Functional movement disorder (FMD), a type of functional neurological disorder, is a common reason for consultation with the neurology department. The efficacy of physiotherapy for motor rehabilitation of these patients has been widely studied. The aim of this review is to analyse the available evidence on the effects of physiotherapy on motor symptoms, activity (gait, mobility, balance), perceived health, quality of life, and the cognitive/emotional state of patients with FMD.

MethodsThis review follows the PRISMA recommendations. Four electronic databases were searched for relevant articles. Our review included randomised controlled trials investigating the effects of a specialised physiotherapy intervention alone or in combination with other therapies as part of a multidisciplinary approach, with results compared against standard physiotherapy.

ResultsWe reviewed 4 studies, including a total of 188 patients. We gathered data on the study population, outcome measures, protocols, and results. According to the Oxford quality scoring system, 3 studies had moderate methodological quality (3–4/5) and the remaining study presented poor methodological quality (< 3).

ConclusionsPhysiotherapy improves motor symptoms, activity, perceived health, and quality of life in patients with FMD.

El trastorno del movimiento funcional (TMF) se engloba dentro de los trastornos neurológicos funcionales (TNF). Este constituye un motivo de consulta habitual en el ámbito de la neurología. La eficacia del tratamiento de fisioterapia en la rehabilitación motora de estos pacientes es un campo ampliamente estudiado. El objetivo de esta revisión es analizar la evidencia científica existente sobre los efectos del tratamiento fisioterápico en las manifestaciones motoras, la actividad (marcha, movilidad, equilibrio), la percepción de salud, la calidad de vida o el estado cognitivo-emocional de las personas con TMF.

MétodosEsta revisión se llevó a cabo siguiendo las recomendaciones de la declaración PRISMA. Se realizaron búsquedas sistemáticas en 4 bases de datos electrónicas para localizar resultados pertinentes. Se incluyeron ensayos controlados aleatorizados que investigasen los efectos de una intervención de fisioterapia especializada, de manera aislada o combinada con otras terapias dentro de un marco multidisciplinar; comparando su aplicación con el tratamiento fisioterápico estándar.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 4 estudios con un total de 188 sujetos. Se extrajeron datos sobre la población, las medidas de resultado, los protocolos y los resultados. Se aplicó el sistema de puntuación de calidad de Oxford, obteniéndose 3 estudios con una calidad metodológica moderada (3-4/5) y un estudio con calidad metodológica baja (<3).

ConclusionesEl tratamiento de fisioterapia en personas diagnosticadas con TMF genera cambios positivos en su sintomatología motora, actividad, percepción de salud y calidad de vida.

Functional neurologic disorder (FND) lies between the fields of neurology and psychiatry and is a frequent reason for consultation with outpatient neurology and neuropsychiatry consultations.1 Over the past 20 years, specialists have taken a “mind–brain” approach, according to which neurology and psychiatry complement one another in the diagnosis and treatment of this condition.2,3

FND is a disorder of the voluntary or somatic nervous system causing a wide range of symptoms, including paralysis, tremor, dystonia, sensory alterations, speech alterations, and seizures. Patients with FND present positive clinical symptoms, which are not correlated with a pathophysiological cause.4 The term “functional,” replacing the former term “psychogenic,” is more neutral in its reference to the aetiology of the condition, improving understanding and acceptance by patients.5 To achieve adequate communication, it is vital that diagnostic labels are useful and are accepted by physicians and patients alike.6

Additional changes to the definition of FND were introduced in the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). In this latest edition of the DSM, diagnosis of FND is based on the positive identification of physical symptoms that are not correlated with neurological disease; psychiatric comorbidities are not a necessary condition for diagnosis. Diagnosis of FND does not exclude other conditions.7

From an epidemiological viewpoint, FND is one of the most frequent causes of neurological disability. It has an incidence of 4–12 cases per 100 000 person-years.8,9

In a study published in 2018, Espay et al.,10 established several types of FND: motor FND, FND with sensory manifestations, axial FND (disorders of gait and posture), speech FND, and paroxysmal FND. Within the spectrum of motor FNDs, the term functional movement disorder (FMD) is used in reference to such symptoms as weakness, paralysis, tremor, and dystonia, which are not caused by a typical neurological disease. FMD is generally associated with a high degree of disability and poor prognosis, and has a great economic burden.11–13

Clinical features suggestive of FMD include sudden disease onset, disappearance of symptoms with distraction and exacerbation with attention, and excessive fatigue. Diagnosis is based on detection during the neurological examination of typical features of FMD that are incongruous with an organic disorder and inconsistent over time and between tasks.14

