To describe the experience of physicians and patients in the Telepsychiatry programme at the University of Antioquia's Faculty of Medicine in the first 12 months after its implementation in eight towns across Antioquia.

MethodologyA descriptive study involving the evaluation of 111 patients during the programme's first year. An instrument was designed to evaluate patients' satisfaction and the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) was used to evaluate the health professionals' satisfaction.

Results111 patients were seen on 340 occasions. 70 out of the 111 patients (63.1%) were seen by Telepsychiatry at least twice in the first year of implementation. A sample of 38 patients (34%) was used to evaluate their experience, of which 94.7% said their problem had been solved and 100% were highly satisfied. Nine health professionals took part in the programme, who agreed that the technology was useful and easy to use. They also stated that they wanted to continue using it.

ConclusionHealth systems across the globe have failed to provide an adequate response to the mental health burden. Therefore, strategies such as telepsychiatry are considered an ideal treatment modality to give patients living in remote locations the specialised attention that they need.

Describir la experiencia que han tenido los médicos y pacientes del programa de Telepsiquiatría de la Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad de Antioquia en los primeros 12 meses de su implementación en 8 municipios del departamento.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo, que incluyó a 111 pacientes atendidos durante el primer año. Se diseñó un instrumento para evaluar la satisfacción de los pacientes y se empleó el instrumento de aceptación de tecnología para evaluar la de los profesionales de la salud.

ResultadosSe realizaron 340 atenciones durante ese periodo a 111 pacientes; 70 (63,1%) de ellos recibieron al menos 2 atenciones por telepsiquiatría en el primer año. Se evaluó la experiencia en una muestra de 38 pacientes (34%), quienes manifestaron la resolución del problema (94,7%) y una satisfacción alta (100%). En el programa participaron 9 profesionales de la salud, que estuvieron de acuerdo en que la tecnología es útil y fácil de usar y tienen la intención de seguir usándola.

ConclusionesLos sistemas de salud de todo el mundo no han dado una respuesta adecuada a la carga de trastornos mentales; por esto, estrategias como la telepsiquiatría se consideran una modalidad de atención ideal para personas que viven en lugares remotos y tienen dificultad de acceso a los servicios de salud especializados, con adecuada aceptación.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), around 450 million people worldwide suffer from mental and behavioural disorders. One in 4 people will suffer from one or more of these disorders in their lifetime,1 and 5/10 of the leading causes of disability and premature death in the world are due to mental illness. By 2020, mental health problems are expected to be the most common health problems in the world, above cardiovascular diseases and cancer.2

In Colombia, according to the 2015 Encuesta Nacional de Salud Mental (National Health Survey [ENSM]), 82.2% of the Colombian population seeks care from healthcare institutions and healthcare professionals for reasons related to mental illnesses3; however, only 38.5% of adults who requested some type of mental health care received it.3 Mental health, like other aspects of health, can be affected by a number of socioeconomic factors that must be addressed through comprehensive promotion, prevention, treatment and recovery strategies.4 Based on this, the ENSM determines that modalities such as telemedicine and other strategies should be implemented to facilitate interaction between primary care professionals and specialists, and in turn increase the opportunity for and the continuity and quality of mental health care.

Telemedicine is the practice of medical care with the help of interactive information and communication technologies (ICT) involving sound, images and data; it includes the provision of medical care, consultations, diagnosis and treatment, as well as training and transfer of medical data.5 This strategy is gradually advancing in Latin America and the Caribbean,6 and helps to reduce the deep gaps in access and quality in healthcare. Thanks to ICT, it is possible to bring healthcare — often specialised — to places where there is none and provide distance training to healthcare teams distributed throughout the immense and rugged terrain.2

Law 1419 of 2010 establishes telemedicine as part of the General System of Social Security in Health in Colombia, and defines as the provision of distance healthcare services that use ICT.7

Certainly not oblivious to these advancements, the Faculty of Medicine of the Universidad de Antioquia [University of Antioquia] has ventured into the field of telehealth in recent years, and with the use of ICT tools, it has developed new services and care models that provide alternative solutions to healthcare problems in Antioquia, with the possibility of reproducing them in other regions of the country. That is why LivingLab Telesalud and the Department of Psychiatry of the Faculty of Medicine set up the medical psychiatry department under the telemedicine modality, from which a care programme was implemented that contributes to academic practice among medical students (residents) and allows the psychiatrist, in a virtual setting, to promptly and suitably address the needs for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients residing in remote areas of the department.

