Ocular signs of rheumatoid arthritis are severe extra-articular manifestations, which usually require aggressive management. In this report, A case is presented here of patient with peripheral ulcerative keratitis associated with corneal melt syndrome triggered by abrupt suspension of antirheumatic medication and non-ocular surgery. They symptoms responded favourably to methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide.

Las manifestaciones oculares de la artritis reumatoide son manifestaciones graves que requieren manejo agresivo. En el presente reporte presentamos un caso de queratitis asociada a derretimiento corneal desencadenado por suspensión abrupta de su medicación reumatológica y cirugía no ocular, y que respondió de forma favorable al manejo con metilprednisolona y ciclofosfamida.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is usually considered a disease primarily affecting the joints. However, the autoimmune process is in itself multisystemic, with a broad range of manifestations beyond the synovial tissue, which are called extraarticular manifestations.1 Among this group, the ocular manifestations are particularly important, not only because of the consequences on the patient’s quality of life, but because of the implications for the natural course of the disease.2 This case report discusses a case of RA-associated ocular complications and its treatment.

Patient information65-year old mestizo patient, with a history of 20 years of RA, diagnosed according to the 1987 criteria.3 At that time, the patient presented with symmetrical polyarthritis with inflammatory pain associated with high titers of positive rheumatoid factor and who received treatment with chloroquine 150 mg/day and leflunomide 20 mg/day. With this treatment, the patient was in clinical remission, with no swollen or tender joints but with established joint deformities (caput ulnae, ulnar drift, Z-thumb, and swan neck deformity). Of relevance was the patient’s personal history of coronary disease and acute myocardial infarction 3 years earlier, leading to catheterization and placement of 3 drug-eluting stents. One year prior to the patient’s admission due to dry eye symptoms, the patient visited the ophthalmologist who identified dry eye symptoms, but with no Sjögren’s syndrome; the patient received topical management with 0.4%sodium hyaluronate, polyacrylic acid and 0.1% cyclosporine, with partial control of symptoms.

The clinic began to evolve one month before the patient’s admission to the emergency department, when the patient was required to discontinue all of his rheumatoid arthritis medications to undergo bilateral hallux valgus corrective surgery. Fifteen days after surgery, the patient developed bilateral red eye, with ocular pain and photophobia. These symptoms progressed and became disabling, with a reduction in visual acuity and purulent secretion that led the patient to consult.

Physical examinationDuring the physical examination the patient was hemodynamically stable, with no remarkable findings, except for osteomuscular pathology with ankylosis of the elbows and knees, in addition to the previously described deformities of the hands and feet, with no evidence of synovitis or pain. The ophthalmological examination reported redness of the conjunctiva and ocular pain, particularly in the left eye. The practitioner was unable to perform an eye fundus due to the severe photophobia the patient presented.

