Sjögren's syndrome is a systemic autoimmune disease that mainly affects the exocrine glands, particularly the salivary and the lacrimal glands, but which can also affect other organs such as the skin, and extra-glandular regions such as the heart, kidney, brain, the haematopoietic system and the lung. The case is presented of a patient with primary Sjögren's syndrome, whose first manifestation of the disease was pulmonary hypertension and a non-specific interstitial lung disease, with an absence of sicca symptoms. The patient received treatment with steroids and azathioprine, with an appropriate response. A literature review is also presented on the main pulmonary manifestations in Sjögren's syndrome.

El síndrome de Sjögren es una enfermedad autoinmune sistémica que afecta principalmente a las glándulas exocrinas, particularmente a las glándulas salivales y lagrimales, pero también puede afectar a otros órganos como la piel, y a regiones extraglandulares como el corazón, los riñones, el cerebro, el sistema hematopoyético y el pulmón. Presentamos el caso de un paciente con síndrome de Sjögren primario cuya primera manifestación de la enfermedad fue hipertensión pulmonar y enfermedad pulmonar intersticial no especificada, con ausencia de síntomas secos. El paciente recibió tratamiento con esteroides y azatioprina, con una respuesta adecuada. Además, se presenta una revisión de la literatura de las principales manifestaciones pulmonares en el síndrome de Sjögren.

A 40-year-old female patient with a history of hypothyroidism without management, previously asymptomatic, who consulted due to a clinical picture of one year of evolution, consisting in progressive dyspnea until functional class IV, associated with cough without expectoration and orthopnea. In another institution the patient was initially diagnosed with heart failure and management with losartan 50mg every 24h and metoprolol 25mg every 12h was initiated.

The physical examination on admission to our institution showed perioral cyanosis, tachycardia (HR: 108), with hypoxemia (O2 SAT 71%) without supplemental oxygen support; jugular vein engorgement at 90degrees, presence of holosystolic murmur grade III/IV in mitral area; respiratory sounds with bilateral basal rales; digital hypocratism and grade II edema in the lower limbs.

On admission, the laboratories showed normal blood count, renal function and liver function; C3: 91.9mg/dl (NV: 90–180mg/dl), NT pro BNP increased in 1594pg/ml, and high TSH in 76.9mIU/ml, with a decreased free T4: 0.34 (NV: 0.93–1.7ng/dl).

In view of these findings, management with levothyroxine 50μg/day was started, and a transthoracic echocardiogram was taken, which showed a normal left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 63%, with elevation of SPAP at 50mmHg, normal walls of the left ventricle, and walls of the right ventricle with marked dilation and thickening, as well as decreased contractility. Given these findings, a right hearth catheterization was performed, by which septal alterations were ruled out and a SPAP of 55mmHg was evidenced, with a positive pulmonary reactivity test with epoprostenol.

Due to the above findings, pulmonary function tests were performed to demonstrate their origin, obtaining a spirometry with a flow-volume loop with severe restrictive alteration (FEV 1: 1.29; FVC: 1.37, FEV 1/FVC: 94%), without response to the administration of bronchodilator, diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) severely reduced in 12%; 6min walk test with a result of 210m (33% of the predicted value, 632m) 2 METS (a minimum of 3 METS is expected to perform basic activities of daily living), and finally a V/Q scan was carried out which showed a pulmonary perfusion with multiple segmental defects with a scintigraphic pattern suggestive of chronic or recurrent pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE).

