We report the development and validation of a unique, easily administered, but cognitively demanding 3-min test that does not require aids and can detect mild cognitive deficits (MCD).

MethodsThe innovative Amnesia Light and Brief Assessment (ALBA) consists of 4 tasks: encoding the 6-word sentence “Indian summer brings first morning frost,” sequential demonstration of 6 gestures and their immediate recall, and final recall of the original sentence. The memory ALBA score is the sum of all correctly recalled sentence words and gestures. The ALBA was performed in 590 persons older than 50 years, including 60 individuals who completed a neuropsychological battery, equally divided into patients with MCD (Montreal Cognitive Assessment [MoCA] score of 21±3 points) and matched cognitively normal (CN) individuals (MoCA of 27±2).

ResultsCompared to CN individuals, the patients with MCD recalled fewer correct sentence words (median, 5 vs 2) and gestures (4 vs 3), and had lower memory ALBA scores (10 vs 6) (all comparisons, P<.00001). The cut-off point for the memory ALBA score was ≤8, with 90% sensitivity, 77% specificity, and an AUC of 0.90. Memory ALBA score correlated significantly with all neuropsychological tests except the Digit Span forward. The ALBA was minimally associated with education and age in the normative sample.

ConclusionsThe novel and efficient ALBA test was confirmed to have high discriminant and convergent validity, even in patients with mild cognitive deficits. The ALBA is an ultra-brief and universal cognitive test suitable for assessing cognitive impairment, dementia, and other conditions. It can easily be adapted to other cultures and administered under various conditions and settings in clinical practice and research.

Desarrollo y validación de una prueba de 3min única, fácil de administrar, pero cognitivamente exigente que no requiere ayudas y puede detectar déficits cognitivos leves.

MétodosLa innovadora evaluación breve y ligera de amnesia (ALBA) consta de 4 tareas: codificación de una oración de 6 palabras «Indian Summer Brings First Morning Frost», demostración secuencial de 6 gestos y su recuerdo inmediato, y recuerdo final de la oración original. La puntuación ALBA es una suma de palabras de una frase y gestos recordados correctamente. El ALBA se realizó en 590 personas mayores, incluidas 60 personas con una batería neuropsicológica dividida equitativamente en pacientes con déficit cognitivo leve (MCD) (evaluación cognitiva de Montreal: 21±3 puntos) e individuos cognitivamente normales (CN) emparejados (MoCA 27±2).

ResultadosEn comparación con CN, los pacientes con MCD recordaron menos palabras de oraciones correctas (mediana de 5 frente a 2), gestos (4 frente a 3) y puntuaciones ALBA más bajas (10 frente a 6) (todos p<0,00001). El punto de corte de la puntuación ALBA fue ≤8 con una sensibilidad del 90%, una especificidad del 77% y un AUC de 0,90. Se correlacionó significativamente con todas las pruebas neuropsicológicas excepto con Digit Span Forward. El ALBA se asoció mínimamente con la educación y la edad en la muestra normativa.

ConclusionesSe confirmó que la nueva y eficiente prueba ALBA tiene una alta validez discriminante y convergente incluso en aquellos con déficits cognitivos leves. El ALBA es una prueba cognitiva ultrabreve y universal adecuada para evaluar el deterioro cognitivo, la demencia y otras condiciones. Puede adaptarse fácilmente a otras culturas y administrarse en diversas condiciones y entornos en la práctica clínica y la investigación.

A dream and a challenge for busy clinicians would be a single brief test to detect unrecognized and early cognitive impairment. Assessing a patient's memory contributes to diagnosis and allows enrollment in clinical trials and facilities for comprehensive management, treatment, care, and interventions.1,2 Cognitive dysfunction can be a common presentation of many primary brain disorders in neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry, such as Alzheimer disease (AD), Lewy body disease, vascular dementia, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, stroke, head trauma, hydrocephalus, depression, and schizophrenia. It may also be a secondary manifestation of medication side effects or inflammatory, organ, systemic, or somatic conditions, such as cardiovascular or kidney disease, diabetes, or COVID-19.3–7 The perioperative community is also increasingly interested in patients’ cognitive status, which should be considered during pre- and postoperative care in elderly patients undergoing surgery and anesthesia (perioperative neurocognitive disorders).8

A variety of cognitive tests are used in everyday practice to measure cognitive deficits. These differ in terms of administration, scoring, sensitivity, specificity, and administration time.1,2,9–24 We adapted and validated 2 tests, including their norms.25,26 However, many clinics are so overwhelmed that they cannot even afford to use test batteries, since these often take 5–20min or longer to administer and score.1,18 Speed and ease of test administration were the most important aspects in choosing a particular cognitive test.2 Additionally, all tests require testing skills, test forms, or special aids. Some are copyrighted and require payment.1,17,27,28 Very brief tests, taking up to 5min, include the Clock-Drawing Test (CDT) and the Mini-Cog, which explore long-term memory via the determination of time using clock faces, or short-term memory via testing of 3-word groups.1,29,30 In our experience, the CDT presents poor diagnostic accuracy in patients with early AD.31 The use of the Mini-Cog is still questionable in primary care.30

Very brief cognitive instruments are pencil-and-paper tests whose scores may be influenced by age and level of education.1,18–21 These tests usually distinguish frank dementia from normal cognition, but provide limited discrimination between normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and mild dementia. MCI is an alteration to cognitive function compared to the population matched for age and education level, but without loss of functional abilities and skills in everyday social and occupational life.18 Simple tools to support clinical history-taking are most needed in the assessment of individuals with mild cognitive deficits (MCD). Early detection provides the opportunity for further diagnostic studies and a comprehensive, personalized management and treatment plan. Caregivers are able to better understand symptoms and changes and to obtain appropriate information and community support.2

Some published tests have not been validated for MCI or present poor psychometric properties as the included tasks are too easy (ceiling effect); an example is the CDT, which also has different administration and scoring systems.1 Overall, there is a need for better very brief instruments to screen for MCD and mild dementia in primary care and during first contact.

We attempted to overcome some of the disadvantages of current instruments. We feel that a universal test, suitable for use across different disciplines, should be free, with minimal influence due to age and education level, and very brief (taking less than 5min), yet able to detect MCD. Additionally, it should not require special aids or skills, such as pencils, paper, stimulus materials, writing, or reading. For several years we have been working to develop an ultra-brief cognitive test using a single sentence and several gestures.32–34 This unique examination contains 2 memory tasks (Amnesia), and is easy (Light) and brief (Brief) to administer and score (Assessment). Therefore, the abbreviated name given to the test is the ALBA test. The first experiences and results of this test were reported in the journal Czech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery.32,33,35 We demonstrated that remote administration of the ALBA between 2 monitors gives the same results as those obtained in person.36 This report is the first international presentation of the ALBA test.