Several sets of diagnostic criteria have been proposed, but they present low inter-rater reliability when applied to movement disorders with nonspecific symptoms.15 Among the most widely used criteria, we should mention those proposed by Gupta and Lang,16 who introduce the diagnostic category of laboratory-supported definite FMD based on electrophysiological findings of psychogenic myoclonus; the authors use electromyography and electroencephalography to evaluate premovement potentials and psychogenic tremor. These criteria have recently been updated by Espay et al.14

In recent years, neuroimaging studies have revealed alterations in brain network function and metabolic demands during task execution.17 Furthermore, in patients with FMD, abnormal differential weighting of ascending and descending sensory data leads to prediction errors about sensory data, which, together with body-focused attention, generates abnormal perceptions or movements.18

Another differential feature of these patients is a reduced sense of agency, a process of retrospective assessment of an action and its expected and actual sensory outcomes.19 In this sense, patients with FMD perceive their movements, or lack thereof, as involuntary. Furthermore, several major predisposing and reinforcing factors have been described.20

Prognosis of FMD is usually poor due to under-recognition of this condition among healthcare professionals. Another relevant factor is health status before treatment. It is widely known that long-standing symptoms are associated with poor prognosis, whereas young age and early diagnosis are indicators of favourable prognosis.10

There is growing evidence of the effectiveness of physical therapy (movement retraining) and cognitive-behavioural therapy.21,22

In 2013, Nielsen et al.22 published a systematic review of physical therapy interventions for the management of functional motor symptoms. Despite its great value, the study has several methodological limitations. Firstly, the studies reviewed presented significant methodological differences: except for one retrospective, controlled study,23 all studies were case reports or case series, and no prospective study was included. Secondly, none of the studies was randomised, and most included small samples (only 7 of the 29 studies included samples of more than 10 patients). Lastly, most of the studies were performed in hospital settings; therefore, their results cannot be extrapolated to the outpatient setting.

In the light of the above, we conducted a systematic literature search of studies published after the publication of the review by Nielsen et al.22

The purpose of this study is to analyse the available evidence on the effects of physical therapy on motor symptoms, activity (gait, mobility, balance), perceived health status, quality of life, and cognitive and emotional status in patients with FMD.

Material and methodsDatabases and search strategyIn March 2021, we consulted the following databases: Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and the BRAIN resource search engine of Universidad Rey Juan Carlos (Madrid). The following keywords were used: “physical therapy,” “physiotherapy,” “rehabilitation,” “functional movement disorders,” “functional motor symptoms,” and “psychogenic motor symptoms,” combined with the Boolean operator AND (Table 1). We considered protocols published in registries and manually searched the references cited in the studies gathered in our literature search to identify relevant studies.

Eligibility criteriaWe established the following inclusion criteria:

- •

Study type: randomised, controlled trials written in English or Spanish and published since 2013

- •

Participants: studies including patients with a diagnosis of FMD

- •

Type of intervention: studies analysing the effect of specialised physical therapy interventions, alone or combined with other therapies in a multidisciplinary approach, and comparing the effects of a specialised physical therapy intervention against those of standard physical therapy

- •

Outcome measures: studies evaluating changes in motor symptoms, activity (gait, mobility, balance), perceived health status, quality of life, or cognitive or emotional status.

We excluded articles whose design was incomplete or that did not describe the outcome of the intervention, as well as those including heterogeneous samples or patients with different types of FND.

Study selection and data extractionWe gathered data on the sample included in each study, applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria, gathered outcome measures, described interventions, and collected data on the outcome of the intervention. One of the authors of this study reviewed the titles and abstracts to determine whether the articles gathered met the inclusion criteria. The full texts of articles potentially meeting all inclusion criteria was examined in greater detail. The final selection of studies was performed by the author and another researcher.

Evaluation of methodological quality and risk of biasThe Oxford Quality Scoring System24 was used to assess the methodological quality and objectiveness of the studies included: scores < 3 indicate poor methodological quality, scores of 3–4 indicate moderate methodological quality, and a score of 5 indicates high methodological quality.

To evaluate the risk of bias of each trial, we used the Cochrane risk of bias tool, which assesses random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other potential sources of bias. Each domain is rated as presenting low, high, or unclear risk of bias. The literature review was conducted following the recommendations of the PRISMA statement.25 Methodological quality and risk of bias were evaluated by the lead author.

