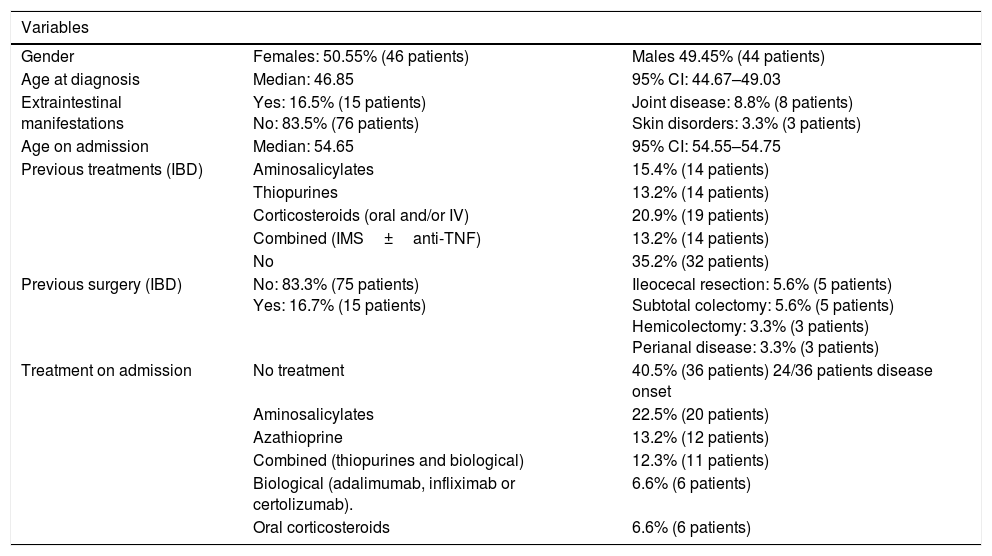

We prospectively included patients with an established diagnosis of IBD (ulcerative colitis [UC], Crohn's disease [CD] or indeterminate colitis [IC]) who were admitted to our hospital, whether at onset or during the course of their disease, from October 2015 to October 2016. A total of 91 patients were identified who required admission because of IBD. The patients’ baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Baseline and disease characteristics.

| Variables | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Females: 50.55% (46 patients) | Males 49.45% (44 patients) |

| Age at diagnosis | Median: 46.85 | 95% CI: 44.67–49.03 |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | Yes: 16.5% (15 patients) No: 83.5% (76 patients) | Joint disease: 8.8% (8 patients) Skin disorders: 3.3% (3 patients) |

| Age on admission | Median: 54.65 | 95% CI: 54.55–54.75 |

| Previous treatments (IBD) | Aminosalicylates | 15.4% (14 patients) |

| Thiopurines | 13.2% (14 patients) | |

| Corticosteroids (oral and/or IV) | 20.9% (19 patients) | |

| Combined (IMS±anti-TNF) | 13.2% (14 patients) | |

| No | 35.2% (32 patients) | |

| Previous surgery (IBD) | No: 83.3% (75 patients) Yes: 16.7% (15 patients) | Ileocecal resection: 5.6% (5 patients) Subtotal colectomy: 5.6% (5 patients) Hemicolectomy: 3.3% (3 patients) Perianal disease: 3.3% (3 patients) |

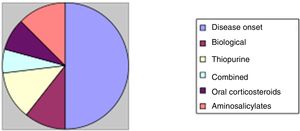

| Treatment on admission | No treatment | 40.5% (36 patients) 24/36 patients disease onset |

| Aminosalicylates | 22.5% (20 patients) | |

| Azathioprine | 13.2% (12 patients) | |

| Combined (thiopurines and biological) | 12.3% (11 patients) | |

| Biological (adalimumab, infliximab or certolizumab). | 6.6% (6 patients) | |

| Oral corticosteroids | 6.6% (6 patients) |

At the time of the analysis, a total of 1260 patients were under active monitoring in our unit, giving a cumulative incidence of 7.2% per year.