The aim of this study was to introduce and validate the ALBA test, which is a newly developed, original, brief cognitive assessment tool. Administration and scoring were completed without special aids, within 2–3min. The discriminant and convergent validity of the ALBA test were demonstrated. We hypothesized a close relationship between ALBA and memory tests, but not with non-memory tests. Finally, we assumed negligible sociodemographic influence on test scores due to its underlying principles. In addition, we also established ALBA norms in a large group of cognitively normal (CN) elderly individuals. The ALBA test has excellent psychometric properties for discriminating between cognitively normal individuals and individuals with mildly impaired cognition and correlates with many cognitive functions; the influence of education and age is negligible.

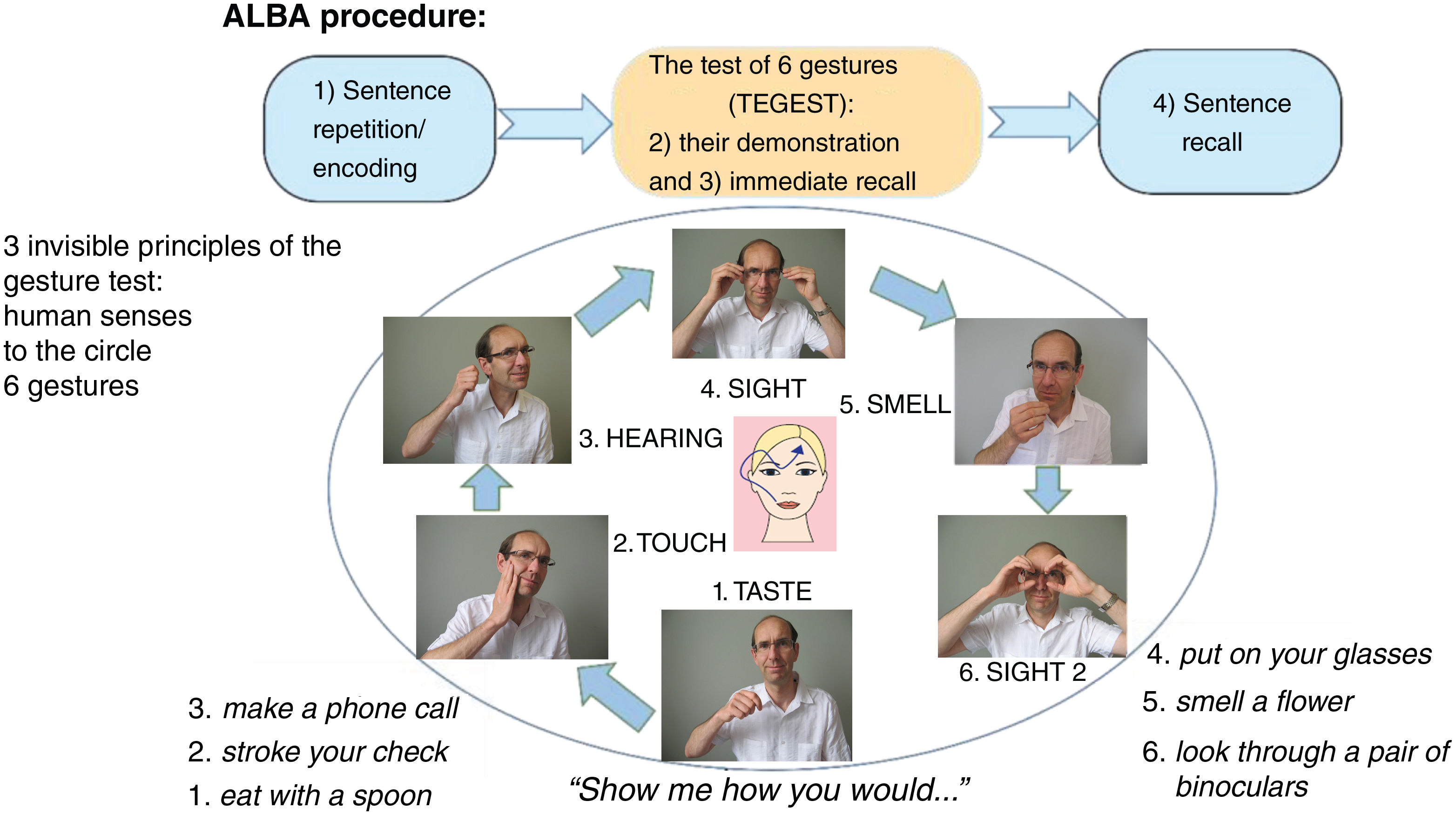

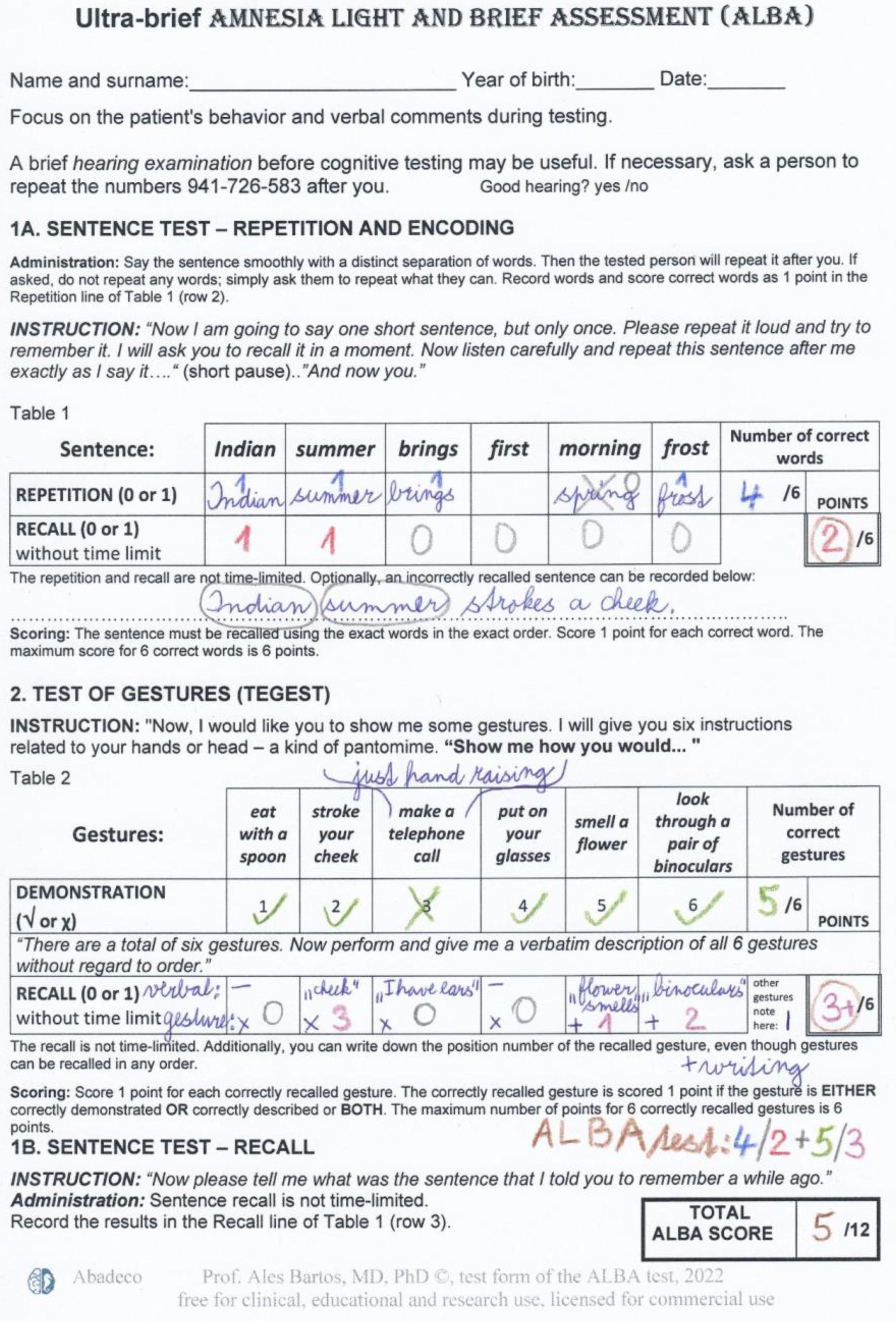

Methods and participantsDescription and administration of the Amnesia Light and Brief Assessment (ALBA) testThe innovative ALBA test consists of 2 tests and 4 tasks. It involves the learning and recall of a single but somewhat complicated sentence, interrupted with a gesture test (TEGEST). The gesture test serves as a stand-alone test and simultaneously as a distraction for the sentence recall test. An overview of ALBA procedures is summarized in Fig. 1. Detailed instructions and scoring are explained and shown in a completed example of the ALBA test, with results, in Fig. 2.

The sentence in the ALBA test is emotionally and gender-neutral: “Indian summer brings first morning frost.” Since the sentence is easy to remember, it is read to the examinee only once to save time. This first task reflects (1) language (which is impaired in some forms of aphasia) and (2) encoding and short-term memory (impaired memory and attention deficits).

The participants are asked to perform a series of 6 gestures, following the examiner's instructions, during the middle part (TEGEST). The gestures are based on 3 principles of a paradigm shown in Fig. 1. First, each gesture is related to one of the 5 human senses. Second, a second gesture associated with sight is added to increase the number of items and make the test more difficult. Third, the order of the gestures approximates a clock-wise progression: (1) the mouth (taste), (2) the cheek (touch), (3) the ears (hearing), (4) the eyes (sight), and (5) the nose (smell), as shown in Fig. 1. This mnemonic arrangement helps the administrator remember the sequence of gestures and makes administration easier. However, the person being tested is unlikely to discover this underlying cue. Gesturing can be impaired as a result of sensory aphasia or apraxia.

The participants are not told beforehand that they should try to remember the gestures. After performing the set of gestures, they are asked to, immediately and without distraction, recall, demonstrate, and verbally describe the gestures. The ALBA test is concluded with sentence recall. Short-term and episodic memory is measured in 2 different ways: (1) in the third part of the ALBA, testing incidental memory of the gestures), and (2) in the fourth part, which tests intentional verbal memory of the sentence.

Evaluation of the ALBA testScores for individual parts range from 0 (worst performance) to 6 points (best performance) for each of 4 tasks: (1) the number of correctly repeated words from the sentence (Word 1 score: 0–6 points), (2) the number of correctly recalled words from the sentence after distraction using the TEGEST (W2 score: 0–6), (3) the number of correctly performed gestures in the TEGEST (Gesture 1 score: 0–6), and (4) the number of correctly recalled gestures in the TEGEST (G2 score: 0–6). The sum, called the memory ALBA score, is derived from correctly recalled words in the sentence and correctly recalled gestures (W2+G2: 0–12 [6+6]). An example of ALBA test scores shown in Fig. 2, is as follows: 5/1+5/3 (W1/2+G1/2), which gives a total memory ALBA score of 4 (1+3 points).