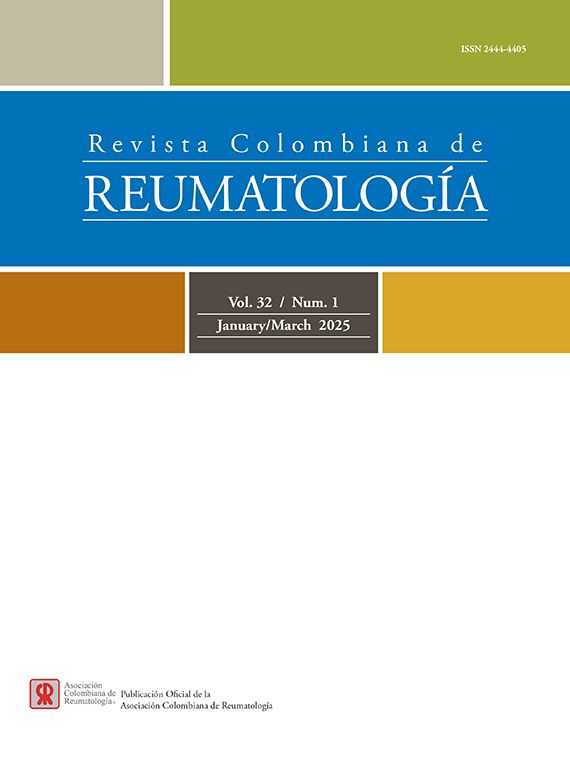

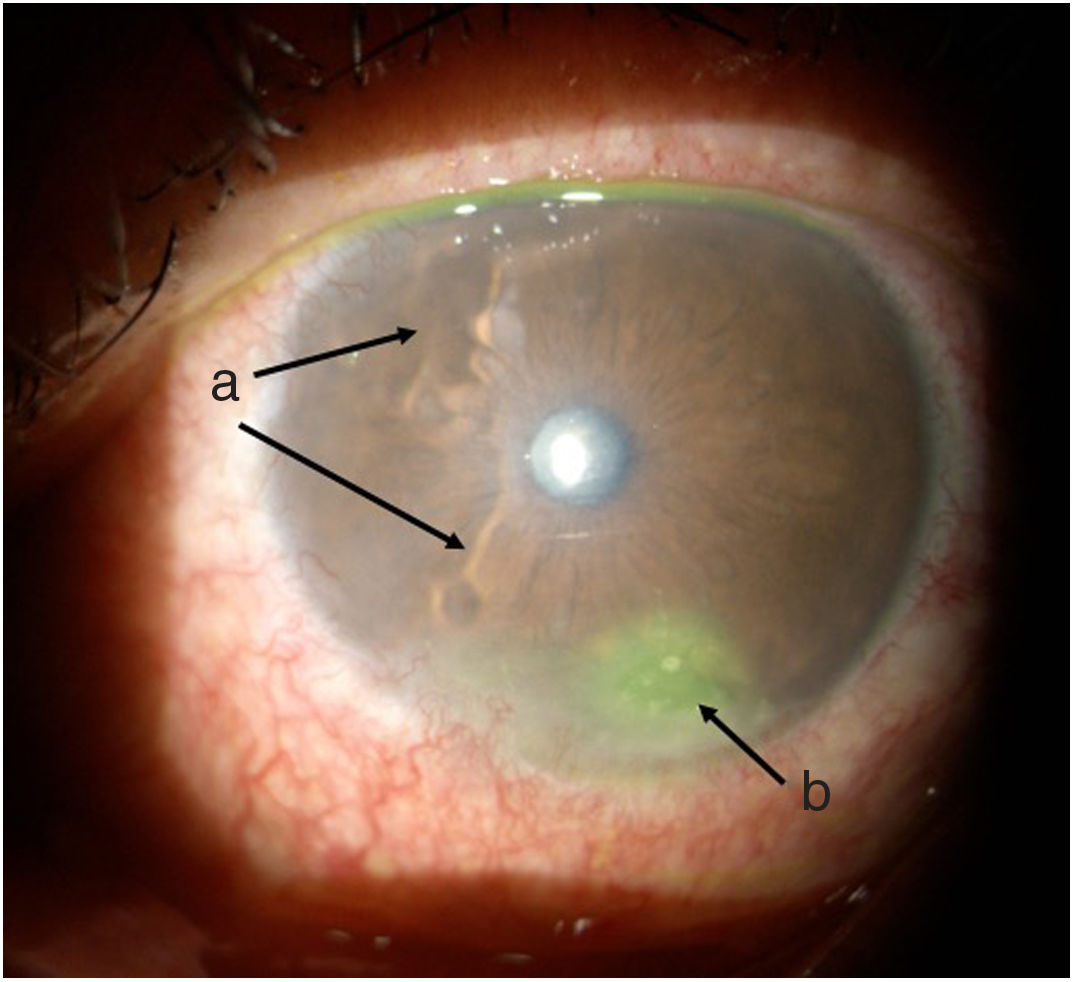

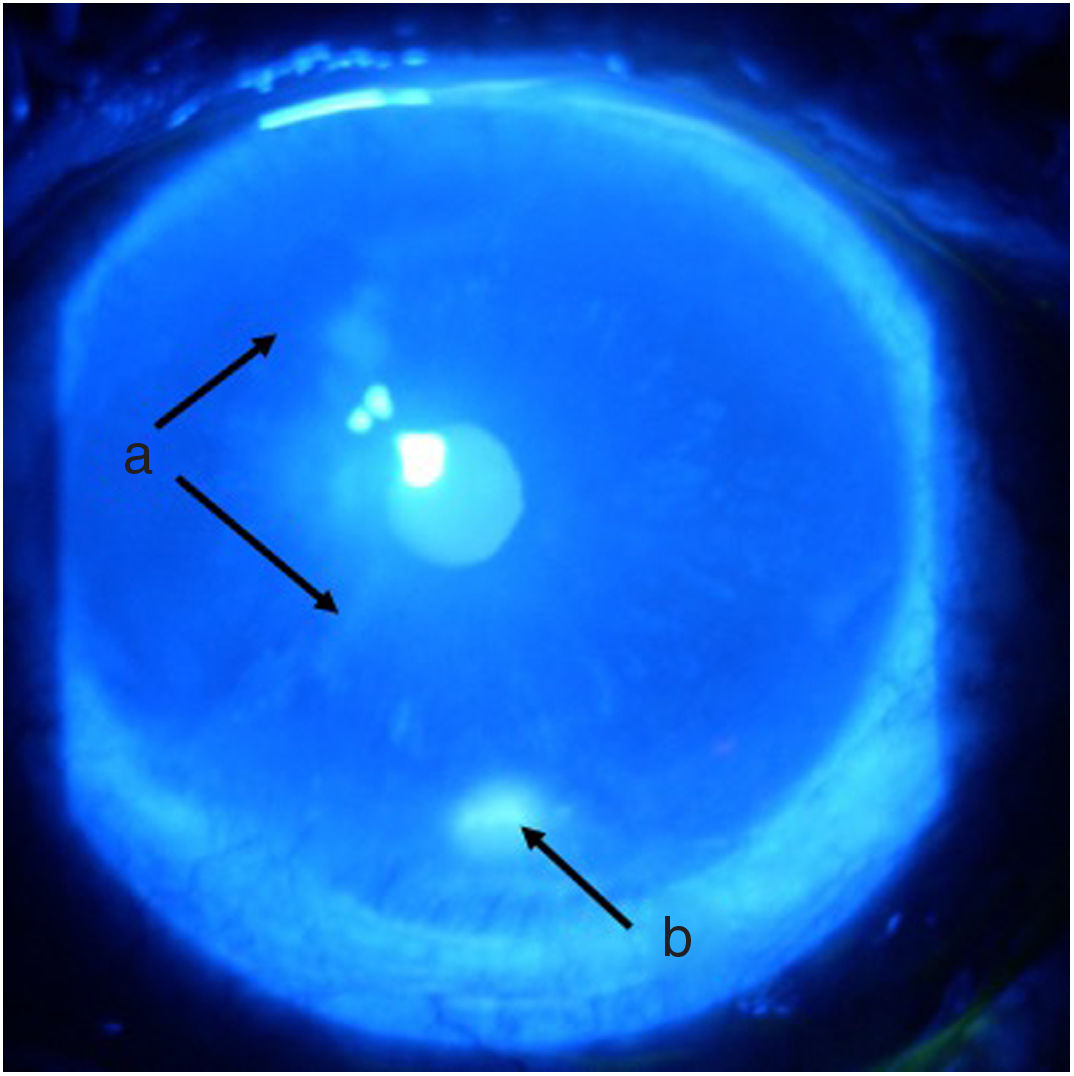

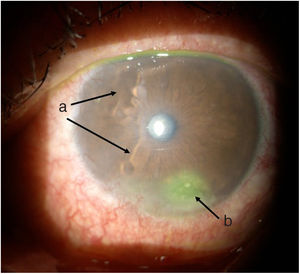

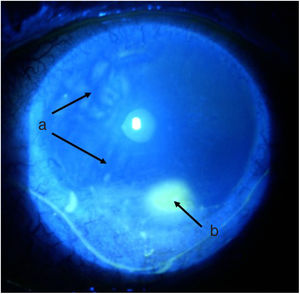

TimelineThe G.P. prescribed treatment with ophthalmic moxifloxacin, one drop every 12 h, and 30 mg of hydrocortisone every 12 h. The patient was assessed 2 h later by the rheumatology service when corneal melt was suspected, and the patient was referred for urgent consultation with ophthalmology to confirm the diagnosis and rule out any concomitant infections that could contraindicate aggressive immunosuppressive therapy. The ophthalmologist examined the patient 4 h later and found a right eye visual acuity of 20/100 (stenopeic: 20/50) and left eye: 20/80 (stenopeic: 20/50). Additionally, a slit lamp biomicroscopy with fluorescein instillation was performed, reporting mild right corneal stain dots, with no other findings in the anterior or posterior segments, compatible with moderate dry eye. The most relevant findings were in the left eye (Figs. 1 and 2), indicating moderate conjunctival hyperemia, generalized corneal stain with inferior 2 × 3 mm corneal ulcer, in addition to punched out lesions in the periphery of the cornea from 6 to 12, compatible with corneal melt.

