Entrepreneurial activity is a continuous learning process that is rife with uncertainty, and the dialectical interactions arising from knowledge differences and knowledge conflict among individuals on an entrepreneurial team influence team members’ entrepreneurial learning. By reference to fear of failure and entrepreneurial resilience, this study investigates the dual paths by which entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict influences ambidextrous learning to clarify the two sides of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict and to explore the positive influence of fear of failure in this context. The results of empirical tests of a sample of 238 entrepreneurial teams show that (1) entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict positively influences ambidextrous learning; (2) fear of failure plays a significant mediating role in the relationship between entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict and exploratory learning, although its mediating role in the relationship between entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict and exploitative learning is not significant; and (3) entrepreneurial resilience plays a significant mediating role in the relationships between entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict and exploitative learning and between entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict and exploratory learning. The findings of this research explain the mechanism by which entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict affects entrepreneurial learning, expand the field of application of knowledge conflict, enrich the research on knowledge conflict, and provide practical insights that can allow entrepreneurial teams to manage knowledge conflict, eliminate fear of failure, and promote entrepreneurial learning.

The iteration and application of emerging technologies have inaugurated a new wave of entrepreneurship worldwide. However, the global economy has entered an era rife with volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA). In particular, the global economic downturn resulting from the impact of the pandemic has caused the survival environment for new startups to become even less optimistic. Startups that do not cultivate the dynamic ability necessary to adapt to environmental changes in a timely manner will be eliminated in the face of new changes (Kumar et al., 2018; Odlin, 2018; Prashantham & Floyd, 2019). Ambidextrous entrepreneurial learning is key for entrepreneurial teams to increase their knowledge reserves, mitigate resource disadvantages, develop innovative capabilities, capture digital opportunities, and improve business performance (Bao-Shan et al., 2016; Fu et al., 2019; Müller et al., 2019), and it is also a core competitive advantage of startups in a drastically changing environment (Yang et al., 2021, 2022). Only by continuously learning, innovating and maintaining dynamic cognition can entrepreneurial teams enhance their organizational resilience, survive and grow in a complex and changing environment.

The complexity and uncertainty of the VUCA era have caused entrepreneurial teams to pay more attention to the task of recruiting members with diverse knowledge structures. Previous studies have shown that knowledge conflict motivates team members to learn, but little research has examined how knowledge conflicts induce learning patterns in team members. Accordingly, the study introduces entrepreneurial ambidextrous learning, which is the process by which entrepreneurial teams supplement their existing knowledge or create new knowledge and can be divided into exploratory learning (EY) and exploitative learning (EE). Exploratory learning emphasizes the task of seeking new knowledge and new technologies from external sources to help enterprises acquire and maintain new knowledge. Exploitative learning refers to the reintegration of existing knowledge and the adaptation of existing processes to changes in the market and technology (Yang et al., 2012, 2021). Previous studies on entrepreneurial ambidextrous learning have focused mostly on the importance of balancing exploitative learning and exploratory learning to ensure successful entrepreneurship (Fu et al., 2021) as well as the effects of these factors on innovation performance (Deng et al., 2022; Ji, 2019; Nordgren et al., 2010). However, the paths and mechanisms that influence exploratory learning and exploitative learning in complex and volatile contexts have rarely been addressed.

The roles of fear of failure and entrepreneurial resilience in the impact of knowledge conflict on ambidextrous learning among entrepreneurial team members should not be overlooked. Scholars have conducted many helpful explorations of this topic, but the following problems remain unresolved. Previous studies have mostly explored the negative effects of fear of failure and have focused less on the positive effects of fear of failure. Entrepreneurs who experience such fear often increase their alertness, continue learning, increase their efforts to cope with entrepreneurial crises actively (Cacciotti et al., 2016; Mitchell & Shepherd, 2010), and increase their investments in the search for new solutions (Morgan & Sisak, 2016). In addition, previous studies have shown that entrepreneurs with high entrepreneurial resilience are more willing to learn from struggles or setbacks and to continue learning to ensure that they have more resources to deal with challenges (Maija et al., 2021). However, this research has focused mostly on the individual level and has ignored the impact of entrepreneurial resilience at the team level.

In summary, the aim of this study is to investigate the influence of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict (ETKC) on ambidextrous learning and the corresponding mechanism of action. In addition, by testing the mediating roles of entrepreneurial resilience (ER) and fear of failure in this context, this study explores the dual paths through which knowledge conflict influences entrepreneurial learning, clarifies the two sides of knowledge conflict in entrepreneurial teams, and explores the positive influence of fear of failure. The findings of this study enrich the research on entrepreneurial learning and provide practical insights with the aim of enabling entrepreneurial teams to manage knowledge conflict, eliminate fear of failure, and enhance entrepreneurial performance.

Literature reviewEntrepreneurial team knowledge conflictEntrepreneurship is a process in which an entrepreneurial team starts a new business from scratch, which involves the integration of and interaction among multiple elements (Fan & Wang, 2013); therefore, conflict is inevitable in the entrepreneurial process (De Dreu, 2006). Knowledge conflict refers to the differences, collisions, and confrontations that arise among knowledge subjects in terms of their views, opinions, and behavioral patterns as well as to the outcomes of such events resulting from the heterogeneity of knowledge, which correspond to interpersonal conflict and process conflict. Conflict can be either beneficial or detrimental for entrepreneurial teams (de Wit et al., 2011; Diánez-González & Camelo-Ordaz, 2015).

