Infection with the obligate intracellular protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii is asymptomatic in more than 90% of the immunocompetent adult population.1 Cerebral toxoplasmosis (CTx) mainly affects untreated HIV-immunocompromised patients with a CD4+ T cell count <100mm3. It is an extremely rare finding in other patients except for transplant recipients.2,3 Toxoplasmosis after solid organ transplantation is generally diagnosed after the first month post-procedure. It is more frequent in heart transplant recipients and rarely affects kidney transplant recipients.4 We present the case of a patient with cerebral toxoplasmosis 18 years after transplantation.

Clinical caseOur patient was a 74-year-old woman with a history of arterial hypertension, obesity, and severe chronic kidney disease secondary to nephroangiosclerosis and analgesic nephropathy. She underwent transplantation of the right kidney in 1996 and was treated for acute rejection with OKT3. Since then, she has been treated with ciclosporin, prednisone, and mycophenolic acid as immunosuppressants. The patient was assessed by the neurology department due to acute-onset symptoms of dysarthria and right hemiparesis with spontaneous recovery. While hospitalised, she experienced 3 similar episodes that remitted with levetiracetam and increasing the dose of corticosteroids.

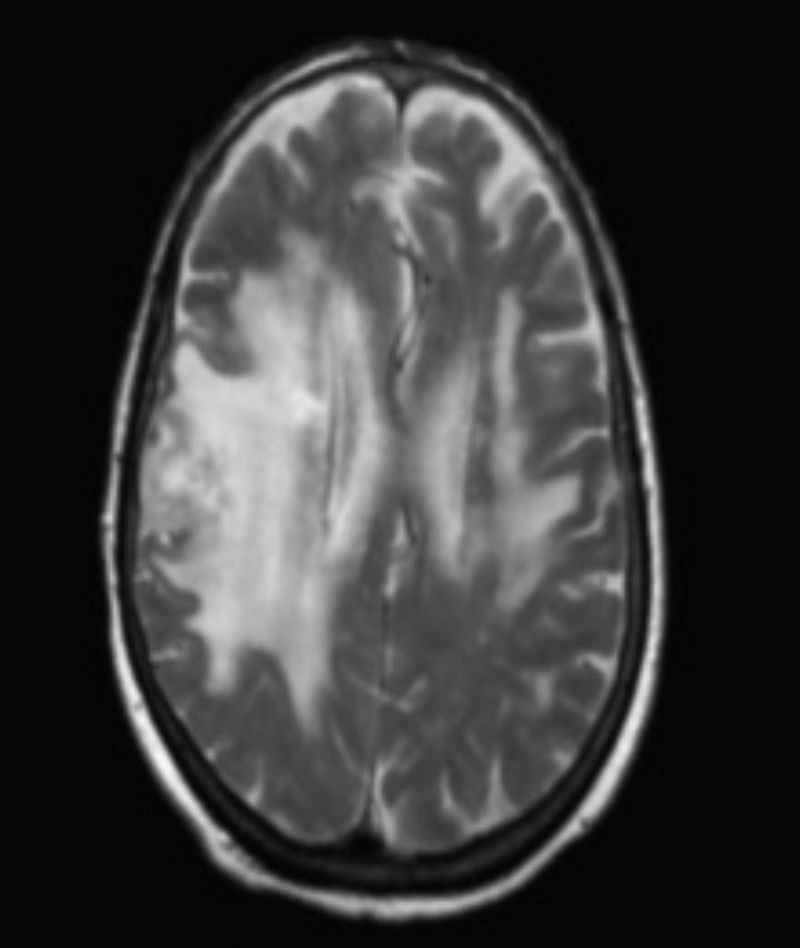

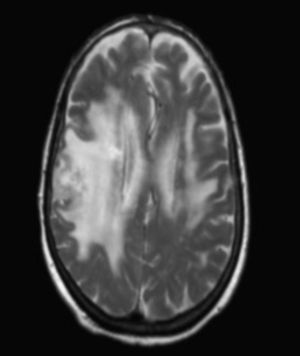

A cranial computed tomography (CT) scan showed diffuse hypodense lesions with effacement of convexity sulci on the right frontal-parietal-temporal area and the left frontoparietal area, as well as multiple subcortical hyperenhanced lesions. A brain MRI showed vasogenic oedema in the subcortical frontoparietal area and left posterior temporal area, plus 3 subcortical nodules (Fig. 1). The electroencephalography revealed no abnormalities. Results for tumour markers and a CT scan of chest, abdomen, and pelvis were normal. The positron emission tomography (PET) revealed that lesions were hypermetabolic and suggestive of malignancy.

A brain biopsy was performed. The first histopathological study yielded non-specific results consisting of presence of lymphoproliferative infiltrate. We requested a second assessment of the same sample, which revealed trophozoites; we diagnosed CTx. The PCR test for T. gondii was positive.