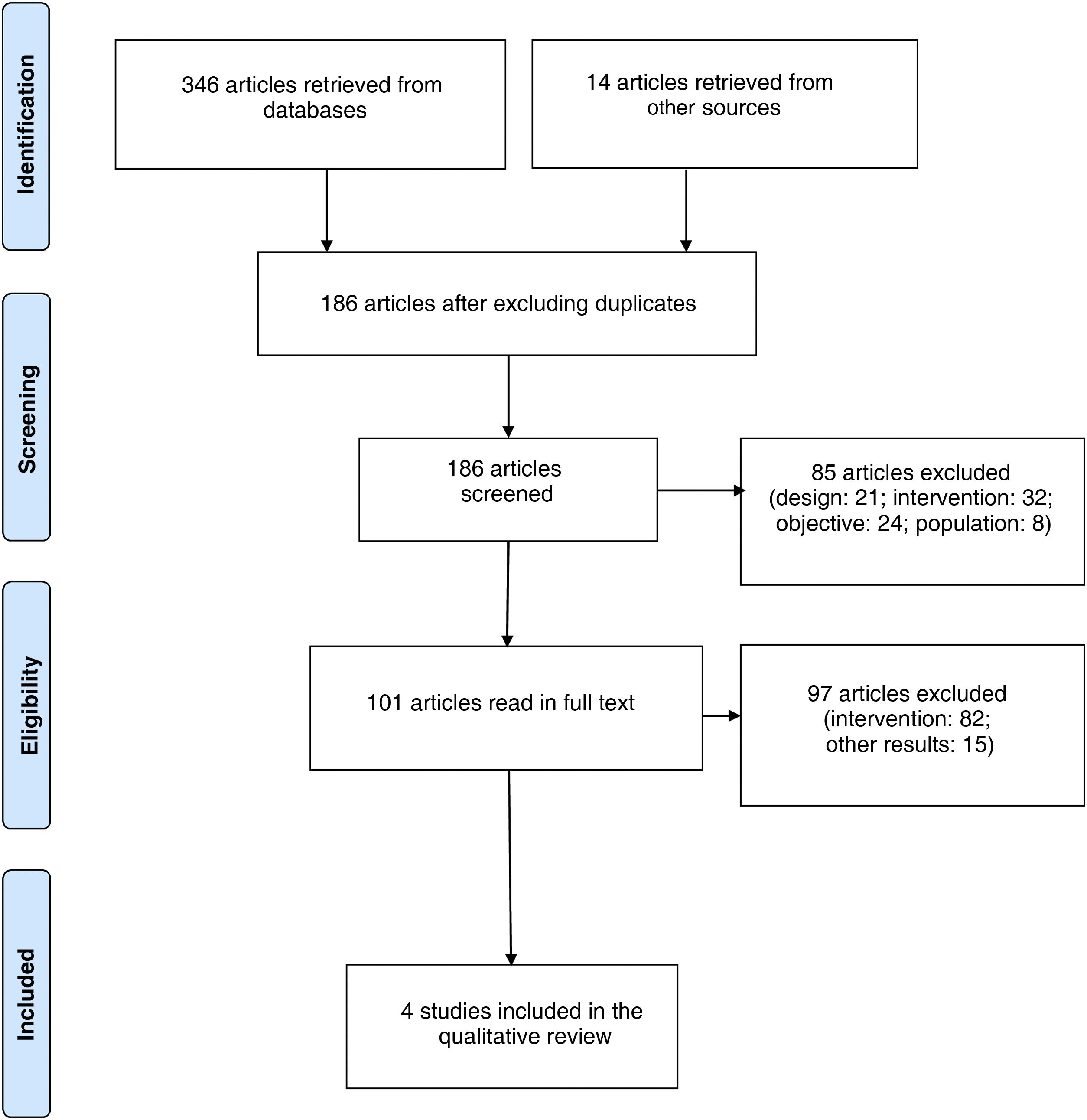

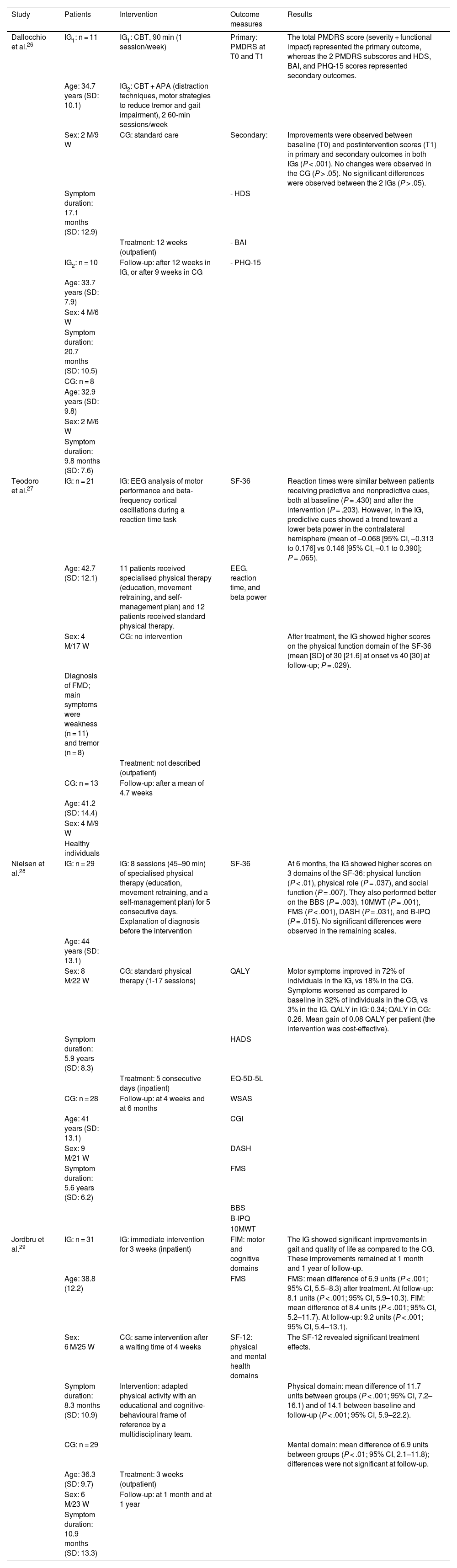

ResultsStudy selectionA total of 360 articles were retrieved; after excluding duplicate articles, 186 original articles were included for review. We read the abstracts of potentially eligible articles to determine whether they were relevant for our review and met the inclusion criteria. We finally included 4 studies,26–29 reporting data from a total of 188 participants. The study selection process is described in the flow chart in Fig. 1.

Study characteristics and synthesis of resultsAll 4 studies used physical therapy as part of the therapeutic intervention. Two studies applied a specialised education-based physical therapy programme, movement retraining (to restore normal function redirecting the attentional focus), and self-management plan using a workbook.27,28 One study proposed combining physical therapy with cognitive-behavioural therapy using distraction techniques, motor strategies to reduce tremor, and low/moderate-intensity walking.26 The remaining study developed a programme of adapted physical activity within a multidisciplinary cognitive-behavioural framework (the 3 main elements of the intervention were explaining symptoms, positively reinforcing normal function, and not positively reinforcing dysfunction).29

Control groups generally received standard medical care26 or standard physical therapy.28 In one of the studies, the control group did not receive physical therapy,27 and in the remaining study, controls received the same treatment as the intervention group but started 4 weeks later.29

In 2 studies, the intervention took place on an outpatient basis,26,27 whereas the remaining 2 studies used inpatient programmes.28,29

Session duration ranged from 45 to 90 minutes per day26–28; this information is not reported in the study by Jordbru et al.29 The duration of the intervention varied greatly: in one study,28 participants underwent intensive treatment for 5 consecutive days; in another,29 the intervention lasted 3 weeks; another study26 designed a 12-week intervention (2 weekly sessions); whereas in the study by Teodoro et al.,27 the duration of the intervention is not specified.

