Regional anesthesia techniques were recently introduced to provide analgesia for breast surgery. These techniques are rarely used as the primary anesthesia due to the complexity of breast innervation, with numerous structures that can potentially be disrupted during breast surgery.

Case reportA female patient in her sixties diagnosed with invasive ductal carcinoma on her left breast was scheduled for a simple mastectomy. After anesthetic evaluation, identification of high risk perioperative cardiovascular complications, it was proposed to perform the surgery only with regional anesthesia. A combination of pectoral nerve block (Pecs II), pecto-intercostal fascial block (PIFB) and supraclavicular nerve block ultrasound-guided were successfully performed.

ConclusionThis is the first case reporting a novel approach in a patient with severe cardiopulmonary disease who underwent breast surgery in a COVID-19 era.

Se han introducido recientemente técnicas de anestesia regional, para aportar analgesia en la cirugía de mama. Dichas técnicas son raramente utilizadas como anestesia primaria, debido a la complejidad de la inervación de la mama, con numerosas estructuras que pueden verse potencialmente alteradas durante la cirugía.

Caso clínicoPaciente femenino de unos 70 años con diagnóstico de carcinoma ductal invasivo en la mama izquierda, programada para mastectomía simple. Tras la evaluación anestésica e identificación de complicaciones cardiovasculares perioperatorias de alto riesgo, fue propuesta para cirugía con anestesia regional únicamente. Se realizó una combinación exitosa de bloqueo del nervio pectoral (Pecs II), bloqueo fascial pecto-intercostal (PIFB) y bloqueo ecoguiado del nervio supraclavicular.

ConclusiónEste es el primer caso que reporta una técnica novedosa en una paciente con enfermedad cardiopulmonar severa, a quien se practicó cirugía de mama en la era de la COVID-19.

Breast surgeries are among the most common procedures performed in hospitals. The breast is innervated mainly by intercostal nerves 2 and 6. The intercostal nerves run along the corresponding rib between the deepest layer and the internal intercostal muscle. The lateral cutaneous branch of the intercostal nerve emerges at approximately the level of the angle of the rib and provides cutaneous innervation to the lateral thorax1. The continuation of the intercostal nerve divides into the anterior cutaneous branches that provide cutaneous innervation to the medial thorax and sternum. An additional source of innervation is the supraclavicular nerve, which is a branch of the superficial cervical plexus and innervates the upper pole of the breast1.

Another important source of innervation in the chest wall is the brachial plexus. The pectoralis major muscle is innervated by the lateral pectoral nerve (C5-7), while the medial pectoral nerve (C8-T1) innervates the pectoralis minor muscle and the lower portion of the pectoralis major muscle1,2.

Most regional procedures in breast surgery involve analgesia for patients undergoing general anaesthesia, and are not performed as primary anaesthesia2,3. The techniques of choice are the thoracic paravertebral, pectoral nerve (Pecs I and II), and serratus anterior muscle plane blocks 2–4.

Case reportA 60-year-old woman (1.55 cm, 51 kg) diagnosed with invasive ductal carcinoma in the left breast, scheduled for simple mastectomy 5 months earlier after undergoing breast-sparing surgery and neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

The patient developed chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy, with congestive heart failure (NYHA class II), severely reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (∼22%), and pulmonary hypertension (mean pulmonary arterial pressure 29 mmHg). Preoperative optimisation was performed with pharmacological treatment during follow-up in the cardiology clinic. Serial tests for N-terminal pro hormone BNP (NT pro-BNP) showed a progressive downward trend (last preoperative value 963 pg/mL). As her heart disease had stabilised, and given the urgent need for cancer treatment, a multidisciplinary decision was made to propose a simple mastectomy to the patient.

The patient also presented idiopathic hypertension controlled with a combination of two anti-hypertensive drugs, dyslipidaemia, and mild obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome.

The preoperative blood panel showed mild anaemia (haemoglobin 11.6 mg/dL), with no other alterations.

After the pre-anaesthesia evaluation, we gave the patient the option of performing the procedure under regional anaesthesia, and obtained her written informed consent.

Anaesthesia preparationThe patient wore a surgical mask throughout the procedure, in accordance with our institutional protocol for patients with a negative SARS-CoV-2 test.