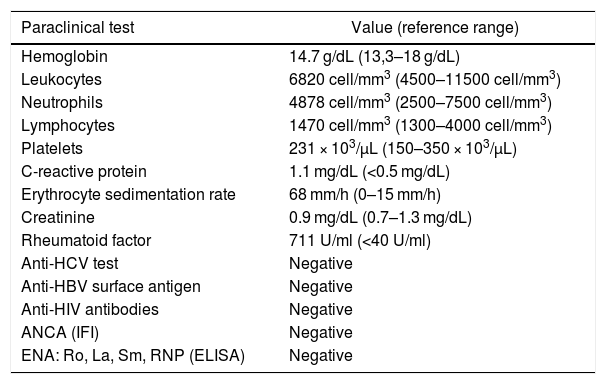

The paraclinical tests ruled out any infectious causes and confirmed the high RF positivity, with no acute phase reactants elevation (Table 1).

Relevant paraclinical tests.

| Paraclinical test | Value (reference range) |

|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | 14.7 g/dL (13,3–18 g/dL) |

| Leukocytes | 6820 cell/mm3 (4500–11500 cell/mm3) |

| Neutrophils | 4878 cell/mm3 (2500–7500 cell/mm3) |

| Lymphocytes | 1470 cell/mm3 (1300–4000 cell/mm3) |

| Platelets | 231 × 103/μL (150–350 × 103/μL) |

| C-reactive protein | 1.1 mg/dL (<0.5 mg/dL) |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 68 mm/h (0–15 mm/h) |

| Creatinine | 0.9 mg/dL (0.7–1.3 mg/dL) |

| Rheumatoid factor | 711 U/ml (<40 U/ml) |

| Anti-HCV test | Negative |

| Anti-HBV surface antigen | Negative |

| Anti-HIV antibodies | Negative |

| ANCA (IFI) | Negative |

| ENA: Ro, La, Sm, RNP (ELISA) | Negative |

ELISA: enzyme-linked immunoadsorption assay; IFI: indirect immunofluorescence.

Based on the above information and following antiparasitic therapy, immunosuppressive therapy was initiated with IV methylprednisolone 500 mg/day for three days, and single dose IV cyclophosphamide 750 mg, administered the day after the patient was admitted. The topical treatment prescribed continued unchanged, and following the administration of the methylprednisolone pulses, prednisone 50 mg/day was continued.