In all studies, participants were followed up after the intervention; follow-up time ranged from 4 weeks to one year. In 2 studies,26,27 participants attended a single follow-up consultation, whereas in the remaining 2,28,29 they were assessed at 2 different time points: one at 1/3 months postintervention and the second at 6/12 months postintervention.

According to the results of these studies, physical therapy improves motor symptoms, activity, quality of life, and perceived health status.

Motor symptoms and activityOutcome measures evaluating motor function varied between studies. Teodoro et al.27 used surface electroencephalography to analyse motor performance, reaction time, and beta-frequency cortical oscillations during reaction time tasks with predictive and nonpredictive cues. They found that reaction times did not improve in patients with FMD when the cue was predictive of the upcoming movement. These patients displayed persistent beta synchronisation and lack of lateralised beta desynchronisation during motor preparation; this is explained by the abnormal explicit movement control observed in these patients as a result of excessive self-directed attention. This points to impaired motor performance, as event-related beta desynchronisation indicates movement preplanning and preparation.

After the intervention, Nielsen et al.28 observed improved performance in the Berg Balance Scale; Timed 10-Meter Walk Test; Functional Mobility Scale; Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand questionnaire; and Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire. Perception of motor symptoms improved in 72% of patients in the intervention group, as compared to only 18% in the control group.

Jordbru et al.29 reported significant improvements in gait and functional independence, as measured with the Functional Mobility Scale and the Functional Independence Measure. These improvements remained at one month and one year of follow-up.

Quality of life and perceived health statusAfter the physical therapy programme, Teodoro et al.27 observed higher scores on the physical function domain of the Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36). Similarly, Nielsen et al.28 observed significant increases in 3 domains of the SF-36: physical function, physical role, and social function.

Jordbru et al.29 reported significant improvements in the physical and mental domains of the SF-12 after treatment. However, at the follow-up consultation, these improvements remained significant only in the physical domain.

