(1) to set a reminder of the diagnostic approach to osteoid osteomas (OOs) of the foot; (2) to define the indications of treatment for hindfoot OOs.

Material and method5 OOs were checked (3 cases located in the talus and two cases in calcaneus). The diagnosis was established by clinical and imaging data. In all cases, a calcified nidus was identified on CT, perilesional bone oedema on MRI and focal scintigraphic uptake. Two cases were treated with radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and 3 cases with surgical resections: two open surgeries and one arthroscopic surgery. Clinical and oncological outcomes were evaluated at the end of the follow-up.

ResultsNo complications were reported. The clinical outcome was excellent in all cases. One patient was initially treated with open surgery and then subsequently with RFA due to failure of the procedure. There were no recurrences after an average follow-up time of 4 years and 8 months (range, 1–12 years).

DiscussionHindfoot OOs are uncommon and their diagnosis is based on clinical data in conjunction with characteristic imaging findings. Their treatment choices depend on the location of the nidus and relationships with nearby anatomical structures.

ConclusionsThe diagnosis of an OO of the hindfoot can be ensured when the epidemiological, clinical and imaging data are compatible with this pathological entity. RFA is indicated for intracortical or cancellous cases in which the nidus is more than 1cm off the skin and significant neurovascular structures. For all other cases an open surgical resection or arthroscopic resection would be the first choice.

1) Recordar el diagnóstico de los osteomas osteoides (OO) del pie; y 2)definir las indicaciones de su tratamiento en el retropié.

Material y métodoSe han revisado un total de 5 osteomas osteoides (3 localizados en el astrágalo y 2 en el calcáneo). El diagnóstico se estableció por datos clínicos y de imagen. En todos los casos se identificó un nidus calcificado en la TC, edema óseo perilesional en la RM y captación focal gammagráfica. Se realizaron 2 termoablaciones con ondas de radiofrecuencia y 3 resecciones: 2 abiertas y una artroscópica. Se evaluaron los resultados clínicos y oncológicos al final del seguimiento.

ResultadosNo se registró ninguna complicación. El resultado clínico fue excelente en todos los casos. Un paciente fue tratado inicialmente con cirugía abierta y, después, por fracaso del procedimiento, mediante termoablación. No hubo recidivas después de un tiempo medio de seguimiento de 4 años y 6 meses (rango: 1-12 años).

DiscusiónLos OO del retropié son poco frecuentes y su diagnóstico se basa en la conjunción de datos clínicos con los característicos hallazgos de imagen. El tratamiento depende del asiento del nidus y de las relaciones de este con estructuras anatómicas próximas.

ConclusionesEl diagnóstico de un OO del retropié puede asegurarse cuando los datos epidemiológicos, clínicos y de imagen son compatibles con la enfermedad. La termoablación está indicada en casos intracorticales o esponjosos en los que el nidus dista más de 1cm de la piel y de estructuras neurovasculares mayores. En el resto de casos una resección abierta o artroscópica sería de elección.

Osteoid osteoma (OO) is a benign bone-forming bone tumour less than 2cm in diameter. It is characterised by a well-vascularised nidus of connective tissue and intertwined trabeculae of osteoid and calcified bone surrounded by osteoblasts.1,2 Its typical form is found in a patient aged 10–20 consulting with intense pain, mainly at night, in the thigh, hip and/or knee that is usually relieved with aspirin or other anti-inflammatories (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs). A nidus, calcified or otherwise, is identified on imaging tests, surrounded by trabecular oedema and periosteal reaction, usually located in the diaphysis of a long bone of the lower limbs.3,4

OOs of the foot are rare, although there are many specific publications on the subject. However most are isolated clinical cases5–15 or series with very few cases in very different sites.16–23 Their clinical presentation, on the other hand, is usually atypical due to the tumour's periarticular nature in a region such as the foot, with its complex anatomy. Therefore diagnosis and therefore treatment are often delayed more than is desirable, potentially resulting in stiffness, contractures or muscular atrophy, physeal lesions, chronic changes in bone remodelling and, finally, osteoarthritis. For similar reasons there is less of a consensus on the treatment of OOs of the foot than in other sites, where radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of the nidus, also known as thermoablation, has replaced en bloc resection as the procedure of choice.8,16,19,24–27

The aim of our paper was to record the clinical and imaging presentation of OOs of the hindfoot to facilitate prompt diagnosis and to make a proposal for the indication of the different treatment techniques available for this site.