Neuropsychological battery as a reference standardA one-hour battery of neuropsychological tests and questionnaires was administered as a reference standard and scored by a trained psychologist (SD) to cover all cognitive functions, mood, and activities of daily living; define groups; and correlate these measures with the ALBA test scores.37 The ALBA test was performed by an experienced memory clinic nurse, research assistants, or students who had been repeatedly trained before ALBA administration. The neuropsychological assessment was performed on the same day as the ALBA or in 3 months’ time (range, 1–6 months). General cognitive functions were examined with the Czech-language version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA-CZ) as part of our previous large study.25 These cognitive functions were evaluated using a neuropsychological battery assessing immediate and delayed recall, verbal and visual memory, semantic memory, executive functions, language, visuospatial functions, psychomotor speed, and attention. Individual tests are described in association with their correlations in results. The CDT was assessed using 3 scoring systems.16,29,31 Depression was evaluated using the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) to screen for the presence and severity of reported depressive symptoms, which could impact cognitive performance.37 Activities of daily living were assessed using our adapted Czech-language version of the Functional Assessment Questionnaire (FAQ-CZ) by patient proxy or by participants (in CN elderly individuals).38

Participants and their inclusion criteriaThis was a prospective study conducted at 2 recruitment centers at the University Hospital Kralovske Vinohrady and the National Institute of Mental Health in the Czech Republic, between 2016 and 2021. Data collection was planned before the ALBA test and reference standards were performed. The ALBA test was used to examine 590 elderly persons. A neuropsychological battery was used in 60 individuals equally divided into patients with MCD, and sociodemographically-matched CN individuals. All participants had GDS scores≤6 points.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for CN elderly people were assessed during a brief interview based on a questionnaire. We recruited spouses of patients, volunteers from our previous and ongoing normative studies, and members of senior clubs, churches, etc. Inclusion criteria were age over 50 years, speaking Czech as their native language, and independent living in the community. Exclusion criteria were psychiatric or neurological disorders (e.g., stroke, trauma, tumor, alcohol abuse, and psychoactive medications). The same procedure was used in our previous normative and validation studies.25,26

Patients with MCD were recruited consecutively if they met the following inclusion criteria: under long-term follow-up at the memory center of the Department of Neurology, University Hospital Kralovske Vinohrady, Prague, Czech Republic; presenting a neurocognitive disorder based on the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5 (DSM 5),39 as determined by an experienced cognitive neurologist (AB); and MCD, based on MoCA-CZ scores≥15 points (equivalent to an estimated≥21 points on the Mini-Mental State Examination).15,26

The reference standard for patients with MCD included clinical diagnosis and the current neuropsychological battery. The patients group consisted of 14 patients with mild neurocognitive disorders (3 with mild neurocognitive disorder due to AD), 6 with major neurocognitive disorder due to AD, 7 with major frontotemporal neurocognitive disorders, and 3 with unspecified neurocognitive disorder according to the criteria of the American Psychiatric Association.39 All patients were found to have MCD based on the MoCA, with functional impairment being absent (mild neurocognitive disorder) or mild (major neurocognitive disorder) according to the FAQ-CZ filled-in by the patient's caregiver. Thus, patients with major neurocognitive disorders had initial and mild dementia.

