Premalignant gastric lesions have an increased risk to develop gastric cancer.

ObjectiveTo evaluate the usefulness of systematic endoscopy that includes chromoendoscopy with a double dye staining technique for the detection of dysplasia in patients with premalignant gastric lesions.

Patients and methodsThis longitudinal, prospective study was performed in patients with gastric atrophy, intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia who were referred for endoscopy less than 6 months after the initial diagnosis. The second endoscopy was performed in three phases: phase 1, exhaustive and systematic review of the mucosa with photographic documentation and biopsies of suspicious areas; phase 2, chromoendoscopy with a double dye staining technique using acetic acid 1.2% and indigo carmine 0.5%; phase 3, topographic mapping and random biopsies.

ResultsA total of 50 patients were included. Nine (18%) had atrophic gastritis, 38 (76%) had intestinal metaplasia, and 3 (6%) had low-grade dysplasia. Systematic endoscopy with chromoendoscopy using a double dye staining technique detected more patients with dysplasia (9 vs. 3, p<.05), and a larger number of biopsies with the diagnosis of dysplasia were obtained. This occurred for visible (6 vs. 0, p<.05) and non-visible lesions (6 vs. 3, p=NS). In one patient, initial low-grade dysplasia was not detected again in the systematic endoscopy, giving a global endoscopic performance for the detection of lesions of 92%.

ConclusionsPatients with premalignant gastric lesions have synchronous lesions with greater histological severity, which are detected when systematic endoscopy is conducted with indigo carmine dye added to acetic acid.

Las lesiones premalignas gástricas constituyen un factor de riesgo para desarrollar cáncer gástrico.

ObjetivoEvaluar la utilidad de una endoscopia sistemática que incluye bicromoendoscopia para la detección de displasia en pacientes con lesiones premalignas gástricas.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio longitudinal y prospectivo de pacientes consecutivos con diagnóstico de atrofia gástrica, metaplasia intestinal o displasia remitidos para nueva valoración por endoscopia antes de los 6 meses de la endoscopia inicial. La nueva endoscopia se realizó en 3 fases: revisión exhaustiva y sistemática de toda la mucosa con toma de fotos y biopsias de las lesiones sospechosas (fase 1), bicromoendoscopia con una mezcla de ácido acético 1,2% e índigo carmín 0,5% (fase 2) y mapeo topográfico con toma de biopsias aleatorias (fase 3).

ResultadosCincuenta pacientes con diagnóstico de gastritis atrófica (n=9, 18%), metaplasia intestinal (n=38, 76%) y displasia de bajo grado (n=3, 6%). La endoscopia sistemática con bicromoendoscopia identificó más pacientes con displasia (9 versus 3, p<0,05) y se obtuvieron más biopsias con diagnóstico de displasia, tanto en lesiones visibles (6 vs. 0, p<0,05) como no visibles (6 vs. 3, p=NS). En un paciente con displasia de bajo grado inicial, esta no volvió a detectarse en la endoscopia sistemática, siendo el rendimiento global de la endoscopia de seguimiento para detectar lesiones del 92%.

ConclusionesLos pacientes con lesiones premalignas gástricas presentan lesiones sincrónicas de mayor severidad histológica que se ponen de manifiesto al realizar una endoscopia sistemática que incluye el uso de bicromoendoscopia.

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most frequent types of cancer worldwide1 and the second most common cause of cancer-related death in the world, with up to 1 million deaths annually.2 Prognosis is good–a 5-year survival rate of 80%–when diagnosis is made at an early stage (i.e., lesions localized in the mucosa or submucosa).3 It is therefore of utmost importance to endoscopically diagnose GC in the initial phases of the disease.