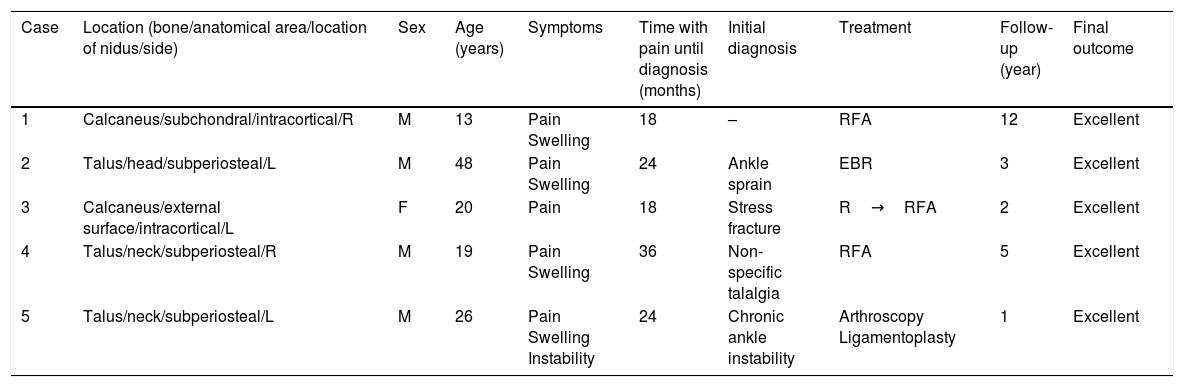

Material and methodIn the orthopaedic and trauma departments of the study authors, from 2005 to the present, 5 OOs of the foot have been treated: 3 cases in the talus and 2 in the calcaneus. Their epidemiological, clinical and imaging characteristics (plain X-ray, bone scan, CT and MRI) are detailed in Table 1, on which the diagnosis and therapeutic decision was based in all cases.

Summary of the cases of our series.

| Case | Location (bone/anatomical area/location of nidus/side) | Sex | Age (years) | Symptoms | Time with pain until diagnosis (months) | Initial diagnosis | Treatment | Follow-up (year) | Final outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Calcaneus/subchondral/intracortical/R | M | 13 | Pain Swelling | 18 | – | RFA | 12 | Excellent |

| 2 | Talus/head/subperiosteal/L | M | 48 | Pain Swelling | 24 | Ankle sprain | EBR | 3 | Excellent |

| 3 | Calcaneus/external surface/intracortical/L | F | 20 | Pain | 18 | Stress fracture | R→RFA | 2 | Excellent |

| 4 | Talus/neck/subperiosteal/R | M | 19 | Pain Swelling | 36 | Non-specific talalgia | RFA | 5 | Excellent |

| 5 | Talus/neck/subperiosteal/L | M | 26 | Pain Swelling Instability | 24 | Chronic ankle instability | Arthroscopy Ligamentoplasty | 1 | Excellent |

RFA: radiofrequency ablation; R: right; R: reaming; M: male; L: left; F: female; EBR: en bloc resection.

In cases where the nidus was more than 1cm from the skin, CT-guided radiofrequency thermal ablation was performed of the nidus (cases 1 and 4). If the nidus was less than 1cm from the skin a surgical resection was performed: en bloc when it was very accessible (case 2) or by open reaming (case 3) or arthroscopic resection (case 5) (Table 1). Case 3 was initially treated with open reaming and then, because the procedure failed, by thermoablation. In case 5 it was combined with a ligamentoplasty of the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) due to chronic ankle instability prior to the diagnosis of osteoid osteoma. In 2 cases where the nidus was resected the diagnosis was confirmed by histopathological study (cases 2 and 5).

All the patients were clinically reviewed at one, 3, 6 and 12 months after the intervention, and telephonically currently, for the purposes of the study. The complications of the surgical procedures and both the clinical and oncological outcomes were evaluated. The clinical outcomes were assessed according to the presence or otherwise of pain and its intensity (if the patient was experiencing pain), according to the mobility of the ankle compared to the healthy contralateral ankle, and function was assessed according to the activity undertaken by the patient. The oncological outcomes were assessed based on whether or not there was recurrence after follow-up. The mean follow-up time of the cases was 4 years and 8 months (range: 1–12 years).