She was placed supine and monitoring was performed according to ASA standards, including invasive blood pressure. Supplemental oxygen was administered with a low-flow system through a nasal cannula. An intravenous line was placed and 2 mg of midazolam were administered. We decided to perform Pecs II block, pecto-intercostal fascial block (PIFB), and supraclavicular nerve branch block.

The left supraclavicular, infraclavicular and axillary regions were swabbed with povidone iodine solution. A portable ultrasound system with a broadband linear array transducer (5–12 MHz) was used.

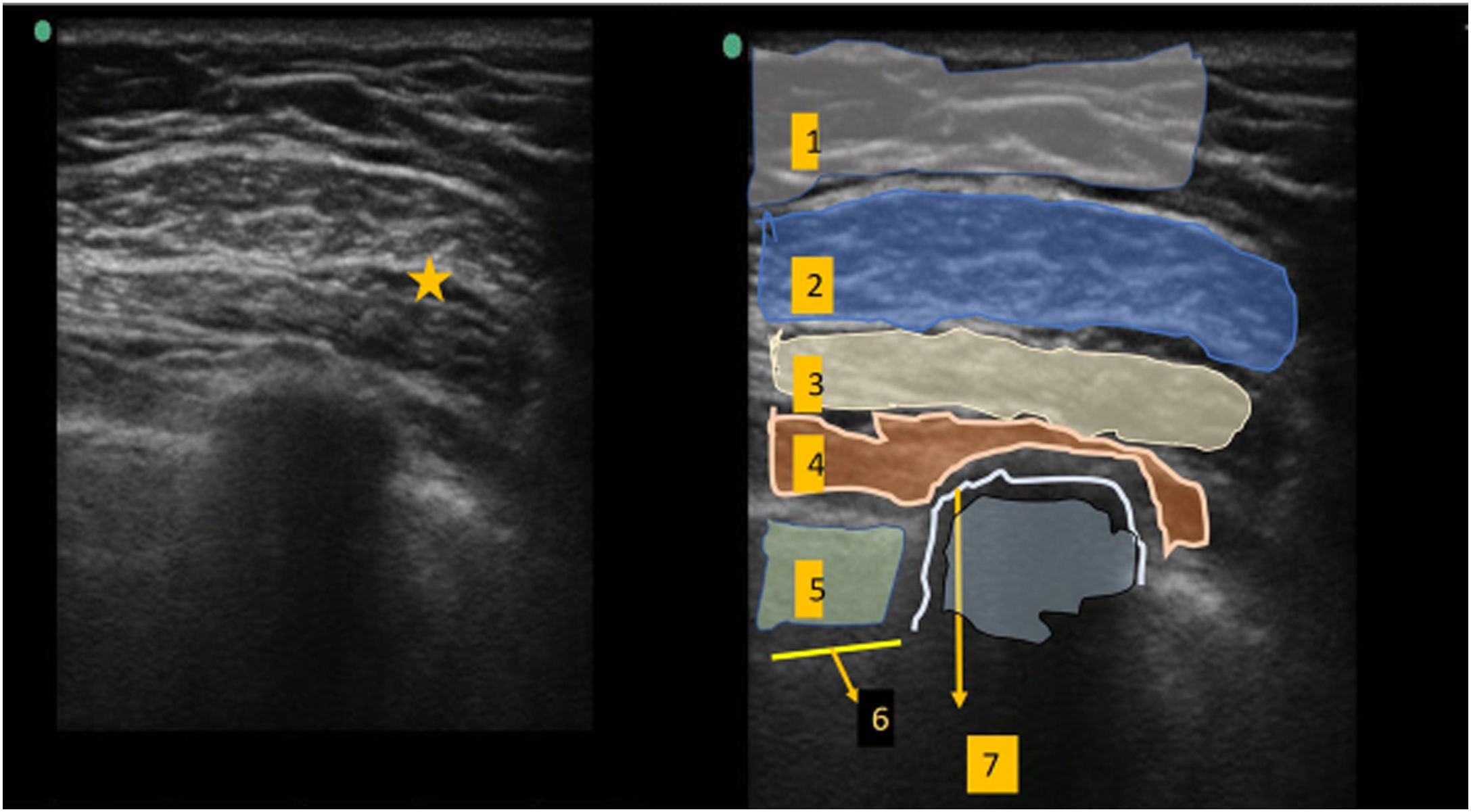

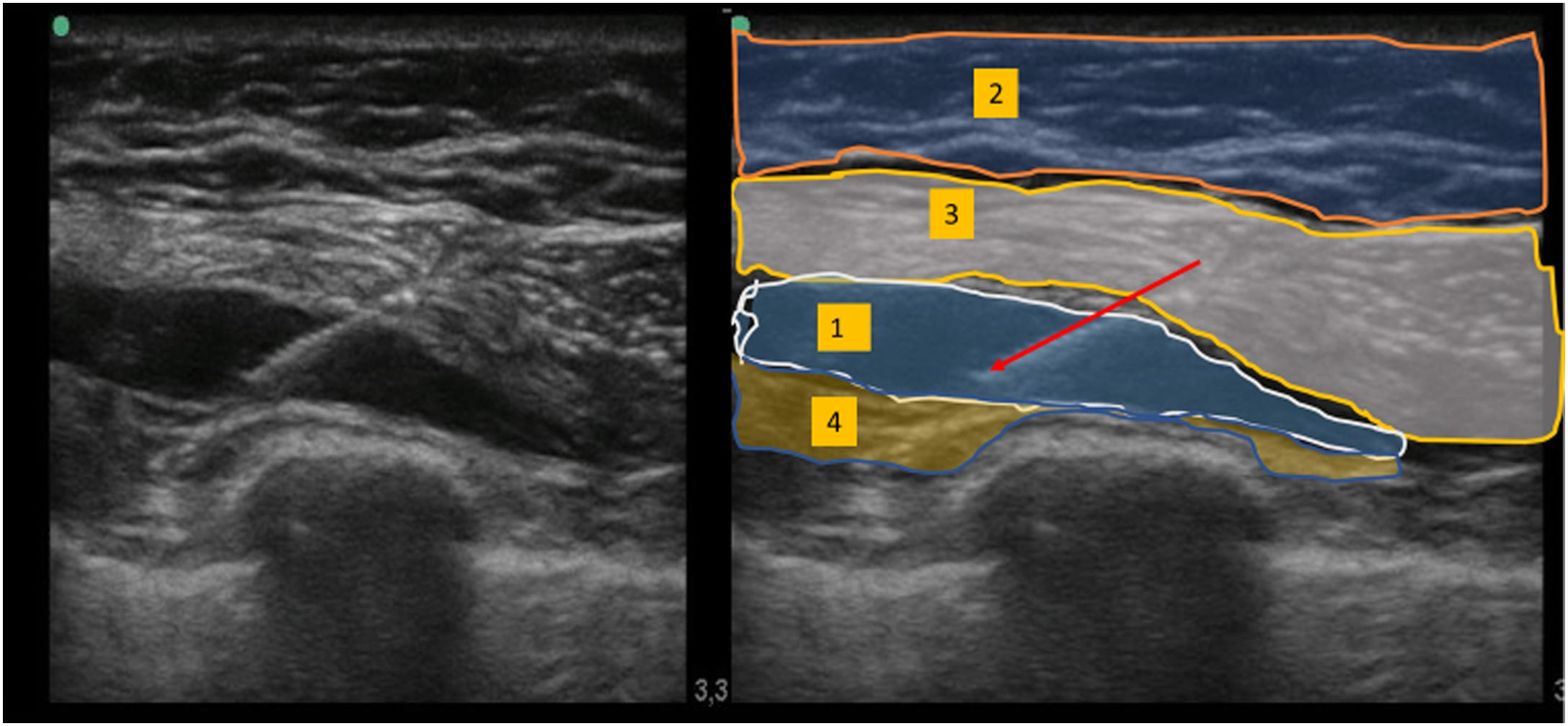

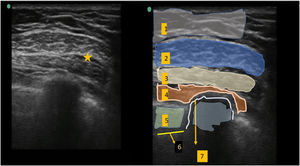

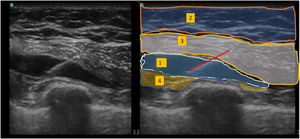

Pecs II lockThe ultrasound transducer was placed under the lateral third of the clavicle. After locating the axillary artery and vein, the transducer was moved distally towards the axilla until the pectoralis minor muscle was identified. This was used as a landmark to identify the serratus anterior muscle between the 3rd and 4th ribs. After identifying the appropriate anatomical structures, the block was performed with a 20-gauge nerve block needle using a medial-lateral in plane approach. Using saline hydrodissection, the needle was advanced to the tissue plane between the pectoralis major and pectoralis minor muscles, and 10 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine was injected (Fig. 1). Following this, 20 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine was injected between the pectoralis minor muscle and the serratus anterior muscle (Fig. 2).