As a major risk factor for the development of GC, premalignant lesions of the stomach encompass a variety of conditions such as atrophic chronic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia.4 High-grade dysplasia is associated with higher risk (a hazard ratio of 40).5 Recently published guidelines4,6 include recommendations for the diagnosis and surveillance of these lesions. They recommend repeating the diagnostic and staging endoscopy when any of the aforementioned premalignant lesions are found, as well as taking targeted biopsies of visible lesions in order to evaluate their extension and severity, and performing random biopsies (topographic mapping) in order to identify synchronous lesions.4,6 Subsequent endoscopic surveillance is recommended with a frequency varying according to the presence (or absence) of dysplasia and the extent of the atrophy and/or metaplasia.4 The recommendations are based on the fact that low- and high-grade dysplasia can present as endoscopically visible depressed or elevated lesions4 or as flat isolated or multifocal lesions.7–10

Various methods have been shown to improve the detection of endoscopically visible lesions and early GC, such as thorough cleansing of the gastric mucosa with mucolytic solutions,11 meticulous examination of the gastric mucosa12 and dye-based or digital chromoendoscopy.13–17 The European guidelines recommend using the best endoscopic method available, as insufficient data is available to recommend any one in particular.

Chromoendoscopy with indigo carmine is widely used in the stomach–its efficacy having been demonstrated in numerous studies–as indigo carmine deposited on the depressed areas of the mucosa accentuates depressed-type early GC.18 Acetic acid, extensively used in the oesophagus, causes the epithelium to change colour through protein acetylation and denaturation and also has a mucolytic effect.19 Relatively little evidence is available regarding bichromoendoscopy with acetic acid and indigo carmine. Yamashita el al.15 observed that bichromoendoscopy enabled much better visualization of the margins of gastric neoplasms and adenomatous lesions that had not been detected with either conventional endoscopy or chromoendoscopy with indigo carmine alone. Further studies have confirmed these results.16,17,20,21

The aim of our study was to evaluate the usefulness of systematic bichromoendoscopy with acetic acid and indigo carmine for the detection of dysplasia in patients with premalignant gastric lesions.

Patients and methodsIncluded consecutively in our study between March 2014 and August 2014 were all patients diagnosed with gastric atrophy, intestinal metaplasia or low-grade dysplasia who had been referred for a repeat endoscopy within 6 months of the initial endoscopy. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, decompensation of a concomitant disease and refusal to participate in the study. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Lambayeque Regional Hospital (Peru).

The procedures were carried out using a high resolution gastroscope (EG-250 WR5, Fujinon, Tokyo) and EPX 2500 processor (Fujinon, Tokyo). Sedation was superficial, based on intravenous midazolam and a local pharyngeal anaesthetic. Air was used to achieve adequate insufflation. To thoroughly cleanse the gastric mucosa, a mucolytic solution (600mg of acetylcysteine plus 40mg of simethicone diluted in 100mL of water) was administered some 30–60min before the procedure.

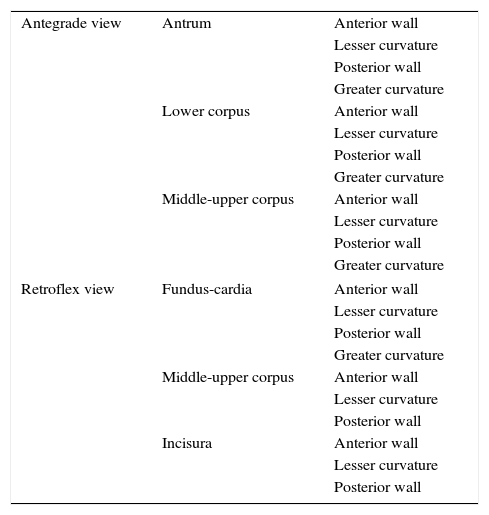

The systematic endoscopy was performed in 3 steps. In step 1, the entire gastric mucosa was thoroughly, systematically and sequentially reviewed using the systematic screening protocol for the stomach proposed by Yao13 (Table 1). Photographs taken were saved to a computer and videos were digitized for subsequent review. Any suspicious lesions were biopsied and the corresponding samples were labelled. Step 2 consisted of the bichromoendoscopy. The gastric mucosa was first sprayed with a 1:1 mixture of 1.2% acetic acid and 0.5% indigo carmine and all air was aspirated to achieve better contact with the gastric mucosa. Air was again insufflated after 2–3min and the remaining solution was aspirated. The gastric mucosa was re-reviewed and biopsies were taken of any suspicious areas. Finally, step 3 consisted of topographic mapping–in accordance with American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommendations6–based on random samples taken from the antrum, incisura and corpus.