During the entrepreneurial process, team members may have different views for a variety of reasons, thus making it difficult for them to reach a consensus. Conflict within a team may trigger negative emotions (e.g., annoyance, frustration, and irritation) among team members (Jehn & Mannix, 2001), thereby affecting social interactions among members (de Wit et al., 2011), reducing team members’ acceptance of each other, and leading to a decrease in team cohesion, an increase in anxiety, and a lack of confidence (Arazy et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2017; Jehn, 1995), ultimately resulting in team dissolution (Chandler et al., 2005) and entrepreneurial failure.

Although conflict is highly likely to have a negative impact (Jehn, 1995), moderate conflict often influences entrepreneurial behavior in a positive manner (Huang et al., 2022). Such conflict helps enhance competitiveness and instill an entrepreneurial mindset through contact with others in a stimulating learning environment. Moderate conflict is key to effective learning, enhanced creativity, entrepreneurial satisfaction, and good entrepreneurial performance (Chen et al., 2017; Khan et al., 2015), and it contributes to improving the innovative creativity and decision-making of a team (Farh et al., 2010).

Ambidextrous entrepreneurial learningEntrepreneurial learning is a dynamic process through which entrepreneurs acquire knowledge, absorb knowledge, and develop their own skills and abilities through experience, observation, and practice (Cope, 2005). Such learning is an effective way of transforming the information and resources obtained by entrepreneurial teams from the internet into startup performance (Rae, 2005) and is a key source of core innovation advantages for an organization. Entrepreneurial learning is relevant to all entrepreneurial activities. It is an effective way for entrepreneurs to increase their knowledge base, mitigate resource disadvantages, and improve their performance, and it is necessary for entrepreneurs to improve their own capabilities. Only through continuous learning can entrepreneurs effectively address the barriers to receiving information, master the key points of information (Antrettera et al., 2020; Hahn et al., 2017), continually enrich their skills, effectively integrate the resources necessary for entrepreneurship, and rapidly formulate and adjust business development strategies, thereby alleviating the survival crisis faced by startups and laying a solid foundation for the development of subsequent entrepreneurial activities.

By reference to ambidextrous learning theory, this study divides entrepreneurial learning into exploratory learning and exploitative learning on the basis of the way in which knowledge is developed. Specifically, exploratory learning includes search, change, risk-taking, experimentation, gaming, flexibility, discovery, and innovation, i.e., the exploration and acquisition of new knowledge, while exploitative learning includes refinement, screening, production, efficiency, selection, implementation, and execution, i.e., the absorption and utilization of existing knowledge (Yang et al., 2012, 2021).

Fear of failureFear of failure refers to fear resulting from concerns regarding the consequences of potential failure and is often viewed as a psychological factor that inhibits entrepreneurial behavior and serves as a barrier to entrepreneurship (Wagner & Sternberg, 2004). Fear of failure in entrepreneurial contexts is based on the entrepreneur's or entrepreneurial team's cognitive evaluation of the likelihood of failure and their perception of possible entrepreneurial threats in the context of the uncertainty and complexity of entrepreneurship (Cacciotti et al., 2016).

Although fear of failure has received a great deal of attention from entrepreneurship researchers (Cacciotti & Hayton, 2015; Cacciotti et al., 2016), most previous studies have focused on exploring the negative effects of fear of failure on entrepreneurial activities, arguing that fear of failure causes entrepreneurs to develop negative self-perceptions (Stroe et al., 2020), increases their perceptions of threat and risk, decreases their confidence in entrepreneurial success, leads to a low assessment of opportunity value (Grichnik et al., 2010), inhibits entrepreneurial intentions, delays the entrepreneurial action process (Cacciotti et al., 2016), and discourages entrepreneurs from reengaging in entrepreneurial efforts after previous failures. However, recent studies have found that fear of failure can also motivate entrepreneurs to turn their fear of failure into motivation (Holienka et al., 2022), to maintain a constant sense of crisis, and to promote long-term business development. Studies have shown that fear of failure elicits excitement, curiosity, and satisfaction from individuals, which in turn inspire additional entrepreneurial intentions, increase entrepreneurial engagement, serve as motivation for entrepreneurs to continue advancing, promote entrepreneurial effort and entrepreneurial learning, and drive entrepreneurs to seek solutions actively (Cacciotti et al., 2020; Cacciotti et al., 2016).

Studies have explored the factors that influence the fear of failure in terms of both individual entrepreneurs and the external entrepreneurial environment. Individual factors such as gender, level of education, self-efficacy and entrepreneurial passion (Bélanger et al., 2013; Koellinger et al., 2013; Patzelt & Shepherd, 2011; Tsai et al., 2016) and environmental factors such as institutional norms and cultural climate (Chua & Bedford, 2016; Koellinger et al., 2013; Wagner, 2007) have been found to influence the development of fear of failure.

Entrepreneurial resilienceEntrepreneurial resilience is an extension of psychological resilience into the field of entrepreneurship and is a dynamic process of adaptation that supports the ability of entrepreneurs to recover in the face of difficulties and challenges (Korber & McNaughton, 2018). This notion is used to explain why some entrepreneurs are better at coping with the threats and challenges posed by the business environment and achieving entrepreneurial success than others (Bullough et al., 2014; Corner et al., 2017; Duchek, 2018; Fatoki, 2018; Lee & Wang, 2017).

Entrepreneurial resilience differs from organizational resilience in that the former places more emphasis on the mental resilience of the final decision-makers of the firm, such as entrepreneurs, startups, and entrepreneurial teams, while organizational resilience is not limited to this level.

