Although complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use among patients with rheumatic diseases is extensive, discussions regarding these treatments occur rarely in the rheumatology setting, directly affecting the physician–patient relationship (PPR).

ObjectivesThe aim of this study was to evaluate the association between patient-physician relationship and complementary and alternative medicine use. As secondary objectives, to describe the patient’s perspective towards CAM use and estimate the prevalence of CAM treatments used in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Methods and materialsA descriptive cross-sectional survey was conducted, in which CAM use and physician–patient relationship were assessed by self-reported validated questionnaires (I-CAM-Q and PDRQ-9, respectively).

ResultsThe study included a total of 246 outpatients of a tertiary care hospital. There were no significant differences between CAM users vs. non-users, or informers vs. non-informers in terms of physician–patient relationship measured by PDQR. The prevalence of CAM use at 3 and 12 months were 37.4% and 41.5%, respectively. The most frequent used CAM treatments were: chiropractice, acupuncture, and herbal products. A large majority (78.5%) of the patients expressed agreement to the discussion of CAM use with the rheumatologist, but only 31.3% of total CAM users did so because of fear of retaliation (54.4%).

ConclusionDespite the extensive practice of CAM among patients with rheumatoid arthritis, most patients did not discuss these treatments with their physicians. Associations were found between MCA use and a lower patient’s treatment satisfaction and between physician–patient communication about CAM practice and a higher patient’s treatment satisfaction.

El uso de medicina complementaria y alternativa (MCA) en pacientes con enfermedades reumáticas es prevalente pero la comunicación con el reumatólogo suele ser deficiente, lo cual afecta a la relación médico-paciente (RMP).

ObjetivosEvaluar la asociación entre el uso de MCA y la RMP en enfermos con artritis reumatoide. Como objetivos adicionales, describir la percepción del paciente sobre la comunicación con su reumatólogo respecto al uso de MCA y el patrón de uso de las diferentes modalidades terapéuticas.

Materiales y métodosEstudio descriptivo de corte transversal. El uso de MCA y la RMP se evaluaron mediante auto aplicación de cuestionarios validados (I-CAM-Q y PDRQ-9 respectivamente).

ResultadosSe incluyeron a 246 pacientes ambulatorios de una institución de tercer nivel de atención. Se encontró asociación entre una mayor satisfacción con el tratamiento y el no usar) MCA y, entre el hecho de informar al reumatólogo sobre el uso de MCA con un mayor grado de acuerdo con el médico sobre el origen de los síntomas y mayor satisfacción con el tratamiento. Las modalidades más frecuentemente utilizadas fueron: quiropraxia, acupuntura y productos herbales. El 78.5% afirmaron estar de acuerdo con comunicar el uso de este tipo de medicación al reumatólogo, sin embargo, sólo el 31.3% lo notificó por temor a represalias (54.4%).

ConclusionesPese a la alta prevalencia de uso de MCA en nuestros pacientes, la mayoría no comunicaron al reumatólogo. Se encontró asociación entre el uso de MCA y una menor satisfacción del paciente con el tratamiento y entre la comunicación médico-paciente sobre la práctica de MCA, y una mejor satisfacción al tratamiento.

The World Health Organization defines complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) as the group of healthcare interventions, resources and products which are not part of a country’s tradition and are not fully integrated into the dominant healthcare system.1 The most popular worldwide are anthroposophical, chiropractic therapy, homeopathic, naturopathic, and osteopathic medicine.2 The term complementary means that this type of practices are used in association with allopathic or conventional medicine, whilst alternative medicine is used to replace allopathic medicine.3,4 Allopathic medicine is defined as the practice of medicine by university professionals such as physicians or healthcare practitioners recognized by the healthcare authorities around the world. This practice in based on the scientific method. The integration of CAM and allopathic medicine is called integrative medicine.5

The acceptance and use of CAM is growing worldwide, and it varies according to the geographical region and ethnicity, with a higher prevalence in the East Asian countries.6,7 In the general population the frequency of use of CAM has been reported in up to 76%.8 Chronic diseases and chronic pain syndromes are the medical conditions most frequently associated with the use of CAM.9–12 In patients with rheumatic diseases, the estimated prevalence of CAM use ranges between 60–90%,13,14 and specifically in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) it ranges between 28–86%.15 It has been known, based on past studies, that in the Mexican population the prevalence of CAM use in RA is 77%16 and increases to 83%17 when considering all rheumatic conditions. The use of CAM has been associated with low treatment compliance, potentially resulting in unfavorable outcomes18,19; this emphasizes the importance of physician–patient communication about this type of practices.

