Entrepreneurial self-efficacy holds significant importance due to its broad influence, benefiting not just entrepreneurs but also extending its impact to other domains. This is why it is so important to have an understanding of the factors that are at its core. Our primary aim is to investigate the influence of family communication on entrepreneurial success. In doing so, we will explore mediating factors, with a particular focus on entrepreneurial self-efficacy.

In 2021, we carried out a survey targeting entrepreneurs, utilizing four self-descriptive questionnaires for data collection purposes. Family Assessment Scales, The Entrepreneur's Family Communication Questionnaire, The Entrepreneurship Efficacy Scale, and The Questionnaire of Entrepreneurial Success. The study involved conducting descriptive, correlation, and path analyses.

The findings indicate that family communication plays a crucial role as a psychological factor in elucidating entrepreneurial success.

In the 21st century, prosperity seems to have emerged as the dominant value and primary existential goal for the majority of societies. National economies are striving to increase GDP, workers are seeking better working conditions and significantly higher wages, and the demand for a range of material goods is increasing not only among adults but also among children. Entrepreneurship has emerged as a critical factor in achieving prosperity at both the micro and macro levels. Certainly, not every entrepreneurial endeavor leads to the anticipated, primarily economic, outcomes, and not all entrepreneurs achieve success. Entrepreneurial success is a subject that has been extensively explored in various studies (Alroaia & Baharun, 2018; Angel et al., 2018; Berge & Pires, 2019; Constantinidis et al., 2019; González Sánchez, 2018; Razmus & Laguna, 2018; Staniewski & Awruk, 2018; Torres Marín, 2020). Naturally, the definition of entrepreneurial success varies, as researchers measure the phenomenon differently, and entrepreneurs perceive it in diverse ways. Researchers also identify diverse factors that condition or support entrepreneurial success.

Each year, a growing number of these factors are identified in the literature, with researchers exploring them through insights from various disciplinary perspectives, such as economics, psychology, sociology, and anthropology (Van, 2003). In recent years, the psychological approach has become more prominent. Researchers are moving away from the traditional economic approach and incorporating various psychological theories to shed light on the concept of entrepreneurial success. This trend emphasizes the growing significance of the family, including the entrepreneur's family of origin (Shakeel et al., 2020; Staniewski et al., 2023; Welsh & Kaciak, 2019). The family can influence an entrepreneur's success in a variety of ways, and family communication may be one example of such influence (Staniewski et al., 2023).

This study seeks to conduct a more detailed analysis of how family communication influences entrepreneurial success. It aims to explore the underlying mechanisms and factors contributing to the impact of family communication on the success of entrepreneurs. In addition, we wanted to explore how one of the paths of influence, namely between family communication and entrepreneurial success, behaves when the mediators are changed. We opted to substitute the mediators from the variables explored by Staniewski et al. in 2024—namely, achievement motivation and self-esteem—with entrepreneurial efficacy or self-efficacy, recognizing the latter as another crucial predictor of entrepreneurial success. To illustrate, we constructed a theoretical model (Fig. 1):

Theoretical frameworkWorld literature is abundant with numerous and impactful scientific works that delve into research findings specifically focused on the subject of entrepreneurial success. Their authors identified a number of factors affecting entrepreneurial success, which can generally be divided into three large groups: economic, social, and psychological (Abu et al., 2014; Agarwal & Dahm, 2015; Baron & Markman, 2003; Baron & Tang, 2009; Green & Pryde, 1989; Joona, 2018; Kalleberg & Leicht, 1991; Sassetti et al., 2019).

An increasing importance is given specifically to psychological factors, such as personality traits, self-esteem, social support networks, and passion, as highlighted by Staniewski and Awruk (2021). Moreover, the moral and emotional support from the family, along with support originating from the social structure—encompassing family, social life, and family communication—assume progressively vital roles (Hoang & Antoncic 2003; Liao & Welsch 2005; Prasad et al., 2013; Shakeel et al., 2020; Staniewski et al., 2023; Welsh & Kaciak, 2019).

Within this cluster of psychological factors, effective communication within the family—specifically tied to one's family of origin—appears to have a fundamental influence. According to Olson (2000), family communication is the collective exchange of ideas, participation in decision-making, and the expression of emotions among family members, acting together as a cohesive unit. An important element of parent-child interaction is family communication (Orm et al., 2021).

