Bullying is a serious psychosocial problem that impacts negatively on victims, and it is one of the main risk factors for the development of psychological problems and psychopathological symptoms in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. This study analyzes the mediating effect of self-esteem on the relationship between bullying victimization and the development of anxiety and depressive symptoms. The sample comprised 550 children and adolescents (56.5% women) aged between 10 and 17 years (M = 12.20, SD = 1.75) from the Basque Country, each of whom completed a battery of instruments consisting of a sociodemographic variables data sheet, a questionnaire for evaluating peer victimization, the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, and the Educational-Clinical Questionnaire: Anxiety and Depression. Results from structural equation modeling indicated that bullying victimization is a risk factor for developing anxiety and depression in childhood and adolescence, and also that the relationship between bullying victimization and these two emotional problems is mediated by self-esteem. This mediating effect of self-esteem is especially important in the case of depression, insofar as the effect of bullying victimization on depression is greater when mediated by self-esteem. The implications of the results are discussed, both for the field of educational psychology and in in relation to the psychological wellbeing of children and adolescents.

El bullying constituye un problema psicosocial muy grave que conlleva consecuencias negativas, siendo uno de los principales factores de riesgo para el desarrollo de problemas psicológicos y sintomatología psicopatológica tanto en la niñez y la adolescencia como en la edad adulta. En el presente estudio se pretende analizar el efecto mediador de la autoestima en la relación entre padecer acoso y desarrollar síntomas ansiosos y depresivos. Han participado 550 niños y niñas y adolescentes (56.5% mujeres) de entre 10 y 17 años (M = 12.20, DT = 1.75) de la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco, que han cumplimentado una batería de instrumentos compuesta por un cuestionario de variables sociodemográficas, un cuestionario para la evaluación de la victimización escolar, la escala para la medición de la autoestima de Rosenberg y el cuestionario Educativo-Clínico: Ansiedad y Depresión. Los resultados de los modelos de ecuaciones estructurales reflejan, por un lado, que sufrir bullying es un factor de riesgo para desarrollar ansiedad y depresión en la niñez y en la adolescencia. Por otro lado, confirman que la autoestima es una variable que media la relación entre el bullying y ambos problemas emocionales. Esta acción mediadora de la autoestima resulta de gran relevancia en el caso de la depresión, dado que el efecto que tiene el bullying sobre la depresión aumenta cuando está mediatizado por la autoestima. Se discuten las implicaciones de los resultados, tanto en el ámbito de la psicología educativa, como en el ámbito del bienestar psicológico de niños y niñas y adolescentes.

Bullying has been defined as repeated, intentional, aggressive behavior towards a peer that occurs in the context of an imbalance of power or strength (Smith et al., 2002). Research into bullying dates back almost fifty years (Olweus, 1973), and given the consistent finding of its highly negative impact on young people’s development, even to the extent of putting their lives at risk, recent years have seen a notable increase in the number of publications on this topic (Zych et al., 2015). There has also been growing interest in the design and implementation of programs to prevent bullying, both within Spain (Del Rey-Alamillo et al., 2018; Garaigordobil et al., 2016; González-Bellido, 2015; Montoya-Castilla et al., 2016; Piñuel & Cortijo, 2018; Sánchez-Ramos & Blanco-López, 2017), and internationally (Beane et al., 2008; Kärnä et al., 2011; Olweus & Limber, 2019), with a particular focus on the educational context (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011). However, bullying as a phenomenon is far from being eradicated (Garnefski & Kraaij, 2014).

Types of bullyingBullying can take several forms, the frequency of which varies according to sex and age. In the literature, bullying has been classified into physical (hitting, pushing, spitting), verbal (insulting, assigning nicknames), relational/social aggression (direct or indirect social exclusion, rumor spreading, ostracizing and exclusion from games), threats (through words or actions), object-focused (breaking or stealing personal belongings), sexual (groping or inappropriate sexual comments), and cyberbullying (via digital media) (Çalışkan et al., 2019; Cunningham, 2007; Magaz et al., 2016). The latter is becoming increasingly common and is of particular concern as it may occur 24/7 and be perpetrated by both known persons and strangers (Menesini et al., 2012; Tokunaga, 2010). A close relationship between cyberbullying and traditional bullying (which covers the other behaviors mentioned above) has been reported (Smith et al., 2008; Ybarra & Mitchell, 2004), and being a victim of traditional bullying is a predictor of cyberbullying victimization (Pornari & Wood, 2010).

