Vertebral fractures in oncology patients cause significant pain and disability, with decreased quality of life. The aim of the study is to assess the efficacy and safety of kyphoplasty in this type of vertebral fracture in the acute phase.

Materials and methodsA retrospective study was conducted on 75 consecutive oncology patients with 122 acute vertebral fractures, who underwent bilateral balloon kyphoplasty, with a mean follow-up of 11 months.

ResultsAlmost all (91%) of the patients improved their pain level. The mean improvement in the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) was 4.28 points (preoperative value 7.49 [SD 1.19], postoperative 3.21 [SD 0.95]). Before surgery, 53% of patients needed major opioids (40 cases), and one month after surgery only 12% (9 patients) required them.

Quality of life determined by the Karnofsky index improved from 60.2 (SD 10) to 80.7 (SD 12.1). Cement leaks were found in 5.7% (7 cases), all without neurological repercussions. New fractures appeared in 11 patients. This subgroup showed a slight worsening of the initially acquired clinical improvement. No neurological or pulmonary complications related to surgical technique were found.

ConclusionsKyphoplasty is an effective and safe for treating vertebral fractures in patients with cancer.

Level of evidenceLevel IV.

Las fracturas vertebrales en pacientes oncológicos generan dolor e incapacidad, con limitación funcional y disminución de la calidad de vida. El objetivo del estudio es valorar la eficacia y seguridad de la cifoplastia en este tipo de fracturas vertebrales en el momento agudo.

Material y métodosEstudio descriptivo retrospectivo de 75 pacientes oncológicos consecutivos con 122 fracturas vertebrales agudas, que fueron tratados mediante cifoplastia percutánea bilateral con balón, con un seguimiento medio de 11 meses.

ResultadosSe produjo mejoría del dolor en el 91% de los pacientes. La mejoría media en la Escala Visual Analógica (EVA) fue de 4,28 puntos (valour preoperatorio 7,49 [DE 1,19], postoperatorio 3,21 [DE 0,95]). Antes de la intervención necesitaban opioides mayores un 53% de los pacientes (40 casos) y al mes de la cirugía solo un 12% (9 pacientes).

La calidad de vida determinada por el índice de Karnosfky mejoró de 60,2 (DE 10) a 80,7 (DE 12,1). En un 5,7% de las cifoplastias (7 casos) se encontraron fugas de cemento, todas ellas sin repercusión neurológica. Aparecieron nuevas fracturas en un 14% de las cifoplastias (11 casos). Este subgrupo presentó un empeoramiento discreto de la mejoría clínica adquirida inicialmente. No encontramos ninguna complicación neurológica ni pulmonar relacionada con la técnica quirúrgica que no estuviera justificada por la evolución de la enfermedad.

ConclusionesLa cifoplastia constituye un procedimiento eficaz y seguro para el tratamiento de las fracturas vertebrales en pacientes con cáncer.

Nivel de evidenciaNivel IV.

The skeletal system is the third most frequently affected organ by metastasis, following the lung and liver.1 Studies conducted in oncological patients reflect that up to 70% of cancer patients suffer vertebral metastases throughout the course of their disease, of which only 14% are symptomatic.2–4

The increased prevalence of cancer worldwide and the extended life expectancy of these patients has meant an increase in the incidence of bone metastases.5,6 Vertebral metastases generally appear between the ages of 40 and 65 years,7 with their most frequent location being the spinal column (60–80%).8,9 Approximately 60% of vertebral tumoral lesions are secondary to breast, lung and prostate cancers and myeloma.10,11 On the other hand, the incidence of vertebral fractures due to compression is estimated at 24% of patients with multiple myeloma, 14% in the case of breast cancer, 6% in prostate cancer and 8% in lung cancer.12 Thus, up to 50% of patients with myeloma present vertebral lesions, either by direct involvement or by fractures due to fragility.13,14

The traditional treatment of vertebral fractures by compression, based on rest and reduction of activity, often entails an unfavourable clinical and mechanical situation, persistent pain and decreased quality of life.15 In pathological fractures linked to vertebral metastasis, radiotherapy does not protect from progressive collapse, does not achieve restoration of height, and does not treat the associated instability.16 In such cases, balloon kyphoplasty manages to reduce pain, restores the height of the vertebral body and stabilises the spine, thus enabling an improvement in the level the activity of patients.17–19