It is also very important to take into account the support that can be offered to healthcare professionals who are part of basic care teams in remote locations, as this improves decision-making and referral quality, decreases diagnostic variability and makes it possible to increase safety and reliability among these professionals through continuous training.8

The objective of this study is to report the experience of doctors and patients with the Telepsychiatry programme developed by the Faculty of Medicine of the Universidad de Antioquia in 8 municipalities of the department of Antioquia in the first 12 months of its implementation.

MethodsA descriptive, cross-sectional observational study was conducted for the purpose of quantitatively presenting the perception of health professionals and patients who participated in the Telepsychiatry programme of the Universidad de Antioquia for the first year after its implementation. The eligible population was considered to be patients referred from the first level of care to outpatient psychiatry; patients who received care from Health Service Providers that had an agreement with the Universidad de Antioquia for this programme, between August 2016 and August 2017, and who signed the informed consent form for care under the telemedicine modality were enrolled.

Study data were collected using the medical record, a technology acceptance instrument validated by Paul J. Hu9 to evaluate the experience of health professionals, and a survey created by the team of researchers to determine the experience of patients.

For the characterisation of the population, all patients and healthcare professionals present in the year under study were enrolled. For the experience evaluation, 100% of the healthcare professionals who were there during the study period and a convenience sample of 38 patients (34%) who participated in the Telepsychiatry programme were included. The information was entered into a database for tabulation and descriptive statistical analysis with absolute values and percentages for categorical variables, and the mean ± standard deviation or the median [interquartile range] for quantitative variables, according to the distribution of the data. The R programming language was used for data processing.

The research was classified as minimal risk; however, all applicable provisions for research with human beings were taken into account.10 All patients and healthcare professionals who participated in the experience evaluation were previously asked for verbal informed consent.

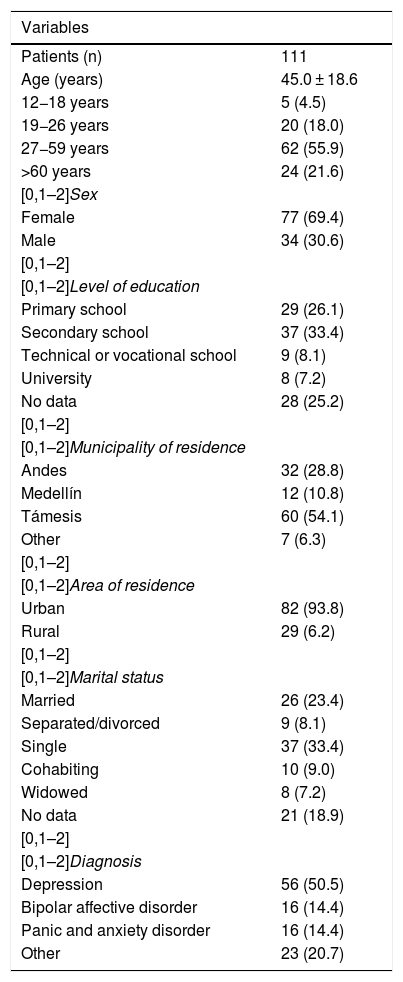

ResultsPatient characteristicsTable 1 shows the sociodemographic and clinical data of the 111 patients treated under the telepsychiatry modality in the first year of operation of the programme at the Universidad de Antioquia. In total, 340 visits were made during this period, with a minimum of 1 consultation per patient and a maximum of 9 visits; 70 patients (63.1%) received at least 2 telepsychiatry visits in the first year.