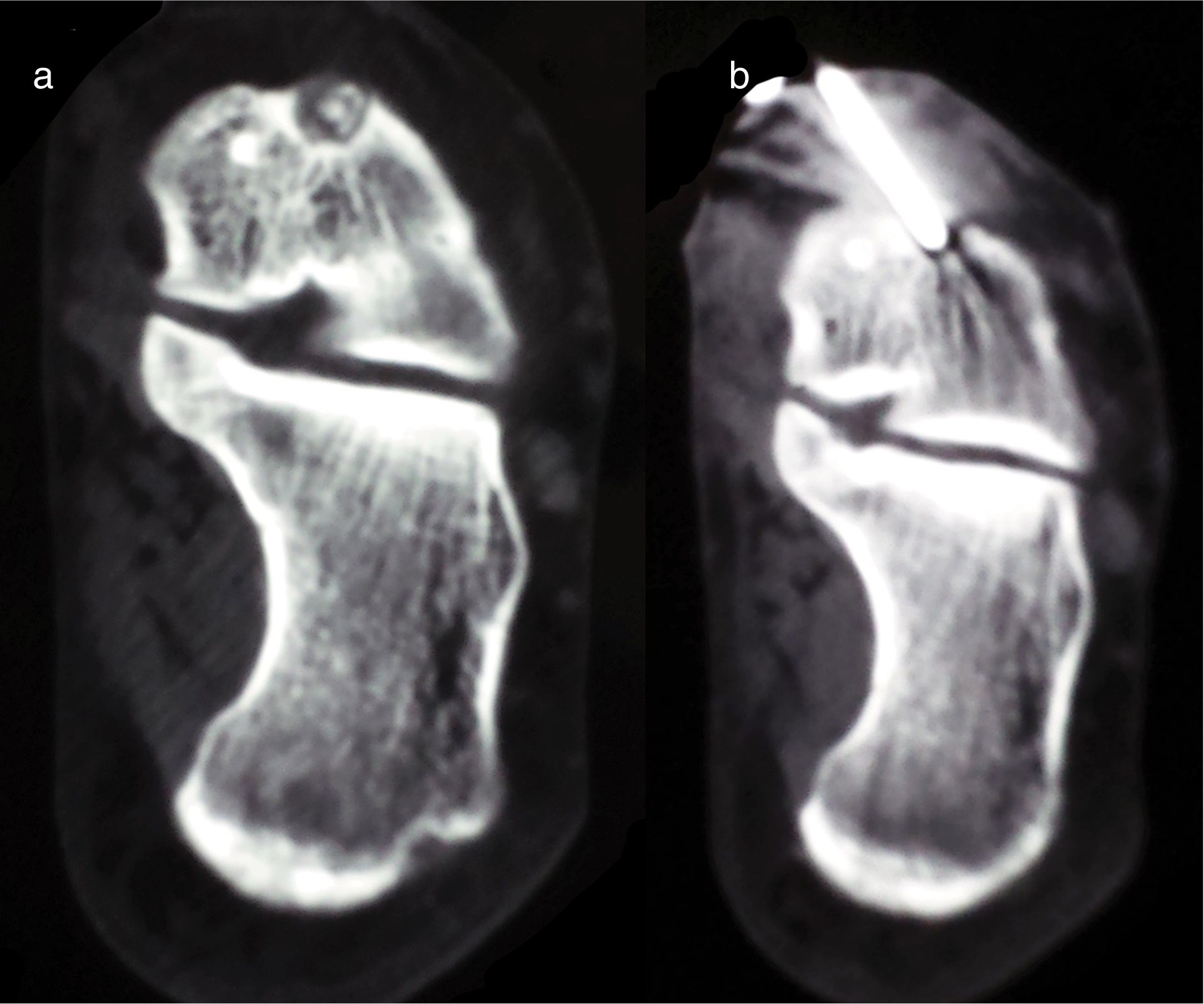

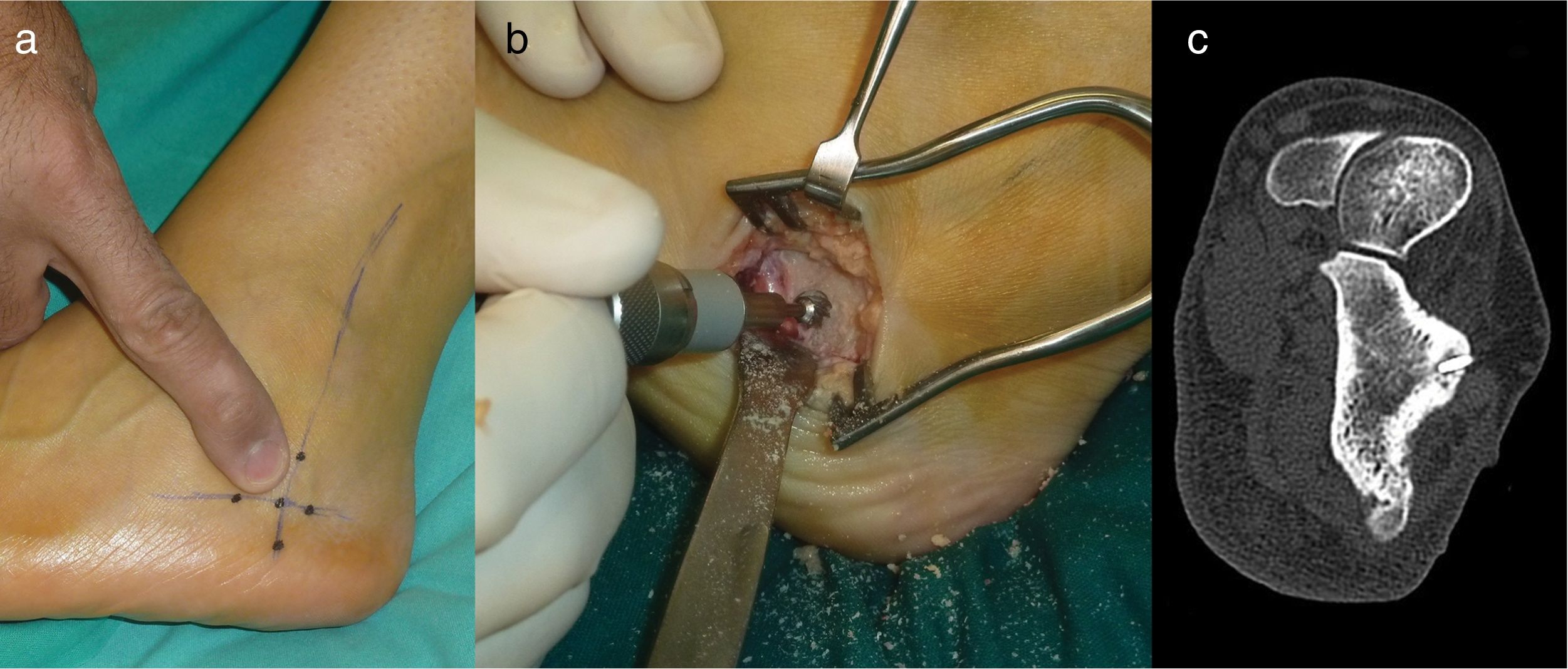

Surgical proceduresCT-guided radiofrequency ablation of the nidus (cases 1, 3 and 4)

The RFA procedure has been described in detail in previous publications by one of the authors.8,28 In all cases, the temperature of the electrode was taken to 90°C for 6minutes with a radiofrequency generator (Radionics RFG-3CF). A sample was not obtained from any of the cases for subsequent histopathological study. The patients were discharged from hospital on the day after the procedure (Fig. 1).

