Recent years have seen the emergence of new health problems associated with the development of new technologies. This has led to the creation of the terms “Nintendinitis,” “Wiiitis,” and “Whatsappitis” to refer to tendinitis secondary to the use of Nintendo and Wii consoles and the WhatsApp mobile application.1,2 Cases have also been described of diagnostic uncertainty associated with transient monocular blindness following smartphone use.3,4 As well as causing new disorders, these technologies may also constitute a new, peculiar form of manifestation of classical disorders.

We propose the term “awagraphia” to describe the presentation of agraphia during use of the WhatsApp instant messaging service in a patient with the syndrome of transient headache and neurological deficits with cerebrospinal fluid lymphocytosis (HaNDL).

HaNDL syndrome, also known as pseudomigraine with pleocytosis, is a benign entity whose aetiology is not well understood. Aphasia is a frequent manifestation of this syndrome, in which patients display lymphocytic pleocytosis and self-limited episodes of neurological deficits, which last minutes and usually precede severe headache.

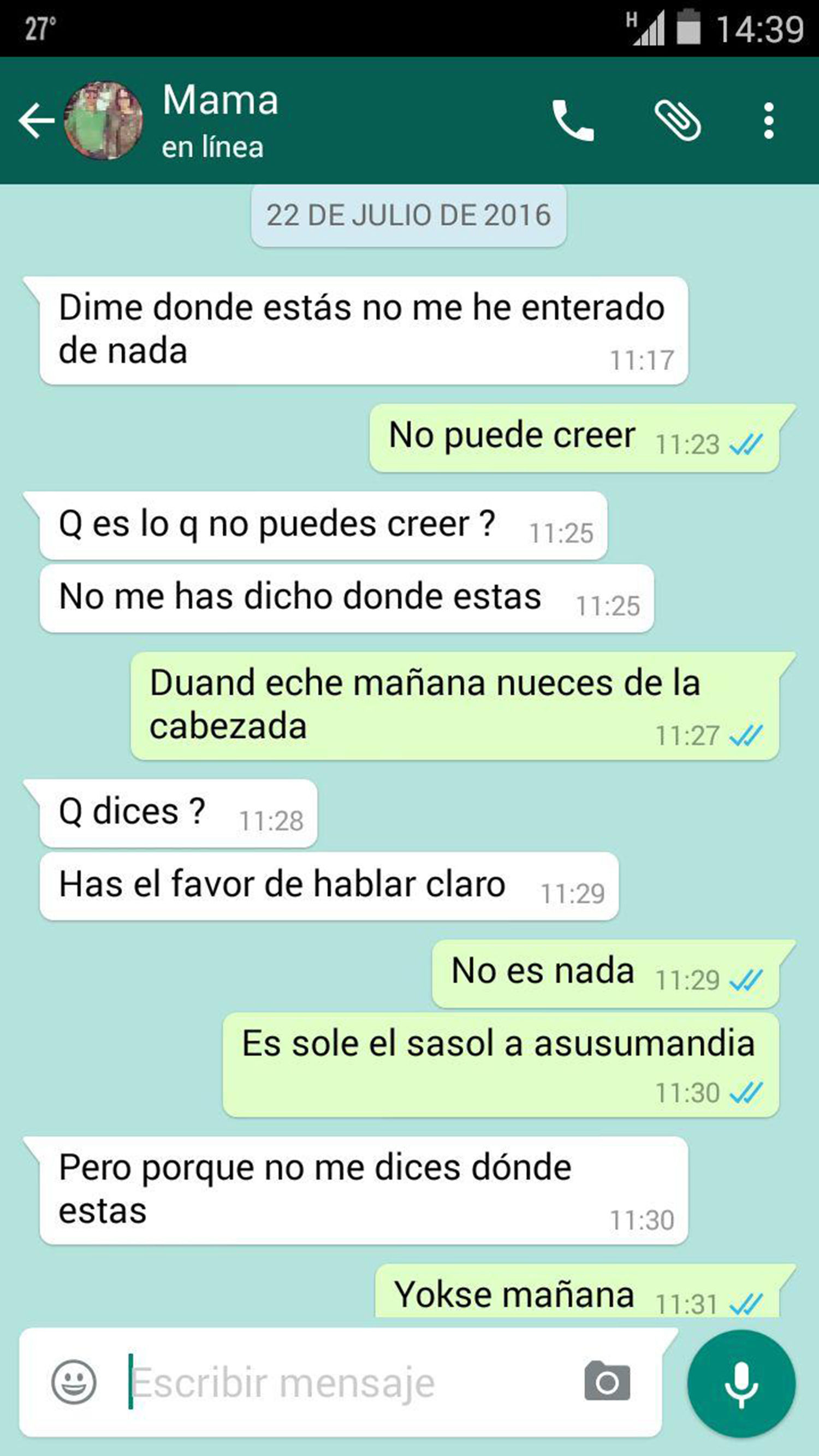

Clinical caseWe present the case of a Spanish man of 26 years of age without history of migraine who presented a self-limited episode of language alteration (agraphia) during a WhatsApp conversation with his mother (Fig. 1), which we colloquially refer to as “awagraphia” to emphasise the unusual form of presentation. It is unclear whether comprehension was preserved, although we do know that oral conversation was not possible, as the patient was taken to the emergency department after speech alterations were noted during a telephone conversation.

By the time of assessment, the neurological deficit had resolved and no abnormalities were detected, although the patient reported intense, pulsatile, holocranial headache accompanied by nausea, which had lasted several hours. The patient's family showed us the WhatsApp conversation, and insisted that several minutes earlier “we couldn’t understand anything he was saying.” Blood analysis and a head CT study yielded normal results.

The patient reported similar episodes of headache of several hours’ duration in the previous 20 days, for which he had consulted twice and which had been treated symptomatically, without assessment by a neurologist. One previous attack had been preceded by an episode of hemibody sensory disturbance of several minutes’ duration, and another had been accompanied by blurred vision, although no significance had been attributed to these symptoms. Between episodes, the patient was asymptomatic.

