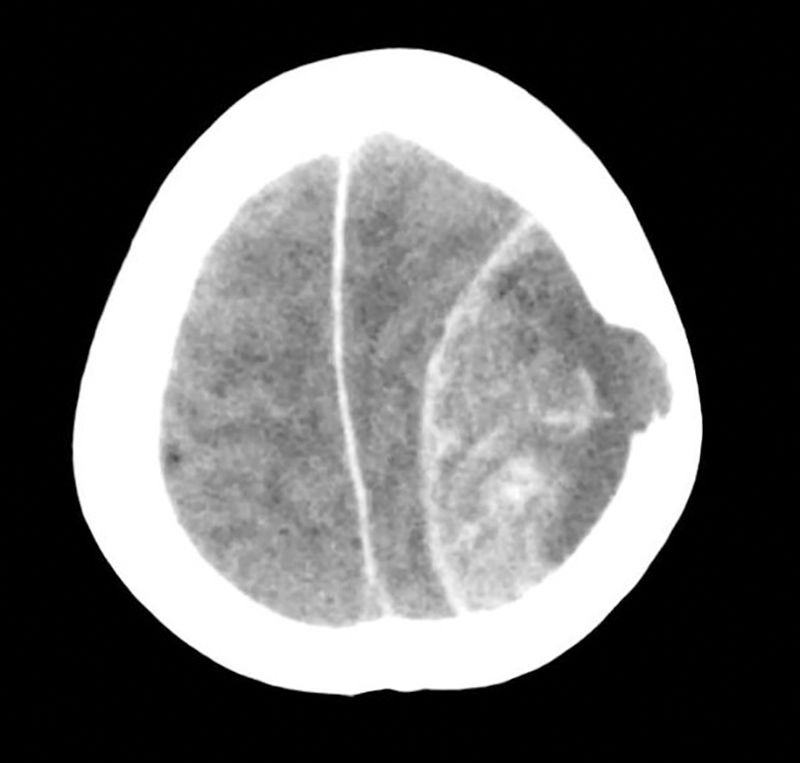

A 59-year-old Thai woman living in Spain for the past 20 years with a personal history of a partial nephrectomy and hysterectomy, who was not taking any regular medication. She attended our hospital's emergency department having suffered from general malaise, abdominal distension, jaundice and choluria over the course of two weeks, with her symptoms worsening in the second week. While having her history taken, she mentioned that she had received a blood transfusion in the 1980s. She said she did not take any medicines, herbal products or have tattoos. She travelled often, having visited Thailand and Switzerland in the last year. She had consumed 16g of alcohol per day for the past five years. During the physical examination, she presented jaundiced skin and mucous membranes and painless hepatosplenomegaly. Her laboratory tests revealed a previously unknown coagulopathy and abnormal liver parameters: total bilirubin 8.11mg/dl, direct bilirubin 5.85mg/dl, GOT 368U/l, GPT 137U/l, GGT 625U/l, AP 190U/l, CRP 14.39mg/dl and prothrombin activity of 53%. Twenty-four hours after admission, she presented a sudden-onset intense holocranial headache and a rapid decline in consciousness (Glasgow Coma Score [GCS] of 5), with no focal neurological deficit. The patient was transferred to intensive care, where she underwent orotracheal intubation and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the head with intravenous contrast. The CT scan (Fig. 1) revealed the presence of a left-sided frontoparietal acute epidural haematoma (AEH) measuring 85×42mm, with associated intracranial expansion and hypertensive hydrocephalus in the contralateral ventricle, probably secondary to an osteolytic cranial vault lesion, suggesting a metastatic aetiology. She underwent emergency neurosurgery, with a left frontotemporal craniotomy, evacuation of the haematoma and tumour resection.