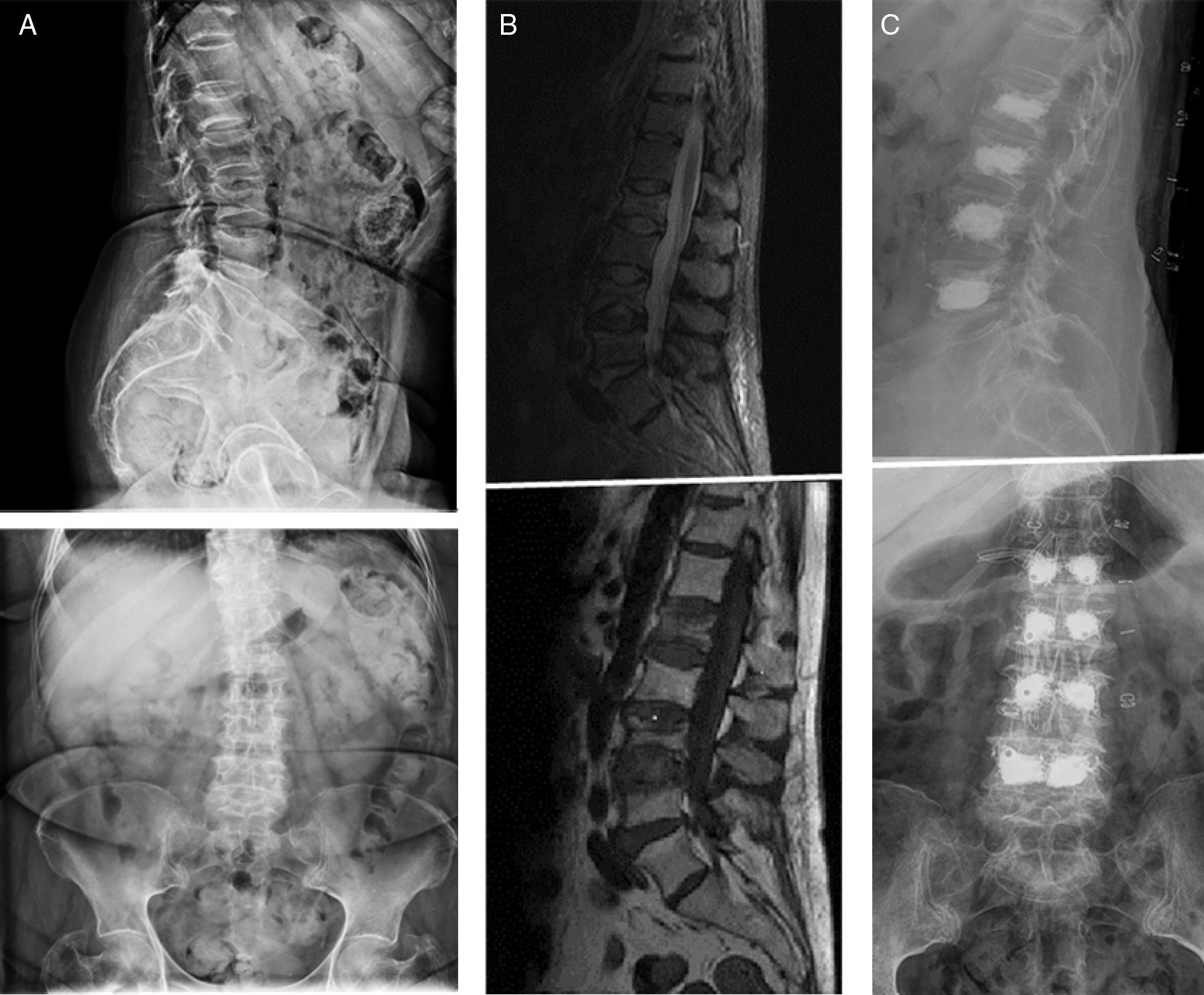

The objective of our study was to describe the effectiveness and safety of kyphoplasty in vertebral fractures among patients with cancer in our experience (Figs. 1 and 2).