Regarding the sex of victims, research has found that boys are more likely to suffer threats, intimidation, physical aggression, and attacks on personal belongings (Çalışkan et al., 2019; Lemstra et al., 2012; Pells et al., 2016), whereas girls are at greater risk of verbal abuse and social exclusion (Çalışkan et al., 2019; Lemstra et al., 2012; Vessey & O’Neill, 2011). No differences by sex have been found for cyberbullying victimization (Gradinger et al., 2009; Li, 2006).

Age also appears to influence the type of bullying that is perpetrated or experienced. In early life, aggression is invariably physical as children have yet to develop their verbal skills (Coyne et al., 2010), but as their language develops, verbal aggression tends to predominate. During the preschool years, when boys and girls begin to establish more peer relationships, indirect forms of aggression are increasingly common, and these behaviors become more subtle and complex during adolescence. Cyberbullying also emerges at a later stage, around the age that children begin to have access to digital devices and media, which is increasingly earlier (Barlett & Coyne, 2014).

Psychopathology associated with bullying victimizationBullying is acknowledged to be a serious psychosocial problem that impacts negatively on victims. Indeed, bullying victimization is considered to be one of the main risk factors for the development of psychological problems and psychopathological symptoms, not only during childhood and adolescence but also later in adult life. Specifically, research has found that victims of bullying are more likely to experience academic difficulties (Schwartz et al., 2005), anxiety (Coelho & Romao, 2018), psychosomatic symptoms such as insomnia or headache (Natvig et al., 2001), depression (Brunstein Klomek et al., 2019; Sweeting et al., 2006), self-harm behavior and suicide ideation (Bang & Park, 2017; Obando et al., 2018; Pedreira-Massa, 2019), psychosis (Bang & Park, 2017), eating disorders (Lie et al., 2019), and post-traumatic stress symptoms (Houbre et al., 2006). They also tend to show poorer emotional adjustment (Khatri et al., 2000) and lower self-esteem, especially in the social sphere (Estévez et al., 2009; Kowalski & Limber, 2013). An integrative review of qualitative research into the emotional experience of bullying victimization found that self-esteem issues were documented in 50% of the studies analyzed (Hutson, 2018).

Among the problems studied, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation are the most commonly cited emotional consequences of bullying victimization (Bottino et al., 2015; Moore et al., 2017). In this context, a recent systematic review reported a clear relationship between cyberbullying victimization and suicide behavior in adolescents (Buelga et al., 2022), while another study found that among victims of cyberbullying, more than half had suicidal ideation and almost 20% had attempted suicide (Nagamitsu et al., 2020). There is also increasing evidence that being bullied during childhood can have a long-lasting negative impact on victims’ wellbeing, with the consequences persisting into adulthood (Copeland et al., 2013).

There are several theoretical models aimed at explaining the association between peer victimization and depression. The symptoms-driven model (Kochel et al., 2012; Sentse et al., 2017) proposes that depressive symptoms interfere with young people’s social development and promote difficulties in peer relationships. The recent study by Kochel and Rafferty (2020) is one of the first to provide empirical support for this model, showing specifically that social helplessness mediates the contribution of depressive symptoms to subsequent peer victimization. In models based on interpersonal risk (Troop-Gordon et al., 2015), the focus is on how peer victimization contributes to depressive symptoms. Specifically, the hopelessness theory of depression (Abramson et al., 1989; see Liu et al., 2015 for a review) suggests that individuals who respond to negative life events with maladaptive inferences and behaviors may come to experience hopelessness, which in turn leads to depression. Thus, for example, a child who attributes a negative event such as being bullied to their own lack of social competence and who believes they are destined to be victimized may shy away from social relations and experience sadness and apathy due to a sense of hopelessness. There are also transactional models of the association between peer victimization and depression (Kawabata et al., 2014).