Blood tests included a complete blood count; kidney and liver biochemistry; a coagulation test; an autoimmunity study; and serology for HIV, hepatitis B and C viruses, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus. We also performed a brain MRI study with intravenous contrast administration, and an electroencephalography. All test findings were normal. Analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid revealed predominantly mononuclear pleocytosis and elevated protein levels (130leucocytes/mm3, 99% mononuclear; 0.59mg/L protein), leading to a diagnosis of pseudomigraine with pleocytosis.

This case demonstrates the way in which the everyday use of new technologies can give rise to new forms of presentation of neurological symptoms. According to the information collected from the patient and his family in the clinical history interview, we may infer that he presented jargon aphasia with neologisms, although we were unable to assess speech as symptoms had resolved before he arrived at the emergency department. Similarly, the screen capture of the WhatsApp conversation (Fig. 1) shows jargon agraphia with neologisms. As we do not know what the patient wanted to express during the episode, we cannot conclude that he presented paragraphia. Insufficient data are available to identify the type of aphasia the patient presented during the episode.

In any case, agraphia was the sentinel symptom that triggered the search for specialised medical attention in a clinical context that had previously not been considered relevant. The expression of classical symptoms through new technologies may inform the differential diagnosis of language disorders, which can be difficult when symptoms are described by family members and not observed directly by the neurologist. In this case, we were able to recognise and characterise the disorder, with the added peculiarity of its form of presentation, enabling us to establish a working diagnosis, which was subsequently confirmed.

Please cite this article as: Iglesias Espinosa M, Fernández Pérez J, Ramírez García T, Serrano Castro PJ. Awagrafia. Neurología. 2020;35:69–70.

This case report was presented in poster format at the 39th Annual Meeting of the Andalusian Society of Neurology (October 2016).