Physician–Patient communications is an important component of a much more complex clinical phenomenon which is the physician–patient relationship.20,21 The latter involves a 2-way communication and the exchange of information is intended to contribute to decision making, defining treatment goals and adjusting the expectations in accordance with the course of the particular disease.22,23 This is the most important clinical event in the practice of medicine which impacts relevant healthcare outcomes such as quality of life and patient satisfaction, patient participation in decision-making, treatment compliance and physician–patient communication. A directly proportional relationship has been identified between quality and effective physician–patient communication on the one hand, and the proportion and development of outcomes, on the other.24,25

It is common knowledge that more than 50% of the patients with RA that use CAM fail to inform their rheumatologist.26,27 Specifically in Mexico, the preferred physician–patient relationship model by rheumatic patients is a paternalistic relationship,23,28 characterized by a passive role of patients in decision-making, which in turn leads to limited physician–patient communication,28,29 including disclosure about the use of CAM. In contrast, the patient-centered care models have a more participative and effective physician–patient communication, that favor treatment compliance, care satisfaction, and lead to improved functional and emotional status of the patient.30,31

Currently there is no information about the association between the use of CAM and the physician–patient relationship in RA. Therefore, a study was conducted primarily aimed at investigating the relationship between the use of CAM and the physician–patient relationship in RA patients at a third level of care institution. A second objective was to explore the patient’s perception about speaking with the rheumatologist about the use of MAC, describing the frequency of use, and the most prevalent CAM modalities among the particular patient population.

Material and methodsDesign of the trial and target populationA descriptive, cross-sectional trial was conducted including 246 consecutive outpatients with RA in a third level institution in Mexico City. Patients with overlapping autoimmune diseases were excluded (except secondary Sjögren’s syndrome), as well as patients in palliative care, and patients with a cognitive disability preventing them for completing the questionnaires. This was a convenience and non-probabilistic sampling methodology.

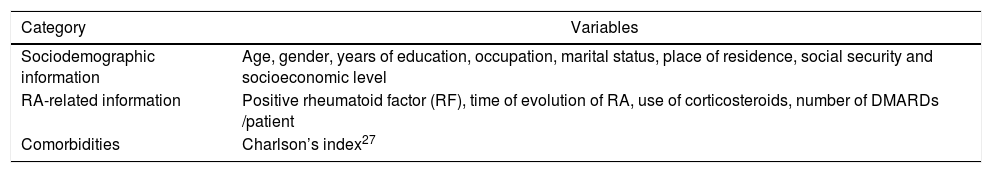

Intervention and assessment instrumentsA standardized tool was developed to collect sociodemographic information relating to RA and to other comorbidities (Table 1). The data obtained were checked against each patient’s medical record. The result of the anti-cyclic citrullinated antibodie titers was not available for the total study population, because this is an expensive test in Mexico and some patients cannot afford it.

Categories and variables of the standardized instrument for data collection.

| Category | Variables |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic information | Age, gender, years of education, occupation, marital status, place of residence, social security and socioeconomic level |

| RA-related information | Positive rheumatoid factor (RF), time of evolution of RA, use of corticosteroids, number of DMARDs /patient |

| Comorbidities | Charlson’s index27 |

DMARD: disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug.

In order to determine the frequency of use and types of CAM, the physician–patient relationship, the RA activity and the degree of treatment compliance, self-administered questionnaires were used as described hereunder. The aspects relating to rheumatologist–patient communication about the use of CAM were assessed using a standardized instrument developed by the authors.

All tools were administered by two general practitioners, previously trained and outside the Department of Immunology and Rheumatology, on the same day patients attended the rheumatology consultation. A private space was allocated within the premises of the external consultation area to complete the questionnaires. The study was conducted between March and August 2019.

The I-CAM-Q — International Questionnaire to Measure Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine,32 a tool translated and adapted into Spanish,33 is made up of 4 modules that assess: 1) consultations with professionals or experts, 2) treatments prescribed by physicians, 3) use of herbal-based medicines and dietary supplements, and 4) personal practices promoting wellbeing. In each case, the respondents were asked about the motivation and frequency of use over the past 3 and 12 months, respectively, in addition to the benefit perceived, associated with the practice of each CAM modality.