Sociodemographic and clinical variables of the patients seen by telepsychiatry.

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 111 |

| Age (years) | 45.0 ± 18.6 |

| 12−18 years | 5 (4.5) |

| 19−26 years | 20 (18.0) |

| 27−59 years | 62 (55.9) |

| >60 years | 24 (21.6) |

| [0,1–2]Sex | |

| Female | 77 (69.4) |

| Male | 34 (30.6) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Level of education | |

| Primary school | 29 (26.1) |

| Secondary school | 37 (33.4) |

| Technical or vocational school | 9 (8.1) |

| University | 8 (7.2) |

| No data | 28 (25.2) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Municipality of residence | |

| Andes | 32 (28.8) |

| Medellín | 12 (10.8) |

| Támesis | 60 (54.1) |

| Other | 7 (6.3) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Area of residence | |

| Urban | 82 (93.8) |

| Rural | 29 (6.2) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Marital status | |

| Married | 26 (23.4) |

| Separated/divorced | 9 (8.1) |

| Single | 37 (33.4) |

| Cohabiting | 10 (9.0) |

| Widowed | 8 (7.2) |

| No data | 21 (18.9) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Diagnosis | |

| Depression | 56 (50.5) |

| Bipolar affective disorder | 16 (14.4) |

| Panic and anxiety disorder | 16 (14.4) |

| Other | 23 (20.7) |

Unless otherwise indicated, values are expressed in terms of n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

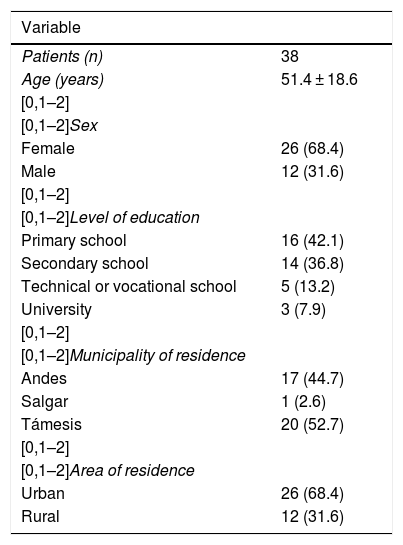

The experience evaluation was performed on a sample (34.2%) of the population seen in the first year. Table 2 shows the characterisation of the surveyed population. Of the 38 patients, the majority were women (68.4%) and the most common age group (57.9%) was that of adults (27−59 years of age). Most of the patients (68.4%) resided in rural areas of the municipalities included in the evaluation.

Sociodemographic characterisation of the patients surveyed on the experience.

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 38 |

| Age (years) | 51.4 ± 18.6 |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Sex | |

| Female | 26 (68.4) |

| Male | 12 (31.6) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Level of education | |

| Primary school | 16 (42.1) |

| Secondary school | 14 (36.8) |

| Technical or vocational school | 5 (13.2) |

| University | 3 (7.9) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Municipality of residence | |

| Andes | 17 (44.7) |

| Salgar | 1 (2.6) |

| Támesis | 20 (52.7) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Area of residence | |

| Urban | 26 (68.4) |

| Rural | 12 (31.6) |

Unless otherwise indicated, values are expressed in terms of n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

It was found that 20 patients (52.6%) had been seen more than twice by the telepsychiatry department and only 9 (23.7%) had attended a single visit.