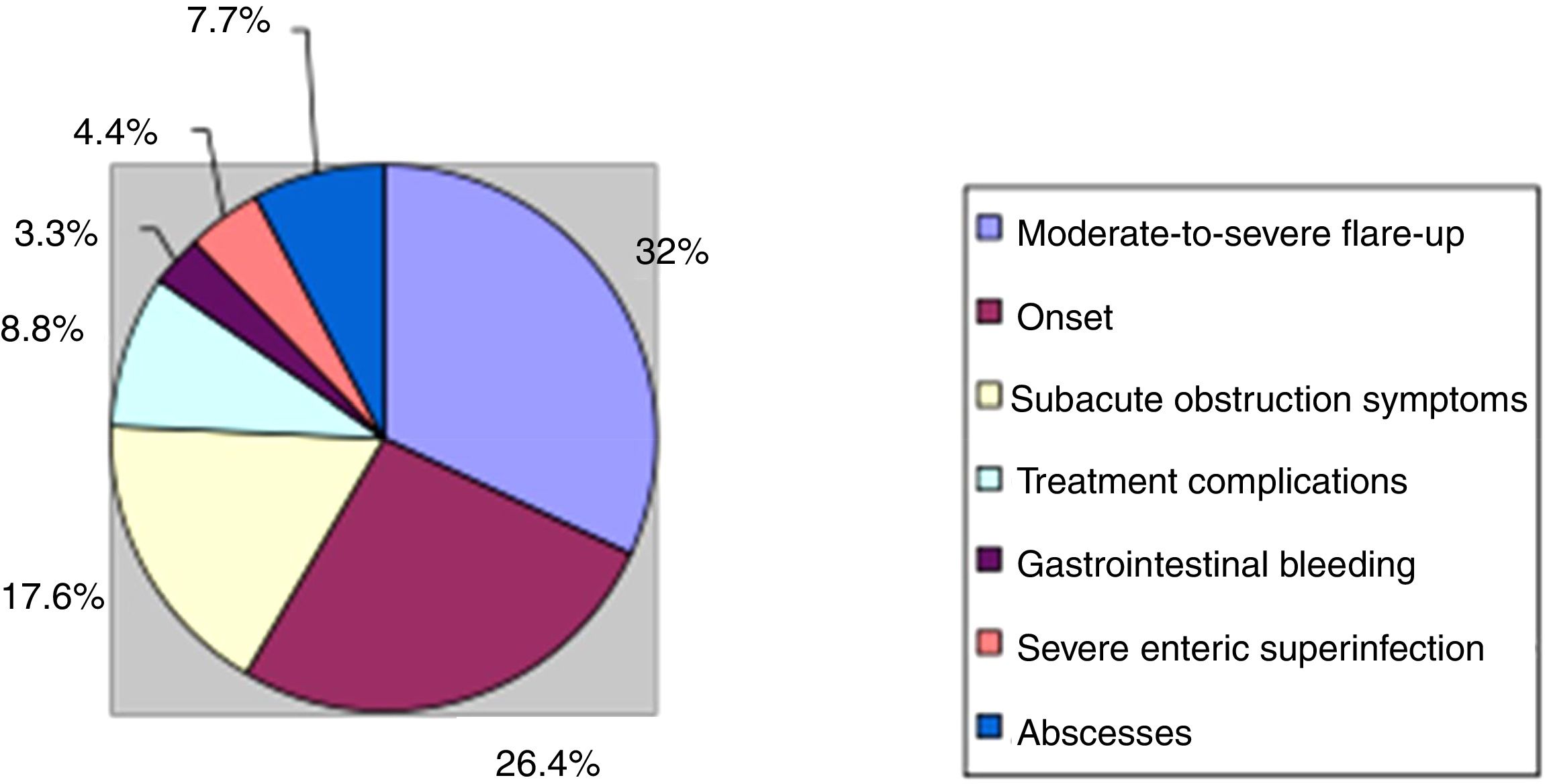

Analysing the reasons for admission during the study period, we found that in the majority of cases (29 patients, 31.8%) the patients had moderate-to-severe flare-ups of the disease which required hospital treatment. Another 24 patients (11 UC and 13 CD, 26.4%) were also admitted because of a flare-up, but in the context of the onset/diagnosis of the disease. The next most common reason for admission was symptoms of subacute obstruction in CD (16 patients, 17.6%) followed by abdominal abscesses, also in CD (7 patients, 7.7%). In six of these patients (6.6%) admission served as a “bridge” for surgical treatment.

We also found that in 8.8% of cases, admission was for the management and/or treatment of complications related to the IBD treatment (four thiopurine-induced acute pancreatitis and one severe azathioprine-induced cholestatic hepatitis, two pneumonias in an immunosuppressed patient and one miliary tuberculosis in the context of biological treatment). In the remaining cases, admissions were for less common causes, which included gastrointestinal bleeding that required haemodynamic and/or transfusion support (3 patients, 3.3%), and development of a serious enteral superinfection (4 patients, 4.4%). The causes are shown in Fig. 1.

Of the 91 patients included, five required re-admission during the study period for IBD-related complications; in three of these cases, their first admission had been prompted by the onset of the disease.

The mean length of stay in hospital was 13.93 days (95% CI: 10.33–17.54). No differences were found in mean length of stay between the patients admitted at onset (mean: 13.48; SD: 5.8) and those diagnosed previously with IBD (mean: 14.13; SD: 20.2); these results were not statistically significant (p=0.87). The mean length of stay was slightly longer for patients with CD, at 15.3 days compared to 12.27 days for UC. However, these results were not statistically significant (p=0.41).