In order to assess the physician–patient relationship, the PDRQ-9 — Patient-Doctor Relationship Questionnaire was used, adapted to Spanish, using the 9-question version. It includes 9 items to quantify the willingness of the physician to help, from the patient’s perspective. Each answer suggests a Likert type scale with five categories: 1) not appropriate, 2) somewhat appropriate, 3) appropriate, 4) quite appropriate, and 5) very appropriate.34 This questionnaire does not have a specific cutoff point. Each item is rated from 1 to 5, where 5 is the best physician–patient relationship. The total score is the average of the individual scores for each item.

The activity of RA was established using RAPID 3 (Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3). This tool is easy to administer, and includes three patient-reported measures: 1) physical function, 2) pain, and 3) global assessment of the disease. The resulting scores are interpreted as follows: from 0 to 3, remission of the disease; >3–6, low activity; >6–12, moderate activity, and >12, high activity of the disease.35

The level of treatment compliance was established using the visual analogue scale (VAS) from 1 to 10, where 10 means perfect compliance. A VAS score ≥ 8 was considered the cutoff point reflecting adequate treatment compliance.

Analysis of the dataIn order to obtain information about the baseline characteristics of the population, a descriptive analysis was conducted about the principal variables of interest using frequencies and percentages for non-continuous and mean variables, with standard deviation or medians (Q25–Q75) for continuous variables with normal or non-normal distribution, respectively.

The characteristics of the patients with or without the use of CAM were contrasted against the χ2 comparative test in the case of the categorical variables, the Student-t test for continuous and normal distribution variables, and the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables with non-normal distribution. A 2 tailed p value of ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. The statistical analysis used SPSS® v21.

Ethical considerationsThe protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán (Reference IRE-2901-19-20).

ResultsSociodemographic characteristics of the study population and typical of the diseaseIn total, 246 patients were included, of which 90.2% were females, with an average age (± SD) of 53 (± 14.2) years and 10.3 (± 4.9) years of schooling; 59.3% lived in cohabitation and 92.6% had a medium-to-low socioeconomic status.

In terms of RA, the average time (±SD) of evolution of the disease was 16.6 (±10) years and 91.9% of the patients had a positive rheumatoid factor (RF). 25.5% of the patients were receiving corticosteroid therapy, and the number of DMARDs (Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs) per patient was 1.7 (±0.8) in average. Only 17.1% met remission criteria, measured by RAPID 3. Treatment compliance measured using VAS was 73.3 (±25.7) ; 50.3% were considered to adequately comply with treatment.

Use of CAM and physician–patient relationshipAny patient who answered at least one affirmative answer in any of the 4 modules of the questionnaire was considered a CAM user. “Praying for health” was not considered CAM, to avoid the bias of overestimating the prevalence. The prevalence of the use of CAM at 3 months was 37.4% (n = 92) and 41.5% (n = 102) at 12 months.

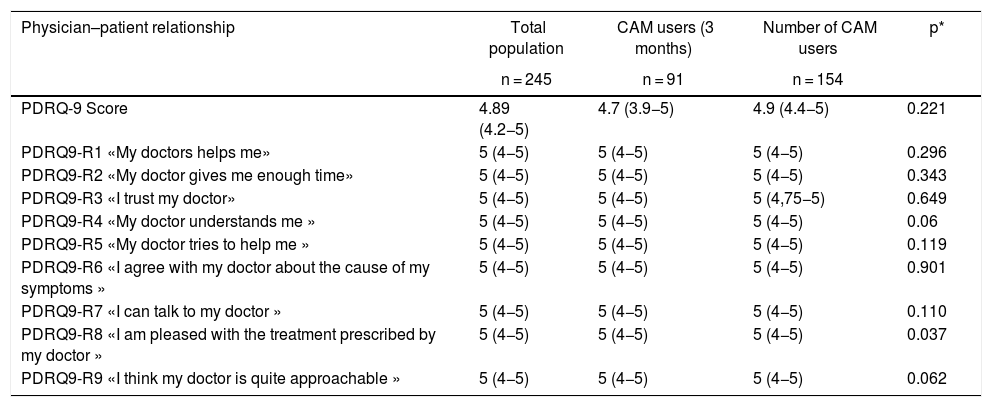

Of the 246 patients, one failed to complete the PDQR-9 questionnaire and the instrument about the physician–patient communication regarding the use of CAM. The overall PDQR-9 score and each item score individually, were higher in the group of non-CAM users, as compared with CAM users, with a statistically significant difference in terms of item 8 («I am pleased with the treatment my doctor prescribed») and a tendency in items 4 («my doctors understands me») and 9 («I think that my doctor is quite approachable»). Table 2 summarizes the global and individual scores of each item in the PDQR-9 for the total group, and the comparison between CAM users and non-users.