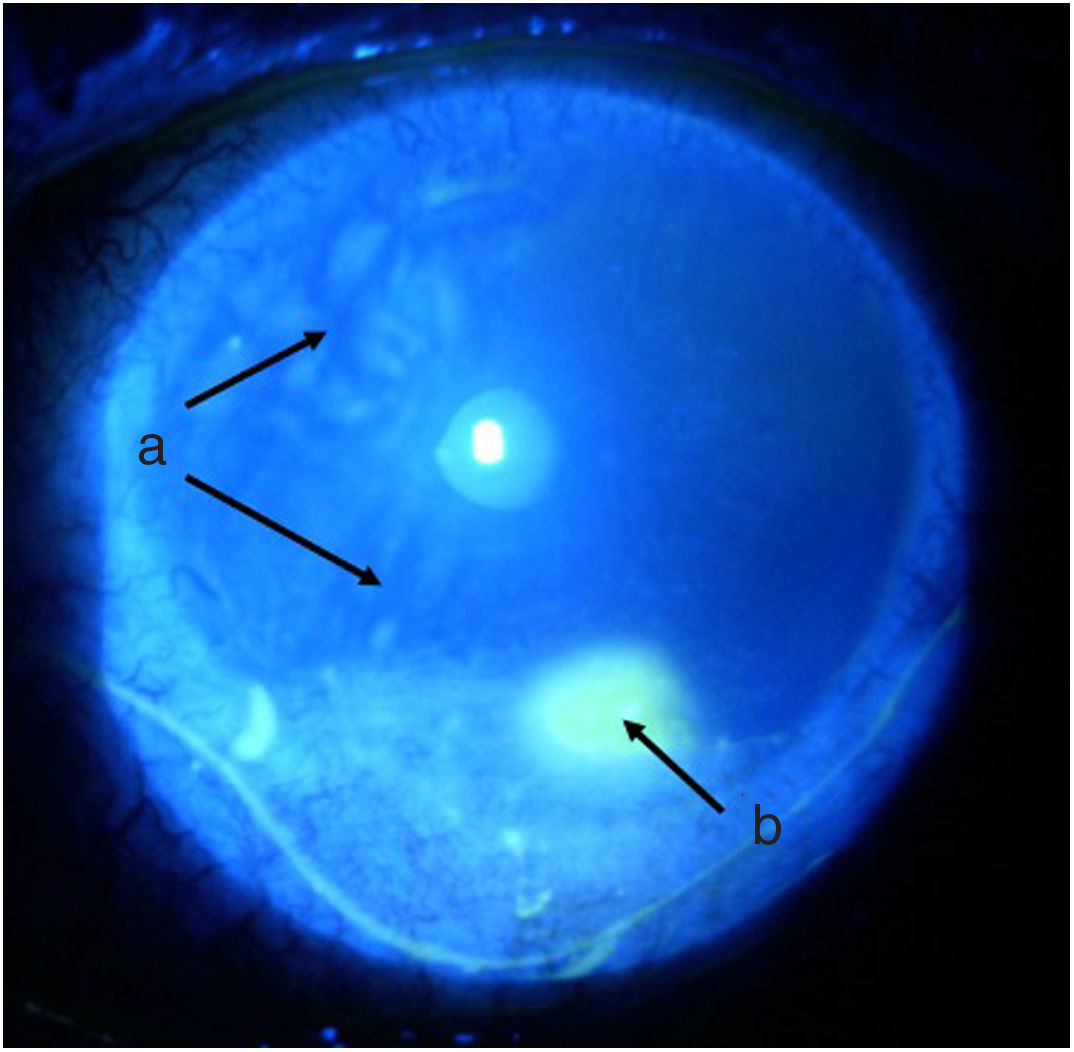

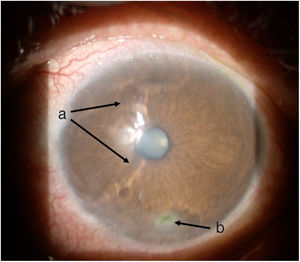

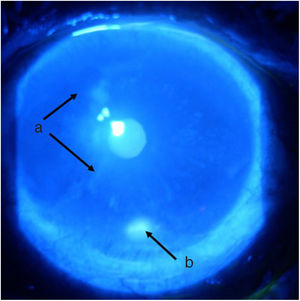

Follow-up and outcomesAfter 48 h of initiation of therapy, the patient’s symptoms improved significantly. One week later he was assessed by ophthalmology, showing a marked improvement of the ocular signs and symptoms (Figs. 3 and 4), with a reduction in the ulcer area and improved corneal surface. The patient was discharged with ongoing prednisolone therapy and a prescription for the administration of a new dose of cyclophosphamide according to a monthly regimen for six months.

This case illustrates a rare ocular complication of RA, with corneal melt. In order to understand the reasons for this complication it is important to recall the characteristics of the cornea as a complex structure, responsible for allowing the passage of light into the retina. To fulfill this purpose, the cornea must be free of any vascular structures that obstruct the passage of light, and in case of inflammation allow for the entrance of cell particles, that may result in a functional catastrophe.4 This is why humor immunity is essential and becomes an “immunological sanctuary” in the eye.5

Although the cornea looks like a homogeneous structure, the sclerocorneal limbus has some peculiarities which make it susceptible to the deposit of immune complexes: closeness to the scleral and episcleral vascular network, the presence of Langerhans cells, and the high levels of immunoglobulin M and C1, that favor the development of immune complexes and the activation of the classical complement pathway, respectively.6 This is indeed relevant when considering that a similar process is involved in the development of a number of complications such as rheumatoid vasculitis and corneal melt.7 The deposit of immune complexes activates the classical complement pathway, leading to chemotaxis of the inflammatory cells, particularly neutrophils and macrophages, which release collagenases and proteases, and cause a reduction in their respective inhibitors leading to an imbalance that destroys the corneal stroma.8,9 Moreover, the proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL1, stimulate the production of matrix metalloproteinases by the keratinocytes, which in turn accelerates the destructive process, giving rise to the development of peripheral ulcers and, in more advanced stages, to the progressive thinning of the corneal margins until perforation occurs; this is called corneal melting and the process leading to this event is called peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK). Finally, some studies have identified a significant presence of antibodies against corneal antigens (91%)10; however, these are currently considered an epiphenomenon following the initial inflammatory process and do not play a major role in its physiopathology.11