Previous studies have explored entrepreneurial resilience primarily at the individual level, such as by reference to single entrepreneurs and entrepreneurs, arguing that individuals’ cognitive flexibility when coping with changes in internal and external environments and their experience in entrepreneurial crisis situations can enhance entrepreneurial resilience (Duchek, 2018; Purnomo et al., 2021). In turn, such resilience enhances entrepreneurs’ ability to adapt to unstable and constantly changing business environments, withstand internal and external shocks, recover from previous failures, regain entrepreneurial confidence, engage in a higher level of entrepreneurial learning, identify entrepreneurial opportunities, cope with entrepreneurial stress, and reengage in entrepreneurial activities (Cope, 2011; Duchek, 2018; Lafuente et al., 2019; Stephanie, 2018).

Some scholars have also started to focus on entrepreneurial resilience at the team level, and the academic community has widely recognized the positive role played by team resilience in coping with external crises (Alliger et al., 2015; Meneghel et al., 2016; Raetze et al., 2021), arguing that team resilience is an indicator of a team's ability to withstand and adapt to stress (Alliger et al., 2015). However, previous studies have paid insufficient attention to the process by which entrepreneurial team resilience is formed, and studies that have addressed this topic have argued that coordination among team members, the individual resilience of team members, and systematic team reflection are key factors in improving team resilience (Crowe et al., 2017; Gomes et al., 2014).

Research hypotheses and conceptual modelsKnowledge conflict and ambidextrous learning in entrepreneurial teamsKnowledge conflict induced by knowledge heterogeneity among team members plays a positive role in facilitating the acquisition of information and the generation of new knowledge for the team, providing the team with richer and more comprehensive access to knowledge (Leroy et al., 2021; Ye et al., 2021), and stimulating the learning motivation and information-gathering ability of team members with low levels of knowledge (West & Gemmell, 2018; Wu et al., 2015). Moreover, during the entrepreneurial stage, team members are more receptive to knowledge heterogeneity, and knowledge conflicts caused by knowledge heterogeneity are more likely to enhance team members’ entrepreneurial alertness and help them identify and solve problems that require creative thinking (Gao et al., 2019) with the aim of enabling the acquisition of external knowledge through learning and thus facilitating sound strategic decision-making (Khurana, 2021). When knowledge conflict arises in entrepreneurial teams, people begin to question the value of habits and conventional tools, reexamine their thinking from new perspectives, explore new possibilities, reinstate old beliefs, shift and upgrade the focus of knowledge conflict, strengthen dynamic learning, and expand and improve existing knowledge.

On the one hand, knowledge conflict tends to cause the contending parties to confront factors that they have ignored in the past and to encourage team members to learn from existing knowledge. Entrepreneurial teams continue down their original paths to absorb and utilize existing knowledge through refinement, screening, and implementation, which helps them improve and deepen their existing entrepreneurial capacity and technological base, exploit potential resource endowments such as the physical and human resources, skills, customers/markets, and institutional environments utilized by startups, and thus obtain competitive advantage in the market (March, 1991). On the other hand, the generation of knowledge conflict may cause entrepreneurial teams to question existing solutions, and such questioning and the corresponding frustration may lead organizations to engage in exploratory learning with the aim of changing their existing models by searching, risk-taking, experimenting, developing and acquiring new knowledge, launching new products or services, and promoting the optimization of entrepreneurial experience. New elements are added to the original knowledge system of entrepreneurial experience to develop a differentiated business model and avoid familiar traps that are common in the context of entrepreneurship (Ahuja & Lampert, 2001). On this basis, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1: Entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict is positively correlated with ambidextrous entrepreneurial learning.

H1a: Entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict is positively correlated with exploitative learning.

H1b: Entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict is positively correlated with exploratory learning.

Fear of failure refers to fear that results from concerns regarding the consequences of potential failure and is often viewed as a psychological factor that inhibits entrepreneurial behavior and serves as a barrier to entrepreneurship (Wagner & Sternberg, 2004). Fear of failure in the entrepreneurial context is based on an entrepreneur's or entrepreneurial team's cognitive appraisal of the possibility of failure and the team's perception of possible entrepreneurial threats in an uncertain and complex entrepreneurial context. In the entrepreneurial process, because the knowledge backgrounds of different team members include different majors and fields, team members collect and process information in different ways in regard to entrepreneurial activities, which results in differences, conflicts, or collisions within the entrepreneurial team and leads to a sense of ambiguity and uncertainty regarding necessary tasks, evaluation criteria, and required competencies, thus reducing the entrepreneurial self-confidence of team members. As a result, entrepreneurial teams and their members are prone to exhibit a psychological state of fear after assessing the possibility and threat of entrepreneurial failure (Holienka et al., 2022). Accordingly, this study infers that the higher the degree of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict is, the higher the uncertainty generated within a team and the greater the fear that is generated after failure and threat evaluations.

Fear of failure is an important part of the entrepreneurial process and pervades all forms of entrepreneurial activity. In previous studies, fear of failure has been viewed as applicable only to aspiring or very early-stage entrepreneurs and as merely inhibiting their entrepreneurial behavior. In contrast, Cacciotti (2020) distinguished the negative emotional response associated with fear of failure from the resulting behavior and considered the possibility that fear of failure may either stimulate or inhibit behavior (Cacciotti et al., 2020). Fear of failure in entrepreneurial teams is likely to become manifest as a positive response rather than a negative response to difficulties and setbacks in the entrepreneurial process, and it can motivate entrepreneurs to exert more effort, urge them to seek new solutions, and focus their attention on learning (Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2022; Cacciotti et al., 2016; Mcgrath, 2001; Shepherd et al., 2012), thus allowing them to engage in more exploratory learning and exploitative learning.