As already noted, another emotional problem that has been closely linked to peer victimization is anxiety. In the case of social anxiety, it has been suggested that this may be both a precursor and consequence of victimization (Wichstrøm et al., 2013). Drawing on the theoretical model underpinning schema therapy (Young et al., 2003), Calvete et al. (2018) examined the role of maladaptive schemas (highly prevalent among adolescents who suffer from social anxiety) as a mediational mechanism in the relationship between social anxiety and bullying victimization, as well as the contribution of social anxiety to continued victimization. Although social anxiety did not emerge as a factor in the persistence of bullying victimization, it did predict victimization when mediated by maladaptive schemas. Bullying victimization was also associated with increased social anxiety over time. In a more recent study, Barzeva et al. (2020) examined the role of peer victimization and acceptance in the relationship between social withdrawal and social anxiety. They concluded that negative peer experiences predict increased social withdrawal.

In contrast to the considerable number of studies showing a relationship between peer victimization and both anxiety and depression, very few have considered variables related to victims’ perceptions of self, such as shame and self-esteem, when seeking to elucidate the mechanisms underpinning the psychosocial impact of bullying victimization (Wu et al., 2021).

Self-esteem as a mediating factorSelf-esteem has been defined as a positive or negative attitude toward the self as a whole (Rosenberg, 1965). Accordingly, people with positive self-esteem are satisfied with themselves as individuals and feel a strong sense of self-worth, whereas the opposite is true of individuals low on self-esteem, who tend to disparage their own abilities and qualities. In two meta-analyses of longitudinal studies on peer victimization and self-esteem, van Geel et al. (2018) concluded that victimization of this kind may lead to lower self-esteem because negative appraisals by peers become internalized (Overbeek et al., 2010; Salmivalli et al., 1999). They also suggested that the results of their meta-analyses might be indicative of a negative cycle between self-esteem and peer victimization, wherein victimization lowers self-esteem, and wherein young people with lowered self-esteem are more vulnerable to further victimization.

Regarding explanations for the association between peer victimization, self-esteem, and anxiety and depression, some authors have suggested that the shame, guilt, frustration, and fear that victims of bullying often feel (Irwin et al., 2016; Strøm et al., 2018) leads to lower self-esteem (Jones et al., 2014; Tsaousis, 2016), which in turn has been reported to be an important predictor of social anxiety in these individuals (Bowles, 2016; Hiller et al., 2017). Various studies have also found that low self-esteem is a risk factor for depressive symptoms (Orth et al., 2014; Zhong et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2020). In the literature there are two main explanatory models of the relationship between low self-esteem and depression. The vulnerability model proposes that negative self-evaluations constitute a causal risk factor for depression (Beck, 1967; Butler et al., 1994; Metalsky et al., 1993), whereas the scar model hypothesizes that low self-esteem is a consequence, not a cause, of depression, insofar as depressive episodes may leave permanent scars in a person’s self-concept (Coyne et al., 1998; Rohde et al., 1990). It is important to note that the two models are not mutually exclusive, because the processes they describe may occur simultaneously.

Mention should also be made of two theories that could explain why depression and anxiety are differentially related to self-esteem. According to the tripartite model of anxiety and depression (Clark et al., 1994), this would be because anxiety is only associated with negative affect, whereas depression, like self-esteem, is related to both positive and negative affect (Watson et al., 2002). The second theory, the cognitive content specificity hypothesis (Beck et al., 1992), proposes that depressive cognitions reflect negative evaluations about the self, the world, and the future, whereas anxious cognitions reflect the anticipation of a physical or psychological threat. Consequently, low self-esteem should be more closely related to depression than to anxiety. The results of the meta-analysis by Sowislo and Orth (2013) provide solid support for the vulnerability model of the relationship between low-self-esteem and depression. The authors also conclude that the association between low self-esteem and anxiety is bidirectional and of smaller magnitude than is the association with depression.