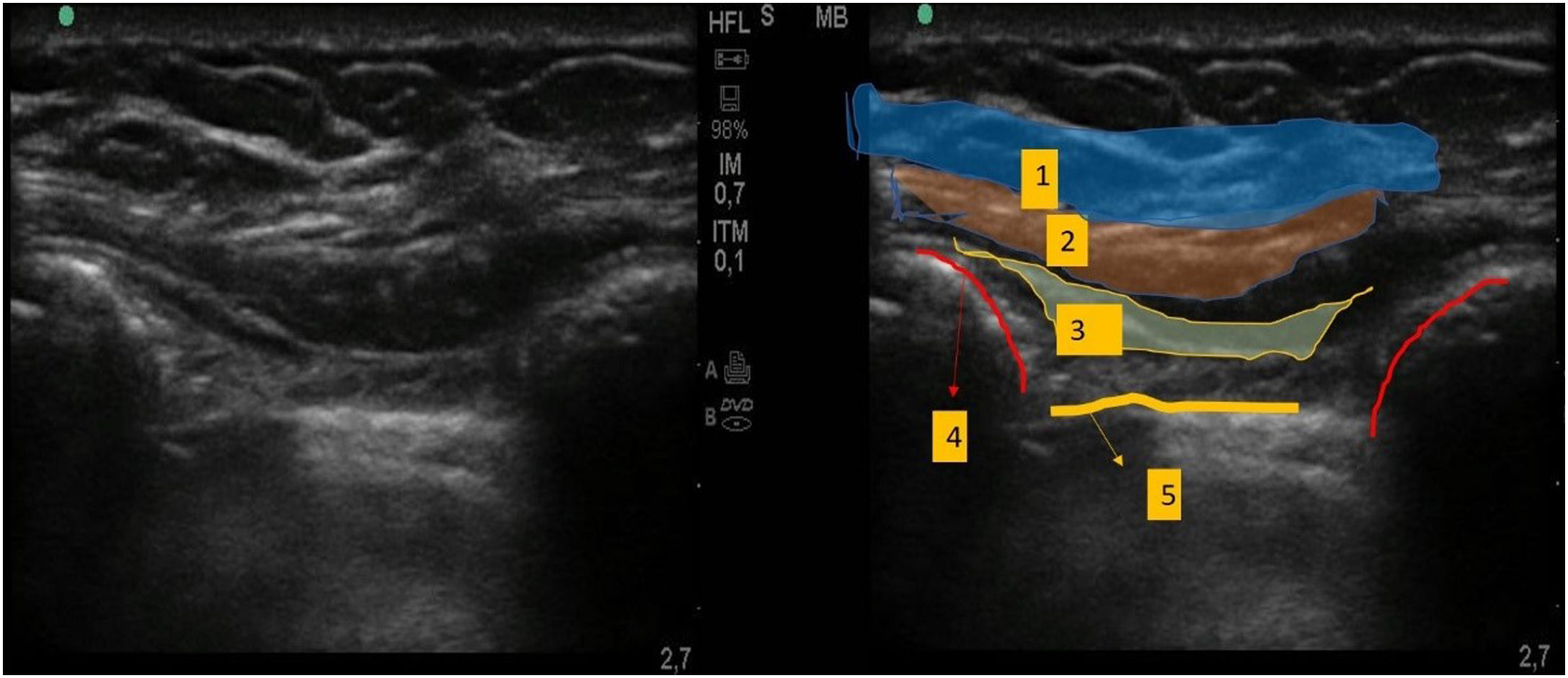

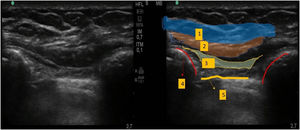

The ultrasound transducer was placed approximately 2 cm parallel to the longitudinal axis of the sternum. We first identified the ribs and pleura, and then the pectoralis major and intercostal muscles on a more superficial plane. A 20-gauge nerve block needle was advanced until the tip was situated in the fascial plane between the pectoralis major muscle and the intercostal muscles, and 10 mL of 0.25% ropivacaine was injected (Fig. 3).