CN elderly individuals were included in the control group if they met the previously described inclusion and exclusion criteria, and had normal neuropsychological and GDS scores according to Czech norms published by our National Institute of Mental Health.40

All participants signed informed consent forms. The study was approved by the National Institute of Mental Health, Klecany on 17st March 2016 (51/16) and the Ethics Committees of the University Hospital Kralovske Vinohrady, Prague on 2nd February 2019 (EK-VP/03/02019). The study conforms with World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysisSociodemographic variables and test scores were compared between the MCD (n=30) and CN groups (n=30) using the Mann–Whitney U test and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The area under the ROC curve, abbreviated as AUC, is a single value that measures the overall performance of a binary classifier. The AUC can be interpreted as the probability that a randomly selected diseased subject is rated or ranked as more likely to be diseased than a randomly selected healthy subject. Such an index is especially useful in a comparative study of 2 diagnostic tests.41 AUC values may be classified as follows: 0.9–1.0=excellent, 0.8–0.9=very good, 0.7–0.8=good, 0.6–0.7=sufficient, and 0.5–0.6=poor.42 The Chi-square test was used to compare categorical data between these 2 groups. The Youden index was used to identify the best cut-off score with the highest sum of sensitivity and specificity. Sensitivity or specificity values of 80% or greater were considered to be high. These thresholds were used to select tests in a recent review.18 The Spearman correlation coefficient was used to verify the convergent validity of the ALBA test and its relationship with age and education level in the control sample of CN elderly people (n=560). Linear regression analyses were performed to assess the relative contributions of age and education to the participant's total memory ALBA score in the normative sample of CN elderly people (n=560) and to predict MoCA scores based on the memory ALBA score in the control and patient groups with a neuropsychological assessment (n=60). Analysis was performed with the Statistica and MedCalc software. P-values<.05 were considered statistically significant. The Bonferroni correction was used where appropriate.

ResultsThe mean (standard deviation [SD]) administration and scoring time of all 4 tasks of the ALBA test was 2.3 (0.6)min (p25–p75, 2–3min; median, 2min; range, 1–5min) in 260 random participants.

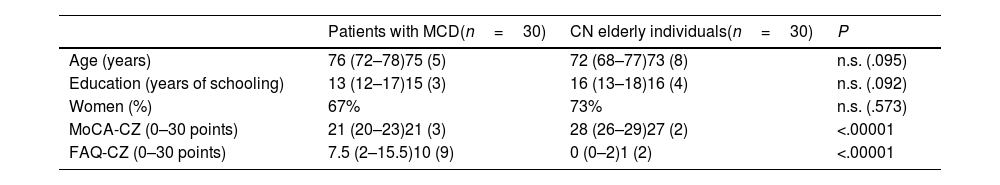

Discriminant validity of the ALBA testThe 2 groups undergoing neuropsychological assessments were matched according to age, education level, and sex, but differed in cognitive function and activities of daily living (Table 1). Note that the cognitive function of patients were only very mildly impaired. The average MoCA-CZ score of 21 points in the patient group would correspond to approximately 26 points on the MMSE.15,26 Similarly, activities of daily living in the patient group were also mildly impaired according to FAQ-CZ scores (10±9 points).

Participant characteristics, by group.

| Patients with MCD(n=30) | CN elderly individuals(n=30) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 76 (72–78)75 (5) | 72 (68–77)73 (8) | n.s. (.095) |

| Education (years of schooling) | 13 (12–17)15 (3) | 16 (13–18)16 (4) | n.s. (.092) |

| Women (%) | 67% | 73% | n.s. (.573) |

| MoCA-CZ (0–30 points) | 21 (20–23)21 (3) | 28 (26–29)27 (2) | <.00001 |

| FAQ-CZ (0–30 points) | 7.5 (2–15.5)10 (9) | 0 (0–2)1 (2) | <.00001 |

CN: cognitively normal; FAQ-CZ: Czech-language version of the Functional Activities Questionnaire; MCD: mild cognitive deficits; MoCA-CZ: Czech-language version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment; n.s.: not significant.

Data are presented as the median (percentiles 25 and 75) or mean (standard deviation). Female sex is expressed as percentage.

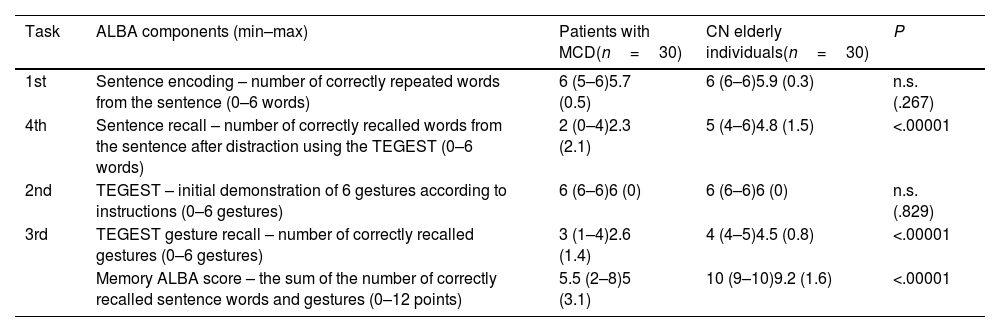

Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1 present the comparisons of ALBA test scores. Patients with MCD correctly repeated and encoded sentence words and correctly demonstrated gestures in response to the administrator's instructions. They performed both tasks at normal levels, similarly to the CN group, and with no statistically significant difference. However, they recalled significantly fewer words from the sentence and fewer gestures, and had lower memory ALBA scores (sum of correctly recalled words and gestures) than the CN group (P<.00001 for all differences).

Results in individual parts of the ALBA test and comparison between patients with mild cognitive deficits and sociodemographically matched cognitively normal elderly individuals.

| Task | ALBA components (min–max) | Patients with MCD(n=30) | CN elderly individuals(n=30) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Sentence encoding – number of correctly repeated words from the sentence (0–6 words) | 6 (5–6)5.7 (0.5) | 6 (6–6)5.9 (0.3) | n.s. (.267) |

| 4th | Sentence recall – number of correctly recalled words from the sentence after distraction using the TEGEST (0–6 words) | 2 (0–4)2.3 (2.1) | 5 (4–6)4.8 (1.5) | <.00001 |

| 2nd | TEGEST – initial demonstration of 6 gestures according to instructions (0–6 gestures) | 6 (6–6)6 (0) | 6 (6–6)6 (0) | n.s. (.829) |

| 3rd | TEGEST gesture recall – number of correctly recalled gestures (0–6 gestures) | 3 (1–4)2.6 (1.4) | 4 (4–5)4.5 (0.8) | <.00001 |

| Memory ALBA score – the sum of the number of correctly recalled sentence words and gestures (0–12 points) | 5.5 (2–8)5 (3.1) | 10 (9–10)9.2 (1.6) | <.00001 |

ALBA: Amnesia Light and Brief Assessment; CN: cognitively normal; MCD: mild cognitive deficits; n.s.: not significant; TEGEST: test of gestures.