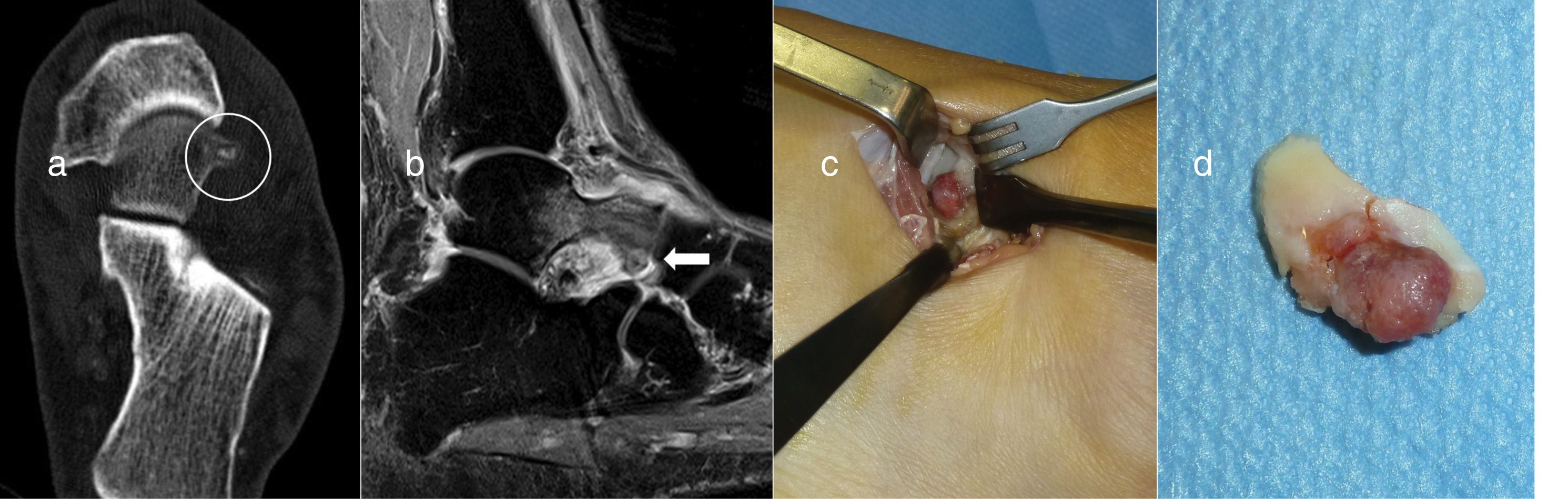

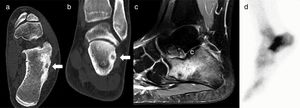

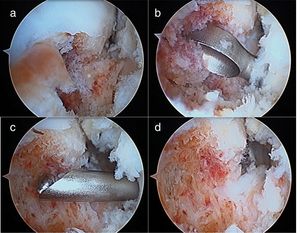

Resection en bloc (case 2)With a pneumatic tourniquet on the thigh, an anterolateral approach was used, 2cm in length in the hindfoot, on the nidus. This was easily identified as a reddish lesion protruding from the head of the talus. Once exposed it was resected en bloc with a chisel without the need for a graft or additional fixation. The patient was immobilised with a splint and kept non-weight bearing for 2 weeks, after which time activity was gradually reintroduced (Fig. 2).

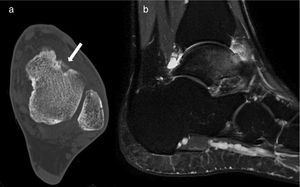

Case 2: CT of the hindfoot on an axial plane showing the calcified nidus (circle) (a). Sagittal MRI locating the nidus in the head of the talus (arrow) with bone and soft tissue oedema and adjacent synovitis (b). Surgical exposure of the nidus for en bloc resection (c). Resection specimen (d).