(A) First left: patient with multiple myeloma and several vertebral fractures. (B) Centre: magnetic resonance imaging scan confirming the acute origin of the fractures (oedema). (C) Third right: percutaneous bilateral kyphoplasty, with a satisfactory radiographic result, with no associated complications.

We conducted a retrospective, descriptive study on 75 consecutive patients with metastasis or multiple myeloma affecting the spine who presented 122 acute vertebral fractures treated through kyphoplasty at our hospital between 2006 and 2012. The fractures in patients with multiple myeloma were assumed to be somehow linked to the tumoral disease.4,5 The diagnosis of vertebral fracture by acute compression was established by the presence of bone oedema in an MRI scan. We excluded from the study chronic fractures and those not subsidiary to treatment through balloon kyphoplasty due to involvement of the posterior wall or associated criteria of vertebral instability.20 Kyphoplasty in patients with vertebral metastasis was indicated in type I, II and IV fractures according to the Harrington classification,20 excluding those presenting neurological involvement, as well as in patients with intermediate scores (4–7 points) in the Tomita scale.21 Preoperative simple radiographs in 2 projections (anteroposterior and lateral) and centred on the affected vertebral level were obtained in all cases, as well as an MRI scan to specify the lesional level of the fracture, its acute character and the condition of the pedicles for the approach.5,22 The kyphoplasty was conducted with the patient in the prone position and either local (when 1 or 2 levels were treated) or general anaesthesia (when more than 2 levels were treated). The levels were approached through a percutaneous route with bilateral transpedicular access. Sitting and walking were authorised in the first 24h, with hospital discharge taking place during the following 24–48h. The mean follow-up period was 11 months (range: 3–36 months) (Table 1).

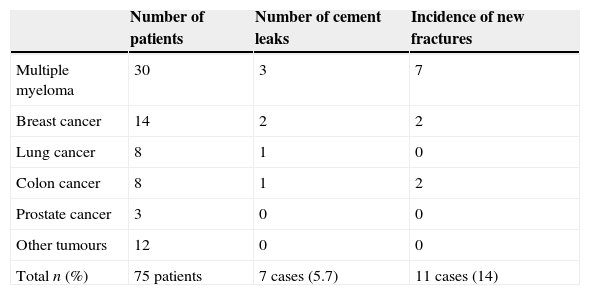

Results of complications observed according to the type of primary tumour.

| Number of patients | Number of cement leaks | Incidence of new fractures | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple myeloma | 30 | 3 | 7 |

| Breast cancer | 14 | 2 | 2 |

| Lung cancer | 8 | 1 | 0 |

| Colon cancer | 8 | 1 | 2 |

| Prostate cancer | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Other tumours | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Total n (%) | 75 patients | 7 cases (5.7) | 11 cases (14) |

The effectiveness of kyphoplasty was evaluated through a reduction in the intensity of pain, quality of life scales and the level of correction of vertebral body height. The results regarding pain improvement were evaluated according to a visual analogue scale (VAS) and the decrease in major opioid use following the surgery. Quality of life was evaluated according to the Karnofsky index. All the clinical results mentioned were recorded before the surgery, upon hospital discharge and at 9 or 12 months after the surgery. The height of the vertebral body was determined as a percentage of the reestablishment of said height by studying lateral radiographs of the affected spinal segment, at 9 or 12 months after the surgery. This was done by means of the technique described by the majority of existing studies,5,22,23 establishing the relationship between the preoperative and postoperative measurements, as well as that relative to the adjacent vertebrae.

In terms of safety, all the cement leaks were registered, even those not associated to neurological complications, along with the onset of new vertebral fractures and medical complications occurring in the immediate postoperative period. Cement leaks and the appearance of new fractures were assessed by studying conventional radiographies obtained on the first day after the intervention, in outpatient clinic 1 month after the surgery and subsequently every 3 months, until the end of the follow-up period.