Despite the importance of self-esteem in people’s lives and the large number of studies that support its association with emotional problems, scant attention has been paid to the possible mediating effect of self-esteem on the relationship between bullying victimization and anxiety and depression, and very few studies have sought to examine this effect empirically. A further issue to consider is that various authors have found that levels of self-esteem (Bleidorn et al., 2016; Kling et al., 1999; Quatman & Watson, 2001), depression (Hyde et al., 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000), and anxiety (Lewinsohn et al., 1998; McLean et al., 2011) vary across sex. However, among studies that analyze the relationship between these constructs, some report sex effects (Gao et al., 2022; Moksnes & Espnes, 2012; Russo et al., 1993), while others have observed no differences between boys and girls (Sowislo & Orth, 2013). The same applies to research on the relationship between peer victimization and the variables analyzed in the present study: some authors report sex differences (Bernasco et al., 2022; Yen et al., 2013), whereas others do not (Forbes et al., 2019; Storch et al., 2003).

The present studyIt is clear from the above review that peer victimization can have a serious negative impact on a young person’s mental and physical health, even placing their life at risk, and this underlines the importance of understanding the consequences of bullying and the factors that may heighten its effects. In this context, the primary aim of the present study is to analyze the relationship between peer victimization and anxiety and depression, two emotional disorders that can severely undermine the wellbeing of children and adolescents. However, in order to design adequate intervention programs that take into account and seek to address the factors that contribute to the effects of bullying victimization, it is essential to identify the variables which can help to explain why being bullied may lead to anxiety and depressive symptoms. To this end, the present study focuses specifically on the role of self-esteem in this process. Based on the extant literature, we expect to find that bullying victimization is positively associated with anxiety and depression. In addition, we hypothesize that self-esteem will act as a mediating variable in this relationship and, therefore, that it is one of the variables that contributes to the emotional problems experienced by victims of bullying.

MethodParticipantsSampling for this study was intentional so as to ensure that different stages of education within the target population (i.e., children and adolescents resident in the Basque Country) were represented. Participants were 550 children and adolescents (56.5% female) aged between 10 and 17 years (M = 12.20, SD = 1.75) who were recruited from across six schools in the Basque Country; 50.7% were still attending elementary school (28.2% in year 5 and 22.5% in final year 6), while the remainder (49.3%) were enrolled in secondary education (17.1% in year 1, 7.1% in year 2, 12.5% in year 3, and 12.5% in year 4). Immigrant children accounted for 5.8% of the sample, and 6.5% of participants had repeated at least one school year. Regarding family, 10.4% had no siblings, 60.5% had one, 23.4% had two, and 5.7% had three or more. The large majority of children (86.7%) lived with both parents, while of the remainder, 1.1% lived with just the father, 7.9% with just the mother, and 4.3% with other persons such as grandparents, a parent and their current partner, or other relatives. In terms of parents' educational background, 46.8% of fathers and 56.2% of mothers had higher education, 37.9% of fathers and 33.6% of mothers had completed secondary education, and 15.3% of fathers and 10.2% of mothers had only elementary schooling. The required sample size was estimated according to the recommendations of Wolf et al. (2013), which indicated that a total of 460 participants would be sufficient to detect a direct effect of .25, an indirect effect of .06, and an R2 of .16 with a significance level of .05 and power of 95% for direct effects and 84% for indirect effects.

InstrumentsSociodemographic data sheet. An ad hoc data sheet was used to collect information about the following sociodemographic variables: sex, age, place of birth, whether the student had repeated one or more school years, educational level and current employment status of both parents, and composition of the family unit.

Questionnaire for evaluating peer victimization (ISEI-IVEI, 2012). This instrument evaluates 19 behaviors relating to five types of bullying (verbal harm, social exclusion, physical harm, damage to personal belongings, and cyberbullying). For each behavior, respondents rate the frequency with which they have been the victim of it, witnessed it, and perpetrated it, in each case using a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = Never, to 4 = All the time. The total score for each perspective (i.e., victim, witness, perpetrator) therefore ranges between 19 and 76. In the present study, participants were only required to respond to the items referring to being the victim of these behaviors (e.g., “Jo egiten naute [They hit me]”, “Iraintzen naute [They insult me]” or “Gauzak hausten dizkidate [They break my things]”). A general index of victimization was calculated based on the proportion of students who endorsed the option ‘Often’, or ‘All the time’ for at least one of the 19 behaviors. In the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha for this questionnaire was .90, McDonald’s omega and the composite reliability index were both .97, and the average variance extracted was .64.