Parents and children use family communication as a tool to adjust their roles and nurture their relationships (Tesson & Youniss, 1995). This process facilitates their progress toward greater mutual understanding and commitment. When distilled to the exchange of information between parent and child subsystems, family communication constitutes the core of the parent-child relationship (Orm et al., 2021). It is a developmental process that starts in the earliest stages of a child's life, as parent-child communication initiates during infancy. In this phase, children express their needs through crying, and parents respond, with varying degrees of accuracy (Acebo & Thoman, 1995). This communication begins the attachment process, during which the reciprocal influence between the children and the parents creates a relationship that is vital for future mental health and overall well-being (McCarty & McMahon, 2003). Therefore, communication within the family provides the environment in which various types of attachment and social skills are developed. Early on, children are exposed to social and cultural content that is essential for their integration into society. This is done through socialization within the family unit, as emphasized by Musitu and Cava (2001). In light of the preceding information, communication within the family appears to be an indispensable element in the family environment. It is particularly important in the development of children. Communication within the family is instrumental in numerous processes related to the underlying aspects that facilitate learning experiences for social achievement (Iaza & Henao, 2011). From a more holistic point of view, family communication is a process that spans generations and is characterized by the transmission of information across generations. Within this framework, family members share a common set of norms, traditions, and values, fostering an ongoing exchange that shapes family communication practices over an extended time frame (Baxter et al., 2005; Fitzpatrick, 2004; Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2002; Savita Gupta, 2019).

The communication styles within families have a significant impact on the way in which children develop attitudes and convictions within the family setting, as indicated by Koerner and Schrodt (2014). In families that exhibit a conversation pattern, the prominence of family roles and social positions in defining the aspirations of the family is reduced. Such families foster a supportive environment through open discussion of a variety of issues and ideas (Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2002). Children who grow up in conversational families often demonstrate enhanced social networking and information-processing skills. They tend to show curiosity in exploring new concepts, open-mindedness when confronted with unfamiliarities, and creativity in generating independent thoughts. In addition, such children tend to demonstrate confidence in navigating situations of uncertainty on their own (Koerner & Schrodt, 2014; Sciascia et al, 2013). These qualities contribute to boosting children's self-assurance in handling entrepreneurial responsibilities (Jaskiewicz et al., 2017; Soleimanof et al., 2019). Increased levels of entrepreneurial self-efficacy allow these children to have confidence in their ability to effectively embark on a career as an entrepreneur (Santoro et al., 2020a).

Family conversations and interactions equip children with entrepreneurial knowledge and decrease their uncertainty about starting a career as an entrepreneur. At the same time, these engagements play a role in increasing their self-efficacy, fostering confidence in undertaking entrepreneurial endeavors independently (BarNir et al., 2011). As a whole, children brought up by enthusiastic business owners who demonstrate a conversational approach develop entrepreneurial skills and knowledge throughout their lives. This exposure positions entrepreneurship as a viable and realistic career choice for them (Soleimanof et al., 2021).

The aforementioned self-efficacy is, according to many researchers, a factor that supports the achievement of entrepreneurial success (Khalil et al., 2021; Kimathi et al., 2019; Miao et al., 2017; Santoro et al., 2020). Bandura (1977) defines self-efficacy as an individual's belief in their ability and confidence to execute specific behaviors or tasks to achieve personal goals. In addition, he posits that individuals can adapt and self-regulate to achieve their envisioned goals (Bandura, 1986). Self-regulation encompasses cognitive processes that empower individuals to govern and guide their actions, evaluate their progress, and make necessary adjustments, all aimed at accomplishing meaningful goals (Baron et al., 2016). Self-regulation is frequently characterized as an individual's capability of undertaking challenges and managing private activity.

Within the entrepreneurial framework, the concept of self-efficacy is rooted in Bandura's theoretical framework (1982). In the entrepreneurial context, this efficacy pertains to the perceived ability to accomplish various activities, such as locating suitable business premises, securing financial resources, or managing the recruitment and training of personnel. Confidence in own entrepreneurial efficacy is defined as "the strength of a person's belief that he or she is capable of successfully performing the various roles and tasks of entrepreneurship" (Chen et al., 1998). While this concept is distinct from entrepreneurial success, it is becoming the focus of empirical and theoretical research that seeks to delineate the factors that contribute to entrepreneurial success.

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy, as defined by Boyd and Vozikis (1994) and Campo (2011), refers to the extent of one's belief in the capability to successfully initiate a new business venture. Additionally, it is characterized as an individual's confidence in conducting entrepreneurial activity, encompassing the belief in potential success (McGee et al., 2009), own assurance in own competencies during the startup process (Chen et al., 1998; Segal et al., 2005), and the element facilitating the successful initiation and administration of a company (Carter et al., 2003; Rauch & Frese, 2007).

Bandura (1977) highlighted its significance in entrepreneurship as it impacts not just the decision to start a company but also the dedication in the face of challenges and the extent of effort invested. When starting a business, business owners evaluate their ability to set a course that will lead to the successful attainment of an outcome. This is what is referred to as goal beliefs. With the ability to achieve entrepreneurial goals, individuals with high self-efficacy are more inclined to envision the potential for substantial gains, public acclaim, and self-gratification, while at the same time being able to anticipate failure (Abualreesh et al., 2023).

