Os odontoideum is a bone malformation in which there is a separation between the odontoid process and the body of the axis (C2). It may cause atlantoaxial dislocation, presenting with severe clinical symptoms, including cervical pain, torticollis, headache, neurological symptoms secondary to spinal cord or vertebral artery compression, and even sudden death.

Further research is necessary to accurately determine the aetiology and treatment of this disorder. Likewise, population studies should be conducted to estimate its prevalence.

We present the case of a patient with cervical compressive myelopathy secondary to atlantoaxial dislocation in the context of os odontoideum.

Clinical caseOur patient was a 25-year-old woman with no relevant medical history, including no history of head or neck trauma, and a low-risk job. She had a 3-year history of progressive difficulty walking due to subjective left-sided weakness but showed no dysphagia or other symptoms. The physical examination revealed deep tendon reflexes, ankle clonus, and Babinski sign present on the left side of her body. We found no skin hyperlaxity, joint hypermobility, or alterations in temperature and pain sensitivity.

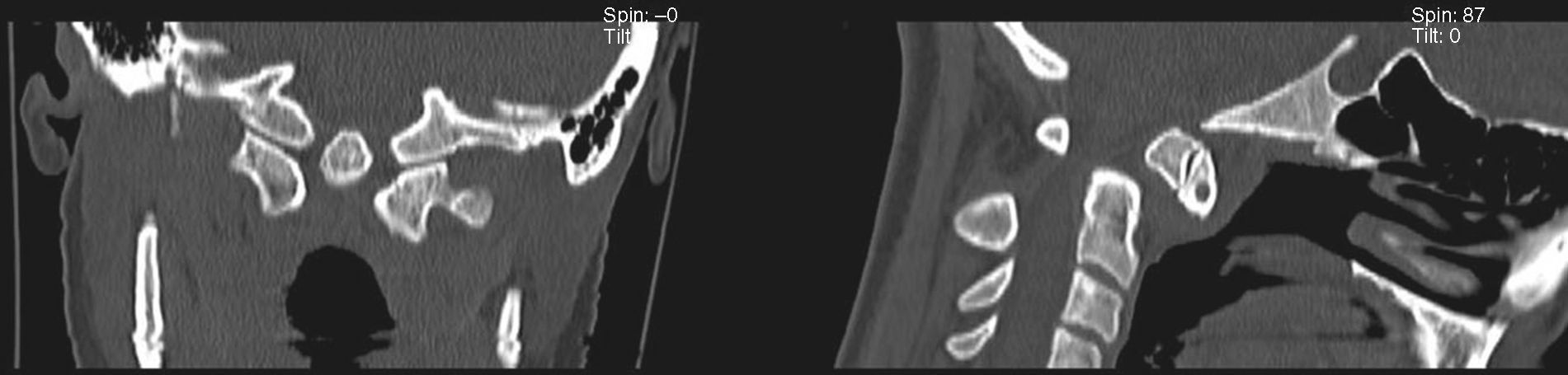

The complementary tests found no signs of either rheumatic disease or disorders of calcium and phosphate metabolism. A neck MRI scan displayed previous atlantoaxial dislocation, which compressed the spinal cord at the cervicomedullary junction (Fig. 1). A complementary CT scan of the cervical spine revealed os odontoideum (Fig. 2). The figures show the os odontoideum protruding above the Chamberlain line, an imaginary line joining the back of the hard palate with the opisthion on a lateral view of the cervical spine. As no other bone lesions can be seen, this finding indicates basilar invagination.

The patient underwent occipitocervical arthrodesis and a bilateral C1 laminectomy; as a result of the intervention, left-sided weakness subsided.

DiscussionThere are 2 widely accepted hypotheses about the aetiology of os odontoideum. The first suggests that the anomaly is secondary to an odontoid synchondrosis fracture before the synchondrosis fuses (by the age of 5 or 6)1; during growth, the alar ligaments progressively pull the odontoid process fragment, which detaches from the base of the axis but keeps receiving nutrients via the blood supply from the apical arcade (in some series, trauma was the aetiology in up to 56% of the patients).2 The second hypothesis proposes that os odontoideum has a congenital origin, as may be the case in our patient, since the CT scan of the cervical spine revealed the presence of basilar invagination. The presence of os odontoideum has been described in identical twins3 as well as in families, suggesting an autosomal dominant pattern.4,5 Some researchers have found genes associated with the disease, a few of which are linked to morphogenesis and bone maintenance. Between twins with os odontoideum and a control group, Straus et al.6 identified differences in the expression of 213 genes, and also found increased expression of the genes MMP8, KIT, HIF1A, CREB3, PWHAZ, TGFBR1, NFKB2, FGFR1, IPO8, STAT1, COL1A1, and BMP3 in a group of patients with os odontoideum.

Depending on the position of the odontoid process fragment, os odontoideum may be classified as orthotopic, when the fragment is in its anatomical position, or dystopic, when it is displaced (as in our case). Dystopic os odontoideum usually presents with a narrowing of the craniocervical junction and is the type most frequently associated with atlantoaxial dislocation.

Clinical expression of os odontoideum is variable and may be divided into 4 categories: 1) asymptomatic (even in cases of atlantoaxial dislocation demonstrated by imaging techniques), 2) local symptoms (cervical pain, torticollis, headache), 3) other symptoms associated with cervical compressive myelopathy (which may be transient, static, or progressive),7 and 4) symptoms secondary to vertebrobasilar ischaemia.8,9 Cases of sudden death have also been reported.

Diagnosis is based on imaging findings and cervical radiographs usually suffice.9 However, CT and MR images are more precise and also show spinal cord involvement. In the case presented here, and despite their diagnostic capacity, no cervical flexion-extension images were taken as performing them could have been perjudicial to our patient's clinical state.

Currently recommended treatments for os odontoideum are supported by class III medical evidence only.9 Asymptomatic patients with no atlantoaxial dislocation may be treated conservatively with clinical and radiological follow-up: although most series describe no progression, some patients may present atlantoaxial dislocation at later stages.10,11 Surgery, especially posterior C1-C2 fixation and arthrodesis, is recommended for patients with neurological symptoms and atlantoaxial dislocation.9,12 Surgery is also recommended for asymptomatic patients with atlantoaxial dislocation since minor cervical trauma may result in spinal cord damage,2,9,10 although in some studies, patients who did not undergo surgery displayed no symptoms during follow-up.1,13

In our case, congenital os odontoideum, as indicated by the presence of basilar invagination, manifested as left-sided weakness and pyramidal signs which were secondary to spinal cord compression following anterior atlantoaxial dislocation.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Tejada Meza H, Modrego Pardo P, Gazulla Abio J. Mielopatía cervical como forma de presentación de un os odontoideo. Neurología. 2016;31:278–279.