Data are presented as the median (percentiles 25 and 75) and mean (standard deviation).

Sensitivity and the AUC of the memory ALBA score are high enough that even MCD can be detected. The optimal cut-off point for the memory ALBA score was ≤8 points, with 90% sensitivity, 77% specificity, and an AUC of 0.90 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Supplementary Table 1 shows the cut-off scores, sensitivities and specificities, and AUCs for the 2 subtests and for the total ALBA test score.

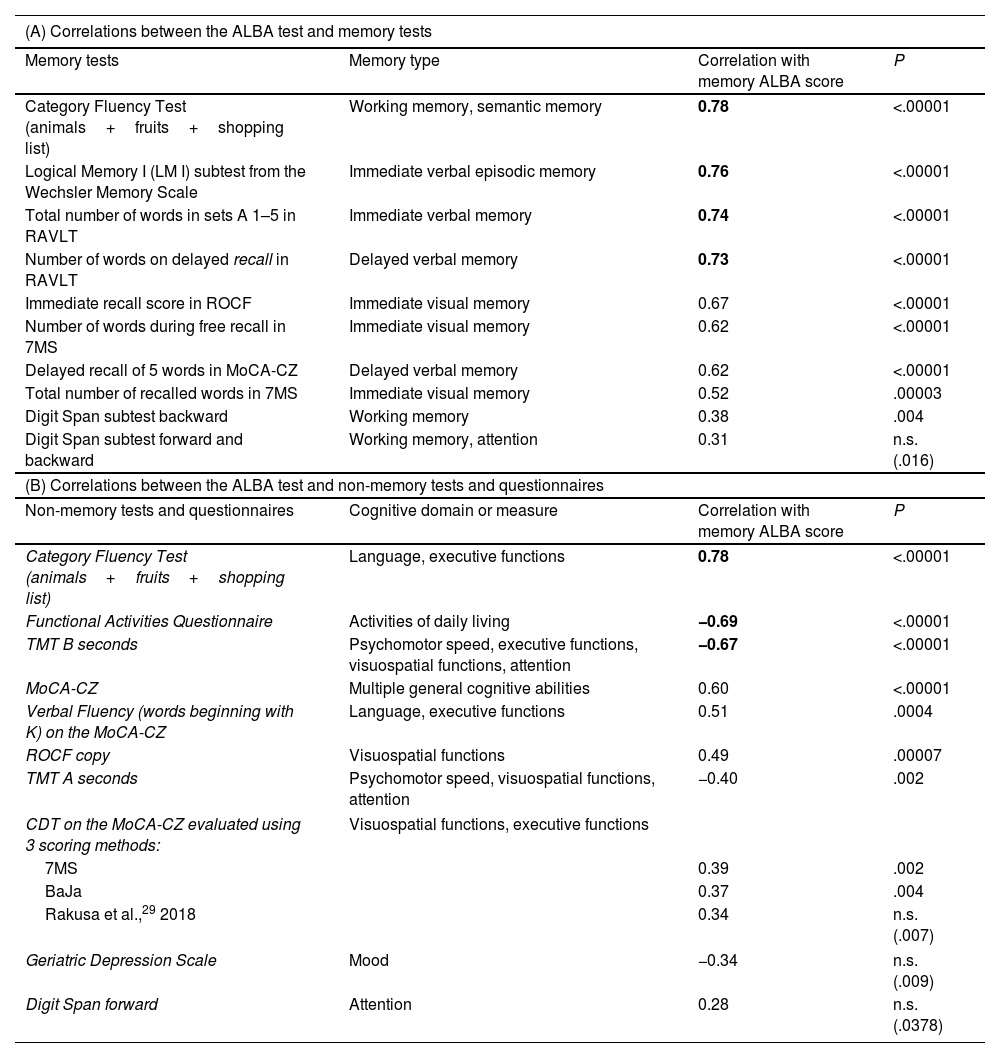

Convergent validity between the ALBA test and neuropsychological tests and questionnairesA further objective was to establish whether the ALBA test correlates with traditional neuropsychological tests of memory and other non-memory cognitive domains. Neuropsychological assessment results are available in Supplementary Table 2. Moderate and strong statistically significant correlations were found between ALBA test scores and scores on all memory and non-memory tests, as shown in Table 3A and B. Although ALBA test scores are significantly correlated with scores in the Digit Span test forward and backward (Table 3A) and with scores in the Digit Span test forward (Table 3B), they lost significance after application of the Bonferroni correction for multiple correlations. Estimated MoCA scores can be simply calculated as 17 points plus the memory ALBA score, using the following regression formula: MOCA score=17.3171+0.9590×memory ALBA score.

Correlations between memory ALBA score and scores in neuropsychological memory tests (A) and neuropsychological non-memory tests, the Geriatric Depression Scale, and the Functional Activities Questionnaire (B), ordered by correlation values in the total sample (n=60).

| (A) Correlations between the ALBA test and memory tests | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Memory tests | Memory type | Correlation with memory ALBA score | P |

| Category Fluency Test (animals+fruits+shopping list) | Working memory, semantic memory | 0.78 | <.00001 |

| Logical Memory I (LM I) subtest from the Wechsler Memory Scale | Immediate verbal episodic memory | 0.76 | <.00001 |

| Total number of words in sets A 1–5 in RAVLT | Immediate verbal memory | 0.74 | <.00001 |

| Number of words on delayed recall in RAVLT | Delayed verbal memory | 0.73 | <.00001 |

| Immediate recall score in ROCF | Immediate visual memory | 0.67 | <.00001 |

| Number of words during free recall in 7MS | Immediate visual memory | 0.62 | <.00001 |

| Delayed recall of 5 words in MoCA-CZ | Delayed verbal memory | 0.62 | <.00001 |

| Total number of recalled words in 7MS | Immediate visual memory | 0.52 | .00003 |

| Digit Span subtest backward | Working memory | 0.38 | .004 |

| Digit Span subtest forward and backward | Working memory, attention | 0.31 | n.s. (.016) |

| (B) Correlations between the ALBA test and non-memory tests and questionnaires | |||

| Non-memory tests and questionnaires | Cognitive domain or measure | Correlation with memory ALBA score | P |

| Category Fluency Test (animals+fruits+shopping list) | Language, executive functions | 0.78 | <.00001 |

| Functional Activities Questionnaire | Activities of daily living | −0.69 | <.00001 |

| TMT B seconds | Psychomotor speed, executive functions, visuospatial functions, attention | −0.67 | <.00001 |

| MoCA-CZ | Multiple general cognitive abilities | 0.60 | <.00001 |

| Verbal Fluency (words beginning with K) on the MoCA-CZ | Language, executive functions | 0.51 | .0004 |

| ROCF copy | Visuospatial functions | 0.49 | .00007 |

| TMT A seconds | Psychomotor speed, visuospatial functions, attention | −0.40 | .002 |

| CDT on the MoCA-CZ evaluated using 3 scoring methods: | Visuospatial functions, executive functions | ||

| 7MS | 0.39 | .002 | |

| BaJa | 0.37 | .004 | |

| Rakusa et al.,29 2018 | 0.34 | n.s. (.007) | |

| Geriatric Depression Scale | Mood | −0.34 | n.s. (.009) |

| Digit Span forward | Attention | 0.28 | n.s. (.0378) |

The strongest correlations are highlighted in bold.