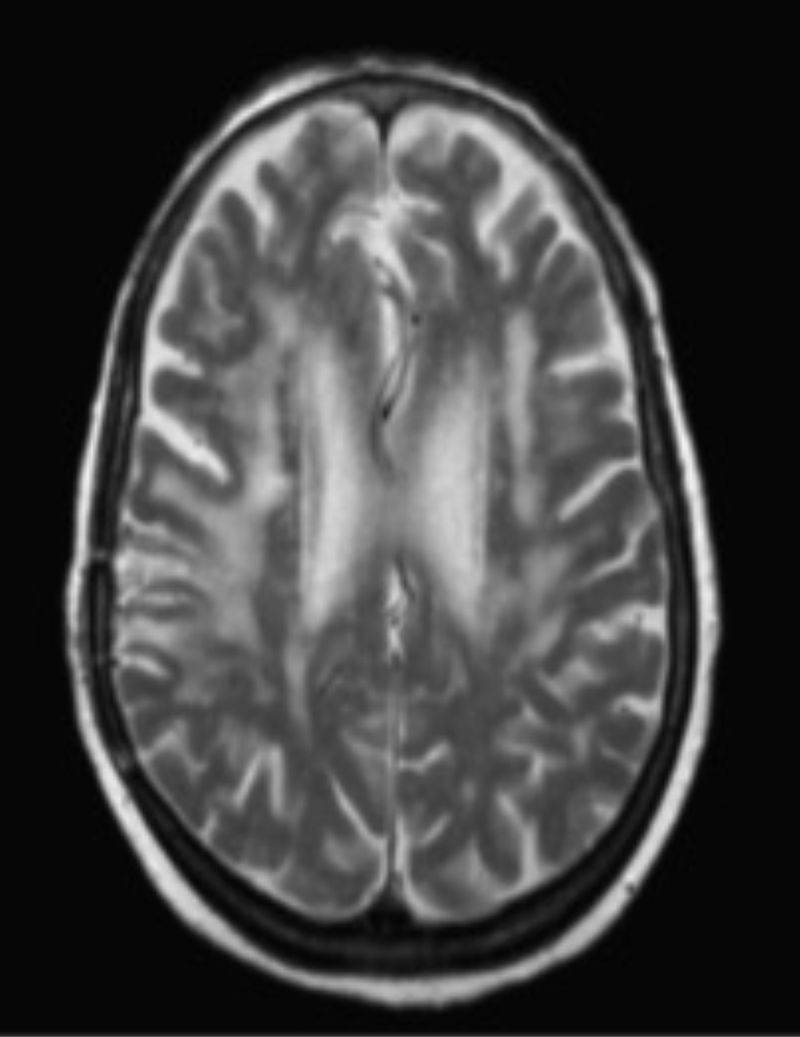

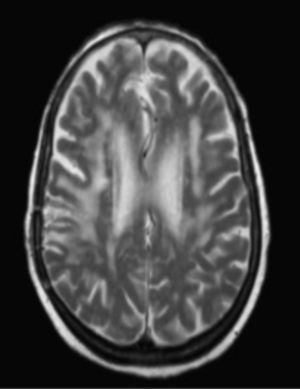

The patient showed good clinical and radiological progress (Fig. 2) after starting treatment with pyrimethamine and clindamycin.

DiscussionWe described the case of a non-HIV immunocompromised patient in whom cerebral toxoplasmosis was diagnosed and treated specifically 18 years after she had undergone a kidney transplantation.

Neurological complications due to toxoplasmosis are rare in solid organ recipients, and even more so in kidney transplantation patients. The literature describes 35 cases.4,5,7,8

Infection with T. gondii in solid organ transplantation patients results in high mortality rates. In a report of 6 cases of toxoplasmosis following kidney transplantation, the mortality rate amounted to 65.5%, whereas neurological complications were less frequent.5 Symptom onset after transplantation ranges from the first to the fourth month, but there is also late variants which are exceptionally rare.6,7 Our patient showed her first neurological symptoms 18 years after the transplantation, and no changes had been made to her immunosuppressant treatment; therefore, late presentation of CTx may be possible in these patients.

Diagnosing toxoplasmosis in non-HIV immunocompromised patients might be difficult; in fact, 30% of these diagnoses are established by autopsy.7 In an immunocompromised kidney transplant recipient with brain lesions, the main aetiological options to be assessed are infection and neoplasm. The microbes to be considered are Aspergillus, Nocardia, Cryptococcus, Listeria, Tuberculosis, and Toxoplasma. Primary cerebral lymphoma (PCL) is the most frequent of the neoplastic aetiologies.9 It is often difficult to distinguish between one entity or the other using only radiological findings, and even more challenging in immunocompromised patients who may display PCL as multiple lesions.7,9 Certain radiological characteristics may help us differentiate them10; however, biopsies are generally necessary to determine the aetiology of the lesions histologically. In our case, the first histological study suggested PCL, and it was not until the second study that the trophozoites were detected.

Positive PET findings are thought to suggest a neoplastic aetiology; however, there are no conclusive studies on the effectiveness of this technique in patients with CTx.11 A previous case of positive PET findings in a patient with CTx has also been described,12 but the usefulness of this test for distinguishing between PCL and CTx is questionable.

No empirical treatments for toxoplasmosis were started, as would be done with HIV patients, since toxoplasmosis was not initially considered due to the time elapsed (more than 15 years since transplantation).

ConclusionFirstly, we must underscore that CTx may manifest late in patients with kidney transplants; and secondly, this entity must be included in the differential diagnosis of brain lesions in transplant patients, although the main diagnostic alternative is PCL. Thirdly and fundamentally, an accurate study of the anatomical pathology findings is necessary since the prognosis can change drastically and become favourable.

FundingThe authors have received no funding for this study.

Please cite this article as: Morollón N, Rodríguez F, Duarte J, Sánchez R, Camacho FI, Campo E. Lesiones cerebrales en trasplante renal de larga evolución, ¿linfoma cerebral primario vs. toxoplasmosis cerebral?. Neurología. 2017;32:268–270.

This study was presented in poster format at the 66th Annual Meeting of the Spanish Society of Neurology.