Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) is characterised by clinical and radiological signs of vasogenic oedema, which are generally reversible. Due to the lack of established diagnostic criteria, the condition is underdiagnosed, and we must be alert in the event of potential trigger factors.1

Onset can be acute or subacute, and is usually progressive; most patients present impaired awareness, visual alterations, and/or seizures. Association with acute hypertension is very frequent, and may play a role in pathogenesis. Prognosis is mainly determined by potential causes of PRES, such as autoimmunity, sepsis, eclampsia, and various cytotoxic substances.1

Immunotherapy, an increasingly common treatment for several types of cancer, is one predisposing factor. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) have been associated with a range of neurological adverse effects of the regulation of T cell activity.2

We present a patient who developed PRES following treatment with pembrolizumab, presenting with headache, reduced level of consciousness, and cortical blindness associated with Anton syndrome.

The patient was a 56-year-old woman with stage IV adenocarcinoma of the lung, diagnosed 3 months earlier. She was a former smoker and had recent history of pulmonary embolism. She received first-line treatment with carboplatin, pemetrexed, and pembrolizumab, with apparently good tolerance. Three weeks after the first dose, she began presenting poor blood pressure control, chest pain, and intense holocranial pressing headache, with no other evidence of neurological involvement. Oncological treatment was continued, and the next day she received the second cycle of treatment, following the same schedule; headache persisted, and she also presented nausea and systolic blood pressure of approximately 180 mm Hg. The same day, she complained of vision loss in the right hemifield, progressing to the entire visual field over a period of 24 hours. The patient’s family observed a degree of confabulation regarding her visual perception, and indifference to her deficits and clinical situation. At the same time, she continued to present arterial hypertension, which was refractory to treatment but labile, with at least one episode of hypotension (systolic blood pressure of 80 mm Hg) secondary to antihypertensive treatment, associated with reduced level of consciousness.

On the fifth day after onset of neurological symptoms, she was alert, attentive, and cooperative, although she was disoriented to time, place, and person. She was able to turn her gaze to voice, but in the visual examination she was unable to count fingers in all areas of the visual field, and did not recognise basic images. She did not acknowledge these deficits and presented confabulation regarding their content. Pupils were isochoric and normoreactive, and ocular motility was preserved. She did not present nystagmus in any position. Examination revealed no other signs of cranial nerve involvement. The motor examination revealed distal weakness in the right hand (4/5 on the Medical Research Council scale). Stretch reflexes were present symmetrically, with no increase in the reflexogenic zone. Plantar reflexes were flexor. The patient had no sensory complaints. She did not present meningism. Gait and appendicular dysmetria were not examined due to the vision loss.