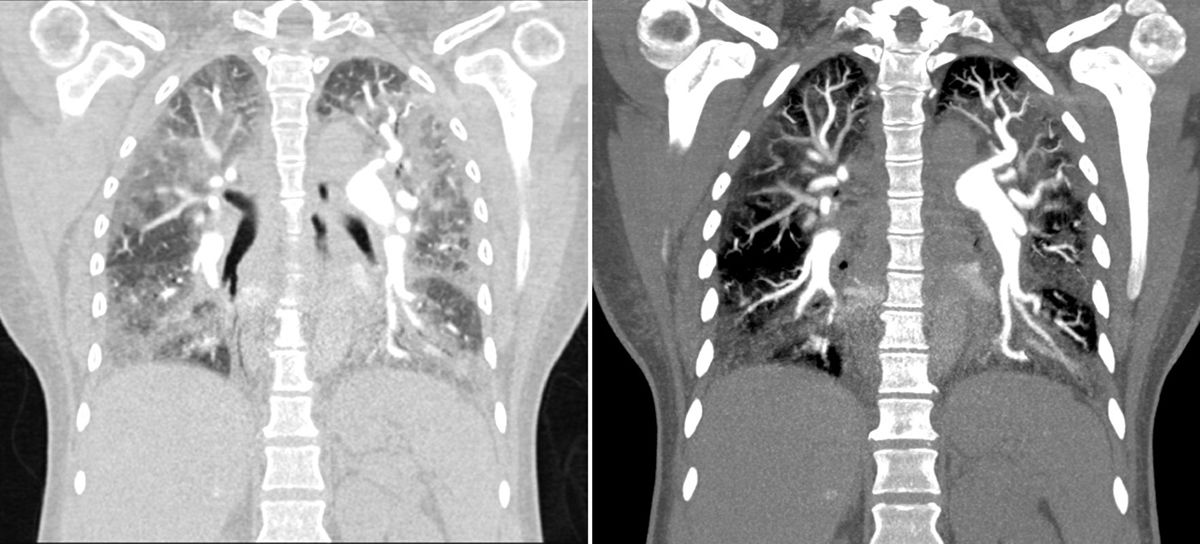

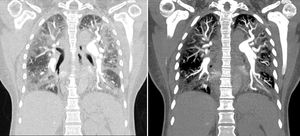

To confirm the diagnosis it was performed a chest CT angiography, which showed images compatible with thrombi in the segmental and subsegmental arteries of the lower lobes bilaterally, corresponding to chronic thrombi; there were also signs of pulmonary hypertension and cardiomegaly at the expense of right cavities, with significant alteration of the pulmonary parenchyma with a ground glass pattern (Fig. 1).

Chest CT angiography that showed images compatible with a thrombus in the segmental and subsegmental arteries of the lower lobes, bilaterally, which corresponds to chronic thrombi. There were also signs of pulmonary hypertension and cardiomegaly at the expense of the right cavities, with significant alteration of the pulmonary parenchyma with a ground glass pattern.

Management was initiated with sildenafil 25mg every 8h and anticoagulation with LMWH, as well as spironolactone, metoprolol and losartan. Given the improvement of the dyspnea, the patient was discharged 15 days after admission.

The patient re-entered 2 months later due to progressive dyspnea (NYHA functional class 2) and frequent lipothymies. The physical examination showed jugular engorgement and edema of the lower limbs; it was considered that the patient had a decompensated pulmonary hypertension and therefore was hospitalized in the ICU for vasodilator management with epoprostenol.