H2: Fear of failure plays a mediating role in the relationship between entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict and ambidextrous entrepreneurial learning.

H2a: Entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict is positively related with fear of failure.

H2b: Fear of failure is positively related with exploitative learning.

H2c: Fear of failure is positively related with exploratory learning.

Entrepreneurial resilience refers to the ability of team members to anticipate potential threats, respond to unexpected events, and adapt to changes effectively, and it is influenced by organizational structure, team member characteristics, and social networks (Gittell, 2006; Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011). Research has shown that the cognitive flexibility of entrepreneurs positively influences entrepreneurial resilience (Purnomo et al., 2021). However, at present, entrepreneurial subjects mostly take the form of teams, and effective collaboration among team members within an organization and the dynamic diversity of team knowledge structures in the entrepreneurial process are also manifestations of team cognitive flexibility. Knowledge conflict among entrepreneurial team members enables them to view problems from different perspectives and embrace different ways of thinking in a highly uncertain, complex, and dynamic environment, thereby making team members more adaptable with regard to development and change and more likely to solve entrepreneurial problems and mitigate entrepreneurial difficulties.

Entrepreneurial resilience causes entrepreneurs to evaluate the entrepreneurial environment positively, thus helping stimulate positive emotions and allowing individuals to produce positive outcomes by exercising resilience (Maija et al., 2021). Entrepreneurial team members with a high level of entrepreneurial resilience are more likely to adopt a positive attitude in the face of difficulties, can more consciously exert unceasing efforts to engage in entrepreneurial actions in pursuit of established goals and are more willing to learn from difficulties or setbacks and continue to learn (Lafuente et al., 2019), thus allowing them to obtain more resources with which to overcome challenges (Maija et al., 2021). On this basis, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3: Entrepreneurial resilience plays a mediating role in the relationship between entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict and ambidextrous entrepreneurial learning.

H3a: Entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict is positively related with entrepreneurial resilience.

H3b: Entrepreneurial resilience is positively related with exploitative learning.

H3c: Entrepreneurial resilience is positively related with exploratory learning.

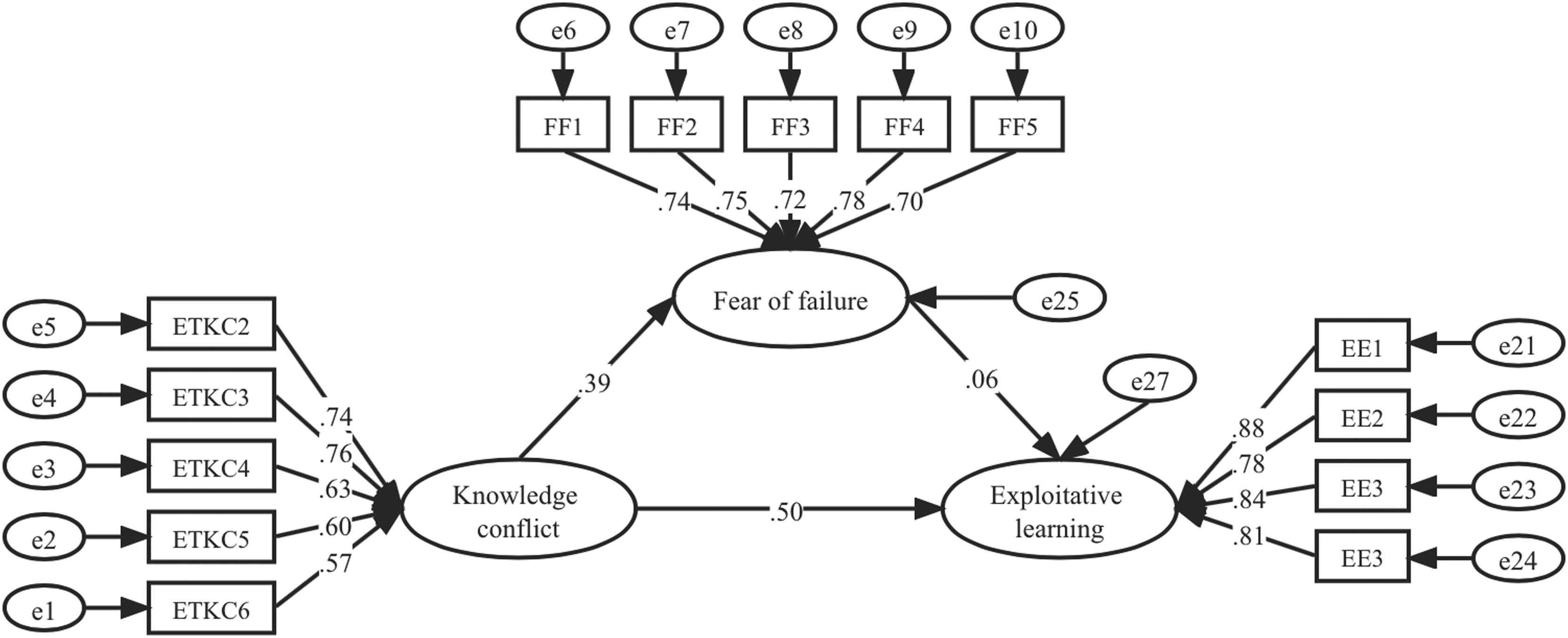

The theoretical model used in this study is shown in Fig. 1.