The examination of entrepreneurs with high and low levels of success through comparative and profile analyses revealed that those with high success tend to exhibit greater flexibility, dominance, self-appraisal, and self-efficacy. They also demonstrated elevated business efficacy, such as in acquiring information (Staniewski & Awruk, 2019). In accordance with the research conducted by Srimulyani and Hermanto (2021), heightened levels of entrepreneurial self-efficacy correspond to increased success in business.

Drawing from the literature discussed earlier, we made assumed that:

H1 Family communication (understood as the level of satisfaction with the way family members communicate, subscale SOR) is related to entrepreneurial success in such a way that higher satisfaction with said communication is associated with higher levels of entrepreneurial self-efficacy, which translates into higher levels of entrepreneurial success.

However, based on our previous research, the dimensions of family communication (discussed in the literature) in the context of entrepreneurship, we have distinguished two types of communication: 1) nonspecific communication and 2) specific communication (Staniewski et al., 2023). Nonspecific communication involves general expressions where parents provide support, praise, foster open discussions, and encourage their children to freely express views and opinions. On the other hand, specific communication directly addresses entrepreneurial activity. This may manifest as family (of origin) support for entrepreneurship, including endorsing business ideas, highlighting entrepreneurial traits, approving creativity, and acknowledging persistence in achieving goals. Alternatively, it can involve discouraging and depreciate entrepreneurial behavior by emphasizing the risks associated with starting a business and dissuading individuals from pursuing entrepreneurship. If we take into account the above arguments and the distinction of the two types of family communication, we additionally assume that:

H2 Without prejudice to the path of associations tested in H1, with the mediational role of self-efficacy between family communication and entrepreneurial success, a higher level of specific family communication (the one in which the parent directly refers to the person's entrepreneurial predispositions) is also linked to a higher level of entrepreneurial success.

A qualified interviewer, chosen through a competitive selection process, carried out the survey from May to December 2021. On the condition that the selected entrepreneurs had been operating in Poland for at least three years, the entrepreneurs were randomly selected from Poland's publicly available Central Registration and Information on Business directory (Centralna Ewidencja i Informacja o Działalności Gospodarczej [CEIDG]). Entrepreneurs participating in the study were extended invitations via telephone. Of the 600 individuals who received invitations, 334 agreed to participate. However, only 182 of them successfully completed the questionnaires analyzed in this study, resulting in a response rate of 59.9% and a completion rate of 54.5%. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26 for Windows and Jamovi 2.3.

Tools- 1.

Family Assessment Scales(FAS). This is a Polish adaptation of H. Olson's FACES-IV D by A. Margasiński (2015). The purpose of the questionnaire is to assess the functioning of a family. The respondent's task is to provide answers to 62 questions on a 5-degree scale (from ‘completely disagree’ to ‘completely agree’ for questions 1-52 and from ‘very dissatisfied’ to ‘very satisfied’ for questions 53-62). The questionnaire consists of eight scales, six of which are the main scales that are derived from the Circumplex Model developed by David H. Olson. These scales address two dimensions of family functioning, specifically cohesion, and flexibility (i.e., balanced cohesion, disengagement, enmeshment, balanced flexibility, rigidity, and chaos). The two remaining scales measure communication, which is also the third dimension of the Circumplex Model, and satisfaction with family life. Apart from the scores on the individual scales, the tool measures three complex indicators: cohesion, flexibility, and the total score, which is the measure of the appropriate functioning of a family. The following are some examples of items in this questionnaire: Family members are able to calmly discuss problems; family members try to understand each other's feelings; in our family, it is important to follow rules.

- 2.

The Entrepreneur's Family Communication Questionnaire (EFCQ) is a 39-item tool by Staniewski et al. (2023) to measure non-specific and specific communication in entrepreneurs' families. Non-specific communication includes messages focused on support from family members (support subscale), giving each other space to openly express opinions, share opinions, and views (openness subscale), and criticizing and devaluing (depreciation subscale). Specific communication, however, refers to messages referring directly to entrepreneurial activity - supporting, encouraging entrepreneurial activity (support for entrepreneurial behavior subscale) or discouraging it, depreciating the entrepreneurial potential of the respondent (depreciation of entrepreneurial behavior subscale). The results are calculated by aggregating the score of a given subscale. The higher the score, the higher the intensity of a dimension. The respondent's task is to address each statement by selecting one of five possible answers from Never to Always. Here are some examples of included items: In my family home, any business idea ended up being laughed at/negated; In my home, I was discouraged from starting my own business; I was told that it required a lot of dedication and resources (financial background, connections, premises, etc.); When I had a problem, I could seek advice from my parents.