Gastric mucosa systematic screening protocol.

| Antegrade view | Antrum | Anterior wall |

| Lesser curvature | ||

| Posterior wall | ||

| Greater curvature | ||

| Lower corpus | Anterior wall | |

| Lesser curvature | ||

| Posterior wall | ||

| Greater curvature | ||

| Middle-upper corpus | Anterior wall | |

| Lesser curvature | ||

| Posterior wall | ||

| Greater curvature | ||

| Retroflex view | Fundus-cardia | Anterior wall |

| Lesser curvature | ||

| Posterior wall | ||

| Greater curvature | ||

| Middle-upper corpus | Anterior wall | |

| Lesser curvature | ||

| Posterior wall | ||

| Incisura | Anterior wall | |

| Lesser curvature | ||

| Posterior wall | ||

The biopsies were evaluated by an expert pathologist and classified according to the operative link on gastritis assessment (OLGA) staging system.22

Statistical analysisContinuous variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation and range. Univariate analysis was performed using the McNemar Chi-square test. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical programme SPSS V.18 was used for the analysis.

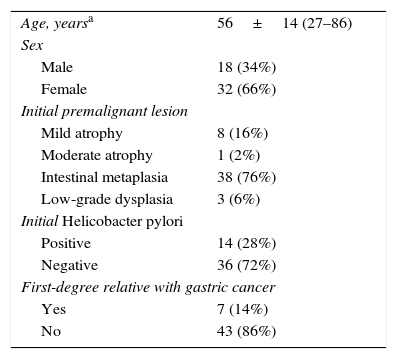

ResultsA total of 50 patients with premalignant gastric lesions were included: 9 with atrophy (18%), 38 with intestinal metaplasia (76%) and 3 with low-grade dysplasia (6%). Most did not have Helicobacter pylori infection or a family history of GC (Table 2). Mean examination time was 23±3.6min (range 15–28min). No patient presented adverse effects.

Epidemiological characteristics of patients with premalignant gastric lesions.

| Age, yearsa | 56±14 (27–86) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 18 (34%) |

| Female | 32 (66%) |

| Initial premalignant lesion | |

| Mild atrophy | 8 (16%) |

| Moderate atrophy | 1 (2%) |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 38 (76%) |