All the data collection was carried out by an independent observer who did not perform any of the interventions, based on the clinical histories and the surgical protocols of each patient.

The statistical analysis of the data was carried out using the statistics software package SPSS version 15.0. The qualitative variables were described through the distribution of frequencies, whilst the quantitative variables were described through the mean and standard deviation (SD). Comparison of preoperative and postoperative qualitative and quantitative variables was done using the Anova and Mann–Whitney U techniques in non-normal conditions, and the Student t for paired samples under normal conditions. A value of P<.05 was considered as significant in all cases.

ResultsAmong the 75 patients there were 50 females (66.6%) and 25 males (33.3%), with a mean age of 68 years (range: 42–86 years). The tumoral diagnoses were the following: 30 multiple myelomas (40%), 14 breast cancers (18.6%), 8 lung cancers (10.6%), 8 colon cancers (10.6%), 3 prostate cancers (4%) and the remaining 12 (16%) were other solid tumours.

Out of the 122 fractures, the most frequently affected spinal segment was the lumbar region (63.1%; 77 patients), followed by the dorsal region (36.9%; 45 patients). In total, 54.6% of patients underwent kyphoplasty at a single level, 33.3% at 2 levels, 8% at 3 levels and 3.9% at 4 or more levels.

Pain was improved in 91% of patients, with a mean improvement of 4.28 points at the end of the follow-up period, going from 7.49 (SD 1.19) to 3.21 (SD 0.95). Prior to the intervention, 53% of patients (40 cases) required major opioids, 36% (20 cases) required minor opioids and 20% (15 cases) were taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Twelve months after the intervention, only 12% of patients (9 cases) required major opioids, whilst 42% (32 patients) did not use analgesia or did so only occasionally.

Quality of life, as determined by the Karnosfky index, went from 60.2 (SD 10) to 80.7 (SD 12.1), and this difference was statistically significant (P=.03).

The greater the number of fractured vertebrae, the greater the pain and preoperative limitation, and the lower the improvement after kyphoplasty. No statistically significant differences were observed between strata.

A total of 31 (25.4%) fractures presented radiographic improvement, with a recovery of 19.7% of the total height expected from the vertebral body. In the rest of cases we did not find any observable radiographic differences. These findings did not reach statistical significance (P=.07).

There were no neurological or pulmonary complications linked to the technique. There were cement leaks in 7 fractures (5.7%) and none of them had neurological repercussions. In 5 cases the leak was to an adjacent disc and 2 were anterior. Three took place in patients with multiple myeloma and 4 in metastatic patients. In relation to the base disease, 1 patient died after 3 months of follow-up, and 6 died after between 6 and 9 months. A total of 11 patients presented new fractures 9–12 months after the kyphoplasty; 7 in the context of multiple myeloma with limited worsening of the initial clinical improvement.

DiscussionNowadays, percutaneous balloon kyphoplasty is a standardised technique for the treatment of osteoporotic and acute vertebral fractures. Bouza et al.24 reflected this growing trend in Europe, with effectiveness and safety results which justified its use. The systematic review conducted by Robinson and Olerud25 concluded that neither kyphoplasty nor vertebroplasty can be considered as the gold standard for the treatment of vertebral osteoporotic fractures, since, despite offering initial improvements, the long-term clinical results are close to those of fractures treated without surgery. Svedbom et al.26 proved that, despite conservative treatment being more cost-effective and safer, the percutaneous treatment is indicated in hospitalised patients with acute fractures due to the improvement in symptoms and reduction in hospitalisation times.

However, very few studies focus on acute vertebral fractures in cancer patients, whether metastatic or related to multiple myeloma. We have included them because, in addition to those directly relayed to myeloma, vertebral lesions can also be caused by the osteopenia produced.23

In our study we found that kyphoplasty was an effective and safe procedure to treat vertebral fractures among cancer patients. All were acute fractures, diagnosed by MRI and in hospitalised patients.23,26

Our series included a considerable number of patients, all intervened by the same surgeon, but with methodological limitations (retrospective design, absence of a control group), which makes us cautious when presenting conclusions.