- 3.

The Entrepreneurship Efficacy Scale (EES) This is a 21-item tool developed by Łaguna (2006) that measures the conviction about one's efficacy in terms of setting up a business. The questionnaire comprises 3 subscales: Efficacy of collecting market information (6 test items), Financial and legal efficacy (5 test items), and Efficacy of business activity (10 test items). The scores are calculated by dividing the total number of points in the whole questionnaire and the number of points in the subscales by the number of statements to demonstrate the mean intensity of the conviction about one's own efficacy. A higher score indicates a greater intensity of this conviction. The respondents provide a response on a 100-degree scale, where 0 means I cannot do it at all and 100 means I am sure I can do it. The Cronbach's alpha demonstrates the reliability of the whole scale to be 0.96 and the Guttman's split-half reliability coefficient is 0.87.

- 4.

The Questionnaire of Entrepreneurial Success (MQES) is a 24-item tool by Staniewski, Awruk, and Leonardi to measure entrepreneurial success (Staniewski et al., 2023). The questionnaire asks the respondent to address each statement by selecting one of two possible answers (yes/no). In the MQES, it is possible to count only the total score, calculated by adding up the points obtained on all 24 items. A higher score indicates a higher intensity of entrepreneurial success. Here are a few example items: Do you feel that you have been successful in running your business? Do you find satisfaction in building your own career in the long term? Do you maintain liquidity in your business (cover current bills/commitments/salaries on time, etc.)?