In the study by Dallocchio et al.,26 controls displayed improvements in the severity and functional impact subscales of the Psychogenic Movement Disorders Rating Scale after treatment.

Cognitive and emotional statusSeveral studies evaluated depression and anxiety. Nielsen et al.28 used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, finding no significant differences between groups. In the study by Dallocchio et al.,26 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and Beck Anxiety Inventory scores were used as secondary outcome measures.

Study characteristics are summarised in Table 2.

Summary of results.

| Study | Patients | Intervention | Outcome measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dallocchio et al.26 | IG1: n = 11 | IG1: CBT, 90 min (1 session/week) | Primary: PMDRS at T0 and T1 | The total PMDRS score (severity + functional impact) represented the primary outcome, whereas the 2 PMDRS subscores and HDS, BAI, and PHQ-15 scores represented secondary outcomes. |

| Age: 34.7 years (SD: 10.1) | IG2: CBT + APA (distraction techniques, motor strategies to reduce tremor and gait impairment), 2 60-min sessions/week | |||

| Sex: 2 M/9 W | CG: standard care | Secondary: | Improvements were observed between baseline (T0) and postintervention scores (T1) in primary and secondary outcomes in both IGs (P < .001). No changes were observed in the CG (P > .05). No significant differences were observed between the 2 IGs (P > .05). | |

| Symptom duration: 17.1 months (SD: 12.9) | - HDS | |||

| Treatment: 12 weeks (outpatient) | - BAI | |||

| IG2: n = 10 | Follow-up: after 12 weeks in IG, or after 9 weeks in CG | - PHQ-15 | ||

| Age: 33.7 years (SD: 7.9) | ||||

| Sex: 4 M/6 W | ||||

| Symptom duration: 20.7 months (SD: 10.5) | ||||

| CG: n = 8 | ||||

| Age: 32.9 years (SD: 9.8) | ||||

| Sex: 2 M/6 W | ||||

| Symptom duration: 9.8 months (SD: 7.6) | ||||

| Teodoro et al.27 | IG: n = 21 | IG: EEG analysis of motor performance and beta-frequency cortical oscillations during a reaction time task | SF-36 | Reaction times were similar between patients receiving predictive and nonpredictive cues, both at baseline (P = .430) and after the intervention (P = .203). However, in the IG, predictive cues showed a trend toward a lower beta power in the contralateral hemisphere (mean of –0.068 [95% CI, –0.313 to 0.176] vs 0.146 [95% CI, –0.1 to 0.390]; P = .065). |

| Age: 42.7 (SD: 12.1) | 11 patients received specialised physical therapy (education, movement retraining, and self-management plan) and 12 patients received standard physical therapy. | EEG, reaction time, and beta power | ||

| Sex: 4 M/17 W | CG: no intervention | After treatment, the IG showed higher scores on the physical function domain of the SF-36 (mean [SD] of 30 [21.6] at onset vs 40 [30] at follow-up; P = .029). | ||

| Diagnosis of FMD; main symptoms were weakness (n = 11) and tremor (n = 8) | ||||

| Treatment: not described (outpatient) | ||||

| CG: n = 13 | Follow-up: after a mean of 4.7 weeks | |||

| Age: 41.2 (SD: 14.4) | ||||

| Sex: 4 M/9 W | ||||

| Healthy individuals | ||||

| Nielsen et al.28 | IG: n = 29 | IG: 8 sessions (45–90 min) of specialised physical therapy (education, movement retraining, and a self-management plan) for 5 consecutive days. Explanation of diagnosis before the intervention | SF-36 | At 6 months, the IG showed higher scores on 3 domains of the SF-36: physical function (P < .01), physical role (P = .037), and social function (P = .007). They also performed better on the BBS (P = .003), 10MWT (P = .001), FMS (P < .001), DASH (P = .031), and B-IPQ (P = .015). No significant differences were observed in the remaining scales. |

| Age: 44 years (SD: 13.1) | ||||

| Sex: 8 M/22 W | CG: standard physical therapy (1-17 sessions) | QALY | Motor symptoms improved in 72% of individuals in the IG, vs 18% in the CG. Symptoms worsened as compared to baseline in 32% of individuals in the CG, vs 3% in the IG. QALY in IG: 0.34; QALY in CG: 0.26. Mean gain of 0.08 QALY per patient (the intervention was cost-effective). | |