Physician–patient relationship assessed using PDRQ-9 in patients with RA, CAM and non-CAM users.

| Physician–patient relationship | Total population | CAM users (3 months) | Number of CAM users | p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 245 | n = 91 | n = 154 | ||

| PDRQ-9 Score | 4.89 (4.2−5) | 4.7 (3.9−5) | 4.9 (4.4−5) | 0.221 |

| PDRQ9-R1 «My doctors helps me» | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 0.296 |

| PDRQ9-R2 «My doctor gives me enough time» | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 0.343 |

| PDRQ9-R3 «I trust my doctor» | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4,75−5) | 0.649 |

| PDRQ9-R4 «My doctor understands me » | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 0.06 |

| PDRQ9-R5 «My doctor tries to help me » | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 0.119 |

| PDRQ9-R6 «I agree with my doctor about the cause of my symptoms » | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 0.901 |

| PDRQ9-R7 «I can talk to my doctor » | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 0.110 |

| PDRQ9-R8 «I am pleased with the treatment prescribed by my doctor » | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 0.037 |

| PDRQ9-R9 «I think my doctor is quite approachable » | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 0.062 |

Data presented as median (Q25-Q75).

P* asymptotic significance (bilateral) from the Mann-Whitney U test.

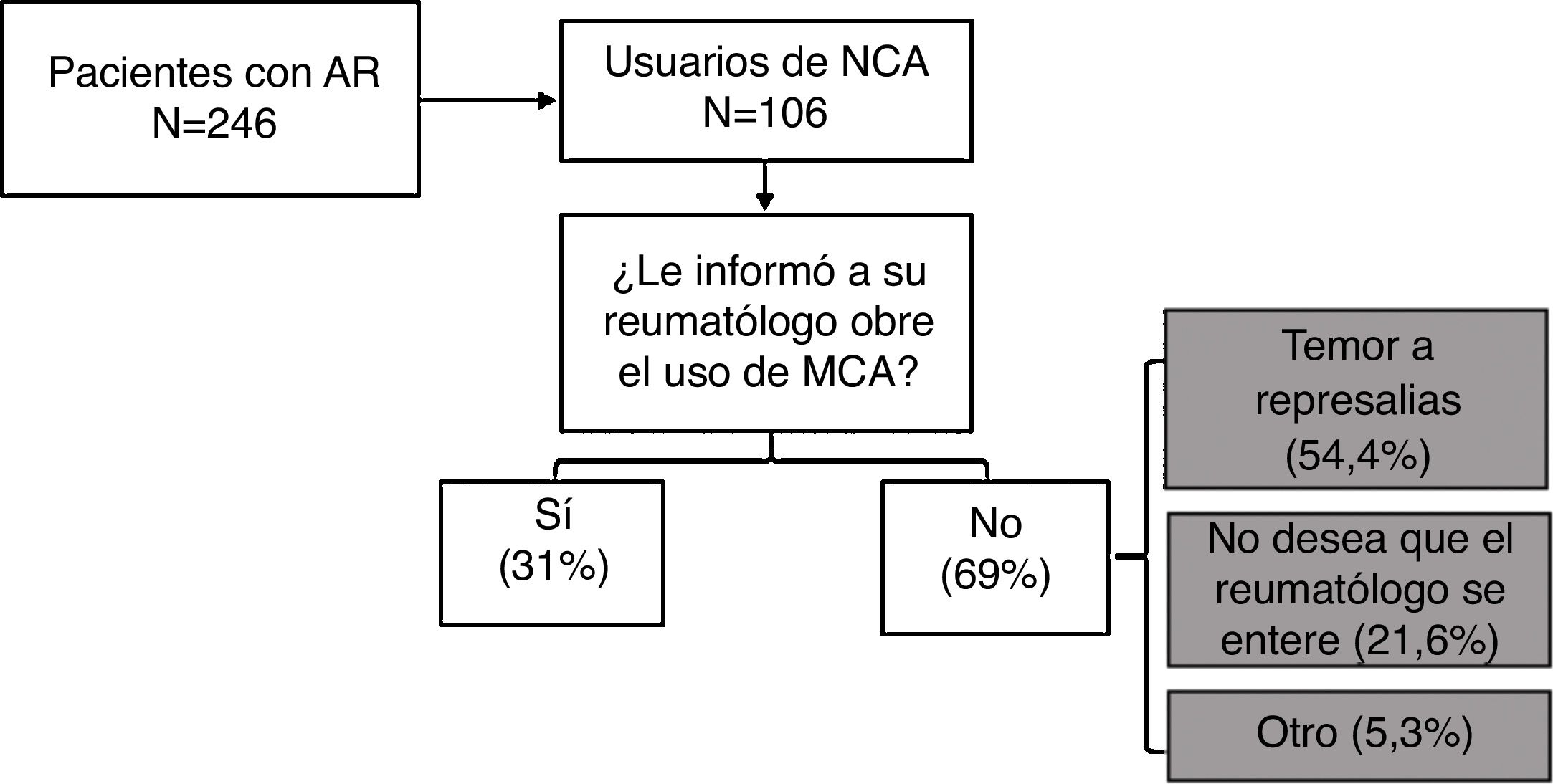

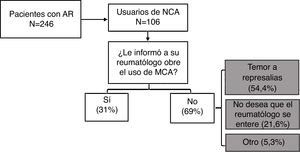

78.5% (n = 193) of the patients with RA said they agreed on telling the rheumatologist about the use of CAM. However, of the total number of CAM users, only one third said they informed their rheumatologist; the most frequent reason for not doing so was fear of reprisals (54.4%). Fig. 1 illustrates the rheumatologist–patient communication with regards to the use of CAM.