7MS: 7Minute Screen Test; ALBA: Amnesia Light and Brief Assessment; BaJa: scoring by Bartos and Janousek; CDT: the Clock Drawing Test; MoCA-CZ: Czech-language version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment; n.s.: not significant after Bonferroni correction; RAVLT: Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; ROCF: Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure test; TMT A and B: Trail Making Test parts A and B.

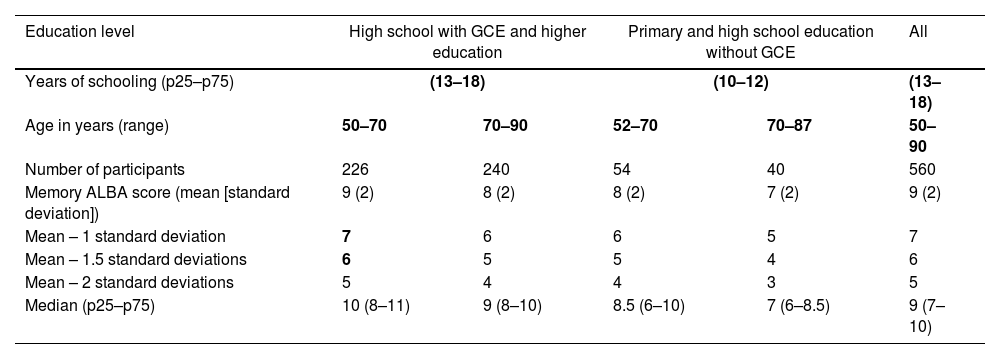

Normative scores for the first 2 tasks on the ALBA test, based on results of 560 individuals, are as follows: (1) the number of correctly repeated words in the sentence: mean (SD), 5.8 (1.7); median (p25–p75), 6.0 (6.0–6.0); and (2) the number of correctly demonstrated gestures: mean (SD), 6.0 (0.2); median (p25–p75), 6.0 (6.0–6.0). Detailed normative data for the third and the fourth tasks (sentence and gesture recall) and memory ALBA scores are presented in Table 4. These data include reference values and clinically relevant lower limits using standard deviations subtracted from means and percentiles for the memory ALBA score and its subscores. Supplementary Fig. 3A–C shows the distribution of the number of correctly recalled words from the sentence (A), gestures (B), and their sum (C) on the ALBA test.

Normative data for the memory ALBA score, stratified by education level and age.

| Education level | High school with GCE and higher education | Primary and high school education without GCE | All | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years of schooling (p25–p75) | (13–18) | (10–12) | (13–18) | ||

| Age in years (range) | 50–70 | 70–90 | 52–70 | 70–87 | 50–90 |

| Number of participants | 226 | 240 | 54 | 40 | 560 |

| Memory ALBA score (mean [standard deviation]) | 9 (2) | 8 (2) | 8 (2) | 7 (2) | 9 (2) |

| Mean – 1 standard deviation | 7 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 7 |

| Mean – 1.5 standard deviations | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 6 |

| Mean – 2 standard deviations | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 |

| Median (p25–p75) | 10 (8–11) | 9 (8–10) | 8.5 (6–10) | 7 (6–8.5) | 9 (7–10) |

| Memory ALBA score (points) | Percentiles | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 2 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 4 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 4 |

| 5 | 5 | 12 | 7 | 10 | 9 |

| 6 | 11 | 15 | 26 | 30 | 15 |

| 7 | 18 | 25 | 43 | 53 | 25 |

| 8 | 27 | 41 | 50 | 75 | 38 |

| 9 | 46 | 64 | 67 | 88 | 58 |

| 10 | 73 | 84 | 85 | 98 | 81 |

| 11 | 94 | 98 | 96 | 100 | 96 |

| 12 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

ALBA: Amnesia Light and Brief Assessment; GCE: general certificate of education (school leaving certificate/high school diploma); p25–p75: percentiles 25 and 75.

Normative data are expressed as mean (standard deviation) or median (percentiles 25 and 75). Cut-off points are based on subtraction of standard deviations from the means, and scores were converted to percentiles in the 4 subgroups stratified by age and education and in the entire normative group. We calculated the lower limits of normal aging using SD and percentiles for the following 3 degrees of cognitive function: mean – 1 SD (16th percentile) for early mild cognitive impairment, mean – 1.5 SD (7th percentile) for late mild cognitive impairment, and mean – 2 SD (2nd percentile) for dementia.

Borderline scores (the memory ALBA score of 6 points for less educated people and 7 points for more educated people) and their corresponding percentiles are shown in bold numbers.

The influence of sociodemographic characteristics was studied in 560 CN elderly individuals with the following characteristics: mean age (SD) 70 (8) years, 15 (3) years of schooling, 71% women, and a mean MoCA-CZ score of 26 (3) points (n=385). None of the 5 ALBA variables differed between women and men (sentence encoding, P=.2; sentence recall, P=.8; TEGEST – initial gesture demonstration, P=.9; TEGEST gesture recall, P=.8; memory ALBA score, P=1.0). Age and education were inversely correlated, at similar absolute values, with sentence repetition (− for age/+ for education 0.15), sentence recall (−/+0.25), gesture recall (−/+0.15), and memory ALBA score (−/+0.2) (all P<.001), but not with gesture demonstration (not significant). Education- and age-adjusted norms for memory ALBA scores are presented in Table 4. They show very small changes in cut-off points. Numbers of correctly recalled sentence words and gestures are shown in Supplementary Table 4.

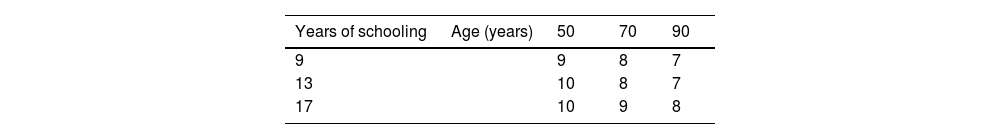

Based on the results regarding sociodemographic influence on ALBA test scores, linear regressions accounted for education and age, but not sex. The regression equations are as follows: memory ALBA score=6.4+0.15*education (R2=0.06), memory ALBA score=13.0−0.06*age (coefficient of determination R2=0.06), and memory ALBA score=10.6+0.1*education−0.05*age (R2=0.10). Thus, a one-point change in memory ALBA score is expected for every 10 years of education and 20 years of age (with the rest of the predictors remaining constant). Table 5 shows regression-based normative data for memory ALBA scores stratified by education and age. Education level was defined according to the 3 most frequent levels in the country (primary education after 9 years, secondary education after 13 years, and tertiary education after 17 years). Age examples included the whole range of the normative sample (50–90 years) divided per 20 years, with memory ALBA score changes based on regression.