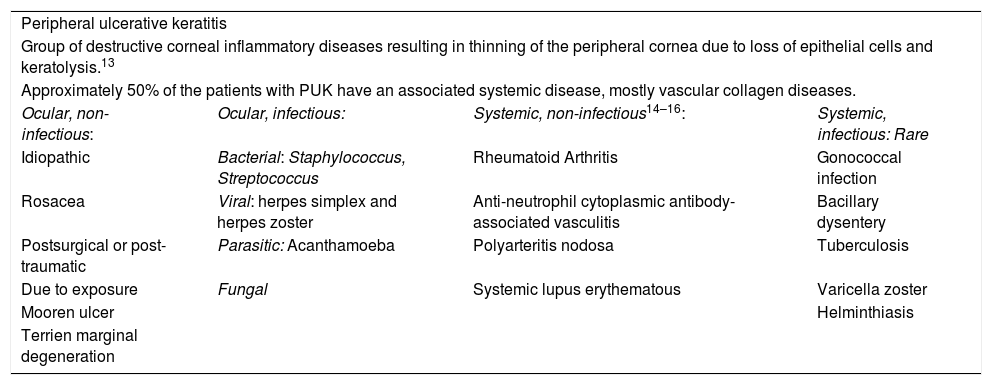

There are multiple causes for PUK that may be grossly divided into local or systemic (Table 2). The purpose of this article is to review its association with RA; nevertheless, due to the repercussions in these patients, it is always prudent to rule out any other causes, particularly infectious processes. Among the potential non-infectious systemic causes, RA is the most common pathology present in 34% of the patients, followed closely by polyangiitis with granulomatosis.12 The other diseases associated with PUK are listed in Table 2.

Causes of inflammatory corneal thinning.

| Peripheral ulcerative keratitis | |||

| Group of destructive corneal inflammatory diseases resulting in thinning of the peripheral cornea due to loss of epithelial cells and keratolysis.13 | |||

| Approximately 50% of the patients with PUK have an associated systemic disease, mostly vascular collagen diseases. | |||

| Ocular, non-infectious: | Ocular, infectious: | Systemic, non-infectious14–16: | Systemic, infectious: Rare |

| Idiopathic | Bacterial: Staphylococcus, Streptococcus | Rheumatoid Arthritis | Gonococcal infection |

| Rosacea | Viral: herpes simplex and herpes zoster | Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis | Bacillary dysentery |

| Postsurgical or post-traumatic | Parasitic: Acanthamoeba | Polyarteritis nodosa | Tuberculosis |

| Due to exposure | Fungal | Systemic lupus erythematous | Varicella zoster |

| Mooren ulcer | Helminthiasis | ||

| Terrien marginal degeneration | |||

From a different perspective, ocular involvement in RA may be frequent, representing 25% of the patients.17 Its principal manifestation is keratoconjunctivitis sicca, followed by scleritis, episcleritis, and PUK.18,19 The latter manifestation is relatively rare and has been reported in 1.4–2.5% of the patients,19,20 with an incidence of 3.01 cases per 1,000,000 inhabitants,9 though its incidence tends to decrease, probably as a result of improved treatment over the last few years.

When analyzing the characteristics of these patients with ocular complications from RA, they are usually people over 60 years old, with long standing disease and RF positive. Watanabe et al.,15 conducted a follow-up study from 2003 (the year in which biologic therapy became available), and found 8 patients with a mean age of 73 years and 12 years of disease duration. In this series, 100% of the patients were RF positive and all of them had at least with a low disease activity according to the clinimetrics11,20; this is a most significant finding, since high levels of activity are usually expected in patients with RA-associated complications. While PUK may develop spontaneously,11,20 there is usually a trigger, particularly eye surgery, since it facilitates the deposit of immune complexes and the onset of local vasculitis, together with an intensive T-lymphocyte response, in average 14 weeks after surgery.21 Similarly, although the reports are more sporadic, PUK may also be triggered by the discontinuation of immunosuppressive therapy,20 as was the case with this particular patient, who abruptly discontinued the medication due to the hallux valgus surgery.