Study designData collectionThe questionnaires used in the survey were all distributed electronically, and the data were collected from entrepreneurial teams in Fujian, Guangdong, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Tianjin, Beijing and other provinces in China. The researcher first contacted the main person in charge of the companies included in the survey based on personal resources and promised participants that the data obtained through the survey would be used only for academic research. The questionnaire was collected in a voluntary and anonymous manner and included the name of the entrepreneurial enterprise in question (in the form of an optional item). The data collection was strictly confidential. The sample distribution and recovery process took place over a period of more than two months. A total of 270 questionnaires were recovered, and 33 questionnaires featuring missing topic items, completion times of less than 80 s, or the same selection for all items were omitted. The final number of valid questionnaires was 238, for an effective response rate of 88.15%.

Among the participants, 67.2% were male and 32.8% were female, and the percentage of males was higher than that of females. The age distribution of the sample was relatively balanced. The level of education within the sample was generally high; 73.9% of participants had a bachelor's degree or above when starting their business, and their major backgrounds were mainly in economic management and science and technology. A total of 81.5% of the entrepreneurial teams included fewer than 30 people. The entrepreneurial enterprises included in the survey were mostly e-commerce or cultural and creative enterprises. In general, the distribution of the sample with regard to each characteristic was relatively reasonable and representative. The specific statistical characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1.

Statistical characteristics of the sample.

The study conducted by Jehn et al. (2001) on conflict was used as the main reference for entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict. Appropriate adjustments were made to ensure that the selected items aligned with the context of this study, and a total of six items were selected, including “Some of the opinions that trigger team arguments can be expressed in words and language, while others cannot be expressed or are difficult to express and can only be understood (e.g., skills and insights),” “Team members often argue due to differences in their subject matter expertise and knowledge backgrounds,” and “Team members often learn new knowledge, offer new insights, and argue.”

The fear of failure scale used in this research was based on the performance failure appraisal inventory (PFAI) developed by Conroy (2002) by reference to the cognitive appraisal theory of emotion. The simplified five-item version of this scale was used, including items such as “When I fail, I worry about what others think of me” and “When I fail, I worry that I may not be competent enough.”

The entrepreneurial resilience scale was developed by Fatoki (2018). This scale has been empirically tested in both Chinese and Western contexts and has exhibited good reliability and validity. The scale consists of 10 items, including “Able to overcome difficulties to achieve goals,” “Not easily discouraged by failure,” “Able to stay focused under pressure,” and “Returns to good shape as soon as possible after a difficult time.”

The method used to measure ambidextrous entrepreneurial learning was based on March's suggestion to divide entrepreneurial learning into two dimensions: exploitative learning and exploratory learning (March, 1991). Exploitative learning was measured using five items, including “Entrepreneurial teams focus on enhancing the acquisition of knowledge and skills related to existing products” and “Entrepreneurial teams focus on developing the ability to identify solutions to existing customer problems,” while exploratory learning was measured using five items, including “Entrepreneurial teams focus on acquiring new technologies and skills” and “Entrepreneurial teams focus on learning new product development methods and processes in the industry.”

Different genders, age groups, educational backgrounds, and majors can lead to different levels of entrepreneurial learning and fear of failure as well as different entrepreneurial behaviors, and different sizes of entrepreneurial teams may lead to different degrees of knowledge conflict. Therefore, to ensure that the relationships among the variables in this study could be reflected accurately, gender, age, educational background at the time of entrepreneurship, major, entrepreneurial team size, and industry of the startup were included as control variables.

Gender, age, educational background at the time of entrepreneurship, major, entrepreneurial team size, and industry of the startup are all ordered variables. The gender variable is a dummy variable (male=1, female=2). Age was divided into six categories: under 25, 26–30 years old, 31–35 years old, 36–40 years old, 41–45 years old and over 45 years old, which were assigned the numbers 1–6, respectively. Educational background at the time of entrepreneurship was divided into four categories: high school or below, specialized subject, undergraduate, and master's degree or above, which were assigned the numbers 1–4, respectively. Major was divided into eight categories: Literature, History & Philosophy, Economics and Management, Law, Education, Science and Engineering, Agriculture, Medicine, and Other, which were assigned the numbers 1–8, respectively. Entrepreneurial team size was divided into five categories: 1–30, 31–50, 51–100, 101–200, and 201 or above, which were assigned the numbers 1–5, respectively. The industry of the startup was divided into eleven categories: e-commerce, tools and software, healthcare, transportation and travel, social entertainment, biotechnology, energy and environmental protection, intelligent hardware, machinery manufacturing, cultural and creative, and other, which were assigned the numbers 1–11, respectively.

ResultsSample normality testThis paper uses SPSS software to conduct hierarchical regression analysis and Amos software to construct a structural equation model for hypothesis testing and model verification. The sample data should be subject to normal distribution. The results of the normality test are shown in Table 2. The skewness ranges from -1.470 to -0.271, and the absolute value is less than 2.0. Kurtosis ranges from -0.952 to 2.768, with an absolute value of less than 3.0. These findings indicate that the sample data in this paper follow a normal distribution.

Normality test of sample data (N = 238).