| Symptom duration: 5.9 years (SD: 8.3) | HADS | |||

| Treatment: 5 consecutive days (inpatient) | EQ-5D-5L | |||

| CG: n = 28 | Follow-up: at 4 weeks and at 6 months | WSAS | ||

| Age: 41 years (SD: 13.1) | CGI | |||

| Sex: 9 M/21 W | DASH | |||

| Symptom duration: 5.6 years (SD: 6.2) | FMS | |||

| BBS | ||||

| B-IPQ | ||||

| 10MWT | ||||

| Jordbru et al.29 | IG: n = 31 | IG: immediate intervention for 3 weeks (inpatient) | FIM: motor and cognitive domains | The IG showed significant improvements in gait and quality of life as compared to the CG. These improvements remained at 1 month and 1 year of follow-up. |

| Age: 38.8 (12.2) | FMS | FMS: mean difference of 6.9 units (P < .001; 95% CI, 5.5–8.3) after treatment. At follow-up: 8.1 units (P < .001; 95% CI, 5.9–10.3). FIM: mean difference of 8.4 units (P < .001; 95% CI, 5.2–11.7). At follow-up: 9.2 units (P < .001; 95% CI, 5.4–13.1). | ||

| Sex: 6 M/25 W | CG: same intervention after a waiting time of 4 weeks | SF-12: physical and mental health domains | The SF-12 revealed significant treatment effects. | |

| Symptom duration: 8.3 months (SD: 10.9) | Intervention: adapted physical activity with an educational and cognitive-behavioural frame of reference by a multidisciplinary team. | Physical domain: mean difference of 11.7 units between groups (P < .001; 95% CI, 7.2–16.1) and of 14.1 between baseline and follow-up (P < .001; 95% CI, 5.9–22.2). | ||

| CG: n = 29 | Mental domain: mean difference of 6.9 units between groups (P < .01; 95% CI, 2.1–11.8); differences were not significant at follow-up. | |||

| Age: 36.3 (SD: 9.7) | Treatment: 3 weeks (outpatient) | |||

| Sex: 6 M/23 W | Follow-up: at 1 month and at 1 year | |||

| Symptom duration: 10.9 months (SD: 13.3) |

10MWT: Timed 10-Meter Walk Test; APA: adjunctive physical therapy; BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory; BBS: Berg Balance Scale; B-IPQ: Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire; CBT: cognitive-behavioural therapy; CGI: Clinical Global Impression scale; DASH: Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaire; EEG: electroencephalography; EQ-5D-5L: European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 5 Level version; FIM: Functional Independence Measure; FMS: Functional Mobility Scale; CG: control group; IG: intervention group; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HDS: Hamilton Depression Scale; M: men; PHQ-15: Patient Health Questionnaire-15; PMDRS: Psychogenic Movement Disorders Rating Scale; QALY: quality-adjusted life year; SD: standard deviation; SF-12: 12-Item Short Form Survey; SF-36: Short Form-36 Health Survey; FMD: functional movement disorder; W: women; WSAS: Work and Social Adjustment Scale.

According to the Oxford Quality Scoring System, 3 studies presented moderate to high methodological quality26,28,29 and one presented poor methodological quality.27 Given the nature of the intervention, participants were not blind to the treatment in any study; neither were the raters, in some cases.