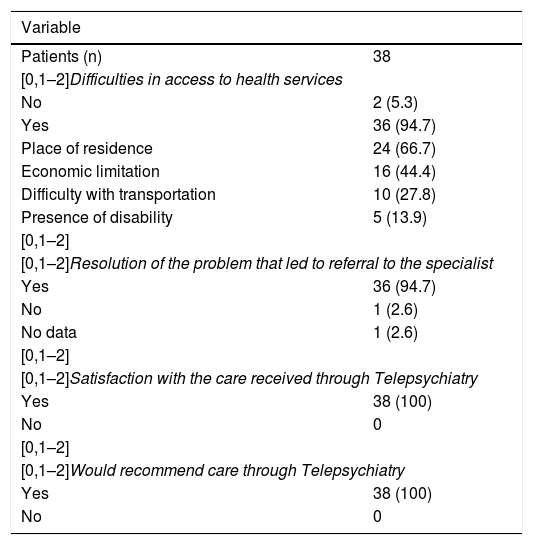

Table 3 shows the survey results. An open question was included in the questionnaire, requesting an opinion, suggestion or comments, which only 17 patients answered. The majority (82.3%) were satisfactory comments; 1 person (5.9%) reported problems with medication delivery management on the part of the healthcare provider and 2 (11.8%) indicated that they would prefer an appointment in person, although they did not give any explanations or make any complaints.

Patient survey results.

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 38 |

| [0,1–2]Difficulties in access to health services | |

| No | 2 (5.3) |

| Yes | 36 (94.7) |

| Place of residence | 24 (66.7) |

| Economic limitation | 16 (44.4) |

| Difficulty with transportation | 10 (27.8) |

| Presence of disability | 5 (13.9) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Resolution of the problem that led to referral to the specialist | |

| Yes | 36 (94.7) |

| No | 1 (2.6) |

| No data | 1 (2.6) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Satisfaction with the care received through Telepsychiatry | |

| Yes | 38 (100) |

| No | 0 |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Would recommend care through Telepsychiatry | |

| Yes | 38 (100) |

| No | 0 |

Unless otherwise indicated, values are expressed in terms of n (%).