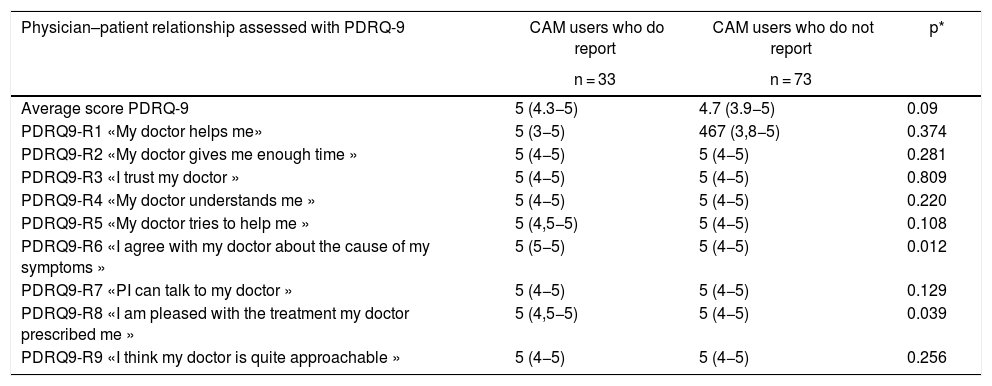

Overall, the patients that used CAM and informed the rheumatologist (n = 72) got better scores in the PDQR-9, with a statistically significant difference in items 6 («I agree with my doctor on the cause of my symptoms ») and 8 («I am pleased with the treatment prescribed by my doctor »), in contrast to those who also used CAM but failed to inform the rheumatologist. Table 3 shows the aspects relating to the rheumatologist–patient communication with regards to the use of CAM.

Physician–patient relationship and rheumatologist–patient communication about the use of CAM by patient users.

| Physician–patient relationship assessed with PDRQ-9 | CAM users who do report | CAM users who do not report | p* |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 33 | n = 73 | ||

| Average score PDRQ-9 | 5 (4.3−5) | 4.7 (3.9−5) | 0.09 |

| PDRQ9-R1 «My doctor helps me» | 5 (3−5) | 467 (3,8−5) | 0.374 |

| PDRQ9-R2 «My doctor gives me enough time » | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 0.281 |

| PDRQ9-R3 «I trust my doctor » | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 0.809 |

| PDRQ9-R4 «My doctor understands me » | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 0.220 |

| PDRQ9-R5 «My doctor tries to help me » | 5 (4,5−5) | 5 (4−5) | 0.108 |

| PDRQ9-R6 «I agree with my doctor about the cause of my symptoms » | 5 (5−5) | 5 (4−5) | 0.012 |

| PDRQ9-R7 «PI can talk to my doctor » | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 0.129 |

| PDRQ9-R8 «I am pleased with the treatment my doctor prescribed me » | 5 (4,5−5) | 5 (4−5) | 0.039 |

| PDRQ9-R9 «I think my doctor is quite approachable » | 5 (4−5) | 5 (4−5) | 0.256 |

Data presented as median (Q25-Q75).