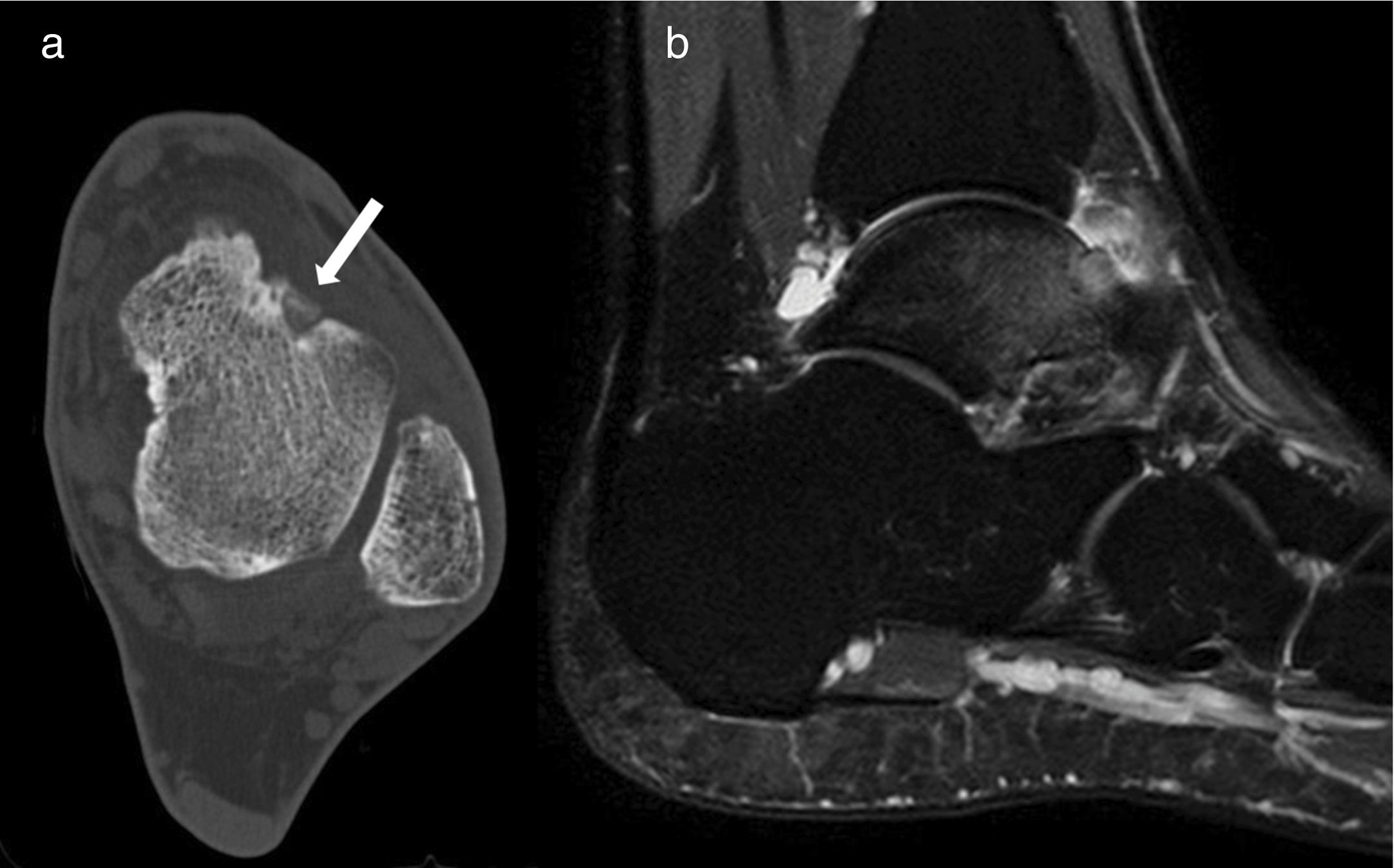

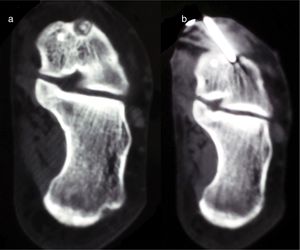

Using a pneumatic tourniquet on the thigh, the external face of the calcaneus was exposed and the supposed site of the nidus, according to the anatomical references. With a high-speed reamer the external cortex of the calcaneus was resected and we drilled down to an area of spongy bone of a redder tone that appeared to be the nidus (Fig. 3).

Case 3: axial (a) and coronal slice (b) of CT; Sagittal MRI T-2 weighted sequence (c); and bone scintigraphy (d). The CT shows the nidus with central calcification (arrows); MRI shows extensive calcaneal oedema, and on scintigraphy focal uptake of radionuclide interpreted as a stress fracture.