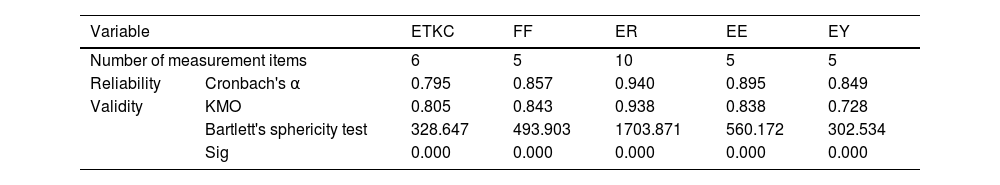

To test the stability, reliability, and consistency of the results of the questionnaire survey, Cronbach's α coefficient is used as a measure of reliability. The Cronbach's α coefficient of each variable, as determined using SPSS 25.0 software, is greater than 0.7, thus indicating that the questionnaire has good reliability. In addition, factor analysis reveals that the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) values for the variables range from 0.65 to 0.90 and that the Sig values for Bartlett's sphericity test are all less than 0.01, thus indicating that the structural validity of the questionnaire is good and that the data can be analyzed using factor analysis. The detailed results are shown in Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis resultsThe results of the Pearson correlation tests are shown in Table 4. All variables are significantly correlated. Entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict is significantly positively correlated with exploitative learning (r=−0.251, p<0.01) and exploratory learning (r=0.431, p<0.01) as well as significantly positively correlated with fear of failure (r=0.319, p<0.01) and entrepreneurial resilience (r=0.314, p<0.01), while fear of failure (r=0.234, p<0.01/r=0.318, p<0.01) and entrepreneurial resilience (r=0.644, p<0.01/r=0.595, p<0.01) are significantly positively correlated with exploitative learning/exploratory learning; hence, the correlations are generally consistent with the hypothesized directions. In addition, the variance inflation factor (VIF) values for the variables range from 1.017 to 2.924, i.e., they do not exceed 3, indicating that there is no multicollinearity among the explanatory variables included in the model.

Means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients of variables.

The main effect of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict on exploitative learning is tested using Amos 26.0. The standardized path coefficient is 0.526, with a p value of 0.000, which is significant at the 0.001 level, thus indicating that the main effect of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict on exploitative learning is significant; hence, Hypothesis H1a is supported. Subsequently, the mediating effects of fear of failure and entrepreneurial resilience on the impact of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict on exploitative learning are tested.

A model of the mediating role of fear of failure in the effect of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict on exploitative learning is constructed, and the goodness-of-fit indexes of the structural equation model are obtained using Amos 26.0. As shown in Table 5, the model has good fit indexes, indicating satisfactory fit. The specific path diagram for the model is shown in Fig. 2. As can be seen from the model parameter estimates shown in Table 6, entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict positively influences fear of failure (β=0.392, p < .001) and exploitative learning (β=0.498, p < .001), but the influence of fear of failure on exploitative learning is not significant (β=0.052, p > .05). Therefore, H2a is supported, but H2b is not supported.

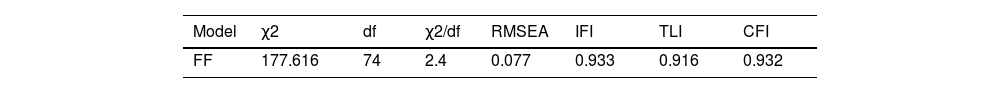

A model of the mediating role of entrepreneurial resilience in the effect of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict on exploitative learning is constructed, and the goodness-of-fit indexes of the structural equation model are obtained using Amos 26.0. As shown in Table 7, the model has good fit indexes, indicating satisfactory fit. The specific path diagram for the model is shown in Fig. 3. The model parameter estimates shown in Table 8 reveal that entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict positively influences entrepreneurial resilience (β=0.385, p < .001) and exploitative learning (β=0.301, p < .001) and that entrepreneurial resilience positively influences exploitative learning (β=0.588, p < .001). As can be seen in Table 8, the influence of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict on exploitative learning decreases from 0.526 to 0.301 under the mediating effect of entrepreneurial resilience, further indicating that entrepreneurial resilience plays a mediating role in the relationship between entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict and exploitative learning. Hence, H3a and H3b are supported.

Finally, an overall model of the influence of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict on exploitative learning is constructed using Amos 26.0. Fit indexes are shown in Table 9, and the path diagram is shown in Fig. 4. As can be seen in Table 10, the standardized path coefficient β for the regression analysis of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict and exploitative learning is 0.268 (P < .001), indicating that entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict significantly positively influences exploitative learning; therefore, Hypothesis 1a is supported. The β for the regression analysis of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict and fear of failure is 0.396 (P < .001), indicating that entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict has a significant positive influence on fear of failure; hence, Hypothesis 2a is supported. The β for the regression analysis of fear of failure and exploitative learning is 0.031 (P > .05); therefore, Hypothesis 2b is not supported. The β for the regression analysis of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict and entrepreneurial resilience is 0.384 (P < .001), indicating that entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict significantly positively influences entrepreneurial resilience; thus, Hypothesis 3a is supported. The β for the regression analysis of entrepreneurial resilience and exploitative learning is 0.588 (P < .001); therefore, Hypothesis 3b is supported.

The main effect of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict on exploratory learning is tested using Amos 26.0. The standardized path coefficient is 0.532 with a p value of 0.000, which is significant at the 0.001 level, thus indicating that the main effect of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict on exploratory learning is significant. Subsequently, the mediating effects of fear of failure and entrepreneurial resilience on the impact of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict on exploratory learning are tested.