P* asymptotic significance (bilateral) from the Mann–Whitney U test.

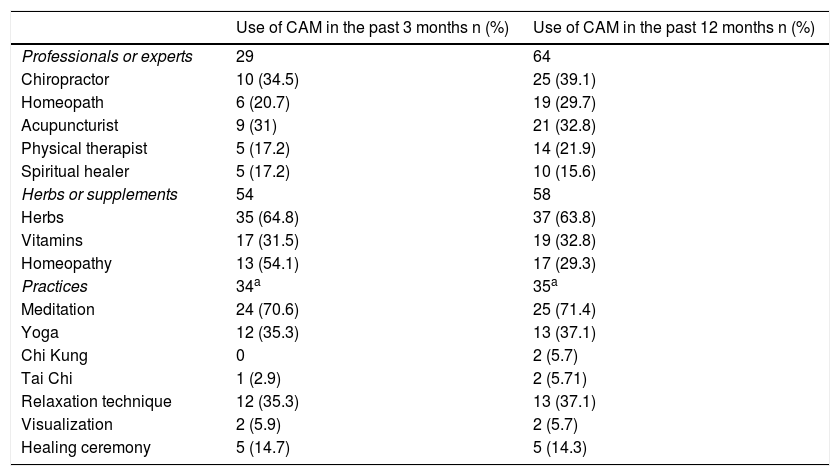

The most frequently used CAM modalities among the studied population were chiropractic therapy and acupuncture, herbal products, and meditation as a personal practice. Between 50% and 100% of the patients perceived the use of CAM somewhat beneficial, with acupuncture being the modality with lower perceived benefit, and personal practices the most beneficial. The frequency of use reported after 3 and 12 months, and the types of MAC are shown in Table 4.

CAM modalities and frequency of use at 3 and 12 months.

| Use of CAM in the past 3 months n (%) | Use of CAM in the past 12 months n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Professionals or experts | 29 | 64 |

| Chiropractor | 10 (34.5) | 25 (39.1) |

| Homeopath | 6 (20.7) | 19 (29.7) |

| Acupuncturist | 9 (31) | 21 (32.8) |

| Physical therapist | 5 (17.2) | 14 (21.9) |

| Spiritual healer | 5 (17.2) | 10 (15.6) |

| Herbs or supplements | 54 | 58 |

| Herbs | 35 (64.8) | 37 (63.8) |

| Vitamins | 17 (31.5) | 19 (32.8) |

| Homeopathy | 13 (54.1) | 17 (29.3) |

| Practices | 34a | 35a |

| Meditation | 24 (70.6) | 25 (71.4) |

| Yoga | 12 (35.3) | 13 (37.1) |

| Chi Kung | 0 | 2 (5.7) |

| Tai Chi | 1 (2.9) | 2 (5.71) |

| Relaxation technique | 12 (35.3) | 13 (37.1) |

| Visualization | 2 (5.9) | 2 (5.7) |

| Healing ceremony | 5 (14.7) | 5 (14.3) |

This study highlights that the physician–patient relationship is essential for sound medical practice and reveals a very frequent problem in healthcare, which is the lack of physician–patient communication with regards to the use of CAM. Whilst CAM use is highly prevalent among patients with rheumatic diseases, and there is limited disclosure about the issue, the information published on rheumatologist–patient communication with regards to the use of CAM and other aspects of this relationship is limited.20 Based on the available information, 50 % of the patients with RA in the United States, fail to inform the use of CAM to their treating rheumatologist.26,36

From the methodological point of view, the study has the following strengths: 1 – it included a representative sample of consecutive and non-selected outpatients with long-standing RA; 2 – with regards to the instruments used to measure the variables of interest, it should be highlighted that with regards to the use of CAM, the instrument translated and culturally adapted to Argentinian Spanish was used33; and with regards to the physician–patient relationship, the PDQR-9 tool was used, which has been validated in Spanish in the Spanish population.34 Both were administered by skilled staff, external to the Department of Immunology and Rheumatology, to minimize any information bias; 3 – A private and convenient area was used to complete the questionnaires, in order to facilitate communications. Finally, a standardized tool was developed to collect the sociodemographic and disease-related information, in order to ensure a homogenous data collection.