Regression-based normative data for the memory ALBA score stratified by education and age.

| Years of schooling | Age (years) | 50 | 70 | 90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 9 | 8 | 7 | |

| 13 | 10 | 8 | 7 | |

| 17 | 10 | 9 | 8 |

Memory ALBA scores were calculated using the following regression formula: memory ALBA score=10.6101+0.1355*education−0.055593*age.

ALBA: Amnesia Light and Brief Assessment.

Since education had a greater influence on memory ALBA scores than age, the entire sample was divided into 2 subgroups according to median years of schooling, which was 15 years.

The lower- and higher-educated subgroups did not differ much from the scores above the 16th percentile for individual items: (1) sentence repetition/encoding: 5 vs 6, (2) sentence recall: 2 vs 3, (3) gesture demonstration: 6 vs 6, (4) gesture recall: 3 vs 4, and (5) memory ALBA scores: 6 vs 8. Similarly, dichotomizing the sample by education to those with and without a General Certificate of Education (a school-leaving certificate/high school diploma) resulted in negligible differences in the same variables, in the same order: 5 vs 5, 2 vs 3, 6 vs 6, 3 vs 3, and 6 vs 7. These results correspond to similar cut-off points to those established for the entire sample: 5, 3, 6, 3, and 7.

DiscussionThe ALBA test is an innovative, valid instrument presenting many advantages for busy clinicians and other professionals. It comprises 4 different tasks in one test (hence the word “Assessment” in the test name). Sentences are used by everybody during conversations. Thus, sentence recall is more ecological than tests that involve learning a word list. Demonstrations of gestures following instructions and their subsequent recall imitate important skills used in daily living, such as determining whether somebody took their medication. The ALBA test is sufficiently difficult for those tested that it can reveal MCD, as demonstrated by our study. The 2 recall tasks, as components of the memory ALBA score, assess different types of memory (i.e., “Amnesia” in the test name). They were also related to other cognitive functions, as evidenced by the correlations with various neuropsychological scores. Unique testing is simple to use for administrators (thus “Light”). No special aids or forms are needed, and test administrators can easily perform the ALBA test from memory. The sentence is short and easy for the administrator to remember. The gestures used in the test are associated with a mnemonic with a logical connection. As a result, the ALBA test can be carried out almost anywhere and at any time, even with patients who are visually impaired or unable to leave bed. The ultra-brief administration and scoring only take a total of 2–3min (hence “Brief”), making it 5 times quicker than the MoCA test, for instance.25 Altogether, this newly developed paradigm is unique and ideal for clinical practice, research, or recruitment use in clinical trials.

The ALBA has favorable psychometric properties, even in mildly affected patients with estimated average MMSE scores of around 26 points. The gold standard for defining the 2 groups included both a clinical diagnosis, established according to the DSM 5 criteria, and a neuropsychological assessment. The high discriminant validity of the ALBA was determined in the first report,33 in which a group of normally aging elderly individuals (n=62; median age, 75 years; median education, 13 years; 79% women) was compared to patients with MCI (n=62; median age, 77 years; median education, 13 years; 66% women). The mean memory ALBA score in the group of normally aging persons was 9 (2) points, compared to 4 (3) points in the patient group. Sensitivity was 90% (high) and specificity was 74% at a cut-off score of ≤7 points. Discrimination was excellent, with an AUC of 0.92 (Supplementary Table 3). High sensitivity (90%) and moderate-high specificity (77%), even among patients with MCD, are the major advantages of the ALBA test.41,42 Sensitivity and specificity values would be higher if patients with greater impairment (i.e., average MMSE scores<26 or MoCA<21 points) had been included. Three independent sources tend to show similar cut-off points as the memory ALBA score between 6 and 8 points: (1) the normative sample of 560 individuals, (2) comparisons between the CN and patient groups in the current study, and (3) results in the very first study.33 Taken together, the presented norms and cut-off points for the ALBA test are consistent and reliable.

The psychometric properties of the ALBA test were compared to those of other brief assessment tools with similar characteristics, i.e., free of charge, screening for MCD, and with a duration of less than 3min (Supplementary Table 3).1,21 Generally, the sensitivities, specificities, Youden indices, and AUCs of these tests are lower than those of the ALBA test. The majority present poor sensitivity and Youden index values. Some have sensitivity as low as 17–50%, and the Youden index ranges between 0.17 and 0.55. Such tests are not useful for clinical practice. Only the ALBA test has excellent discrimination (AUC of 0.90–0.92).42 Therefore, the ALBA is the first and most efficient test to detect MCD quickly in many clinical situations and settings. Moreover, the ALBA test provides further benefits over other brief tests, i.e., a very short duration with excellent psychometric properties for MCD. Unlike other tests, the ALBA can be administered without paper and pencil, and the test can be administered from memory.

The 4 individual tasks of the ALBA test have different potentials to discriminate between normal aging and MCD. We expected that the scores for the first 2 tasks would be the highest, even in mildly affected patients. This was confirmed, with normal or almost normal performances in our 30 patients (Table 2) and 560 CN elderly individuals in the normative sample, as described in the results. This is logical, since both tasks are easy to perform. It also means that persons with normal or mildly impaired cognitive functions are sure to register and encode one short sentence and demonstrate 6 gestures. This is an important condition for their recall. The difference between the 2 types of recall in the ALBA is that examinees are instructed to remember the sentence but not the gestures. Thus, gesture recall is more difficult because examinees are not asked to remember them beforehand. Sentence recall is difficult because of the distraction from the gesture tasks. Elderly people should recall at least half the maximum number of gestures and sentence words, i.e., 3 correct gestures and 3 correct sentence words. We can summarize mnemonic rules of 100% and 50% of the maximum possible performance to remember approximate ALBA norms and cut-off scores. The rule of 100% applies for the first and the second tasks (the sentence repetition and gesture demonstration without problems). The rule of 50% applies for the third and the fourth tasks: gesture and sentence recall (at least 3 out of 6) and their sum as the memory ALBA score (at least 6 [3+3] out of 12). These cut-off points are higher (4+4=8) in more educated or younger individuals.

This is the first report to explore convergent validity with traditional neuropsychological tests. Based on the current results, the ALBA test is predominantly an assessment of short-term and episodic memory. It was significantly associated with different types of memory: immediate, delayed, visual, verbal, and semantic. Moreover, it also reflects other cognitive components: executive function, language, visuospatial skills, and psychomotor speed. Memory is obviously the major component of the ALBA test. In addition, a language part may also be useful in some specific patient groups, such as those with stroke or non-memory neurodegenerative disorders. Impairments may be easily identified and rapidly quantified in the first task, sentence repetition (conduction aphasia or some forms of Broca's non-fluent aphasia, primary progressive aphasia, a logopenic variant of frontotemporal dementia or AD, etc.), or in the second task, gesture demonstration in response to instructions (impaired understanding, Wernicke's fluent aphasia).