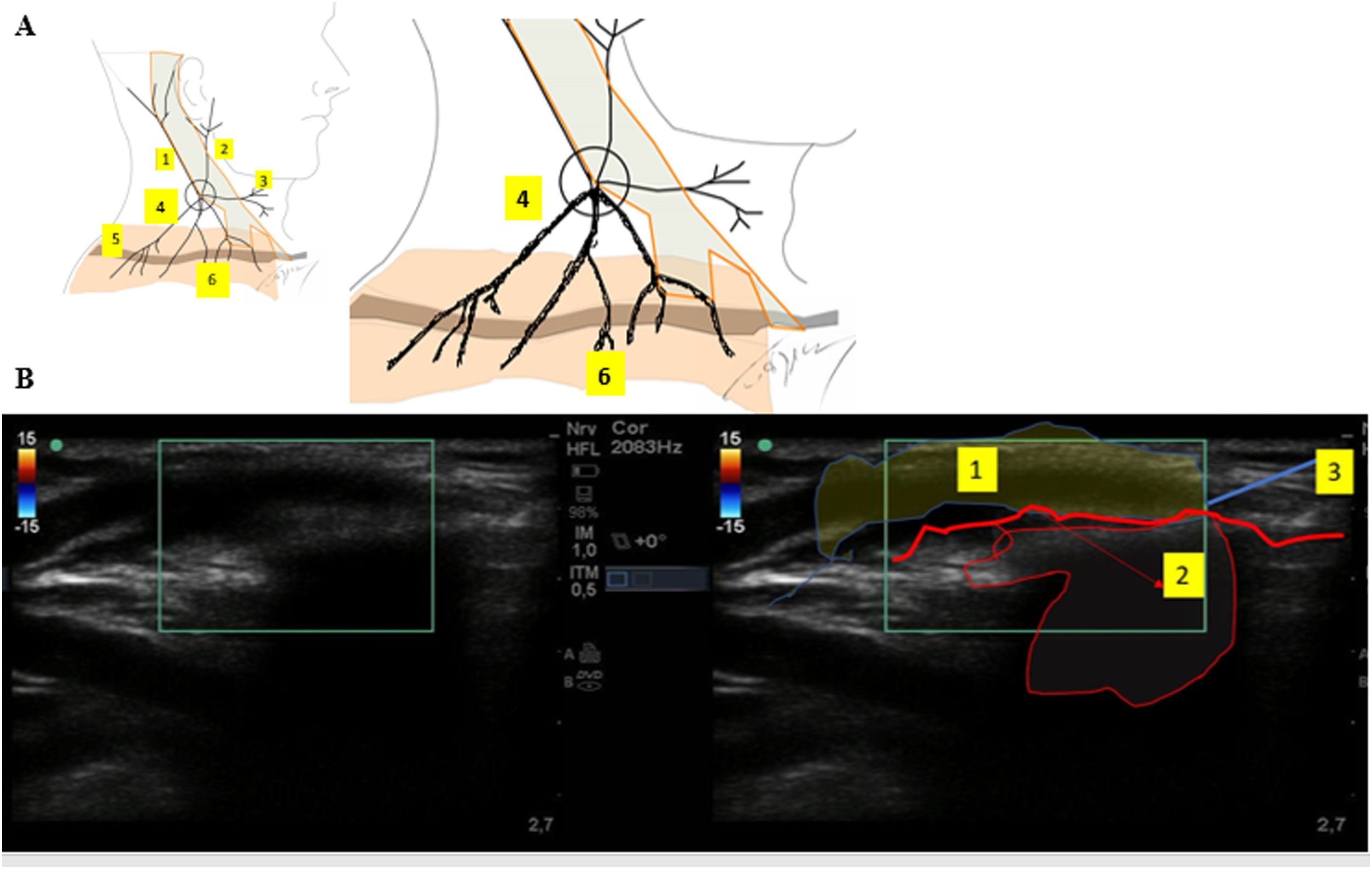

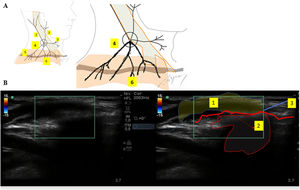

Supraclavicular nerve branch blockThe patient was placed supine with her head turned to the right, and the transducer was placed above the clavicle (Fig. 4-A). We administered a subcutaneous injection of 10 mL of 0.25% ropivacaine in order to reach the superficial branches of the supraclavicular nerve (Fig. 4-B).

A) Diagram of the superficial cervical plexus nerves.

1. Lesser occipital nerve. 2. Greater auricular nerve. 3. Transverse cervical nerve. 4. Supraclavicular nerves. 5. Clavicle. 6. Dermatome of the supraclavicular nerves. B) Ultrasound view of the supraclavicular nerve branch block.

1. Subcutaneous infiltration. 2. Acoustic shadow. 3. Clavicle.

Total time needed to achieve adequate nerve block for surgery was around 30 minutes. The ice cube test was performed to confirm anaesthesia.

During surgery, the patient reported discomfort during manipulation of the medial aspect of the chest wall (3/10 on the numerical rating scale), so the surgeon administered 10 mL of 1% lidocaine locally and 50 ug was administered intravenously. Paracetamol (1000 mg) and parecoxib (40 mg) were administered for multimodal postoperative analgesia before the end of the surgery. Total surgery time was approximately 2 h.

In the post-anaesthesia care unit, vital signs were stable, the patient presented no signs of postoperative nausea or vomiting and reported no pain (0/10 on the numerical rating scale). Admission to the intensive care unit was not required.

The patient remained haemodynamically stable throughout her hospital stay. The blood panel performed during the first 12 h post-surgical did not differ from the preoperative evaluation (NT pro-BNP 635 pg/mL). The maximum pain score recorded was 2 on the visual analogue scale, 48 h after surgery. The patient was discharged 72 h after surgery.