The sociodemographic characteristics of most of the patients assessed – of which the larger representation of females was the most salient – the average level of education, a low socioeconomic status, and poor health coverage, are the hallmark of the profile of Latin-American patients with RA,37 and hence we consider that our results may be extrapolated to similar populations.

The primary result to be underscored in this study is the association between a lower score in some items regarding the physician–patient relationship and the use of CAM. In a second clinical setting which included CAM users, we also found an association between informing the rheumatologist about CAM use, and a better score in certain items regarding the physician–patient relationship.

Whilst PDRQ-9 is an instrument to assess the quality of the physician–patient relationship as experienced by the patient, from a unidimensional perspective, the questions included relate to different aspects involved in this complex phenomenon. Such questions allow for an independent assessment of the patient’s opinion with regards to communications, the friendly approach of the physician and the treatment prescribed. The items in the PDQR-9 that showed an association were those regarding the patient’s perception of the physician’s understanding and approachability in the first clinical setting (the total number of patients with RA), the level of agreement with the physician about the source of the symptoms in the second setting (patients with RA using CAM), and the level of satisfaction with treatment in both settings.

For the first clinical setting we couldn’t find any information in the literature establishing a similar association. Consequently, the authors considered that provably the higher the satisfaction with the conventional treatment prescribed by the rheumatologist, the lesser the likelihood of the patient seeking different or additional treatment options. Moreover, the better the patient’s perception regarding understanding and approachability of the rheumatologist, the more participative and aligned with the treating physician will be the physician–patient relationship (in terms of treatment goals and preferences), resulting in a lower probability of searching for alternative treatment options.

In terms of the second clinical setting of patients using CAM and reporting (or not) its use to the rheumatologist, we suggest that the lower the patient’s perception of an agreement with the treating physician on the cause of the symptoms, in addition to poor treatment satisfaction, the more likely the failure of the patient to inform about the use of CAM. Other factors influencing the physician–patient communication about the use of CAM have been described in the literature. However, those factors were not considered in this study, or a significant association was not identified. These factors include sex, age, the number of CAM therapies used, the type of disease, and even the specialty of the treating physician.31 Hence, young patients, women, patients with comorbidities such as fibromyalgia, and those using more than one CAM therapy, tend to talk more about the use of these therapies to the rheumatologist.38,39

On the other hand, in certain medical specialties, such as family medicine, improved communication about the use of CAM has been documented in patients with arthritis and musculoskeletal pain; the percentage of patients who do inform, exceeded 70 %, which was attributed to the development of a patient-centered model of physician–patient relationship, which is characterized by increased patient participation in decision-making.31

The second relevant outcome of our study was the large proportion of patients that failed to report the use of CAM to their rheumatologist (69%) for fear of reprisals, though most of the respondents agreed in disclosing the information. Surprisingly, the overall rating of the physician–patient relationship as assessed with PDQR-9 was very high in most cases. This fact gives rise to a big question mark about the perception of patients with regards to the meaning of an «appropriate physician–patient relationship», and indirectly underscores the social phenomena that dictate the physician–patient relationship: first, a hierarchical power structure and, secondly, a prevailing paternalistic attitude of the physician in our institutions. Another explanation to the lack of physician–patient communication regarding the use of CAM could be the failure of the rheumatologist to actively ask about it, and therefore the patient simply forgot or avoided to mention it.

The hierarchical power describes a situation in medical psychology whereby the members of a particular society accept a hierarchical, rather than an egalitarian distribution of power.40 In a clinical setting, power distancing affects physician–patient communication, the exchange of information, the level of patient satisfaction and decision-making. A low power distancing means acceptance of democratic power relationships; in other words, doctors and patients are considered to be equal.41 In contrast, a high-power distancing means that the patient accepts the hierarchical superiority of the physician and hence agrees to play a passive role and simply accept any decisions, with a less participate physician–patient relationship.36,42,43 These characteristics differ from the paternalistic physician–patient relationship.