The patient presented poor clinical progress, maintaining a GCS score of 3–4 as well as anuria. From a gastrointestinal point of view, an abdominal ultrasound was performed, showing liver cirrhosis with a focal heterogeneous lesion in segment II measuring 4cm, a partial portal vein tumour thrombus with a hepatofugal flow and mild ascites. Her blood work up tested positive for the hepatitis C virus (HCV) antigen and antibody, with raised alpha-fetoprotein (2476ng/ml). According to both clinical and analytical data, she presented a Child-Pugh score of C14 and a MELD score of 24. An anatomical pathology study of the skull lesion (bone and epidural) revealed the presence of epithelial tumour cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, prominent nuclei and a trabecular structure, compatible with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) metastases. In the end, the patient died four days after surgery.

The incidence of HCC is less than 5% and it is typically located in the lungs (34–70%) and lymph nodes (16–40%). Bone metastases make up 1.6–16%, generally in the vertebrae, pelvis and ribs, being rare in the skull (0.4–1.6%).1

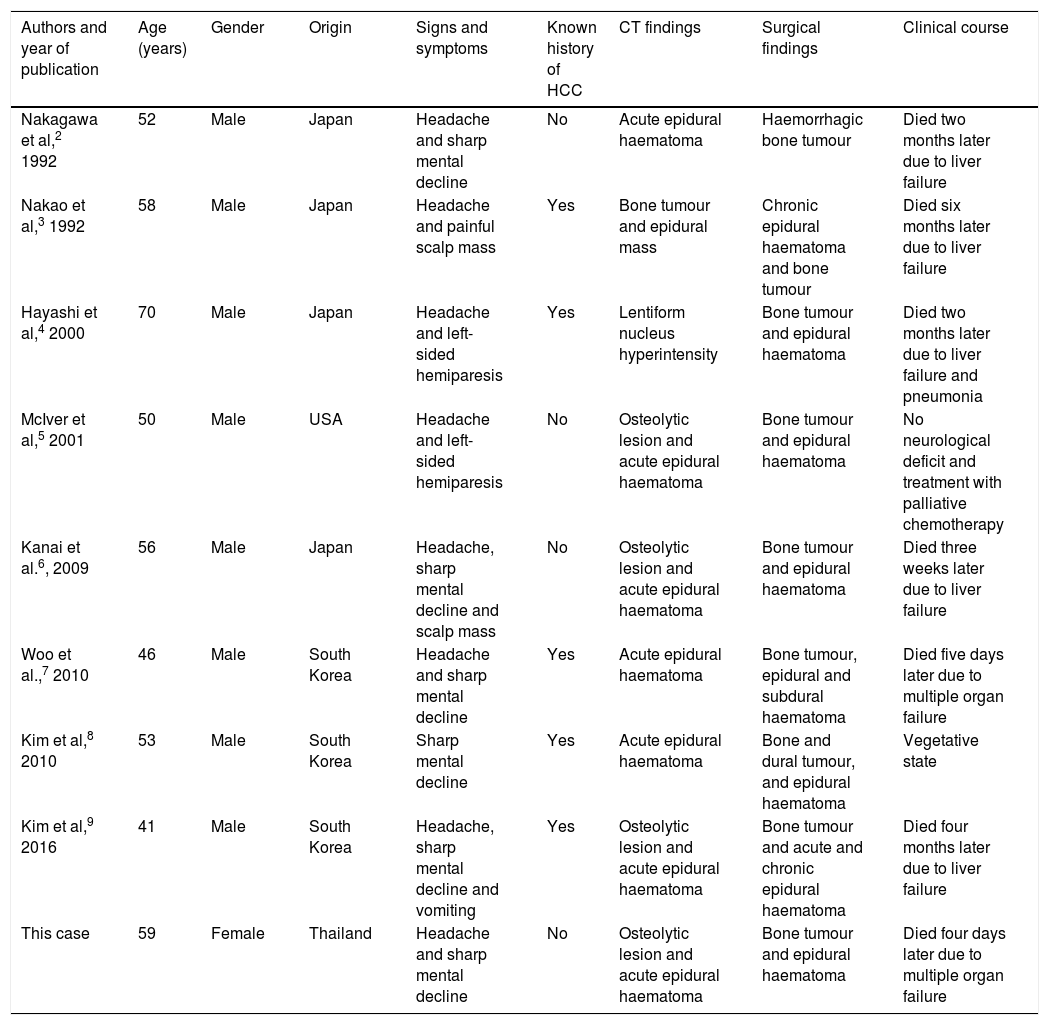

An AEH usually develops secondary to a traumatic brain injury, but may arise spontaneously in the context of neoplastic diseases, infections, vascular malformations or coagulation disorders. Intracranial haemorrhage secondary to metastasis is rare, with an incidence of 0.9–11%. They usually occur within a tumour or the brain itself, and very rarely in the epidural area.6–8 The formation of an AEH secondary to a HCC metastasis is very rare. In the literature reviewed, we found just eight published cases, as set out in Table 1.2–9 According to this review, they generally affect Asian males, with or without a history of known liver disease, who present with a headache and sharp mental decline. AEH is diagnosed by CT, although bone lesions are only observed in half of cases. All patients undergo surgery and the prognosis is poor, either due to the AEH itself or liver failure. It should be noted that this is the first case reported in a female.

Summary of published cases of patients with a spontaneous AEH due to HCC metastasis.

| Authors and year of publication | Age (years) | Gender | Origin | Signs and symptoms | Known history of HCC | CT findings | Surgical findings | Clinical course |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nakagawa et al,2 1992 | 52 | Male | Japan | Headache and sharp mental decline | No | Acute epidural haematoma | Haemorrhagic bone tumour | Died two months later due to liver failure |