We did find differences in length of stay according to the treatment the patients were taking on admission; mean length of stay was significantly longer for patients on combined treatment (23.09 days) compared to other treatment groups (aminosalicylates 16.6 days, azathioprine 9.63 days, biological 11 days, oral corticosteroids 9.8 days). No differences were found in mean length of stay between patients on no treatment on admission for their IBD (12.3 days) and those on established treatment (p=0.602).

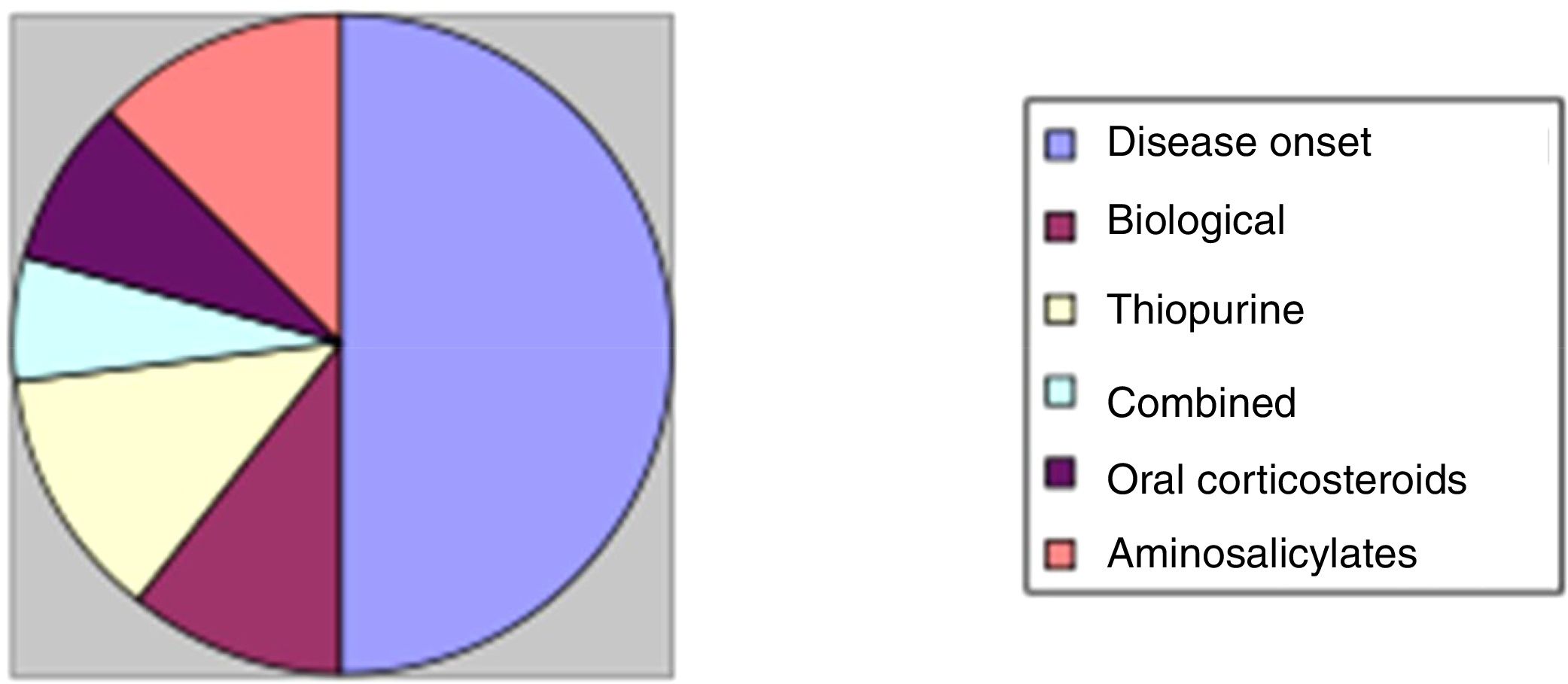

Once in hospital, 50 patients (55%) were treated with intravenous corticosteroids, almost half of whom (24 patients, 48%) had been admitted at disease onset for moderate-to-severe flare-ups. Of the other 26 patients: five (10%) were on biological treatment; six (12%) were on thiopurines; three (6%), combined treatment; and four (8%), oral corticosteroids without complete response. One patient was not taking any treatment on his own initiative. These results are shown in Fig. 2.

In our experience, hospital admissions are still common in IBD despite improvements in follow-up and outpatient treatment. However, in our sample, the admission rate was lower than described in the literature, with a high percentage in the context of onset of the disease.4,5

Please cite this article as: Suarez Ferrer C, Poza Cordon J, Cerpa Arencibia A, Sanchez Azofra M, Martin Arranz E, Jacuotot Herranz M, et al. Hospitalización en enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal: perspectiva actual. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:350–352.