A model of the mediating role of fear of failure in the influence of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict on exploitative learning is constructed, and the goodness-of-fit indexes of the structural equation model are calculated using Amos 26.0. As shown in Table 11, the model has good fit indexes, indicating satisfactory fit. The specific path diagram for the model is shown in Fig. 5. The model parameter estimates shown in Table 12 reveal that entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict positively influences fear of failure (β=0.394, p < .001) and exploratory learning (β=0.450, p < .001) and that fear of failure positively influences exploratory learning (β=0.200, p < .01). As can be seen in Table 12, the influence of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict on exploratory learning decreases from 0.532 to 0.450 under the mediating effect of fear of failure, further indicating that fear of failure plays a mediating role in the relationship between entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict and exploratory learning. Hence, H2a and H2c are supported.

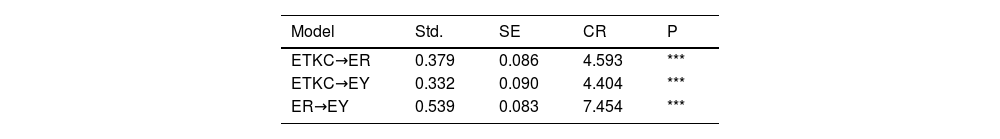

A model of the mediating role of entrepreneurial resilience in the effect of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict on exploratory learning is created, and the goodness-of-fit indexes of the structural equation model are calculated using Amos 26.0. As shown in Table 13, the model has good fit indexes, indicating satisfactory fit. The specific path diagram for the model is shown in Fig. 6. The model parameter estimates in Table 14 reveal that entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict positively influences entrepreneurial resilience (β=0.379, p < .001) and exploratory learning (β=0.332, p < .001) and that entrepreneurial resilience positively influences exploratory learning (β=0.539, p < .001). As can be seen in Table 14, the influence of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict on exploratory learning decreases from 0.532 to 0.332 under the mediating effect of entrepreneurial resilience, further indicating that entrepreneurial resilience plays a mediating role in the relationship between entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict and exploratory learning. Therefore, H3a and H3c are supported.

Finally, an overall model of the influence of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict on exploitative learning is constructed using Amos 26.0. The fit indexes are shown in Table 15. The model has good fit indexes, indicating satisfactory fit, and a path diagram is shown in Fig. 7. As can be seen in Table 16, the standardized path coefficient β for the regression analysis of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict and exploratory learning is 0.267 (P < .001), indicating that entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict significantly positively influences exploitative learning; therefore, Hypothesis 1b is supported. The β for the regression analysis of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict and fear of failure is 0.397 (P < .001), indicating that entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict has a significant positive influence on fear of failure; therefore, Hypothesis 2a is further supported. The β for the regression analysis of fear of failure and exploratory learning is 0.173 (P < .01); therefore, Hypothesis 2c is supported. The β for the regression analysis of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict and entrepreneurial resilience is 0.393 (P < .001), indicating that entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict significantly positively influences entrepreneurial resilience; hence, Hypothesis 3a is further supported. The β for the regression analysis of entrepreneurial resilience and exploratory learning is 0.533 (P < .001); therefore, Hypothesis 3c is supported.

In this study, a dual-path model of the influence of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict on ambidextrous entrepreneurial learning that includes fear of failure and entrepreneurial resilience as mediating variables is constructed, and the results of empirical tests support some of the corresponding hypotheses. The results show that entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict is two-sided; that is, it can both generate fear of failure among members and enhance entrepreneurial resilience within the team. These findings echo the results of previous studies. Previous research has shown that reduced entrepreneurial self-confidence among organizational members promotes the development of fear of failure (Holienka et al., 2022) and that the flexibility of team cognitive structure positively promotes the entrepreneurial resilience of organizations (Purnomo et al., 2021). Therefore, on the one hand, entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict causes communication barriers among members, the intentional dismissal of useful information, and psychological discomfort, thus causing team members to worry about entrepreneurial failure. On the other hand, such conflict is an indicator that team members are diverse in terms of their educational backgrounds, work attitudes, value pursuits, knowledge structures, and intellectual capital, thereby opening up team members’ minds, to a certain extent, to diverse perspectives and enhancing their ability to cope with adversity and crisis and deal with the volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity associated with the VUCA era.

Furthermore, entrepreneurial resilience promotes both exploitative learning and exploratory learning among team members, although fear of failure promotes only exploratory learning. Previous research has shown that both fear of failure and entrepreneurial resilience promote entrepreneurial learning among entrepreneurial team members (Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2022; Lafuente et al., 2019).

The reason for this finding may be that when team members face the fear of failure that is induced by knowledge conflict, their prior knowledge is insufficient to support them in developing solutions that feature more creative thinking, and they use only new knowledge to iterate and upgrade their knowledge system to form high-level cognitions in support of sound strategic decision-making. In other words, when team members are faced with the fear of failure that is induced by knowledge conflict, the exploitative learning associated with refining and integrating previous knowledge can no longer meet the corresponding demand, and only by exploring and absorbing new knowledge can teams overcome the limitations of their original approaches and beliefs and reach a team consensus at a new level.

ImplicationsTheoretical implicationsFirst, the role of knowledge conflict in the entrepreneurial context is explored to identify the mechanism by which entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict influences entrepreneurial learning and to clarify the two sides of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict. Previous studies have focused mostly on the influence of knowledge conflict on innovation performance (Deng et al., 2022; Ji, 2019; Nordgren et al., 2010), but little exploration has been conducted in the entrepreneurial context. In addition, although the research on knowledge conflict has expanded from the individual level to the team and organizational levels and many studies have been conducted to investigate knowledge alliances or R&D teams, little research has focused on entrepreneurial teams. However, in the VUCA era, entrepreneurial subjects mostly take the form of teams, and knowledge conflict among team members is an important factor that influences entrepreneurial success and can either create obstacles to team communication and cause the team to fall apart or equip teams with more diverse knowledge structures and cognitive paradigms (Williams, 2016), thus allowing them to respond to crises more effectively. Therefore, the selection of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict as an antecedent variable affecting entrepreneurial learning and the introduction of fear of failure and entrepreneurial resilience as mediators to construct a dual-path model to explore the double-edged sword effect of entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict is a useful supplement to and expansion of knowledge conflict research. This approach not only expands the research on knowledge conflict in the context of entrepreneurship and enriches the research on knowledge conflict; it also allows us to investigate the important antecedents of entrepreneurial learning in further detail and provides new ideas for related research in the future.