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965; used here in its Basque version: Apodaka, 2004). This scale comprises 10 items that measure overall feelings, both positive and negative, about the self (e.g., “Gauzak besteek bezain ondo egiteko gai naiz [I'm able to do things as well as most other people]” or “Oro har, neure buruarekin pozik nago [On the whole, I’m satisfied with myself]”). Each item is rated on a Likert-type scale anchored by 1 = Strongly disagree, and 4 = Strongly agree, and hence the total score ranges between 10 and 40. Items referring to negative self-appraisals were recoded to align with positively worded items, and thus a higher scale score indicates higher self-esteem. In the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .76, McDonald’s omega and the composite reliability index were both .86, and the average variance extracted was .39.

Educational-Clinical Questionnaire: Anxiety and Depression (CECAD; Lozano et al., 2013; used here in its Basque version – Gorostiaga et al., 2018). This is a 49-item instrument that measures Anxiety (20 items) and Depression (29 items) in persons aged 7 and over. Examples of items include: “Asko kostatzen zait lo egitea [I find it really hard to sleep]” (anxiety) and “Dena gaizki egiten dudala pentsatzen dut [I feel I don’t do anything right]” (depression). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (from 1 = Never, to 5 = All the time), and hence total scores range between 20 and 100 for anxiety and between 29 and 145 for Depression. Both the original and the Basque version of the instrument have shown adequate psychometric properties. In the present sample, and for the anxiety and depression dimensions respectively, Cronbach’s alpha was .86 and .92, McDonald’s omega was .78 and .92, the composite reliability index was .89 and .88, and the average variance extracted was .30 and .28.

ProcedureParticipants completed the battery of instruments in a single, group session in their respective schools, in a supervised setting that ensured the anonymity of responses. The instruments were administered in the following order: sociodemographic data sheet, Basque version of the CECAD, Basque version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, and the peer victimization questionnaire. Data from 45 students were eliminated from the analysis as they had not responded to more than 5% of the items on at least one of the measures. In the remaining cases, any missing values were imputed. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects of the University of the Basque Country.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics and correlations were computed using SPSS 27. The fit of the measurement model that included the variables victimization, self-esteem, and anxiety and depression, as well as the fit of the structural equation model that included victimization as a predictive variable, self-esteem as a mediating variable, and anxiety and depression as criterion variables, were evaluated using Mplus 7. The associations between latent variables in the structural equation model were estimated controlling for sex and age. Because these data are ordinal and do not follow a normal distribution, we used the weighted least squares means and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator for the analysis. Model fit was assessed using the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Threshold values for considering acceptable good model fit are: TLI and CFI ≥ .90; RMSEA ≤ .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Although we also calculated the χ2 statistic, its value was not considered for the evaluation of model fit as it is highly sensitive to sample size. Finally, we performed bootstrapping with 2000 replications to calculate 95% confidence intervals and to assess the significance of the indirect effects. An effect was considered statistically significant if the confidence interval did not include zero. Missing values were replaced by the mean for the corresponding dimension.

It should be noted that prior to analyzing data for the whole sample, we carried out a descriptive analysis to determine whether the distribution of the variables sex, age, and stage of education was similar across all participating schools. Analysis of variance was also performed to examine if there were notable differences between schools in students’ scores on anxiety, depression, and self-esteem. As no important differences between schools were observed, we proceeded to analyze data for the sample as a whole.

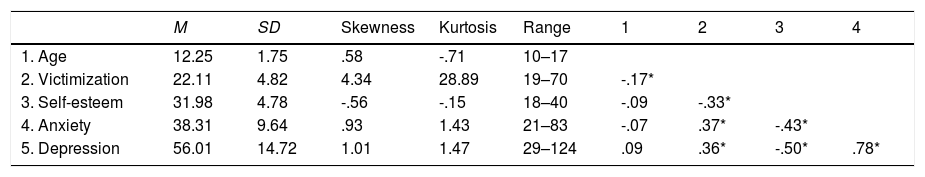

ResultsDescriptive statistics and correlationsTable 1 shows descriptive statistics for the whole sample regarding age, victimization, self-esteem, anxiety, and depression, as well as bivariate correlations between the variables.