DiscussionRegional technique can provide high-quality analgesia by suppressing the activity of the sympathetic autonomic nervous system, which in turn reduces cardiac afterload and cardiac oxygen consumption. This was important, given the patient’s high cardiovascular risk. It also has less impact on respiratory function compared to general anaesthesia, thereby minimising the incidence of postoperative pulmonary complications. This also benefited our patient, given her pulmonary hypertension. As this case occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a particular need to reduce the number of admissions to intensive care and the hospital length of stay. Regional anaesthesia can be more beneficial in patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19, because it avoids airway management, reduces the need for aerosol-forming interventions and the potential contamination of medical staff. For all these reasons, we proposed regional anaesthesia to this patient.

Due to the complex innervation of the breast, simple mastectomy required a combination of Pecs II, PIFB and supraclavicular nerve branch blocks, making this case the first report of the concomitant use of these three blocks in surgical anaesthesia. Given the peripheral nature of these techniques, the risk of serious complications is predictably low and they are relatively easy to perform.

The Pecs II block is a fascial plane block that targets different nerve groups: the lateral cutaneous branch of the intercostal nerves, the pectoral nerves, and the long thoracic and thoracodorsal nerves1,5. Despite the risk of pneumothorax and vascular injury, no serious complications have been reported after ultrasound-guided Pecs II block5. Alternatively, multiple intercostal nerve blocks could be performed for simple mastectomy, despite the risks associated with these multi-level injections (pneumothorax)1. Additionally, nerve block does not cover chest wall innervation from the cervical and brachial plexuses. The latter could contribute to myofascial pain caused by alteration, narrowing or spasm of the pectoral muscles or fascia, even in simple mastectomy1.