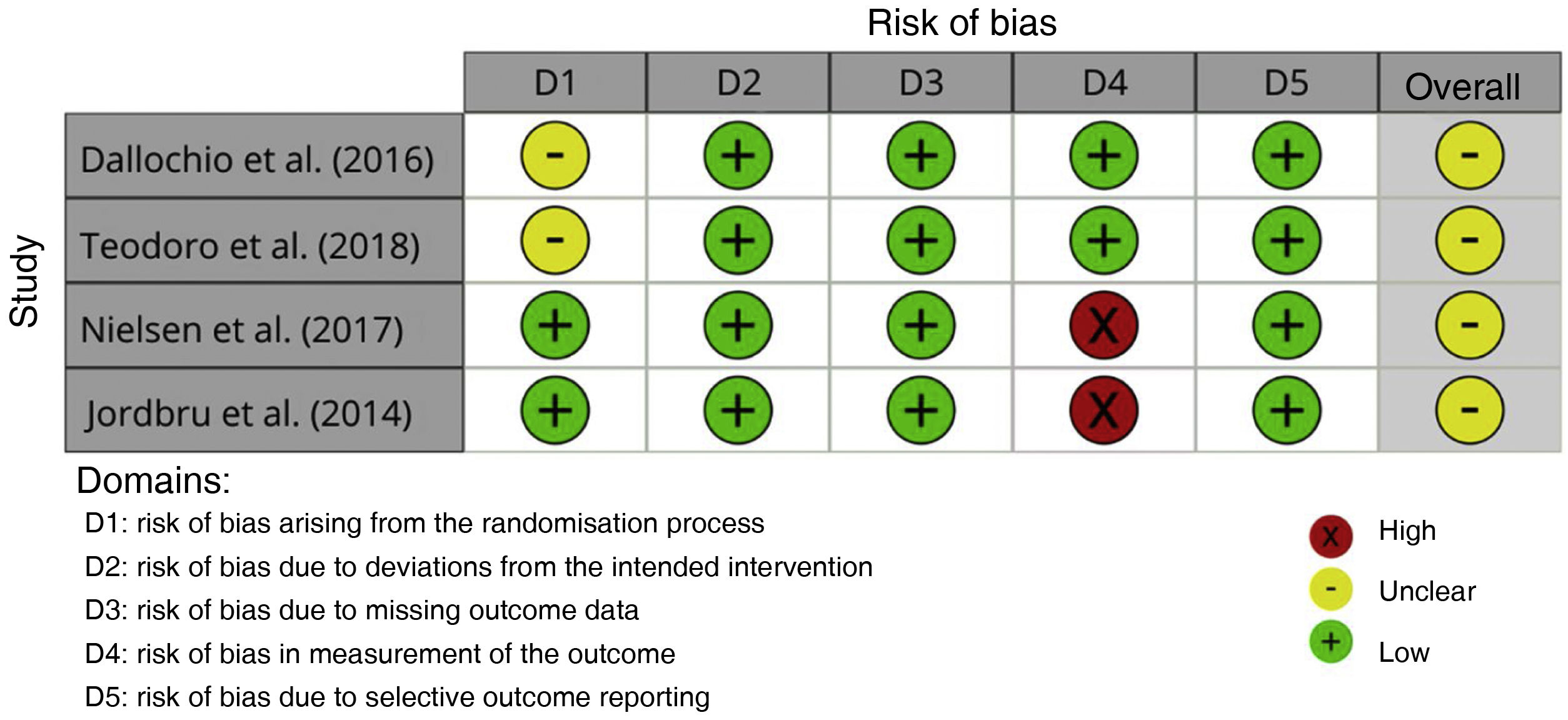

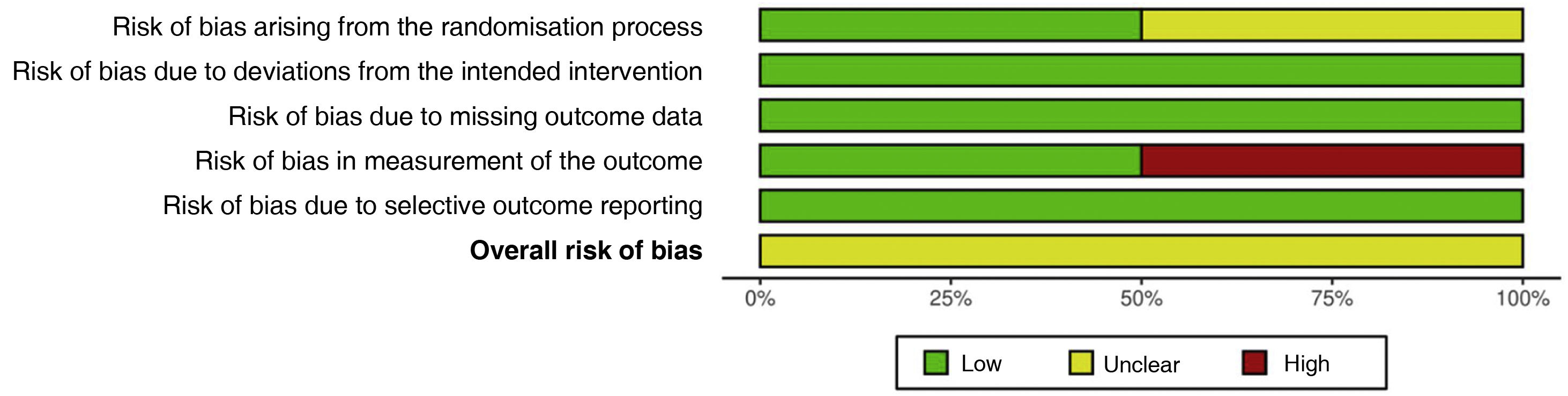

Assessment of risk of biasTwo studies26,27 presented an unclear risk of bias arising from the randomisation process; risk of bias was low in the remaining 2. All studies presented a low risk of bias due to deviations from the intended interventions. All studies presented a low risk of bias due to missing outcome data. Two studies28,29 presented a high risk of bias in measurement of the outcome; risk of bias was low in the remaining 2. Risk of bias due to selective outcome reporting was low in all 4 studies. Overall risk of bias was unclear in all studies (Figs. 2 and 3).