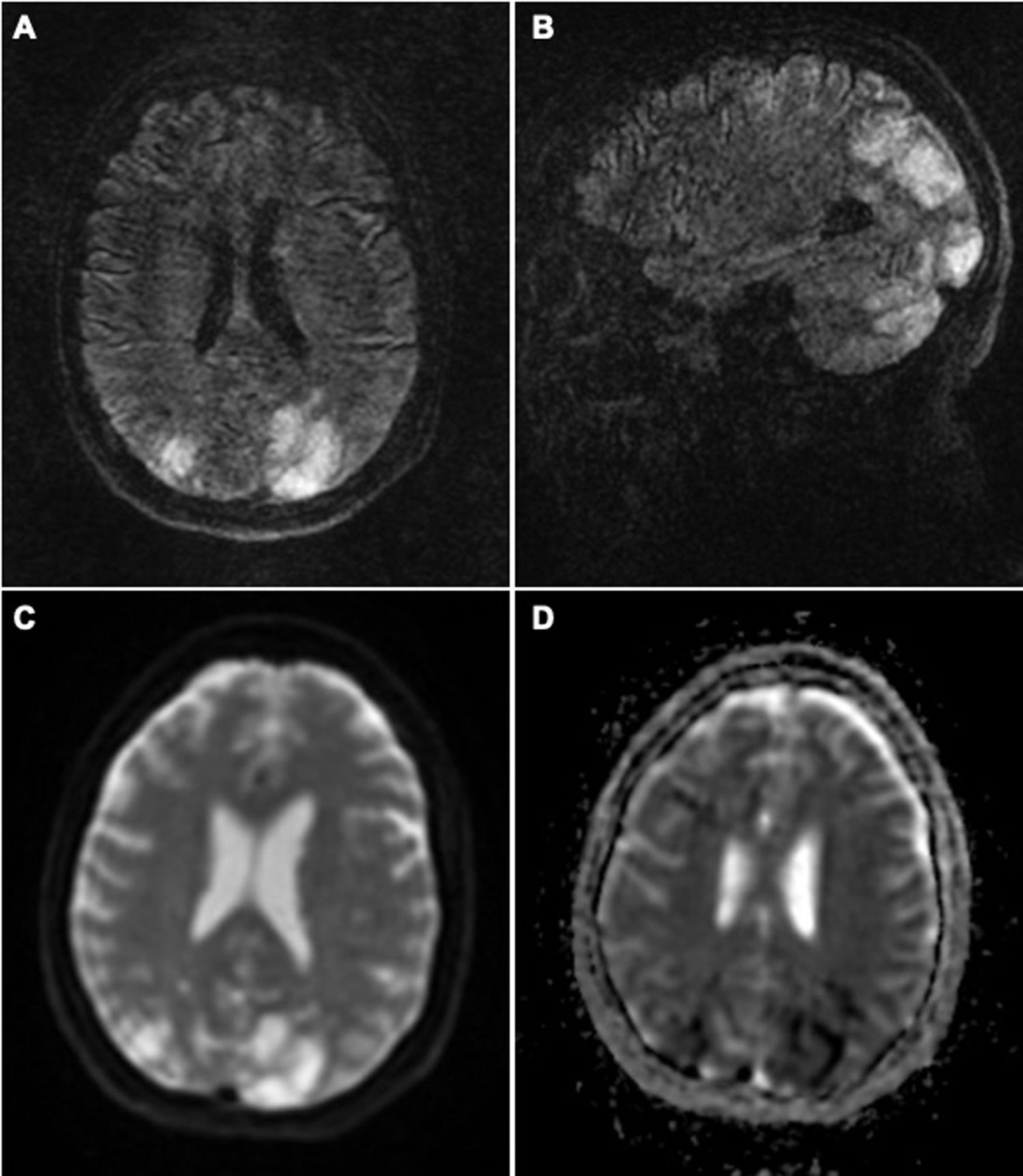

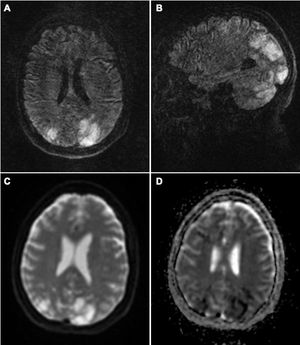

Brain MRI revealed T2-FLAIR hyperintensities in both cerebellar hemispheres, thalami, and parieto-occipital lobes, and border zones. Some lesions presented diffusion restriction (Fig. 1). Blood analysis showed glycaemia and ion levels within normal ranges, and no other significant alterations.

Brain MRI study: axial (A) and coronal (B) T2-FLAIR sequences showing hyperintense lesions in both cerebellar hemispheres and parieto-occipital lobes, predominantly on the left side, which do not correspond to the territory of a large vessel. DWI sequences (C) show diffusion restriction in some of these lesions, with low ADC values (D). All these signs are suggestive of severe PRES secondary to established infarction.

On day 6 after onset, the patient died due to acute pulmonary insufficiency associated with lymphangitis carcinomatosa.

Regarding the treatment she was administered, it should be noted that pembrolizumab is an ICI that, like nivolumab, targets programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1). Other drugs target CTL-4 (eg, ipilimumab) or PD-L1 (eg, durvalumab).3 Among neurological adverse reactions to the drug, neuromuscular symptoms are particularly relevant on account of their severity.4 However, PRES is another adverse event that should be taken into consideration, and has previously been associated with some ICIs.2

Our patient’s clinical and radiological signs are compatible with PRES; the cytotoxic oedema observed in the neuroimaging study indicated poor prognosis.1 The lesions to border zones, which are uncharacteristic in this syndrome, may be explained by the episodes of symptomatic hypotension secondary to treatment for the hypertensive crises, together with impaired vascular self-regulation in the brain due to the vasoconstriction syndrome.

Two main hypotheses, which are not necessarily mutually exclusive, have been proposed to explain the pathophysiology of PRES. According to the first, blood pressure rising above the limits of cerebral self-regulation leads to hyperperfusion of the tissue, causing vasogenic oedema. Cerebral hyperperfusion would contribute to blood-brain barrier dysfunction, causing extravasation of plasma and macromolecules. This “hyperperfusion theory” is supported by the high or fluctuating blood pressure values observed in the majority of patients. The posterior territory is particularly vulnerable, given the lower density of sympathetic innervation in this region. However, up to 30% of patients with PRES present normal or only slightly elevated blood pressure values. The second theory proposes that the syndrome is triggered by endothelial dysfunction caused by circulating endogenous toxins (as in eclampsia or sepsis) or exogenous toxins (eg, chemotherapy or immunosuppressants). A variant of this “toxic theory” is the “toxic-immunogenic theory” according to which the trigger factor is excessive production of proinflammatory cytokines, resulting in endothelial activation, the release of vasoactive substances, and oedema.1 This mechanism would explain cases of PRES associated with autoimmune disorders, and seems to be the most likely hypothesis in our patient.

Some tumours can express proteins that bind to PD-1 on T cells, inhibiting the immune system’s capacity to attack tumour cells. Inhibition of PD-1 by pembrolizumab, a humanised antibody, enables reactivation of T cells, which are then able to target cancer cells. However, it also promotes increased autoimmune responses. In the case of PRES, this immune cascade would cause endothelial damage with definitive disruption of vascular integrity, resulting in cerebral oedema.4,5

The only patient reported to date with PRES associated with pembrolizumab had been treated with ipilimumab in the preceding months; several cases have been reported in association with this drug.5 While cases of PRES have been reported in association with platins and pemetrexed, onset usually occurs after a longer interval following the last administration of the drug.6 There is more evidence of a link between PRES and monotherapy with ICIs, after a single dose, with onset generally occurring in the weeks following treatment,7 although we cannot rule out a potential cumulative effect involving the other 2 chemotherapeutic drugs in our patient.

Due to the death of the patient, it was not possible to perform a follow-up neuroimaging study to observe the degree of resolution. However, given the association with combination therapy with pembrolizumab in our patient, which was started 3 weeks earlier, the case has been notified for pharmacovigilance purposes.

We consider it important to report this case of a rarer neurological adverse event associated with immunotherapy; such events may become more frequent if these drugs are used in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents. Given their increasingly widespread use to treat different types of cancer, it is essential to raise awareness of these adverse reactions among both oncologists and neurologists.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Lambea-Gil Á, Sancho-Saldaña A, Caldú-Agud R, García-Rubio S. Encefalopatía posterior reversible asociada a combinación con pembrolizumab. Neurología. 2021;36:548–550.