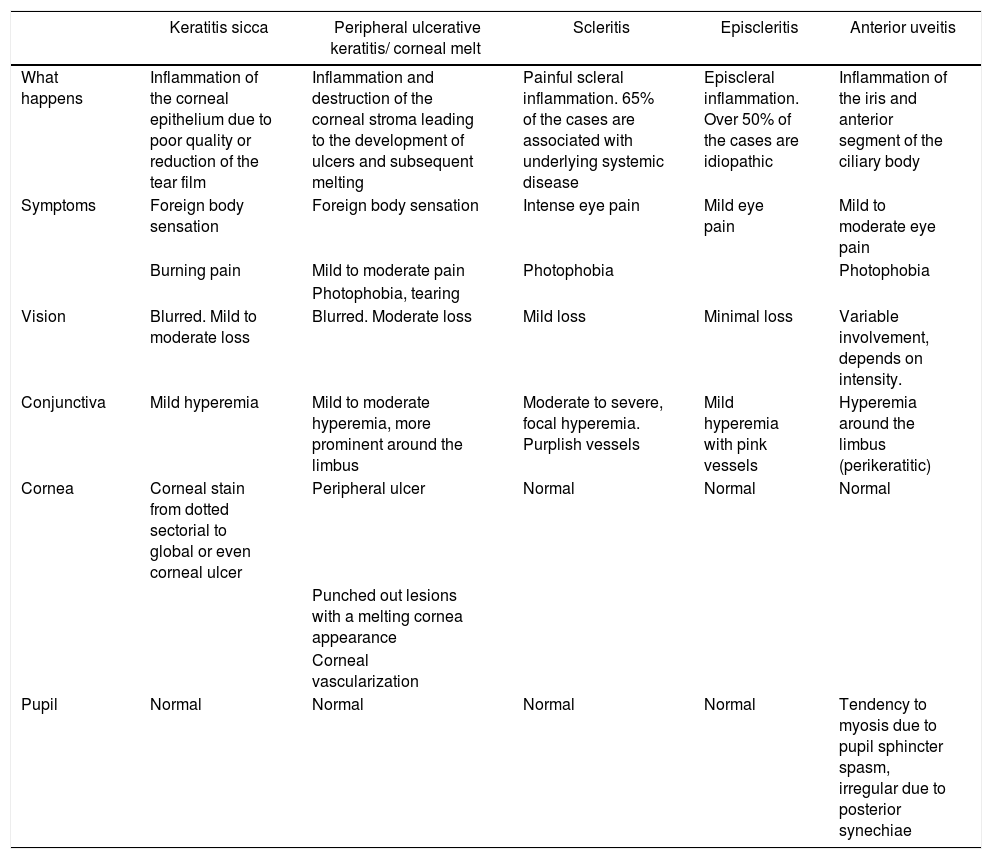

Clinically, corneal melt presents with conjunctival injection, eye pain, blepharospasm, photophobia, and decreased visual acuity. Usually a crescent shape corneal ulcer may be identified, which in some cases may be localized in the upper eye region and may be overlooked if the eyelid is not raised during the assessment.11 This inflammation presents in 70% of the cases associated with scleritis,9 which tends to distract the attention of the treating physician. Hence, any patient with RA and scleritis should be assessed to rule out PUK. From the ophthalmological perspective, it is important to define whether the ulceration is central or peripheral, since in the former case, infectious causes or dry eye-associated should be suspected15; however, central ulcerations associated with RA have a worse prognosis.22 Additionally, it is important to assess the presence of dry symptoms or Sjögren’s syndrome, since these two conditions significantly increase the probability of developing PUK.23 The explanation for this phenomenon is not totally clear, but it may be probably due to the increased osmolarity resulting from corneal dryness, which favors an inflammatory state and the activation of the metalloproteinase matrix-type 4 enzymes. Bearing in mind the range of differential diagnoses for ocular inflammation, it is necessary to make an accurate diagnosis of the specific eye involvement. Table 3 lists the different types of involvement and their major semiological differences.

Differential red eye diagnoses in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

| Keratitis sicca | Peripheral ulcerative keratitis/ corneal melt | Scleritis | Episcleritis | Anterior uveitis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What happens | Inflammation of the corneal epithelium due to poor quality or reduction of the tear film | Inflammation and destruction of the corneal stroma leading to the development of ulcers and subsequent melting | Painful scleral inflammation. 65% of the cases are associated with underlying systemic disease | Episcleral inflammation. Over 50% of the cases are idiopathic | Inflammation of the iris and anterior segment of the ciliary body |

| Symptoms | Foreign body sensation | Foreign body sensation | Intense eye pain | Mild eye pain | Mild to moderate eye pain |