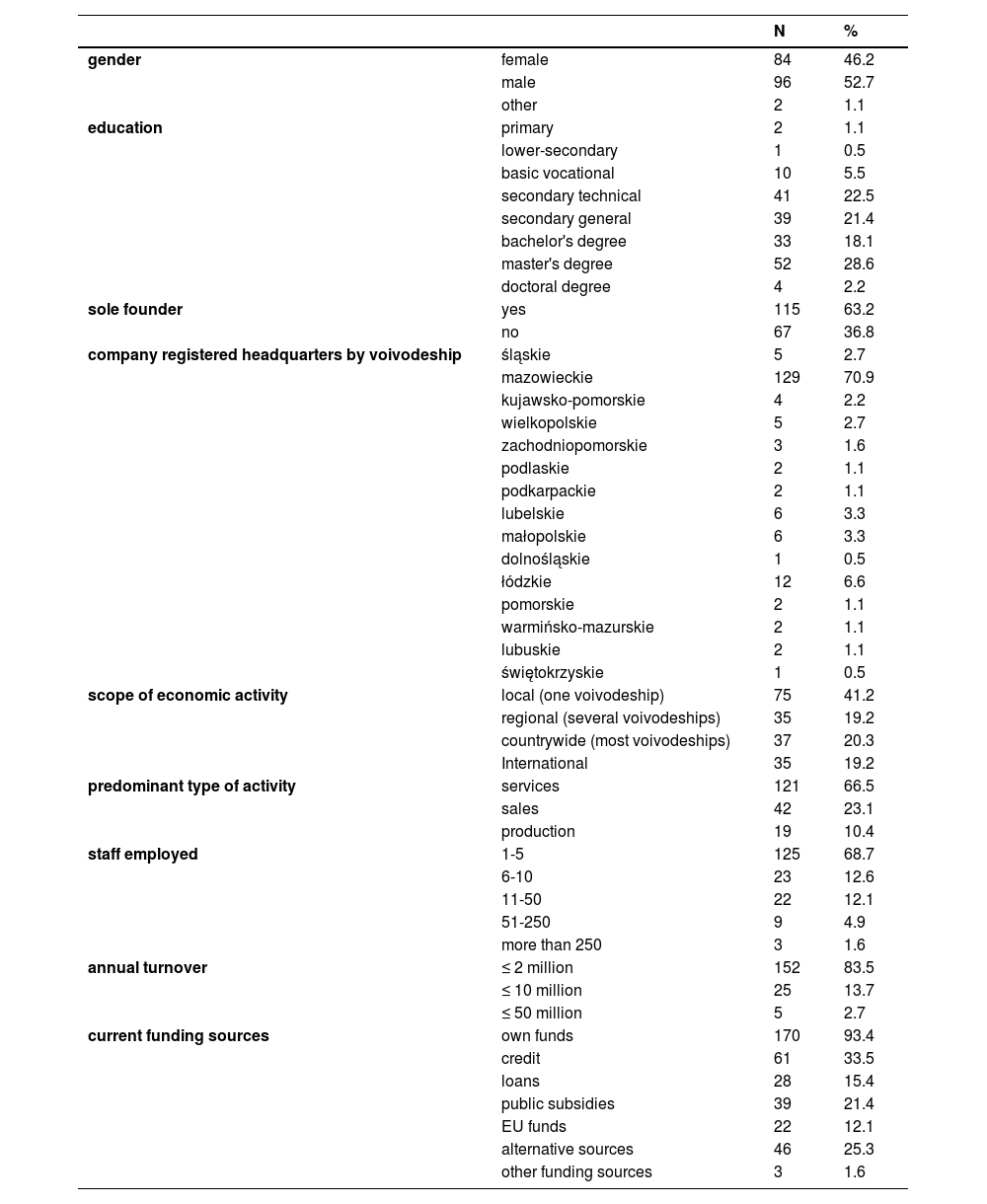

The sample considered consisted of 182 entrepreneurs conducting business in Poland for a minimum of three years. In Table 1 a range of detailed demographic characteristics of this sample is provided.

The sample categorized by sociodemographic variables and economic activity.

The mean business operation period for all participants was about 12 years (SD=9.4). Respondents' age ranged from 21 to 74 years (M=40.44; SD=11.43). Around 46% of the respondents identified as women and 53% as men, while another two respondents (∼1% of the sample) declared that they were of a different gender. Almost half of the sample had a bachelor's or higher degree (bachelor, master, or doctoral degree: 48.9%), while another considerable group (about 44%) completed secondary education. Only a minority of respondents had basic vocational education (5.5%), primary education (1%), and lower-secondary education (0.5%).

The majority of respondents reported that they were the sole founder of their company (63.2%). Most of the companies were run in the central Mazovian Voivodeship (71%), the region of the Polish capital, Warsaw. These were mainly small enterprises, employing 1 to 5 people (68.7%), local in scope (41.2%), operating in the service sector (66.5%), with an annual turnover of less than 2 million (83.5%).

ResultsWe performed descriptive, correlation, and path analyses.

DescriptivesWhen considering the variables which are the focus of this study at a general, descriptive level, we can observe that the mean level of Entrepreneurial Success (M=19.8, SD=6.07) and Entrepreneurial Efficacy (M=73.2, SD=15.46) were relatively high, with a concentration of scores in the right tail of the distribution (negative skewness). This pattern tells us that entrepreneurs studied in our sample were relatively successful and effective according to these psychometric tools (see Table 2).

Descriptive statistics of the variables considered in the study.

A similar pattern can also be observed for the balanced scales of the family life evaluation tool (Balanced Cohesion and Balanced Flexibility) as well as for the Communication and Life Satisfaction scales. This fact, combined with a somehow opposite pattern in the unbalanced scales of FACES-IV (Disengagement, Enmeshment, Rigidity, and Chaos), namely, relatively low average values at those scales together with positive skewness (concentration of values in the lower scores’ tail of the distribution), leads us to the conclusion that the families of the participants to the study were in general rated in positive terms and healthy by them.

When it comes to the two scales of our signature tool on Communication within the entrepreneur's family (EFCQ - Entrepreneurial Specific and Non-specific Communication) we see that the Non-specific Communication scale tends to have a relatively high average score (M=50.8, SD=16.08) and negatively skewed distribution, consistent with the results at the FACES IV-Communication scale, while the Specific Communication scale has a more symmetric distribution around its average value (M=28.8, SD=9.34, Skewness=-0.05).

In Table 2 the main descriptive statistics relative to the variables used in this study are presented in their entirety.

CorrelationTable 3 shows the correlation matrix of the variables evaluated in the path analyses and used to determine whether or not the data fit the model.

Correlation matrix of the variables considered in the study (N=182).

Note. * p < .05, ⁎⁎ p < .01, ⁎⁎⁎ p < .001

We can see that in general most of the variables are positively correlated between them, with the exception of the unbalanced scales of the FACES-IV questionnaire, which, as a rule, are negatively or not significantly correlated with the other scales of the same questionnaire and with the two scales measuring Entrepreneurial Success and Efficacy. Those unbalanced scales (Disengagement, Enmeshment, Rigidity, and Chaos) are however moderately to strongly positively correlated among them, which is to be expected according to the theory (Olson, 2011). Similarly, the other scales of the FACES-IV questionnaire (Balanced Cohesion, Balanced Flexibility, Communication, and Life Satisfaction) do correlate significantly and strongly among them, and moderately or weakly with Entrepreneurial Success and Entrepreneurial Efficacy. The only exception to this pattern is the correlation between Balanced Flexibility and Entrepreneurial Success which do not reach significance (r=.139 – see Table 3).

Correlations of the EFCQ Communication questionnaire's scales are also mostly significant and moderate with all the other scales considered –in a positive direction with the balanced scales of FACES-IV and Entrepreneurial Success and Efficacy, and in a negative direction with the unbalanced scales of FACES-IV– which is what we would expect.