Some authors have successfully used the epidural and thoracic paravertebral block (PVB), combined with brachial plexus block, local anaesthetic infiltration and/or intravenous sedation for simple mastectomy6. We decided against these more invasive techniques, given their potential for blocking the cardiac sympathetic nerve (T1 to T4), which would reduce cardiac output, cause hypotension and the need for aminergic support in a patient with compromised cardiac function6. A comparison of the thoracic PVB and Pecs II block for breast surgery showed that there were no significant differences in terms of pain scores, time to first rescue analgesia, and 24-h opioid consumption4,6. The erector spinae plane block at T5 could have been an alternative anaesthetic technique for breast surgery2. However, these regional blocks would not have provided anaesthesia for manipulation of the pectoral muscles and the infraclavicular region.

The Pecs II block alone would probably have left the sensory innervation of the medial breast intact, and therefore the PIFB block was required for the anterior branches of the intercostal nerves. This technique was recently described as an adjunct in breast surgery, and requires approximately 2-3 mL of local anaesthetic per dermatome to provide analgesia7. However, in our case, sensory blockade of the medial chest wall was insufficient, and additional local anaesthetic was required during surgery. We believe that the volume of local anaesthetic used might have been insufficient, given that only 10 mL of 0.25% ropivacaine was injected in the interfascial plane. In an earlier report of PIFB for anaesthesia in total mastectomy, the authors injected 15 mL of 0.3% ropivacaine8. Furthermore, as with all fascial plane blocks, the physical spread of the local anaesthetic, and therefore the intensity and extent of analgesia, probably varies from one individual to another. An alternative to blockade of the anterior branches of the intercostal nerves is the transversus thoracis muscle plane block technique, in which local anaesthetic is infiltrated between the internal intercostal and transverse muscles of the thorax. However, ultrasound identification of the transversus thoracis muscle can be difficult, and there is a high risk of vascular injury and pneumothorax due to the proximity of the pleura to the injection site.

The supraclavicular branches pierce the deep fascia above the clavicle, traverse this bone, and supply the skin above the upper pole of the breast9. Blockade of the supraclavicular nerve branches with subcutaneous infiltration at the clavicular level could be an effective and advantageous technique. It is easy to perform and avoids the collateral effects associated with the superficial and intermediate approach to the cervical plexus block, i.e., cervical haematoma from puncture of the external jugular vein and blockage of other nerves. The intermediate cervical plexus block, meanwhile, can cause hemi-diaphragmatic paralysis due to phrenic nerve block. This, together with relaxation of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, can have negative effects on respiratory function, particularly in patients with lung disease.

A selective ultrasound-guided block of the supraclavicular nerve in the plane between the scalenus medius and posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle has recently been described9. Although the volume of local anaesthetic is much smaller (2-3 mL), thereby reducing the risk of systemic toxicity, the complexity of its sonoanatomy led us to rule out this alternative9.

A literature search has shown that this is the first case to describe ultrasound-guided supraclavicular nerve branch block at the clavicular level. Ultrasound helped us avoid intravascular injection and to verify the injection and spread of local anaesthetic in the subcutaneous plane.

Pre- and postoperative monitoring of NT pro-BNP levels has been found to be useful in predicting perioperative cardiac events after non-cardiac surgery10. In this case, we observed a slight reduction in NT-pro-BNP after surgery, which is why we believe that the chosen anaesthetic technique could have contributed to the favourable outcome in our patient. However, no studies have yet compared postoperative levels of NT-pro-BNP after peripheral nerve block, so more research is needed.

In conclusion, various regional techniques have been introduced to provide anaesthesia in breast surgery. However, this is the first case to report the successful use of a novel approach in a patient with severe cardiopulmonary disease. The combination of ultrasound-guided Pecs II, PIFB, and supraclavicular nerve branch blocks appears to be a valid anaesthetic technique for simple mastectomy, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic when the need for intensive care must be minimised.

FundingThis article has not received any financial support.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

We would like to thank Dr Carlos Correia for his help in editing the ultrasound images and for providing us with his anatomical drawings.

Please cite this article as: Dias R, Mendes ÂB, Lages N, Machado H. Bloqueos del plano fascial ecoguiados, como única técnica anestésica para mastectomía total en la era de la COVID-19: caso clínico. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2021;68:36–41.