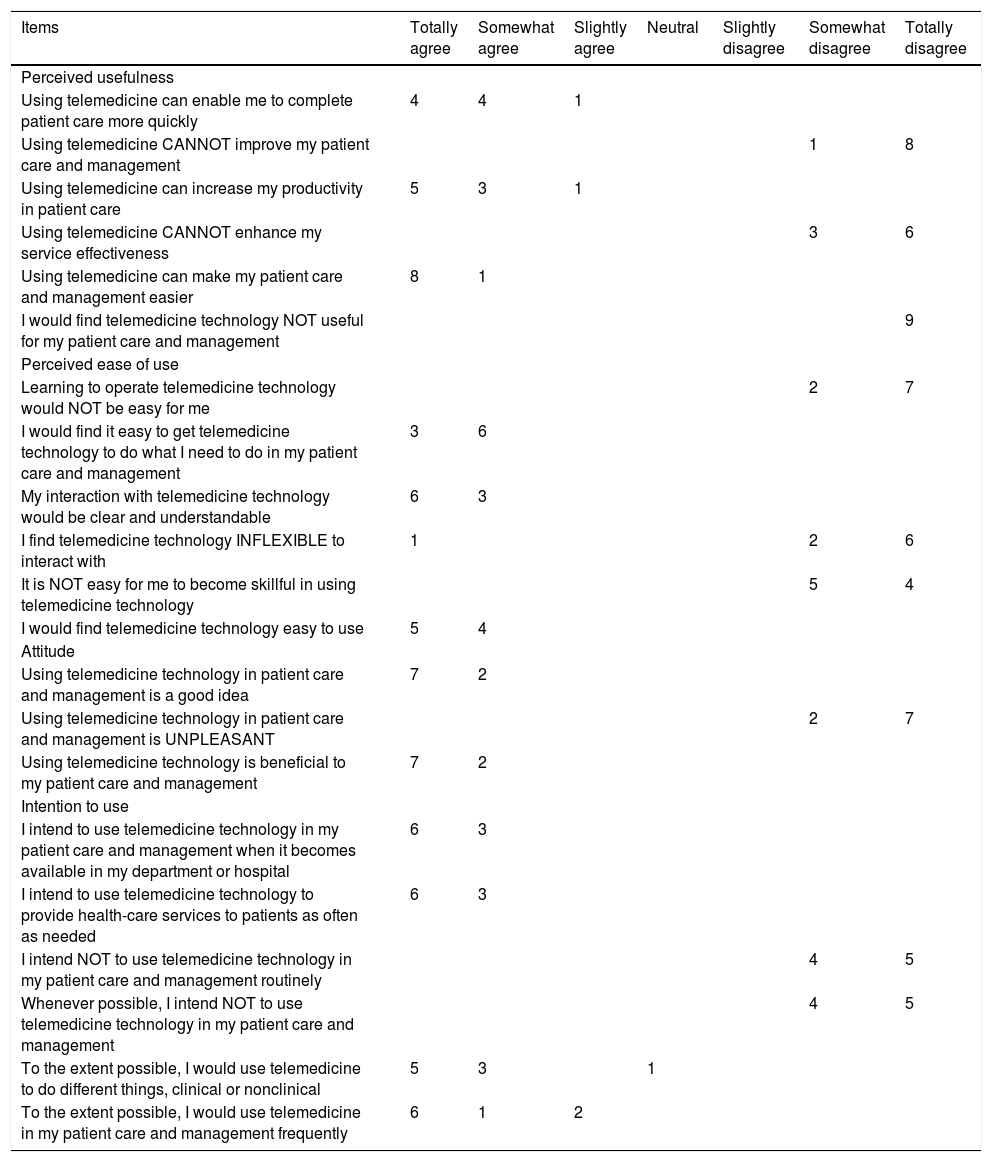

The experience evaluation was performed in 9 healthcare professionals who participated in the care of the 111 patients: 6 psychiatry residents (66.7%), 2 psychologists (22.2%) and 1 psychiatrist (11.1%). Four dimensions were evaluated, with positive results: usefulness, ease of use, attitude and intention to use. Participants agreed that the technology is useful and easy to use and they intend to continue using it (annex).

DiscussionThis study found that the most prevalent diseases were depression and anxiety disorders (among them, panic disorder), in accordance with that reported worldwide, where the mental illnesses with the highest prevalence in the general population are anxiety and mood disorders.4 When the medical records were reviewed, it was noted that the vast majority of the patients who participated in the study had never been evaluated by a psychiatrist, because they had not been referred from the healthcare facility for evaluation by this speciality or due to difficulties in access to a specialised visit. With Telepsychiatry, it was possible to improve the opportunity for and access to healthcare services, which may have had a positive impact on the quality of life of patients and their families.

A systematic review on the main results in Telepsychiatry11 found that the majority of patients and healthcare personnel were satisfied with videoconference care and that it is comparable to face-to-face care; however, they were concerned about the data confidentiality and the limited capacity to respond to an emergency. Regarding patient satisfaction, the studies reported high satisfaction; out of 31 studies, 23 reported good to excellent satisfaction, while the other 7 had mixed reactions. Similarly, a study conducted in the United States12 found high satisfaction among participating patients, even though half of the team of psychiatrists believed that satisfaction with the telemedicine team was not so high. The results of our showed high satisfaction among both patients and health professionals, consistent with the results in the literature.

Although this study found great satisfaction among the healthcare personnel involved in the programme, it was noted that the first level of care has been received more widely by psychologists than by physicians, who showed great resistance to change, possibly due to organisational problems at each hospital preventing them from becoming actively involved in the programme. To break down these organisational and human barriers in the implementation of telemedicine programmes, the healthcare model must be redesigned, existing roles must be redefined and new professional profiles must be created. In addition, staff must be included and trained in the new project so that they feel that they are a part of it, and roles must be redistributed so that staff do not feel overloaded with work and can easily incorporate it into their usual practice. Such things will help to make these programmes sustainable.13

Only one published telepsychiatry study in Colombia was found. This study, conducted in Manizales, evaluated the cost-effectiveness of synchronous versus asynchronous telepsychiatry for people with depression deprived of freedom and found that, on average, the asynchronous modality is more cost-effective.14 However, local studies are needed on the implementation and sustainability of telepsychiatry programmes that have begun to be developed. These programmes, though few in number, can provide very valuable information for the development of new projects and for decision-making.