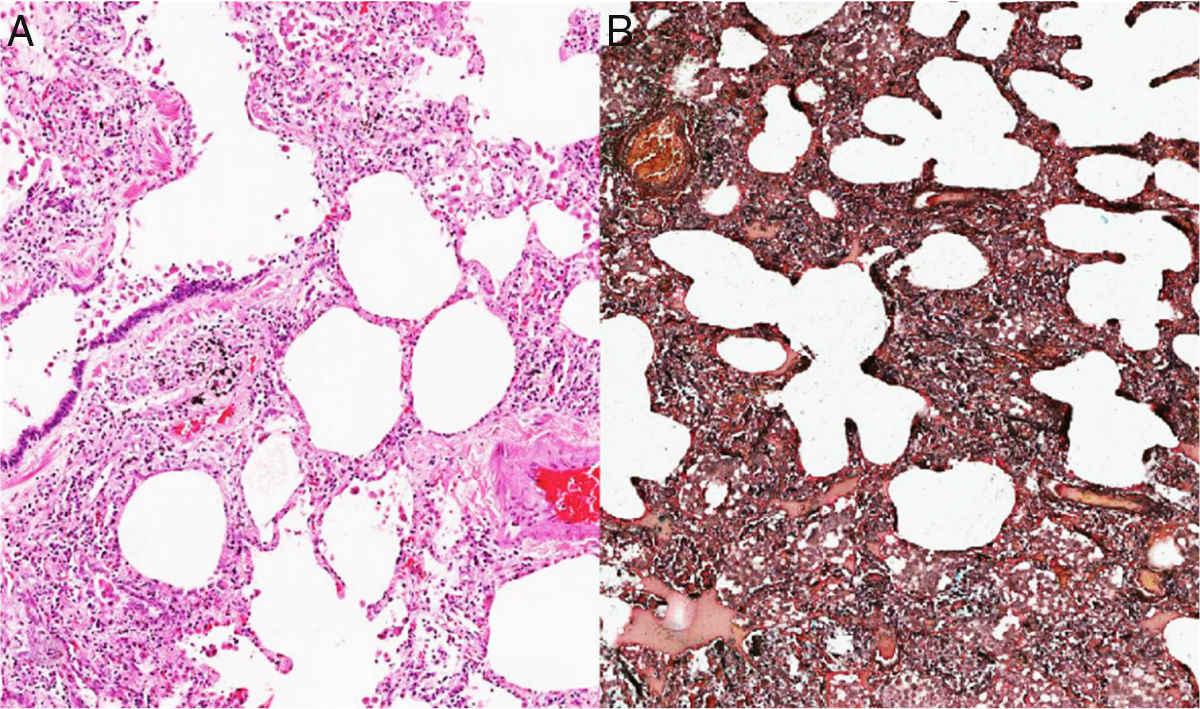

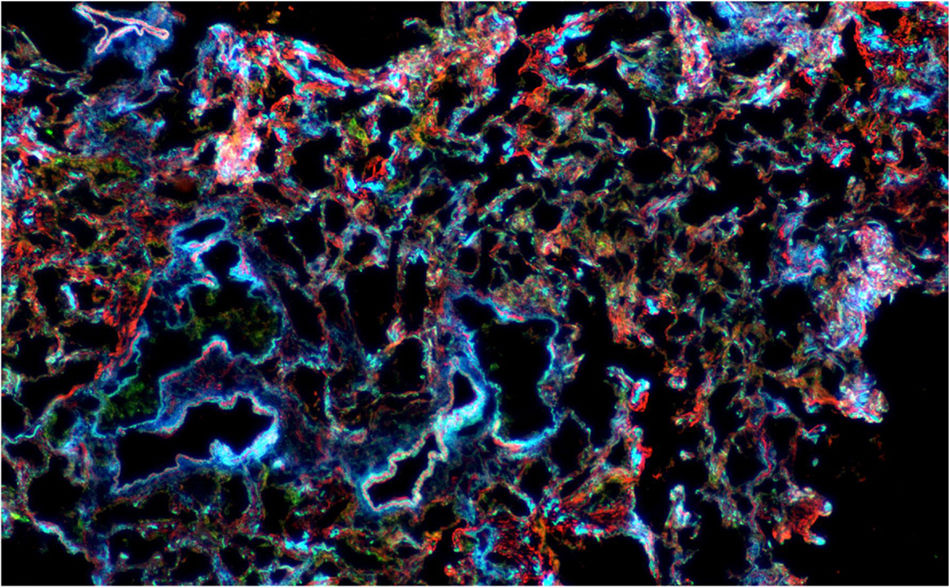

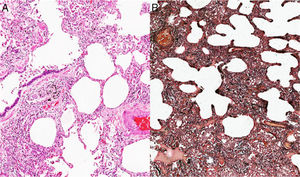

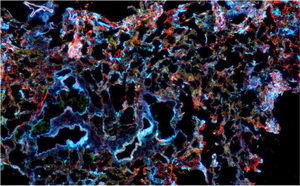

Given the complexity of the case and without a clear etiology of the process, considering that the PTE was not the only cause of the pulmonary hypertension, it was decided at a medical board to perform a lung biopsy. This pathology showed as a result the presence of a non-specific interstitial pneumonia of predominantly cellular subtype (Figs. 2 and 3), and therefore, management with prednisolone at doses of 1mg/kg/day for 10 days was started. In order to determine secondary causes, tests for autoimmune diseases were requested, which showed positivity for antinuclear antibodies with a dilution of 1:640, of fine speckled pattern. The measurement of specific autoantibodies showed AntiSSA >200U/ml (NV: <15U/ml), and AntiSSB >200 (NV <15U/ml). The rest of autoimmune profiles, including anti-Sm 2.6U/ml (NV: <15U/ml), AntiRNP 0.8U/ml (NV <15U/ml), anticardiolipin IgG 4.3GPL-U/ml (NV: <10GPL-U/ml) and anticardiolipin IgM 0.5MPL-U/ml (NV: <7MPL-U/ml) antibodies, were all negative.