Descriptive statistics and Spearman correlations

| M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 12.25 | 1.75 | .58 | -.71 | 10–17 | ||||

| 2. Victimization | 22.11 | 4.82 | 4.34 | 28.89 | 19–70 | -.17* | |||

| 3. Self-esteem | 31.98 | 4.78 | -.56 | -.15 | 18–40 | -.09 | -.33* | ||

| 4. Anxiety | 38.31 | 9.64 | .93 | 1.43 | 21–83 | -.07 | .37* | -.43* | |

| 5. Depression | 56.01 | 14.72 | 1.01 | 1.47 | 29–124 | .09 | .36* | -.50* | .78* |

M = mean; SD = standard deviation; Range = score range; Age = chronological age in years.

As expected, bullying victimization was positively correlated with anxiety and depression, and negatively correlated with self-esteem. In addition, self-esteem showed a strong negative correlation with both anxiety and depression. Regarding the prevalence of bullying, represented here by the general index of victimization, 14.9% of the students surveyed reported being the victim of at least one of the behaviors considered.

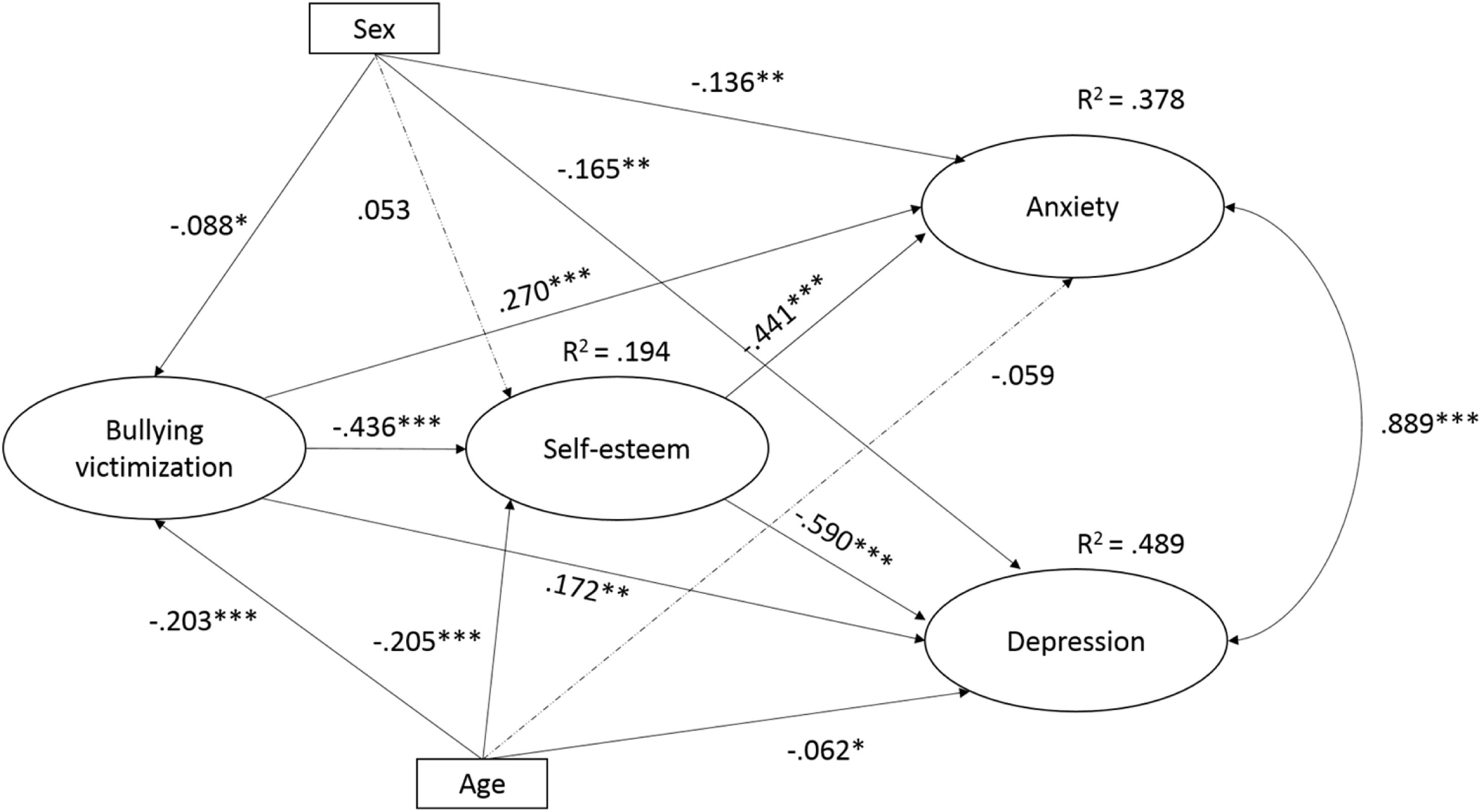

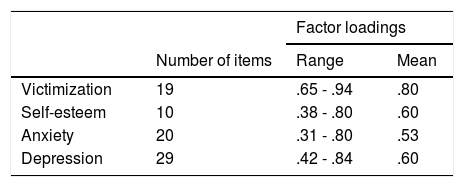

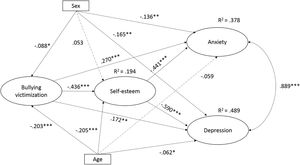

Structural equation analysisThe measurement model showed a good fit, χ2(2750) = 3659.28, p < .001, CFI = .95, TLI = .95, RMSEA = .026 [90% CI .023, .028], and as can be seen in Table 2, item loadings on their respective factors were adequate (Supplementary Table 1 details all the standardized factor loadings). Figure 1 shows the structural model, including the standardized coefficients for each of the relationships between latent variables.

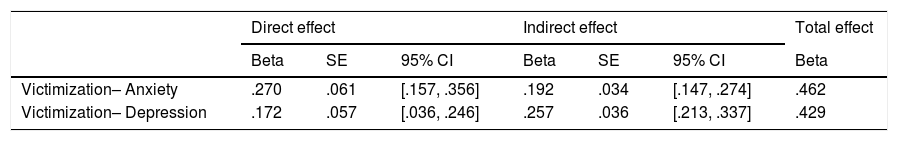

The mediation model displayed in Figure 1 also showed a good fit, χ2(2898) = 4008.56, CFI = .94, TLI = .94, RMSEA = .028, p < .001, 90% CI [.025, .030]. Furthermore, all the relationships in the model were statistically significant and in the direction predicted by theory. Regarding direct effects, bullying victimization had a moderate effect on anxiety, and a slightly weaker