We can hence anticipate that the unbalanced scales of the FACES-IV questionnaire may not be good predictors in a path model connecting them with Entrepreneurial Success and Efficacy. It also remains to be assessed the role of the balanced scales of FACES-IV and the Communication and Life Satisfaction dimensions of the model.

Path analysesFamily assessment tool (FACES-IV)Looking at the correlation analyses, we found that several FACES IV subscales and the EFCQ general score correlated with entrepreneurial success. This allowed us to proceed with path analyses.

As a first attempt we wanted to consider the influence of all the 8 dimensions of family life assessment tool (FACES-IV) on Entrepreneurial Success, with the mediation role of Entrepreneurial Efficacy. This attempt resulted in a less than satisfying fitting of the data. Both fit indices and parameter estimates of this preliminary analysis were not significant and/or deviated consistently from the accepted benchmark values. Even when initially trimming the complete model from the unbalanced dimensions –which, as we saw, are barely correlated with any of the other variables measured– and successively from the balanced dimensions of the tool, the results are equally not acceptable. These models turned out to be a poor fit, indicating hence that most of the variables related to family structure are not that relevant to entrepreneurial success, but indirectly confirmed that communication may play a crucial role in this network of influences.

In these preliminary analyses indeed, family communication scales (FACES IV-Communication) showed to be an important indicator for entrepreneurial success. For this reason, we formulated a new, more specific model to undergo analysis focusing on family communication as a general factor influencing entrepreneurial success through the mediating role of self-efficacy (see Fig. 1). This was based both on the results of those preliminary analyses as well as on our previous work and theory (Shakeel et al., 2020; Welsh & Kaciak, 2019; Staniewski et al., 2023; Staniewski et al., 2024). We considered Family Communication as the crucial element in a model of family determinants of Entrepreneurial Success, and hence tested the hypothesized model proposed in Fig. 1 by means of structural equation modeling (SEM) for a manifest model. The variables included in this simple model are the FACES-IV Communication scale, the general scores of the EES (Entrepreneurial Efficacy), and our author's MQES (Entrepreneurial Success).

The proposed model proved to fit the data in a fully satisfactory way. Both path coefficients were significant (see Table 4), and all model fit statistics reached the generally accepted benchmark levels. The chi-square test for model fit was not significant χ2 (1)=0.59;p=0.443. All the main fit indices (GFI, CFI, NNFI) reached the maximum value of 1. Moreover, the RMSEA index was 0.00 (with CI95 [0.000; 0.178], p=0.537), and hence in line with the standardly accepted levels of error (Browne & Cudeck, 1993), and the SRMR was 0.016 well within the level of acceptance.

Estimated path analysis coefficients' and variances table.

Given the positive results of the above preliminary, simpler model about the impact of family communication on entrepreneurial success, we decided to introduce a further element in the model by considering communication not only as a general family structure, but also in the more peculiar sense of specific communication related to entrepreneurial activity as captured in our tool of specific communication (EFCQ – Staniewski at al., 2023). We decided to introduce only the specific communication subscale of the tool (EFCQ-Specific communication) as the non-specific subscale could be redundant in the light of the presence of the FACES IV- communication subscale in the previous model, probing similar dimensions, and considering also its lack of correlation with EES scales (see Table 3).

The theoretically proposed tested model was hence as shown in Fig. 2. In the model specific communication within the entrepreneur's family is assumed to have a direct influence on entrepreneurial success, with no mediation role of entrepreneurial efficacy (as measured by EES). In other words, we add to the model tested previously a direct link between (entrepreneurial) specific communication within the entrepreneur's family and entrepreneurial success (see Fig. 2).

The model tested through path analysis, proved to fit the model in a good way (Table 5). The chi-square test for model-fit was not significant (χ2(2)=4.61;p=0.1), which together with good or adequate values of the most commonly used goodness-of-fit indices, seems to support the validity of the proposed model. The Goodness-of-Fit index (GFI) was 0.999 (adj.GFI=0.995), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) was 0.956, both exceeding, hence the benchmark level for those indices. The NNFI was just short of the benchmark value (NNFI=0.898). The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual is below the generally accepted level of <0.08 (SRMR=0.03), and the Root-Mean-Square-Error-of-Approximation (RMSEA) is just above that level (RMSEA=0.085; CI95 [0.000; 0.189], p=.207), however not significantly different from the benchmark level of .05.

Estimated path analysis coefficients' and variances table.