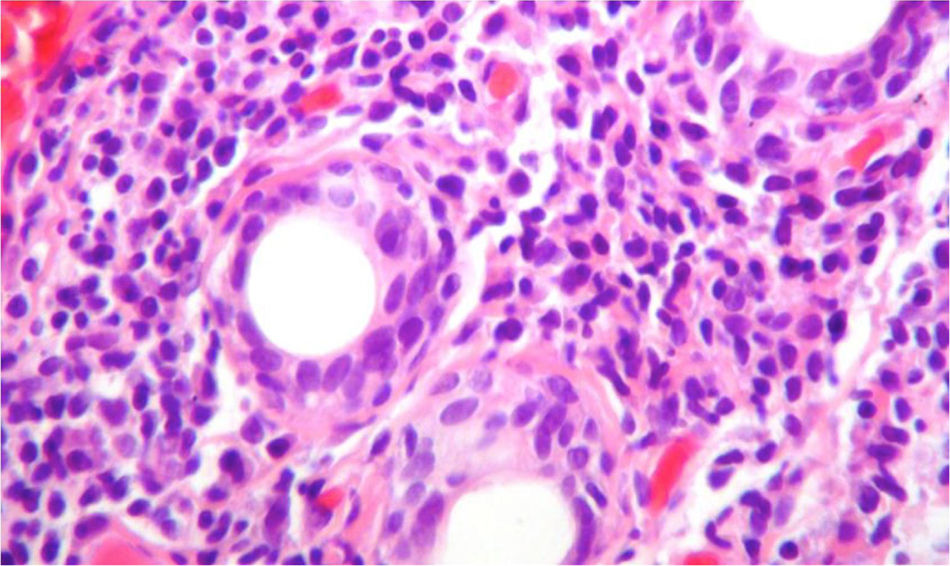

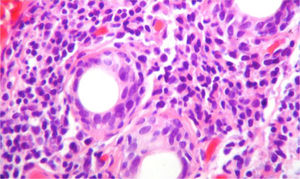

Due to the diagnostic possibilities between systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and primary Sjögren's syndrome (pSS) it was performed a salivary gland biopsy which showed a dense lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate around the ducts (more than 5 foci of 50 periductal inflammatory cells) (Fig. 4), and therefore, it was established the diagnosis of pSS. For this reason, azathioprine 50mg every day was added to the management, and the dose of corticosteroid was gradually reduced. The patient presented a significant symptomatic improvement and was discharged with anticoagulation with enoxaparin and immunosuppression scheme: prednisolone 10mg every day and azathioprine 2mg/kg/day. The evolution in the post-hospitalization period was favorable. Unfortunately, due to administrative difficulties it was not possible to make a regular follow-up in our institution in order to obtain pulmonary control testing.

Biopsy of the salivary gland with H & E stain, 40×. A dense lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate is observed around the ducts, more than 5 foci of 50 periductal inflammatory cells, which are compatible with Sjögren's syndrome (Score 4.2, scale of Chisholm and Masson modified by Daniel and Whitcher).

Sjögren's syndrome (SS) is a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of the exocrine glands, particularly the salivary and lachrymal glands, which leads to a dry syndrome due to the decrease in secretions of these glands, secondary to infiltration of inflammatory cells and neuroendocrine mechanisms.1 The disease is classified as primary, if it is not related to other autoimmune diseases, or secondary, if it arises as a complication of another autoimmune disorder, being primary in the case presented. SS can affect extraglandular organs and systems including the skin, lung, heart, kidney, and the neurological and hematopoietic systems.2

As for the pulmonary disease in SS, defined as symptomatology and alteration in structural or functional pulmonary tests, it has a prevalence that ranges between 9 and 22% of patients. However, the prevalence of the subclinical disease is higher; close to 50%.3 10% of patients with SS have lung involvement as the first manifestation of the disease, as presented by our patient, in whom the dry manifestations were not present.4

The pulmonary manifestations of the pSS include 3 groups: 1. Airway abnormalities, such as bronchiolitis (12 to 24% of patients), bronchial hyperreactivity (42 to 60% of patients) and bronchiectasis (7 to 54% of patients). 2. Interstitial lung disease, such as non-specific interstitial pneumonia (45% of patients), usual interstitial pneumonia (45% of patients), lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis (15% of patients) and organizing pneumonitis (11% of patients). 3. Miscellaneous, such as pulmonary lymphoma (2% of patients), pulmonary amyloidosis, pulmonary hypertension and PTE, which are considered rare manifestations and whose frequency is not defined within the SS.5

Pulmonary hypertension can be multifactorial, although it is classified as type 5, and its incidence as the first manifestation of the disease in patients with pSS is not known.5 The patient of the case presented pulmonary hypertension that was initially attributed to chronic PTE; later, the case could be oriented with the diagnosis of unspecified interstitial pneumonia.