DiscussionIn recent years, there has been growing clinical and research interest in FMD; this can be seen in the large number of studies on the topic published in the last decade. FMD may be identified with the current diagnostic criteria; however, diagnosis is not based on exclusion.16 Much remains to be known about the pathophysiological and neurobiological causes of the disorder.10

Neuroimaging has played a pivotal role in identifying and reshaping our understanding of FMD.17,18,30 These studies have identified structural and functional abnormalities in the central nervous system that involve hypoactivation of cortical and subcortical motor pathways, as well as increased modulation by the limbic system. Neurobiological theories point to impaired regulation of motor movement and abnormal emotional processing in these patients.

There is broad consensus that treatment for FMD should be provided by specialised multidisciplinary units. Treatment focuses on retraining activity, with physiotherapists playing an essential role. According to the paradigm of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), patients are diagnosed based on the presence of certain deficits; however, specific tools must subsequently be used to evaluate activity limitation and participation restriction.31

This review analyses the most recent scientific evidence on physical therapy for FMD. Treatment must be multidisciplinary, aiming to educate patients about their disease, achieve motor retraining, and provide self-care strategies. Specialised physical therapy programmes improve motor symptoms and activity, which in turn improves perceived health status and quality of life.

All the studies included in our review analysed specialised physical therapy interventions. Only one combined physical therapy with cognitive-behavioural therapy.26 As mentioned previously, physical therapy is based on 3 pillars: education, movement retraining, and a self-management plan. Education is essential for patients to understand their diagnosis and symptoms and actively participate in treatment. Movement retraining shows patients that normal movement is possible in the context of routine daily activities. The key to retraining is to minimise self-directed attention through distraction (music, changes in rhythm, tapping); this reduces cognitive control of movement, which becomes more automatic. To retrain movement, movements are broken down into elementary asymptomatic motor components, which are subsequently rearranged to reconstruct a normal movement pattern.23 In this process, neurorehabilitation uses the general principles of movement retraining32: repetition of task-oriented exercises, gradually increasing task difficulty, and feedback (mirror training, videos, EMG, etc.). Lastly, a self-management plan is essential; this is usually based on the use of a workbook. The contents of the workbook include strategies aimed at normalising movement, a list of precipitating and perpetuating factors, markers of progress, and future goals.33

The studies included in our review used highly variable programmes, both in terms of number of sessions and in the duration of each session and the overall intervention. Interventions took place on an outpatient basis in 2 studies and with inpatient programmes in the remaining 2. Broadly speaking, inpatient treatment programmes are more intensive.28 However, in other studies not included in our review (both prospective and retrospective), interventions were predominantly inpatient programmes.34–40 However, studies of outpatient interventions have been published that include large samples and report favourable results41; some studies employ a mixed design, where patients complete an inpatient rehabilitation programme followed by a supervised, home-based self-management plan.42

Most studies used pre-established similar inclusion criteria for selection of participants, such as those proposed by Gupta and Lang.16

All studies included long follow-up times, with patients being monitored in the medium and long term. This seems reasonable due to the chronic nature of the disease and the need to evaluate whether the benefits of the intervention are persistent.

The outcome measures used to evaluate changes varied according to the factor analysed: motor symptoms, activity and quality of life, perceived health status, and cognitive and emotional status. In all studies, the physical therapy intervention resulted in improvements in scale scores. Some researchers have focused on the development of assessment tools specifically designed for FMD, such as the Psychogenic Movement Disorders Rating Scale43 and the more recent Simplified Functional Movement Disorders Rating Scale.44 Several authors31,45 have reviewed these scales and issued recommendations on the most appropriate outcome measures. Although standardisation of specialised physical therapy for FMD is currently underway, the approaches proposed by different authors continue to present discrepancies. The multicentre study by Nielsen et al.46 may shed some light onto some of these questions, given the large population included and the fact that it mixes both inpatient and outpatient interventions.

Telerehabilitation programmes have recently been introduced in clinical practice, such as those developed by Gelauff et al.,47 in which patients had access to a non-guided education and self-help website in addition to standard care, and by Demartini et al.,48 who combined in-person sessions and telemedicine sessions. It remains to be determined whether telerehabilitation alone is sufficient or whether it should be applied in the context of a multidisciplinary in-person treatment programme. There can be no doubt that new technologies enable more fluent patient-therapist communication, improving patients’ access to relevant information on their condition.

This systematic review presents a number of limitations. Firstly, it includes a limited number of studies, which resulted in a small sample of patients. Secondly, the intervention varied between studies. Furthermore, the number and duration of the sessions varied between studies, preventing us from objectively comparing their results. Lastly, as we only included studies published in English or Spanish, we may have missed relevant studies in other languages.

ConclusionsPhysical therapy for patients with FMD improves motor symptoms, activity, perceived health, and quality of life. However, there is a need for further well-designed studies to evaluate the effects of this type of intervention in different contexts and establish the most appropriate dose and treatment approach for each patient, as well as reliable outcome measures.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.