| Low-grade dysplasia | 3 (6%) |

| Initial Helicobacter pylori | |

| Positive | 14 (28%) |

| Negative | 36 (72%) |

| First-degree relative with gastric cancer | |

| Yes | 7 (14%) |

| No | 43 (86%) |

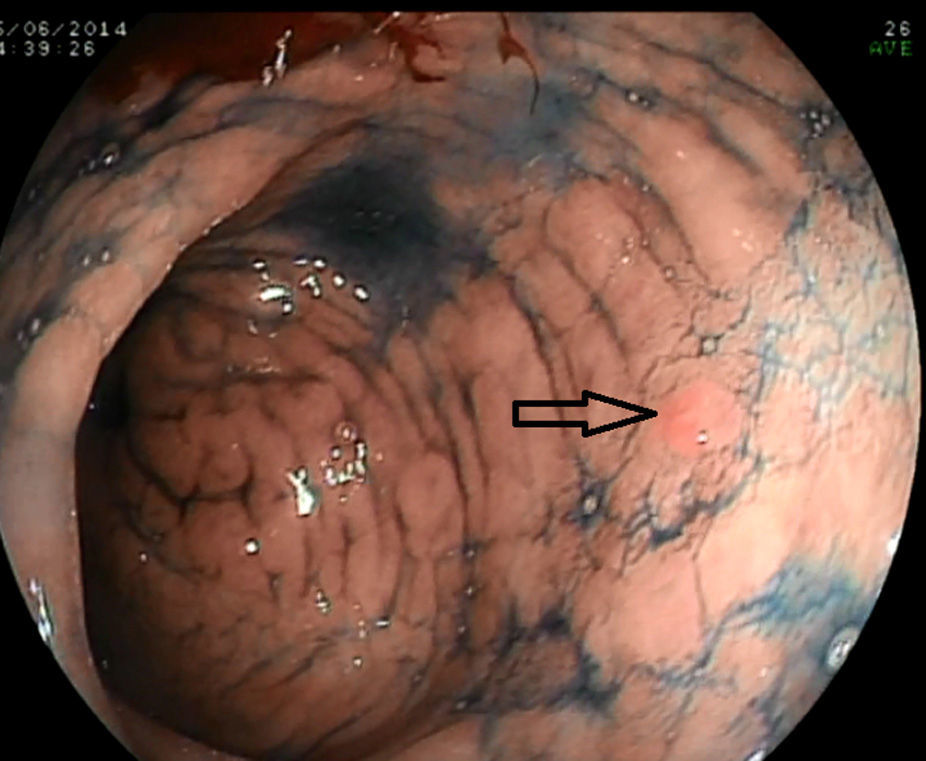

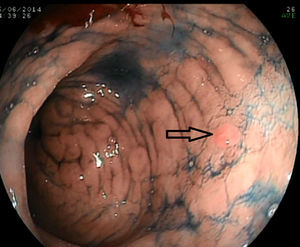

The systematic endoscopy identified 15 visible lesions in steps 1 and 2 for biopsy (Fig. 1) and a total of 150 random biopsies were taken from normal mucosa following the protocol for step 3. Dysplasia (11 low-grade and 1 high-grade) was diagnosed on 12 occasions, but only 6 referred to visible lesions. The results for the 165 biopsies are summarized in Table 3.

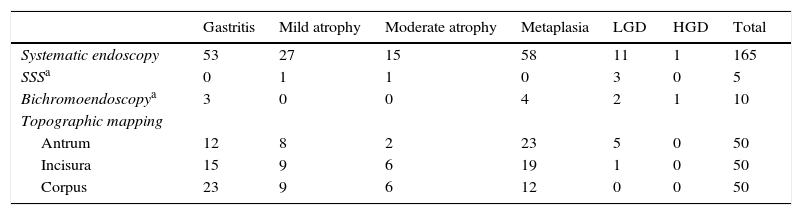

Distribution of premalignant gastric lesions found in the different systematic endoscopy steps.

| Gastritis | Mild atrophy | Moderate atrophy | Metaplasia | LGD | HGD | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic endoscopy | 53 | 27 | 15 | 58 | 11 | 1 | 165 |

| SSSa | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 5 |

| Bichromoendoscopya | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 10 |

| Topographic mapping | |||||||

| Antrum | 12 | 8 | 2 | 23 | 5 | 0 | 50 |

| Incisura | 15 | 9 | 6 | 19 | 1 | 0 | 50 |

| Corpus | 23 | 9 | 6 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 50 |

HGD, high-grade dysplasia; LGD, low-grade dysplasia; SSS, systematic screening of the gastric mucosa.

In the per-patient analysis, 46 had some kind of lesion. Considering only those of greater histological severity, patients had the following lesions: 27 had intestinal metaplasia (54%); 14 had gastric atrophy (28%); 8 had low-grade dysplasia (16%); and 1 had high-grade dysplasia (2%). Seven of the dysplasia lesions were diagnosed in 7 patients with an initial diagnosis of intestinal metaplasia (18.5%). In 4 patients (8%), the systematic endoscopy did not identify any type of lesion (including in 1 patient with previous low-grade dysplasia) (Table 4). Therefore, overall lesion detection by the systematic follow-up endoscopy was 92% (76% in the antrum, 70% in the incisura and 56% in the corpus) for an actual prevalence of dysplasia in this patient series of 20% (10 of 50 patients). Table 5 describes the characteristics of the patients with dysplasia and the macroscopic and histological characteristics of their lesions.

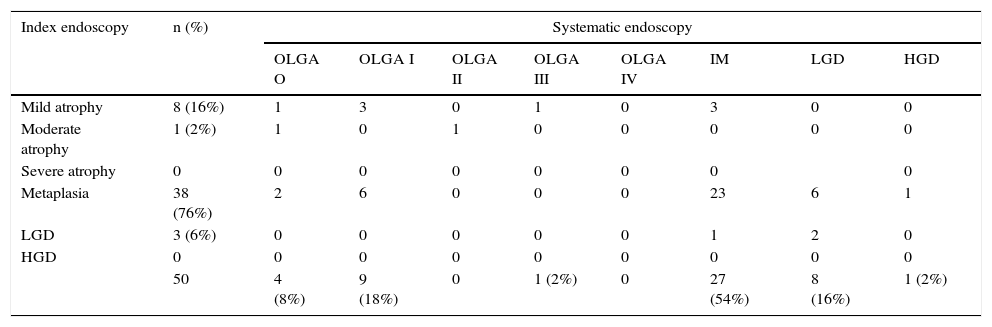

Distribution of premalignant lesions in the systematic endoscopy, considering only histologically more severe lesions in relation to the initial diagnosis.