Dyspnea (94%), dry cough (67%) and chest pain (22%) stand out among the most common symptoms of interstitial lung disease in SS. On physical examination, the most common findings are rales (67%), wheezing (17%) and digital hypocratism (6%); the auscultation is completely normal in 28% of patients.4

Laboratory tests do not provide a specific diagnosis, but it has been shown in some studies that patients with SS and pulmonary hypertension have more frequently positive anti-Ro/SSA, ANA and rheumatoid factor, as well as hypergammaglobulinemia.6

Diagnostic imaging plays an important role in the identification of pSS, especially CT, which allows to see the changes of the airways (bronchial wall thickening, bronchiectasis, air entrapment) and parenchymal changes (bilateral basal abnormalities with traction bronchiectasis and ground glass pattern).7

As for pulmonary function tests, spirometry shows a predominantly restrictive pattern in most cases, with a low DLCO, especially if the pulmonary involvement is predominantly at the level of the parenchyma8; this was precisely the case of our patient, in whom, due to the involvement of the lung parenchyma, the DLCO was severely reduced (12%). Conversely, if the commitment is predominantly of the airways, the pattern of spirometry can be obstructive.9

The role of bronchoalveolar lavage is not clear. A study conducted by Dalavanga et al.10 showed that 52% of patients with SS and lung disease had alveolitis, characterized by an increase in the cell count with a predominance of lymphocytes.

The treatment depends on each type of manifestation. Non-specific interstitial pneumonia can be treated with corticosteroids, azathioprine, rituximab and cyclophosphamide.5 Pulmonary hypertension receives the usual management, with calcium antagonists and pulmonary vasodilators,6 although there is little evidence of these therapies in this particular group of patients, so it is necessary to conduct studies of immunosuppressive agents to determine which is the best management for pulmonary hypertension in this specific group.

This case is quite unusual, given that the patient presented interstitial lung disease along with the presence of PTE and that it finally led to the development of pulmonary hypertension, all this secondary to SS. The relationship between PTE and interstitial lung disease is not clear and multiple hypotheses have been raised, among which the presence of a procoagulant state due to the immobility of the patient secondary to the dyspnea or to joint or muscle pain, secondary to various autoimmune diseases stands out.11 However, this is not proven, and the management of the thromboembolism in this case is the same as usual treatment.

In conclusion, pulmonary involvement in the SS is a relatively frequent manifestation. However, pulmonary hypertension as the first sign of the disease, as in this case, is an atypical expression of the SS. In addition, the case was a diagnostic challenge given that the patient had chronic PTE, and for this reason it was initially thought that this was the only cause of the pulmonary hypertension. The main conclusion from this case is that autoimmune rheumatic diseases should be suspected in all patients with pulmonary hypertension and findings of pulmonary interstitial involvement of unclear etiology.

Key messages- 1.

Pulmonary involvement in SS is frequent; however, this commitment is not usual as the first sign of the disease.

- 2.

The presence of autoimmune diseases should be suspected in patients with interstitial lung involvement whose cause is unclear.

- 3.

The clinical symptoms are nonspecific and include cough, chest pain and dyspnea.

- 4.

Images play an important role in the diagnosis, mainly the high-resolution computed tomography of the chest.

- 5.

Spirometry shows a pattern of restrictive predominance in most cases, with a low DLCO, especially if the pulmonary involvement is predominantly at the level of the parenchyma.

- 6.

Non-specific interstitial pneumonia can be treated with steroids, azathioprine, rituximab and cyclophosphamide. Pulmonary hypertension receives the usual management, with calcium antagonists and pulmonary vasodilators.

The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Posso-Osorio I, Sua LF, Tobón GJ, Fernández L. Compromiso pulmonar como manifestación inicial en síndrome de Sjögren primario. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2019;26:209–213.