Regarding operations, there were no technological barriers to the implementation of our programme because the LivingLab laboratory had already gone ahead to work in each municipality, training healthcare personnel in the management of the telemedicine platform and running a dedicated fibre-optic Internet connection; 123 municipalities in the department already have this connection. Technicians at each institution should have the necessary training to solve day-to-day problems, and the telepsychiatry team must be available to help them solve these problems. In addition, technological tools should be easy to use, friendly, accessible, flexible and adapted to the needs of the organisation.

ConclusionsToday, telehealth is recognised as a tool that responds and adapts to the needs presented in the population in terms of health and its determinants. This synchronous teleconsultation programme for psychiatry enabled a significant number of patients with mental illness in rural areas of the department of Antioquia to be seen and have their condition duly diagnosed and treated. Satisfaction among both healthcare personnel and patients was been high; only 2 patients would prefer to be seen in person, but by our team. Although in many studies there is concern about the quality of the doctor-patient relationship through videoconference, this was not a drawback in our experience, since a suitable doctor-patient relationship could be developed.

Health systems around the world have not responded suitably to the burden of mental disorders. For this reason, strategies such as telepsychiatry are considered an ideal care modality for people who live in remote places and have difficulty in accessing specialised health services.

FundingNo funding was received for the conduct of this study.

Conflicts of interestNone.

| Items | Totally agree | Somewhat agree | Slightly agree | Neutral | Slightly disagree | Somewhat disagree | Totally disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived usefulness | |||||||

| Using telemedicine can enable me to complete patient care more quickly | 4 | 4 | 1 | ||||

| Using telemedicine CANNOT improve my patient care and management | 1 | 8 | |||||

| Using telemedicine can increase my productivity in patient care | 5 | 3 | 1 | ||||

| Using telemedicine CANNOT enhance my service effectiveness | 3 | 6 | |||||

| Using telemedicine can make my patient care and management easier | 8 | 1 | |||||

| I would find telemedicine technology NOT useful for my patient care and management | 9 | ||||||

| Perceived ease of use | |||||||

| Learning to operate telemedicine technology would NOT be easy for me | 2 | 7 | |||||

| I would find it easy to get telemedicine technology to do what I need to do in my patient care and management | 3 | 6 | |||||

| My interaction with telemedicine technology would be clear and understandable | 6 | 3 | |||||

| I find telemedicine technology INFLEXIBLE to interact with | 1 | 2 | 6 | ||||

| It is NOT easy for me to become skillful in using telemedicine technology | 5 | 4 | |||||

| I would find telemedicine technology easy to use | 5 | 4 | |||||

| Attitude | |||||||

| Using telemedicine technology in patient care and management is a good idea | 7 | 2 | |||||

| Using telemedicine technology in patient care and management is UNPLEASANT | 2 | 7 | |||||

| Using telemedicine technology is beneficial to my patient care and management | 7 | 2 | |||||

| Intention to use | |||||||

| I intend to use telemedicine technology in my patient care and management when it becomes available in my department or hospital | 6 | 3 | |||||

| I intend to use telemedicine technology to provide health-care services to patients as often as needed | 6 | 3 | |||||

| I intend NOT to use telemedicine technology in my patient care and management routinely | 4 | 5 | |||||

| Whenever possible, I intend NOT to use telemedicine technology in my patient care and management | 4 | 5 | |||||

| To the extent possible, I would use telemedicine to do different things, clinical or nonclinical | 5 | 3 | 1 | ||||

| To the extent possible, I would use telemedicine in my patient care and management frequently | 6 | 1 | 2 |

Please cite this article as: Pérez DCM, García AMA, Carrillo RA, Cano JFG, Cataño SMP. Telepsiquiatría: una experiencia exitosa en Antioquia, Colombia. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2020;49:239–245.