| Index endoscopy | n (%) | Systematic endoscopy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLGA O | OLGA I | OLGA II | OLGA III | OLGA IV | IM | LGD | HGD | ||

| Mild atrophy | 8 (16%) | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Moderate atrophy | 1 (2%) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Severe atrophy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Metaplasia | 38 (76%) | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 6 | 1 |

| LGD | 3 (6%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| HGD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 50 | 4 (8%) | 9 (18%) | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 | 27 (54%) | 8 (16%) | 1 (2%) | |

HGD, high-grade dysplasia; IM, intestinal metaplasia; LGD, low-grade dysplasia; OLGA, operative link on gastritis assessment.

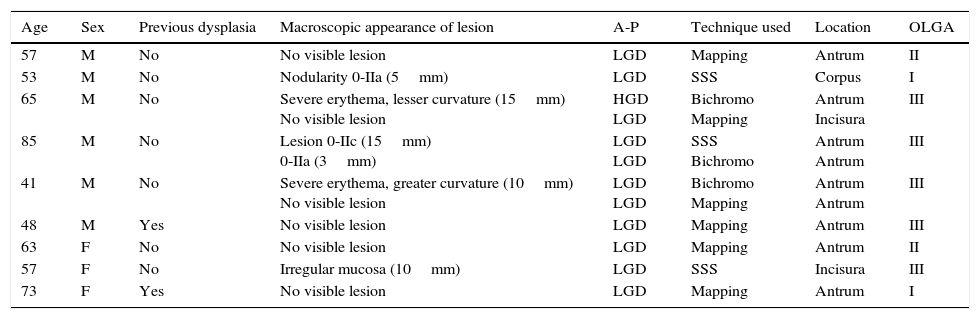

Characteristics of patients with dysplasia and lesions detected in the systematic endoscopy.

| Age | Sex | Previous dysplasia | Macroscopic appearance of lesion | A-P | Technique used | Location | OLGA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 57 | M | No | No visible lesion | LGD | Mapping | Antrum | II |

| 53 | M | No | Nodularity 0-IIa (5mm) | LGD | SSS | Corpus | I |

| 65 | M | No | Severe erythema, lesser curvature (15mm) No visible lesion | HGD LGD | Bichromo Mapping | Antrum Incisura | III |

| 85 | M | No | Lesion 0-IIc (15mm) 0-IIa (3mm) | LGD LGD | SSS Bichromo | Antrum Antrum | III |

| 41 | M | No | Severe erythema, greater curvature (10mm) No visible lesion | LGD LGD | Bichromo Mapping | Antrum Antrum | III |

| 48 | M | Yes | No visible lesion | LGD | Mapping | Antrum | III |

| 63 | F | No | No visible lesion | LGD | Mapping | Antrum | II |

| 57 | F | No | Irregular mucosa (10mm) | LGD | SSS | Incisura | III |

| 73 | F | Yes | No visible lesion | LGD | Mapping | Antrum | I |

HGD, high-grade dysplasia; LGD, low-grade dysplasia; OLGA, operative link on gastritis assessment; SSS, systematic screening of the gastric mucosa.

Overall, the systematic endoscopy identified more patients with dysplasia (9 vs. 3, p<0.05) and diagnosed more visible (6 vs. 0, p<0.05) and more non-visible (6 vs. 3, statistically non-significant) dysplasia lesions.

DiscussionSurveillance of premalignant gastric lesions is important, as these have been identified as a risk factor for the development of GC, with the risk depending on both the severity and extension of the lesions.4,5 The European guidelines4 recommend repeating the diagnostic and staging endoscopy following initial diagnosis of a premalignant gastric lesion, and also recommend using the best available endoscopic method–since there is insufficient data to recommend any method in particular–to detect synchronous premalignant lesions. Our study is the first to demonstrate the usefulness of systematic follow-up endoscopy combined with bichromoendoscopy based on acetic acid and indigo carmine in detecting not only more visible lesions, but also in identifying more patients with dysplasia and obtaining more biopsies with a diagnosis of dysplasia.