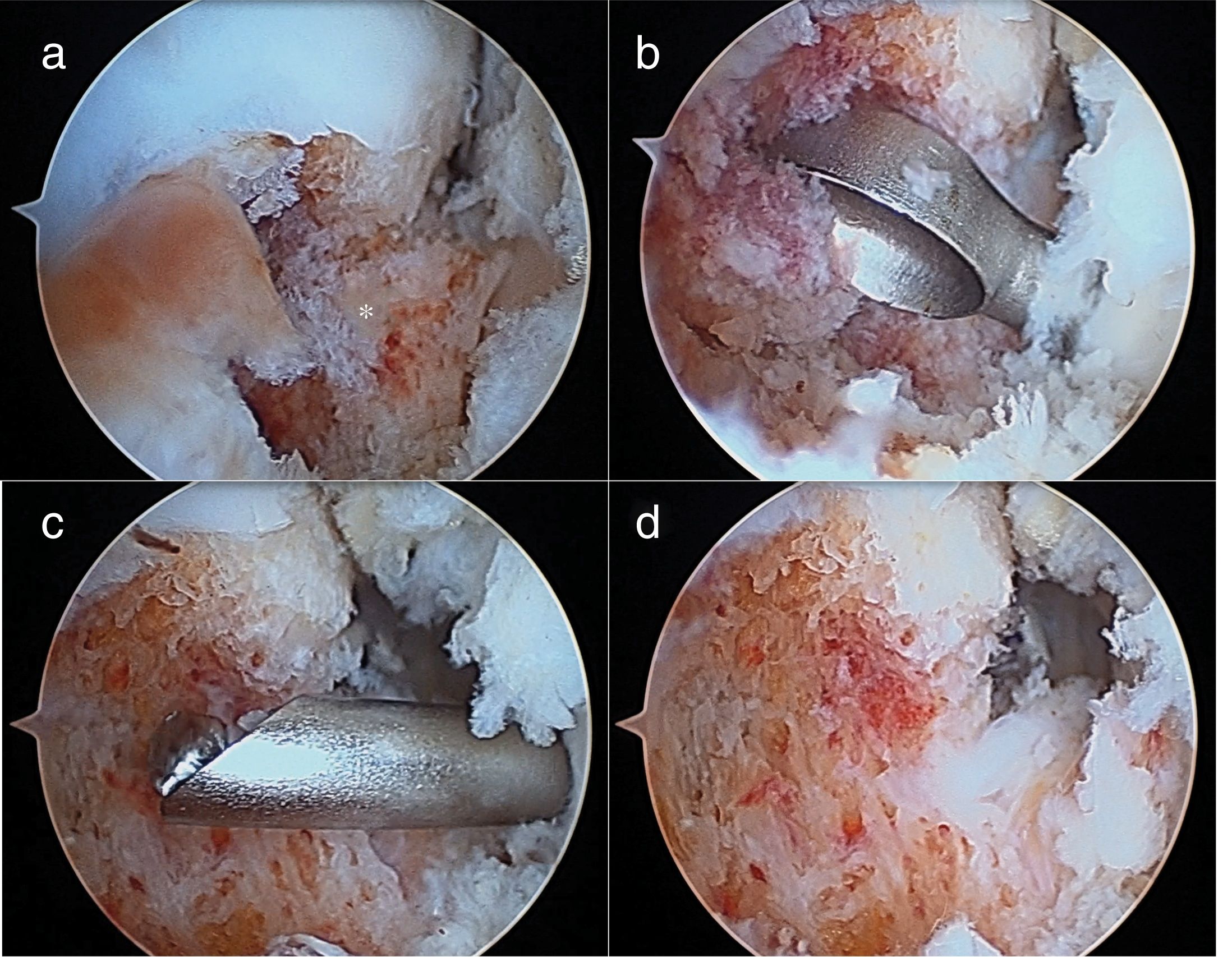

Through the traditional anterior arthroscopic ports, anteromedial and anterolateral, the neck of the talus was identified and a reddish prominence corresponding to the nidus which, using the same route, was resected with a knife and motorised reamer. Immediately afterwards an arthroscopic anatomical repair was performed of the ATFL tear by allograft. The ankle was immobilised for 4 weeks due to the ligamentoplasty. Protected weight bearing was allowed from the second week (Figs. 4 and 5).

There were no intraoperative or immediate postoperative complications. All the patients, except case 3 reported improved pain on the day following the intervention, with different discomfort to that reported previously. In case 3, due to persisting symptoms, the CT scan was repeated and it was confirmed that the wrong site had been reamed. With the patient's consent, who accepted the risk of burns to the skin due to the proximity of the nidus, a radiofrequency thermoablation was performed with no complications (Fig. 6). Three months after the intervention all the patients were rigorously asymptomatic, with complete mobility of the ankle and able to lead a normal life, which they have continued to do to the present day, with no recurrence of the tumour. A control MRI was performed at 6 months for case 2, following the thermoablation, showing complete resolution of the bone marrow and adjacent soft tissue oedema. The clinical outcome of the concomitant ankle instability of case 5 was excellent.

DiscussionOsteoid osteoma comprise approximately 5% of bone tumours, and 11% of benign tumours.1 In the foot they account for 2%–10% of the total,3,4 and prefer the hindfoot, and the talus in particular (30%–60%). Of all cases, 2%–3% are located in the calcaneus.18 The publications in this regard are usually isolated clinical cases in the talus6,7,9,12,13,15 or calcaneus,10,14,23 or series with few cases located in the area of the foot and ankle. Dimnjakovic et al.20 reported 6 OOs in the talus in a series of 9; Daniilidis et al.16 reported 3 in the talus, and 3 in the calcaneus in a series of 29; and Houdek et al.17 reported 5 in the talus, and 2 in the calcaneus in a series of 13. El-Mowafi et al.21 published 4 OOs in the talus and one in the calcaneus in a series of 50 intraarticular cases. Our series adds another 5 cases to those already published.

Most OOs are seated in the dorsal face of the neck and are subperiosteal forms,4,20 although there are also intramedullary cases and sites on the bearing surface of the body12 and its posterior segment.13 The nidus is usually intramedullary in the calcaneus, often subarticular.23,28,29 In our series, one of the 3 cases of the talus was located in the head, in a patient aged 50, which was also a variation from the norm, since this is not the usual age of presentation. One of those located in the calcaneus was intracortical.

In general, the epidemiological data and pain in OOs of the feet are similar to those of other cases in other skeletal sites.17 Those with a subperiosteal site usually involve synovitis and joint effusion. However, X-rays tend not to be diagnostic since there is often no periosteal reaction, cortical thickening and reactive medullary sclerosis around the nidus that characterises the same lesions in the appendiceal skeleton.11 For this reason, since the disease is rare, diagnosis can be delayed and confused, in the talus, with bone contusions, stress fractures, sprains, ankle impingement,13 inflammatory arthropathies11,18 and/or complex regional pain syndrome. In the calcaneus they have been confused with stress fractures, posterior impingement,26,27 arthritis, sprains and ligament avulsions.14 One of the cases of our series was initially diagnosed as a stress fracture (case 3), and 2 as sequelae of previous sprains (cases 2 and 5, the latter with associated ATFL tear). The mean delay in diagnosis of our cases from the onset of symptoms was more than a year, close to the 2 years cited in the references.17,21