Moreover, the paternalistic physician–patient relationship reduces the probability of reporting the use of CAM, favoring potential negative clinical outcomes, such as patient dissatisfaction with medical care, misunderstandings, or diagnostic error, and poor treatment compliance.44,45 While this study failed to characterize the physician–patient relationship model, the demographic characteristics of the population assessed (mostly females, medium-to-low education, and comorbidities), in addition to a high power distancing, suggest a trend to a paternalistic physician–patient relationship, which has been documented in Mexico, particularly in the context of the public healthcare system.29

The third outcome to be highlighted was the lower prevalence of the use of MAC in our patients with RA (37.4 % and 41.5 %, at 3 and 12 months, respectively), as compared against other international and national cohorts, in which the reported frequency of use has been of up to 90 %.46 We feel that the difference in the use of CAM in our study and the literature reports, may be due to the heterogeneity in the definition and the terms used to define CAM, to the cultural, sociopolitical, and religious diversity of the populations studied, the variability in the availability of CAM in each country (with a higher availability in eastern countries47) and the difference in the instruments used to assess CAM. For instance, the frequent use of non-validated questionnaires. Our study is the only study conducted in Mexico, using the validated I-CAM-Q tool.

Praying for health (included in the questionnaire) was not considered in the analysis of the data presented, to avoid exaggerating the prevalence of the use of CAM (totaling 82.1% and 83.7%, at 3 and 12 months, respectively). In Mexico, 95.1% of the population practices a religion,48 and therefore praying is a very popular practice. However, the analyses were repeated including praying for health, and the results were similar.

Finally, with regards to the different CAM modalities, the most frequently used were chiropractic care, acupuncture, and the use of herbal products, which is consistent with the results of other cohorts.36,49

Some of the limitations of this study include primarily its cross-sectional design which hinders the identification of causality relationships in the physician–patient relationship and the use of CAM. Moreover, not all the potential confounding variables that determine the physician–patient relationship were considered, such as sex of the treating physician. Additionally, the PDQR-9 tool does not consider other dimensions of the physician–patient relationship such as discourse, non-verbal communications or the level of patient involvement in decision- making. Neither does it take into consideration the physician’s perspective.

The resulting scores using this instrument in the study population seems to show a ceiling effect, previously reported, as a characteristic of this tool. The high proportion of patients in the top scores may limit the ability to identify those that could be beyond the upper range of the instrument and prevent an accurate representation of the deviation beyond this point. Finally, both questionnaires - I-CAM-Q and PDRQ-9 - are not validated in our country and may then impact their performance.

The use of CAM is still a clinical avenue yet to be explored, particularly in the western world. There is a need to further investigate and delve into topics such as characterization of the CAM user, patterns of use, factors relating to the physician–patient relationship and association with conventional treatment compliance. With the advent of new knowledge, it should be easier to identify the patients who use CAM and hence be able to do a timely intervention, striving for an active participation of the patient in decision-making, better treatment compliance, and assertive physician–patient communication.

ConclusionsMore than one third of the population with RA studied, reported the use of CAM. Most patients agreed to inform their rheumatologist, but only one of every three users actually did; they argued fear of reprisals to justify the lack of communication with their treating rheumatologist. However, the overall rating of the physician–patient relationship was close to the best possible score. While an association between the use of CAM and the physician–patient relationship assessed with PDRQ-9 was not established, associations with some specific items were identified, in particular the item assessing patient satisfaction with treatment. This association was also applicable to the subgroup of patients users of CAM that did inform their rheumatologist.

The lack of communication about the use of CAM in our population suggests a high-power distancing and a paternalistic physician–patient relationship. It is absolutely necessary to promote a participative rheumatology visit and actively ask about the use of these interventions, particularly with a view to identifying those that could be harmful because they may interfere with the conventional treatment prescribed (due to drug interactions) o because of contraindications.50 Finally, rheumatologists should strive to include patient-centered care models in their daily practice, intended to foster patient participation, and hence a stronger commitment with their own health status.

FinancingDra. Diana Padilla Ortiz received support from the Colombian Association of Rheumatology to develop a project associated with the use of complementary and alternative medicine in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Mexico; the other authors did not receive any external financing.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to disclose.

Please cite this article as: Padilla-Ortiz D, Contreras-Yañez I, Cáceres-Giles C, Ballinas-Sánchez A, Valverde-Hernández S, Merayo-Chalico F et al. Uso de medicina complementaria y alternativa y su asociación con la relación médico-paciente en enfermos con artritis reumatoide. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2021;28:28–37.