Few studies have evaluated a systematic approach based on use of several specific techniques for initial surveillance endoscopy. The usefulness of this approach has been demonstrated by Simone et al.,10 for patients with a histopathological finding of dysplasia and well-differentiated adenocarcinoma without visible lesions. After what the authors called “rescue endoscopy”, consisting of the sequential use of flexible spectral imaging colour enhancement, chromoendoscopy with indigo carmine and magnification, visible lesions were found in 18 of the 20 patients in the study.

No data exist that enable recommendations to be made regarding the ideal interval between the index endoscopy and the initial surveillance endoscopy. A recent study with patients who presented early GC, despite a normal endoscopy in the previous 2 years, showed that early GC was associated with the presence of very subtle intestinal metaplasia lesions, 9 with the authors recommending closer follow-up of patients initially diagnosed with intestinal metaplasia. Our study results corroborate this recommendation, as 7 of the 38 patients (18.5%) with initial intestinal metaplasia in our study were found to have dysplasia by the systematic endoscopy.

In our study, systematic endoscopy with bichromoendoscopy confirmed the diagnosis of a premalignant lesion (metaplasia, atrophy or dysplasia) in 92% of our patients, a figure higher than that reported by other authors using other methods. De Vries et al.23 and Singla et al.24 obtained a diagnostic yield of 75% and 71% using white light and topographic mapping, respectively, while Capelle et al.25 obtained a yield of 83.7% using systematic mapping and narrow-band imaging. The lower percentages reported for these studies are possibly explained by the fact that random sample collection was not performed as thoroughly as recommended in current guidelines; another reason is that the prevalence of GC in their populations (USA and the Netherlands) is lower than in the Peruvian population that makes up our study sample.26,27

A major problem with surveillance endoscopies is that not only do they often fail to confirm previous diagnoses of dysplasia, they also fail to identify new cases.23–25 In our study, although the systematic endoscopy failed to identify 1 of the 3 patients with initial dysplasia, it did diagnose a further 7 patients with dysplasia. In following our systematic endoscopy protocol, bichromoendoscopy alone identified just 3 lesions whereas random biopsies identified 6 areas of dysplasia. These findings would confirm the importance of taking biopsies from different anatomical areas of the stomach.23 Again, however, our study population with a high prevalence of GC could have affected our results.23,27

The variable endoscopic morphology of gastric dysplasia means it can present as visible lesions that are easily identifiable with white light or as lesions that may go unnoticed even with the use of specific techniques.4 Of the lesions in our study, we found that 25% had morphologies that could be classified according to Paris endoscopic classification criteria, 25% presented an abnormality in the mucosa and 50% presented endoscopically as non-specific gastropathy.

The diagnosis of dysplasia lesions is particularly important as it determines the follow-up interval for patients. A follow-up endoscopy is recommended at 3 years for intestinal metaplasia and/or atrophic gastritis, and at between 6 months and 1 year for dysplasia (depending on whether it is high or low grade).4 In our study, the detection of histologically more severe synchronous lesions by systemic endoscopy with bichromoendoscopy led to a change in the follow-up strategy for 14% of our patients. As for a further 42% (21) of our patients, these avoided the need for a follow-up endoscopy, as their mild to moderate gastric atrophy and/or metaplasia was confined to the antrum.4

An important factor in surveillance gastroscopies based on advanced methods is the time investment. Unlike screening colonoscopies,28 no recommendations exist regarding times associated with better examination quality, although 1 study suggested that more than 7min enabled more premalignant lesions to be identified in patients diagnosed with dyspepsia.29 Some scientific societies have proposed that endoscopy in high-risk patients should last 30–45min.30

In conclusion, patients with premalignant gastric lesions typically have histologically more severe synchronous lesions that can be detected with systematic endoscopy and bichromoendoscopy with acetic acid and indigo carmine. Given the practical implications for follow-up intervals for these patients, we would suggest performing systematic endoscopy with bichromoendoscopy within 6 months of an initial diagnosis of a premalignant gastric lesion.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Yep-Gamarra V, Díaz-Vélez C, Araujo I, Ginès À, Fernández-Esparrach G. Utilidad de la endoscopia sistemática con bicromoendoscopia para la detección de displasia en pacientes con lesiones premalignas gástricas. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:49–54.