Second, the positive effects of fear of failure are explored from a new perspective. Previous studies have considered fear of failure to be a temporary negative emotional response resulting from entrepreneurs’ cognitive appraisal of the possibility of failure (Cacciotti et al., 2020) and have focused mostly on the negative effects of fear of failure, arguing that fear of failure can serve as a potential psychological barrier for entrepreneurs, thereby reducing individual entrepreneurial confidence, delaying or impeding individual entrepreneurial ideas, and reducing the likelihood of entrepreneurial behaviors. However, in fact, these negative emotional responses to fear of failure are not consistent with the resulting behavior (Cacciotti et al., 2020). Fear of failure may also have positive effects, for example, by stimulating entrepreneurs’ coping effectiveness and entrepreneurial alertness (Hunter et al., 2021), thereby encouraging entrepreneurs to increase their effort and commitment, identify potential opportunities, seek new solutions through learning, and make an effort to search for more market information to enhance their self-efficacy (Marshall et al., 2020). This study explores the positive effects of fear of failure as a mediating variable to explain more effectively why entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict promotes ambidextrous entrepreneurial learning among team members, thereby providing a reference for future research on the positive role of fear of failure in the entrepreneurial process.

Third, the literature on entrepreneurial team resilience is enriched by this study. Previous studies have explored entrepreneurial resilience mostly at the individual level (Bullough et al., 2014; Corner et al., 2017; Duchek, 2018; Fatoki, 2018; Lee & Wang, 2017), and sufficient attention has not been given to the definition of entrepreneurial team resilience and the process by which it is formed. Therefore, the introduction of resilience at the entrepreneurial team level in this study clarifies the formation process of entrepreneurial team resilience and expands the scope of application of resilience theory in the field of entrepreneurship.

Management implicationsIn entrepreneurship, which is closely associated with uncertainty and continuous learning, knowledge conflict among entrepreneurial team members influences entrepreneurial behavior. However, entrepreneurial teams can take certain measures to guide knowledge conflicts along a benign track to help solve the problems and challenges faced by such teams, thereby providing practical insights into the management of knowledge conflict in entrepreneurial teams and the negative effects of fear of failure.

First, knowledge conflict can be transformed into entrepreneurial learning under conditions of active guidance. Maintaining a moderate level of knowledge conflict within an entrepreneurial team can provide that team with new ideas and new thoughts, reduce the team's reliance on its original path, and allow the team to retain its vitality and creativity. In this process, team members are guided to transform knowledge conflict into exploitative learning and exploratory learning, especially exploratory learning, through knowledge sharing, exchange, and feedback with the aim of developing, searching for, and exploring new knowledge, thereby providing an impetus for innovation and the sustainable development of entrepreneurial behavior.

Second, fear of failure can be viewed dialectically. Fear of failure originates from an evaluation of the possibility of and threats associated with potential failure in the context of a particular event in a particular environment; however, fear of failure does not necessarily lead to failure or produce negative effects. Fear is an important evolutionary legacy that stems from evaluations and perceptions, which can be adjusted and changed. Fear of failure may exert a hindering or stimulating effect on entrepreneurial behavior depending on the manner in which an entrepreneurial team and its members respond to fear of failure; therefore, it is especially important to guide team members to confront and actively address fear of failure.

Third, the transformation of knowledge conflict into entrepreneurial resilience can be promoted with the aim of enhancing entrepreneurial resilience. In the process of entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial teams face difficulties and choices and must take risks, and entrepreneurial resilience can prompt them to adopt a positive attitude until their goals are achieved. Therefore, entrepreneurial teams can pay more attention to the role of entrepreneurial resilience and cultivate and enhance their own entrepreneurial resilience through resilience building and development throughout the entrepreneurial process.

Limitations and prospects for future researchFirst, in this study, cross-sectional data were used for the data analysis, and questionnaires were collected during a concentrated period of time. In addition, the responses of the respondents reflected the relationships among the study variables at a certain point in time but failed to illustrate in full detail the dynamic processes operative among knowledge conflict, fear of failure, and ambidextrous entrepreneurial learning within entrepreneurial teams. Therefore, the causal relationships among these variables could not be assessed accurately. In a future study, data can be collected at different time points to identify the relationships among variables more accurately.

Second, the data used in this study were all derived from the self-reports of entrepreneurial team members; such data are superficial and do not accurately reflect deep emotional responses. Therefore, these data may be biased, which may affect the robustness of the findings. More scientific, realistic, and accurate data can be obtained in future research using case studies and in-depth interviews to enhance the persuasiveness of the findings reported herein.

Third, this study treats entrepreneurial team knowledge conflict solely as a unidimensional variable, but knowledge conflict may involve knowledge conflict among founders, among R&D personnel, and between founders and R&D personnel. Therefore, a subsequent study can be conducted to explore the influence of different types of knowledge conflict on ambidextrous entrepreneurial learning.