Mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid or 5-ASA) is the standard treatment for the induction and maintenance of mild/moderate flare-ups of ulcerative colitis (UC). The anti-inflammatory mechanism is not known; it is postulated that there is an increase in the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in the intestinal mucosa and the cyclooxygenase pathway is inhibited.1 Mesalazine is a safe drug that is widely used in clinical practice. Various adverse effects have been described with a low incidence and variable severity, which may lead to the drug being withdrawn. The most frequent are: arthromyalgia, abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhoea and headache. These side effects are not dose-dependent; they are due to hypersensitivity reactions and not to cumulative toxicity.1

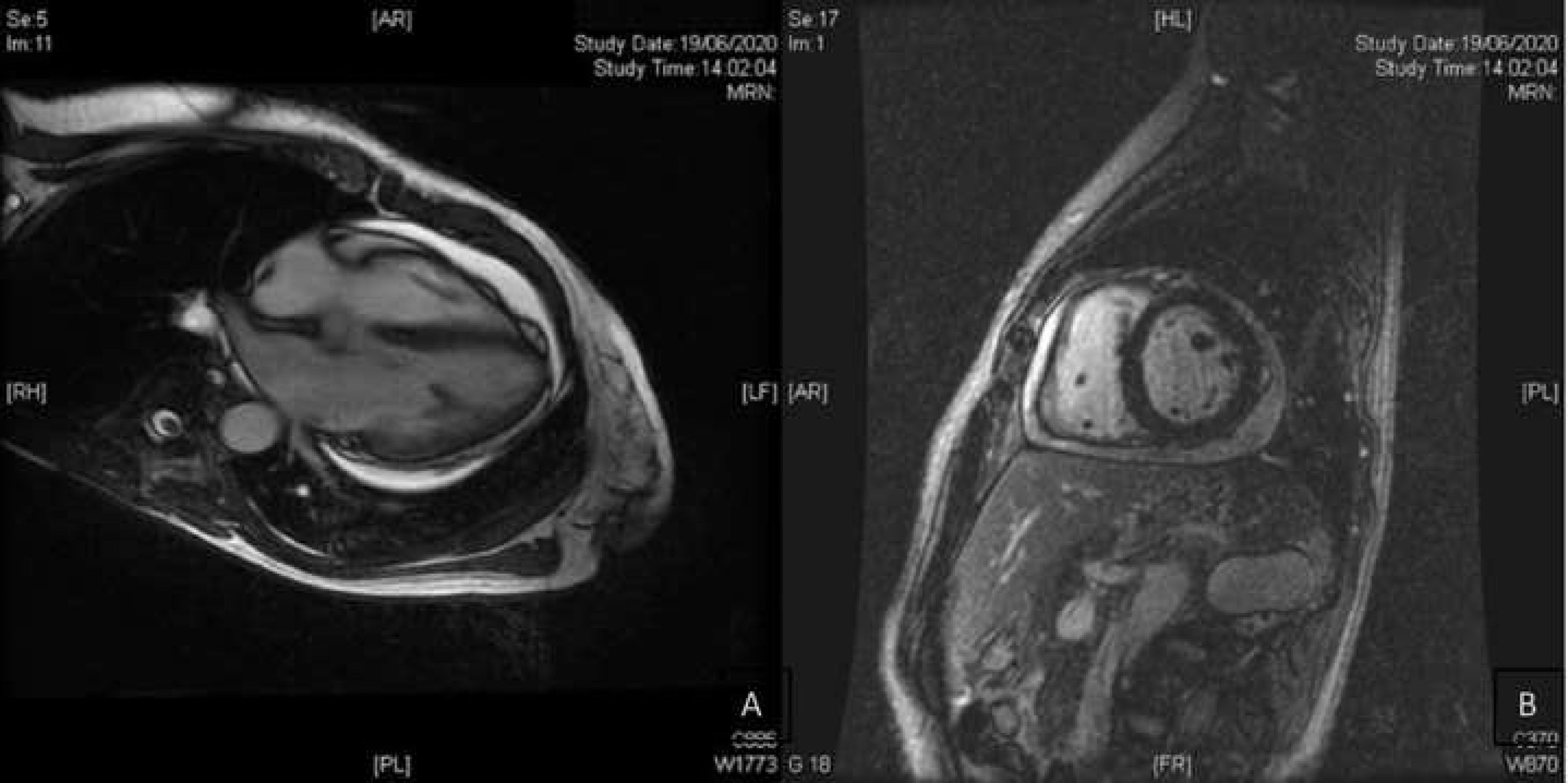

We present the case of a 53-year-old woman, with no relevant history, diagnosed with ulcerative proctitis at another medical centre in February 2020. Treatment with oral mesalazine (500 mg/8 h) and mesalazine foam (one nocturnal application) was started at that time. She was admitted to the centre in May 2020 due to a moderate outbreak of left UC, undergoing abdominal pelvic computed tomography (CT). The CT scan showed proximal extension of the disease to the sigmoid area and a small pericardial effusion (PE). She was transferred to our hospital after a lack of response to intravenous corticosteroids for 10 days (methylprednisolone 60 mg/24 h). Cytomegalovirus infection was ruled out by rectal biopsy as the cause of corticosteroid refractoriness and treatment was started with infliximab (5 mg/kg), maintaining oral mesalazine (4 g/24 h). Given her good clinical response and test results, she was discharged from hospital. She came to the emergency department two weeks later having had fever for three days, with evening peaks of up to 38.5 °C without other associated symptoms or abdominal symptoms, and without an increase in the number of stools or bleeding. Laboratory tests showed an elevation of acute phase reactants (C-reactive protein of up to 8.9 mg/dl). An urgent abdominal CT scan was performed which identified proctosigmoiditis without local complications and worsening of the pericardial effusion. The study was completed with a transthoracic echocardiogram with a finding of a moderate effusion (17 mm) without haemodynamic compromise. The patient was admitted for study of fever without focus and PE. A rectoscopy was performed, in which a clear improvement was observed compared to the previous examination, so, given the absence of compatible symptoms, UC activity was ruled out as a cause of the fever and elevation of acute phase reactants. The PE study ruled out an infectious cause (negative PCR for respiratory viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, in nasopharyngeal exudate), as well as tumour and autoimmune causes. In the autoimmunity study, there was positivity only for p-ANCA. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (Fig. 1) confirmed moderate effusion and ruled out acute pericarditis or other pericardial involvement. Mesalazine was suspended as a possible causative drug and infliximab was ruled out as a cause of PE, since it was observed weeks before the drug was started. During admission, after suspension of mesalazine, the patient remained afebrile without antibiotics, antipyretics and normalisation of acute phase reactants. A follow-up echocardiogram one month after hospital discharge showed the practical resolution of PE (minimum effusion <5 mm). The patient remained afebrile after discontinuation of mesalazine two months after admission.

Cardiac side effects related to mesalazine are reported with a frequency from 0 to 0.3%.1 Among them are: cardiomyopathy, acute myocardial infarction and atrioventricular blocks.1 Involvement of the pericardium, myocardium, or both (myopericarditis) is rare, but can be potentially serious and requires early detection and treatment.2 The pathophysiology of cardiac toxicity due to mesalazine is not known, and humoral (IgE-mediated) and cellular mechanisms or direct toxicity are postulated.3

In our patient, the finding of PE was incidental, since the clinical, laboratory and electrocardiogram findings were not compatible with myopericarditis. It was not accompanied by pleural effusion, positive autoimmunity (except p-ANCA, relatively common in patients with UC), or any other extraintestinal manifestation compatible with mesalazine-induced lupus. The cases of PE described in the literature are exceptional. The diagnosis is made by exclusion and from the temporal relationship with the introduction of the drug.4

In summary, mesalazine is an effective and safe drug, although cardiac side effects have been reported exceptionally. There should be a high clinical suspicion and a broad differential diagnosis should be made and, in the event of a potential causal relationship, the drug should be discontinued and not reintroduced due to the high risk of recurrence.5

Conflicts of interestJavier Gisbert has provided scientific advice and support for research and/or training activities for MSD, Abbvie, Pfizer, Kern Pharma, Biogen, Mylan, Takeda, Janssen, Roche, Sandoz, Celgene, Gilead, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma, Chiesi, Casen Fleet, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Vifor Pharma.

Please cite this article as: Ezquerra A, Resina E, Montes Á, Álvarez-Malé T, Gisbert JP. Derrame pericárdico asociado al tratamiento con mesalazina en un paciente con colitis ulcerosa. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:721–723.