| Burning pain | Mild to moderate pain | Photophobia | Photophobia | ||

| Photophobia, tearing | |||||

| Vision | Blurred. Mild to moderate loss | Blurred. Moderate loss | Mild loss | Minimal loss | Variable involvement, depends on intensity. |

| Conjunctiva | Mild hyperemia | Mild to moderate hyperemia, more prominent around the limbus | Moderate to severe, focal hyperemia. Purplish vessels | Mild hyperemia with pink vessels | Hyperemia around the limbus (perikeratitic) |

| Cornea | Corneal stain from dotted sectorial to global or even corneal ulcer | Peripheral ulcer | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Punched out lesions with a melting cornea appearance | |||||

| Corneal vascularization | |||||

| Pupil | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Tendency to myosis due to pupil sphincter spasm, irregular due to posterior synechiae |

Once the diagnosis of PUK has been made, the treatment must be aggressive and aimed at avoiding both the local and the systemic complications, since if untreated, PUK may lead to poor visual outcomes and a mortality of around 30%, usually because of the development of a subsequent rheumatoid vasculitis.20 A case series by Squirrell et al., in 1999, documented the visual and systemic results of 9 patients with RA and PUK, identifying a prevalence of patients with vision below 20/200 or no light perception; 2 patients required emergency surgery. This is why treatment must be interdisciplinary, combining the various tools available.

Two of the various options for topical management include local lubricants and cyclosporine A; the latter – at least from a theoretical perspective –, could be the preferred choice because of its impact on T-lymphocytes via the inhibition of IL-2 production.24 It should be mentioned that topical steroids shall not be used, because while they do suppress the inflammation, they also inhibit collagen production, hence delaying epithelization and predisposing to infection. Finally, surgical treatment is usually reserved for refractory cases or with imminent ocular perforation; the surgical options include cyanoacrylate glue application, which is useful in cases of imminent perforation or in perforations less than 2 mm17,25; patch graft for intermediate defects,14 and corneal transplant for large perforations, but the latter exhibits a poor prognosis.26 Here again, it should be highlighted that the conjunctival flap should be avoided, since the vascularization of the conjunctiva may aggravate the lesion.

In addition to local management, it is necessary to complement treatment with systemic immunosuppressive therapy, which includes various drugs such as methotrexate and azathioprine,11 as well as cyclophosphamide and cyclosporine,15 which in theory is an ideal agent based on the above characteristics. Moreover, biologic therapy has also been used in these cases, and the best studied agents are the tumor necrosis factor blockers27–30 and rituximab, which has proven its effectiveness in other severe RA manifestations, but paradoxically may trigger PUK by disrupting the antigen–antibody ratio, secondary to its effect on B cells.31

Whilst the initial purpose of therapy is to enable corneal scarring, it should be kept in mind that these patients are highly likely to develop subsequent rheumatoid vasculitis,32 so it is not just the patient’s vision that is at stake, and the use of immunosuppressors is the only intervention that will impact mortality,33 as shown by the studies comparing historical cohorts, with a reduction in both mortality (28 vs. 15%) and ocular complications such as perforation 34 vs. 3.4%, and enucleation 10 vs. 0.6%. This makes it mandatory to use immunosuppressors in RA-associated cases.

Our case is quite illustrative of several important factors: an extra-articular involvement dissociated from the articular inflammatory activity, the absence of scleritis as an associated ocular compromise, the need for an ophthalmological assessment for adequate diagnosis, and the discontinuation of therapy as a trigger of the clinical condition. Such a combination of factors requires the clinician to consider a high diagnostic suspicion, not just to preserve the vision, but also because of the association with severe complications such as rheumatoid vasculitis.

In summary, PUK is a severe extra-articular manifestation of RA experienced by patients with established disease and is unrelated with the articular activity. Usually it presents associated with scleritis and aggravates in the presence dry eye symptoms. The management of this condition should be aggressive, not only to prevent vision loss, but also to prevent severe systemic complications such as rheumatoid vasculitis, for which systemic therapy offers the best results.

Ethical considerationsThis case received the consent and approval of the Ethics Committee of the Clínica Universitaria Bolivariana.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Please cite this article as: Mesa Navas MA, Velásquez Franco CJ, Gómez Suárez IC, Montoya Ramírez JC. Derretimiento corneal como complicación de queratitis ulcerativa periférica en un paciente con artritis reumatoide. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2021;28:69–75.