In the event of clinical suspicion of an OO, a plain x-ray should be taken to discount another disease and then a CT, MRI and bone scintigraphy performed, the order is not important, and the radiologist should be informed of the suspicion.21 An isolated imaging test is insufficient and difficult to interpret,15,20 since the information it provides should be combined with that of other tests, and with the epidemiological and clinical data of the case. CT identifies and precisely locates the nidus.22 MRI enhances it with the administration of contrast and shows perilesional bone oedema and, occasionally, synovitis in a nearby joint. Bone scintigraphy, although non-specific and less useful for subperiosteal locations than the classical intramedullary sites, will show a focal area of abnormal metabolic activity.11 In this context, in most cases the diagnosis of an osteoid osteoma of the hindfoot is confirmed, without the need for a biopsy, when the nidus is shown and all the signs reported from the imaging tests are present, usually from the third month following the onset of symptoms.

Although OOs can resolve spontaneously over time and with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs over a long period of time, the discomfort and possible side effects of continuous medical treatment make other treatment options preferable, and these have a close to 100% success rate. In order to eliminate or destroy the nidus, the alternatives for the hindfoot include open resections,2 and minimally invasive procedures such as CT-guided RFA,8,16,19,24–26,29 alcoholisation,21 laser photocoagulation,27 trephining5 or arthroscopic resection.6,7,9,10,12 The percutaneous procedures require less postoperative immobilisation, less time non-weight bearing, and an earlier return to activities of daily living than the traditional surgical resection, because there is no bone loss or significant weakness of the adjacent structures. Moreover, they can be performed as an outpatient, without needing to admit the patient. For all of these reasons they are preferable, when possible.

RFA combines all the conditions to make it the first procedure to be considered.14,24–26 However, it has the disadvantage that the pathological diagnosis of the lesion cannot be confirmed,26 and it is contraindicated or risky when the nidus is located at least 1cm away from a main neurovascular bundle or the skin, where there is a risk of burning.17 Due to the proximity of the nidus to the skin it was discounted in the 2 talus cases of our series (cases 2 and 5), and initially in one of the calcaneal cases (case 3).

Proximity of the nidus to the joint cartilage could be another contraindication for RFA because it could cause chondral damage by thermal necrosis.17,21 We do not consider this a significant risk, because case 1 of our series has maintained an excellent clinical outcome 12 years after the thermoablation of a subtalar nidus,28 and no adverse effects have been reported in other published cases either.29

Intraarticular OOs, usually subperiosteal in the neck of the talus, are excellent candidates for resection using arthroscopic techniques.6,7,11,12,20 The advantages of arthroscopic resection include full visualisation of the excision of the nidus, the possibility of performing a synovectomy and obtaining appropriate samples for histopathological study.20 However, the samples obtained can be inadequate due to artefacts caused by instruments. Intramedullary lesions can also be accessed through bone tunnels made arthroscopically. Arthroscopic resection seems more demanding in the calcaneus and is not generally practiced, although a similar site to that of one of our patients has been published, where the nidus was accessed using a subtalar arthroscopic approach.10

Open surgical resection remains the treatment of choice for cases where there are doubts as to the diagnosis or contraindications, or failed previous percutaneous surgical techniques. For it to be successful it must be complete.9 When this can be ensured, it is justified as an alternative to any percutaneous technique. In one of the 2 cases of our series it was not successful due to a technical error when it was performed.

Our study's main limitation, apart from its retrospective nature and small sample size, was that there was no histological confirmation for the cases that were treated with RFA. However, as we have already mentioned, biopsy is not necessary for typical cases,26 although not all authors are of the same opinion.24 Another limitation is that the follow-up was short for certain cases, which means that later recurrences cannot be excluded, although the immediate results of all the techniques seem to have been maintained over time.20

To conclude, a diagnosis of OO of the hindfoot can be confirmed when the epidemiological, clinical and imaging data are compatible with the disorder. In the talus, where the majority of OOs are subperiosteal and the nidus can be near the skin, a simple intralesional resection (possibly arthroscopic) or en bloc resection are simple, minimally invasive and curative alternatives. RFA would be the treatment of choice for the calcaneus, where most cases are intracortical or spongy, without the need for histopathological study. A subchondral site does not seem to contraindicate the technique.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence ii.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Mellado-Romero MA, Vilá-Rico J, Gallego-Herrero C, Sánchez-Herraéz S, Casas-Ramos P, Santos-Sánchez JA, et al. Diagnóstico y tratamiento de los osteomas osteoides del retropié: un método terapéutico para cada caso. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2019;63:165–172.