The semantic fluency task is a multi-domain task reflecting semantic memory, working memory, and executive function at the same time. Some studies addressing verbal fluency have found a relationship between semantic fluency and memory (anterior temporal regions) and between phonemic fluency and executive functions (frontal regions).21,43–46 Thus, the correlation with semantic fluency may support the convergent validity of the ALBA test.

In summary, the ALBA test involves all relevant cognitive functions. The multi-cognitive nature of the ALBA test is its major advantage for general use and different purposes. It implies that mild deficits in different cognitive domains can be detected using a universal test across all major cognitive functions. Moreover, the high correlation with the functional assessment using the FAQ questionnaire indicates the ecological validity of the ALBA test and addresses the real problems of patients and their caregivers.

The ALBA was only negligibly influenced by sociodemographic factors. Sex showed no influence. Education and age had a small influence on sentence repetition but no influence on gesture demonstration, since all participants, regardless of cognitive status, achieved maximum or near maximum scores. We may assume that gesture and sentence recall would not depend on sociodemographic factors. Age and education had a minimal impact, which was expressed as a change of one point on the total memory ALBA scores for every 20 years of age and for every 10 years of education. Age and education each explain only 6% of the variability in memory ALBA scores. This means that most variability is explained by factors other than age or education. The usual range of years of education in our country is between 8 and 18 years, i.e., it corresponds to a one-point difference in the memory ALBA score. Minor or absent variability in cut-off scores can be expected in countries with lower education levels. Various cognitive reserve changes related to education and age may explain these relationships. In this regard, when compared to the well-known MMSE or MoCA tests, the ALBA test does not require semantic, long-term memory, abstract thinking, orientation in time and space, or calculation skills. Results in these tasks also depend on premorbid knowledge and context (e.g., school abilities, hospital or home setting), which are not necessary for administration of the ALBA test.

We would like to highlight the extraordinary range of memory ALBA scores to quantify the severity of cognitive impairment after only 2–3min of testing. The ALBA test has a rather higher range than similar brief tests (see comparison in Supplementary Table 3). A maximum of 12 points is the highest score quantifying memory functioning among other brief and even longer instruments: the CDT (0), the Mini-Cog (3 words), the MMSE (3 words), and the MoCA (5 words).1,18,25,26 Moreover, the ceiling effect is small for the 2 highest memory ALBA scores (4+18=22%) (Supplementary Fig. 1C), compared to the MMSE (25+32=57%) and the MoCA (24+26=50%), according to data from our previous studies.25,26

Our study has some limitations. First, glasses or binoculars are not universally familiar objects, so these gestures should be replaced by culturally appropriate items, e.g., closing and rubbing eyes. Second, translation of the sentence into other languages might be challenging with a view to preserving the original meaning and the number of words.6 For example, the sentence in the authors’ original language is actually the following: “Grandmother's summer starts with the first morning frost.” If possible, autumn should be translated in a metaphoric way using an appropriate adjective plus “summer” (e.g., verano indio in Spanish, pastırma yazı [“bacon summer”] in Turkish), a verb should mean “to begin/start,” and the translation should keep the words “morning” and “frost”. For example, the Turkish version “Pastırma yazı İlk sabah donlarıyla başlar” fulfilled the criteria for the sentence translation. Third, the main purpose of this article was to introduce and validate the new instrument, and to determine whether the ALBA test can detect MCD in general. It is unclear whether the ALBA can help in differential diagnosis to distinguish between different neurodegenerative disorders, since these were combined into one group in this study. We assume that the ALBA test might detect deficits with different patterns in some neuropsychiatric conditions (e.g., language involvement in frontotemporal dementias, stroke, or depression), which needs to be explored in future studies. Fourth, our validation sample size was relatively small. However, normative data were derived from a sufficiently large cohort. Importantly, the ALBA cut-off scores are from a comparison of 2 groups and were in agreement with those obtained independently in a normative sample. Therefore, the cut-off points were double-checked. Fifth, sensitivity and specificity values were useful for comparing tests. However, they do not provide the likelihood of having a condition when scoring below (or over) the cut-off scores. Predictive values do give this information, and predictive values are affected by prevalence. If 2 groups of the same sample size were defined, then the prevalence would be 50%, which is not possible. Sixth, direct comparisons against other brief instruments were not included in the current report due to space limitations; this will be the subject of future reports.

In conclusion, the newly developed ALBA test, with its 2 subtests divided into 4 tasks, has shown high discriminant and convergent validity, even in patients with only mild cognitive deficits. This simple testing paradigm was associated with a diverse range of tests and cognitive functions.

We performed the test in almost every mildly affected patient at our memory clinic. The ALBA test is used during cognitive screening in pharmacies and by social workers, speech therapists, and other professionals across the country. We are pleased that a Turkish anesthesiologist has included the ALBA test in his research on the influence of anesthesia on cognitive function.

What are the clinical implications of our study? The ALBA has the potential to be an ultra-brief and universal cognitive test useful for cognitive impairment, dementia, and other conditions. The ALBA test and its principles can easily be adapted to other cultures and countries. It can be helpful in various conditions and settings typical of everyday clinical practice and research. It can also be used for widespread or population screening, international migrants, or as a pre-screening tool in clinical trials. Clinicians and other professionals can benefit from the ALBA test, since simple and quick administration and scoring are desirable not only in the cognitive fields of neurology, psychiatry, and geriatrics but also in primary and social care, peri-operative surgery, anesthesiology, pharmacy, and other medical disciplines. COVID-19 is accompanied by a wide range of neurological and neuropsychiatric symptoms, including altered mental status47,48. The very high number of individuals with COVID-19 can be quickly examined using the ALBA test.

An English-language version of the ALBA test can be downloaded from www.abadeco.cz or the developer. An educational video with English subtitles demonstrates the proper administration and scoring with a patient and is available on the Ales Bartos YouTube channel (https://youtu.be/LyCuWc0-Gro). Ales Bartos owns the copyright and makes this test available for free for non-commercial use in clinical practice, education, and research; for other uses, the corresponding author should be contacted for permission.

The ALBA test can be complemented with our another very brief test - the Picture Naming and Immediate Recall (PICNIR).49

FundingThis study was supported by Neuroscience COOPERATIO [207038] from Charles University, Development of research organizations from the Ministry of Health [Kralovske Vinohrady University Hospital, 00064173], and TACR in the Sigma program DC3 [TQ01000332].

Authors’ contributionsAles Bartos developed the ALBA test, designed the study, obtained funds, organized and supervised research assistants to administer tests and collect data, performed the statistical analyses, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Sofia Diondet performed all neuropsychological assessments, performed statistical analyses, and contributed to the manuscript.

Conflict of interestAles Bartos developed the ALBA test. Sofia Diondet has no competing interests to declare.

The authors thank the nurse of Memory Clinic Renata Petrousova for the assistance with data collection and Thomas Secrest for the English editing of the manuscript.