The interesting point to be made here is that while family communication, as measured by the scale of the FACES-IV tool of family assessment seems to have an influence on entrepreneurial success through the mediational role of efficacy, family communication intended as the specific communication related to entrepreneurial behaviors, captured by our proprietary tool EFCQ (Staniewski et al., 2023), seems to have an additional, independent and direct effect on entrepreneurial success without the mediational role of efficacy.

As a final, side note, we also briefly wondered and considered the idea if a different pattern of results could possibly emerge when considering separately the model in the two sub-populations of female and male entrepreneurs. However, when running two separate path analysis with the same structure as the one discussed here (see Fig. 2) in the population of females and males, the results did not diverge from those presented above and in both cases the model fit was altogether very satisfactory. Hence, gender does not seem to be a factor in the path of influences that from communication in the family of origin (structure of non-specific and specific communication) leads to entrepreneurial success with the partial mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy.

DiscussionFor several years, our research has focused on improving and deepening our understanding of the family dynamics that influence entrepreneurial success. We want to improve our understanding of how the family, through its complex and varied influences, either enhances or significantly diminishes the prospects for entrepreneurial success. Initial findings from the study of the "family" mechanism of entrepreneurial success have shown potential (Staniewski & Awruk, 2021). In the original model, we conceptualized and validated, parental autonomy attitudes, modeling, and family communication emerged as significant contributors to the complex mechanism of entrepreneurial success, with general self-esteem and achievement motivation serving as mediators (Staniewski et al., 2024). Intrigued by the dynamics of family communication in the aforementioned model, we opted to shift the perspective of our research slightly to gain a deeper understanding of how family communication influences the development of entrepreneurial success. In this case, our approach aimed to capture communication in two different ways: first, as explicit messages from parents intended to support business efforts (specific communication); and second, as an overall assessment of satisfaction with the overall quality of communication among family members (consistent with the FACES-IV concept). While we confirmed the importance of the former in an earlier study, the latter understanding of communication represents a new quality that extends the model. It was also a deliberate effort to replace previous mediators and introduce a new one into the model - entrepreneurial self-efficacy. This allowed us to verify the role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in explaining entrepreneurial success and also demonstrated the dynamics of family communication when the mediating variable undergoes a shift. This study is another in a series of articles that examine the family factors that influence entrepreneurial success. The objective is to empirically validate a model that examines the importance of family of origin structure and family communication in relation to entrepreneurial success, considering the mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Thus, the variables selected for the model were not arbitrary, and the decision to include self-efficacy as a mediator was preceded by careful consideration of its relevance in explaining entrepreneurial success.

The results obtained lead us to believe that the role of the family system in developing resources important for shaping entrepreneurial success is undeniable. Nevertheless, not all the processes or phenomena taking place within the family of origin appear to hold significance for later business achievements. While this may appear unexpected, both the emotional bond within the family (referred to as cohesion, encompassing mutual closeness, shared interests, and time spent together) and the adaptability of the family system (referred to as flexibility, signifying its capacity for change and the frequency of changes made) seem to have minimal significance in shaping "entrepreneurial” individual resources. In the models we analyzed, we attempted to introduce different configurations of family functioning dimensions (consistent with FACES-IV), each time obtaining low fit coefficients. The results were quite different when family communication was included in the model. It seems to play the largest role among all the family processes analyzed. In line with our initial assumptions, family communication, viewed as messages originating from parents, should be considered in two ways, so to speak. This is due to the distinct impact mechanisms of specific communication compared to those of non-specific communication. The general messages conveyed by parents (non-specific communication) and the degree of satisfaction with such communication appear to play a crucial role in shaping individual resources that can substantially contribute to business-level performance. In the current study, our emphasis is directed towards one of these factors—specifically, the sense of entrepreneurial self-efficacy, defined as the intensity of an individual's belief in their capability to successfully execute diverse tasks and undertake various entrepreneurial roles (Chen et al., 1998). The very concept of self-efficacy in the field of entrepreneurship has already been analyzed several times in terms of its relationship to entrepreneurial intention (Santoso & Oetomo, 2018; Zhao et al., 2005), motivation, achievement (Eliyan et al., 2020; Panić & Milić, 2022), and mental resilience (Czechowska-Bieluga et al., 2023). In our study, we also demonstrated the significant importance (predictive value) of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in the complex process of shaping entrepreneurial achievement. Sense of entrepreneurial self-efficacy was (next to specific family communication) the variable that correlated most strongly with entrepreneurial success. The result obtained is therefore in line with a number of other studies that see entrepreneurial self-efficacy as an important resource for achieving entrepreneurial success. For example, Kaczmarek and Kaczmarek-Kurczak (2019) showed that among 81 entrepreneurs developing in the cultural and creative sectors, entrepreneurial self-efficacy appeared to be a better predictor of entrepreneurial achievement than the overall sense of self-efficacy. Likewise, a separate investigation involving 64 entrepreneurs in the digital sector revealed that, in conjunction with innovation, a strong sense of entrepreneurial self-efficacy emerged as the foremost determinant of entrepreneurial achievement (Dessyana & Riyanti, 2017).