The patients presented a reduction in pain intensity evidenced by a decrease in consumption of major analgesics and improvement in the VAS (reduction of 4.28 points). There was an improvement in quality of life as assessed by the Karnosfky index, which went from 60.2 to 80.7 (P<.05). Pflugmacher et al.27 obtained similar results, although they used quick questionnaires for quality of life. Berenson et al.19 published a retrospective study with a control group, in which they compared the benefits of kyphoplasty versus non-surgical treatment of these fractures, and concluded that the former experienced a significant improvement in quality of life.

Pain reduction was maintained throughout the monitoring period, as reported by other authors.27–29 The appearance of new vertebral fractures produced a worsening of the quality of life achieved after the surgery, but it continued to be better than the initial value in all cases. The risk of a new fracture was higher among patients with multiple myeloma, due to the physiopathogenesis of the disease.23

The grade of reestablishment of the height of the vertebral body is scarcely relevant (except in isolated cases), both in number (25.4% of vertebrae treated), and in height (19.7%). Theoretically, an anatomical restitution would enable recovery of favourable biomechanical conditions. However, often this recovery is only of a few millimetres.27–29 This improvement is not maintained over time and presents considerable interobserver variability.5 There are multiple studies on kyphoplasties in osteoporotic fractures which have demonstrated a reestablishment of the height of the vertebral body,30 but there are none in relation to vertebral fractures by compression in cancer patients, in whom a similar or superior clinical improvement would be expected, with a lower restitution due to the aetiopathogenesis itself. Berenson et al.19 obtained improvements in the reestablishment of vertebral height in cancer patients, assessed 1 month after the surgery. This improvement was significant in the spinal column and in the dorsolumbar joint, and not significant at the lumbar level. In our study, we did not obtain significant changes at any vertebral level.

The low rate of medical, neurological and pulmonary complications reflects that kyphoplasty is a safe procedure. We did not find medical complications that were directly related to the technique. Wardlaw et al.31 published a rate of medical complications in non-operated patients which was very similar to that of intervened patients. The review of osteoporotic fractures conducted by Robinson and Olerud25 revealed more complications among patients treated by conservative treatment, due to a longer bed time.

There were 7 cases (5.7%) of cement leaks, but none was symptomatic. In 2 studies conducted in 2007 and 2008, Pflugmacher et al. published similar data regarding the treatment of metastatic fractures27 and of fractures related to multiple myeloma.29 A correct preoperative selection of patients, who should fulfil posterior wall stability and integrity criteria, is essential to minimise these complications, as is precaution when introducing volumes of cement over 5ml.5 Given the good clinical results in terms of reduction of pain and improvement of quality of life, it does not seem justified to attempt more ambitious corrections.

The appearance of new fractures causes clinical worsening. Patients with multiple myeloma presented a higher incidence of new fractures (23%). These data show that the incidence of new fractures after kyphoplasty is not higher than the incidence of new spontaneous fractures (between 19% and 24%).32 Berenson et al.19 and Wardlaw et al.31 published a similar incidence of new fractures in both groups.

Vertebral fractures in cancer patients are very present in clinical practice. Treatments based on major analgesics, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and orthosis are not always effective.1,6,9,10 Some clinical trials25,29 have reported similar rates of complications to those in any therapeutic speciality. These same studies expressed a rapid improvement of pain and capacity to stand, although the data tended to converge over time. This period works against patients with tumoral diseases, compromising their life prognosis. In addition, some studies of cost-effectiveness advocate treating acute fractures in hospitalised patients.26

Based on the foregoing, we conclude that balloon kyphoplasty represents an effective technique to reduce pain associated to vertebral fractures in cancer patients, enables a reduction of drug consumption and a rapid recovery of the previous quality of life. In addition, it is a safe technique, with an incidence of medical complications similar to that obtained through the orthopaedic, non-surgical management of these fractures.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation did not require experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that this work does not reflect any patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that this work does not reflect any patient data.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: García-Maroto R, García-Coiradas J, Milano G, Cebrián JL, Marco F, López-Durán L. Seguridad y eficacia de la cifoplastia en el tratamiento de la enfermedad tumoral de la columna vertebral. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2015;59:406–412.