| Nakao et al,3 1992 | 58 | Male | Japan | Headache and painful scalp mass | Yes | Bone tumour and epidural mass | Chronic epidural haematoma and bone tumour | Died six months later due to liver failure |

| Hayashi et al,4 2000 | 70 | Male | Japan | Headache and left-sided hemiparesis | Yes | Lentiform nucleus hyperintensity | Bone tumour and epidural haematoma | Died two months later due to liver failure and pneumonia |

| McIver et al,5 2001 | 50 | Male | USA | Headache and left-sided hemiparesis | No | Osteolytic lesion and acute epidural haematoma | Bone tumour and epidural haematoma | No neurological deficit and treatment with palliative chemotherapy |

| Kanai et al.6, 2009 | 56 | Male | Japan | Headache, sharp mental decline and scalp mass | No | Osteolytic lesion and acute epidural haematoma | Bone tumour and epidural haematoma | Died three weeks later due to liver failure |

| Woo et al.,7 2010 | 46 | Male | South Korea | Headache and sharp mental decline | Yes | Acute epidural haematoma | Bone tumour, epidural and subdural haematoma | Died five days later due to multiple organ failure |

| Kim et al,8 2010 | 53 | Male | South Korea | Sharp mental decline | Yes | Acute epidural haematoma | Bone and dural tumour, and epidural haematoma | Vegetative state |

| Kim et al,9 2016 | 41 | Male | South Korea | Headache, sharp mental decline and vomiting | Yes | Osteolytic lesion and acute epidural haematoma | Bone tumour and acute and chronic epidural haematoma | Died four months later due to liver failure |

| This case | 59 | Female | Thailand | Headache and sharp mental decline | No | Osteolytic lesion and acute epidural haematoma | Bone tumour and epidural haematoma | Died four days later due to multiple organ failure |

AEH: acute epidural haematoma; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma.

The literature review performed by Hsieh et al.1 gathers a total of 68 cases of skull metastases due to HCC. The most common form of presentation is a subcutaneous mass, although 10% of patients present intracranial haemorrhagic events. It is not known why these types of metastasis cause AEH, although the most widely accepted hypothesis posits that it is due to the breakdown of vessel structures in the peritumoral tissue, secondary to tumour growth.1,9

In conclusion, we should consider the existence of skull metastases in patients with HCC, particularly if they present with neurological signs and/or symptoms. We should also keep in mind the risk of fulminating AEH.

Please cite this article as: Delgado Maroto A, del Moral Martínez M, Diéguez Castillo C, Casado Caballero FJ. Hematoma epidural agudo como presentación de carcinoma hepatocelular: a propósito de un caso y revisión de la literatura. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;42:177–179.