Another interesting result is the type of family communication involved in explaining entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Although it was originally assumed that both types of family communication (non-specific and specific communication) could be significantly involved in the process of developing entrepreneurial self-efficacy, the results obtained did not fully confirm these initial assumptions. As revealed, overall family communication characterized by warmth, attentive listening, a willingness to comprehend, and openness in expressing emotions, rather than specific messages directly related to business activities, played a more significant role in shaping entrepreneurial self-efficacy. This second type of communication (specific communication - promoting, appreciating, and encouraging business activity) was directly related to entrepreneurial success. Despite obtaining direct correlations of specific communication with entrepreneurial achievement in the resulting model, we posit that this form of communication can contribute to the development of various resources beyond entrepreneurial self-efficacy. These reflections affirm prior findings, indicating that specific communication was indirectly associated with entrepreneurial success (Staniewski et al., 2024).

In conclusion, the results obtained confirm the role of the family of origin in achieving entrepreneurial success. Among the various phenomena and processes occurring in the family system, family communication appears to be the most significant process involved in the complex mechanism of forming psychological resources relevant to future entrepreneurial achievement.

ConclusionsThe aim of this study was to analyze the mechanism of the impact of family communication on entrepreneurial success with mediating factors such as entrepreneurial efficacy (self-efficacy). Our first hypothesis specifically assumed the link between family communication and entrepreneurial success through the mediating role of self-efficacy, and the first path model tested based on such a hypothesis showed a good fit to the data, hence supporting it. These findings confirm that general family communication, characterized by warmth, openness, and emotional support, positively influences entrepreneurial self-efficacy, which subsequently contributes to entrepreneurial success. This pathway emphasizes that self-efficacy serves as a critical psychological resource fostered through family communication, underscoring the importance of relational dynamics within the family in the development of entrepreneurial skills.

Additionally –and due to our previous work– we also know that family communication can also be specific to entrepreneurial predispositions and entrepreneurial behavior and in the context of testing the influence of family communication on entrepreneurial success we wanted to integrate this type of communication in the model tested. Our second hypothesis assumed a direct link between specific communication (i.e., about entrepreneurial behaviors and predispositions) in the family of origin and entrepreneurial success, without, however, the mediating role of self-efficacy in this case. The second path model tested, incorporated this additional link, and in this case too, the model proved to fit the data very well, giving hence empirical support to this second hypothesis. This finding suggests that communication specifically directed toward entrepreneurial endeavors, such as encouragement of risk-taking, resilience, and persistence, directly supports entrepreneurial success, operating independently of self-efficacy as a mediator. Thus, while general family communication nurtures self-efficacy, specific communication appears to contribute directly to success outcomes by shaping an entrepreneur's strategic and behavioral approaches. Once again, we have demonstrated the importance of family communication for entrepreneurial success.

Thus, family communication is an important psychological variable in explaining entrepreneurial success. The literature indicates that predictors of entrepreneurial success include achievement motivation, self-esteem, and sense of self-efficacy. We have already verified this - they are important predictors, but our research shows that they are linked through family communication. It is family communication and not, for example, the way the family functions or is structured that has a significant impact those predictors. This highlights family communication as a pivotal influence, functioning beyond static family structure or cohesion to actively shape psychological resources, such as self-efficacy, that are integral to entrepreneurial success. We are therefore close to understanding this complex mechanism.

However, the mechanism of influence of family communication is different when the mediators are self-esteem and achievement motivation (demonstrated in a previous study; Staniewski et al., 2024), and different when it is the sense of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. In the previous study, specific communication had only an indirect effect on entrepreneurial success, whereas, in the current study, we find that specific communication can also have a direct effect, confirming our initial hypotheses. This contrast underscores that while general communication supports entrepreneurial outcomes indirectly, specific communication holds a unique and direct influence on entrepreneurial success. This direct effect suggests that family messages explicitly affirming entrepreneurial competencies and behaviors provide motivational cues that are actionable, independent of self-efficacy development. In contrast, communication understood as non-specific, or understood as the overall level of satisfaction with communication between family members, does not (again) have a direct effect on success - it needs a mediator to do so.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMarcin Staniewski: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Katarzyna Awruk: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Giuseppe Leonardi: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis. Wojciech Słomski: Supervision.

The study was conducted as part of the research project titled Determinants of family entrepreneurial success-mediating role of self-image and achievement motivation (No. 2019/35/B/HS4/02836), funded by the National Science Centre, Poland.