effect on depression. With respect to self-esteem, this variable had a significant mediating effect in predicting both anxiety and depression. Moreover, when mediated by self-esteem, the effect of bullying victimization on depression was stronger than the corresponding direct effect. This was not the case for anxiety, as here the direct effect of bullying victimization was a stronger predictor than was the effect mediated by self-esteem. Table 3 shows the direct, indirect, and total effects in the mediation model.

Standardized direct, indirect, and total effects

| Direct effect | Indirect effect | Total effect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SE | 95% CI | Beta | SE | 95% CI | Beta | |

| Victimization– Anxiety | .270 | .061 | [.157, .356] | .192 | .034 | [.147, .274] | .462 |

| Victimization– Depression | .172 | .057 | [.036, .246] | .257 | .036 | [.213, .337] | .429 |

SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval.

This study has examined the association between peer victimization and anxiety and depression in a sample of children and adolescents from the Basque Country, the aim being to determine the role of self-esteem in this relationship. A meta-analysis that examined protective factors against bullying and cyberbullying concluded that high self-esteem is one of the individual factors associated with a lower risk of victimization (Zych et al., 2015). Accordingly, various studies have linked low self-esteem to a higher risk of bullying victimization (Estévez et al., 2009; Hutson, 2018; Kowalski & Limber, 2013; Wu et al., 2021). These findings underline the importance of analyzing the contribution of self-esteem to the emotional problems suffered by victims of bullying.

The results of the present study show that bullying victimization is positively and significantly associated with anxiety and depression, corroborating both our first hypothesis and previous research on this topic (Arseneault et al., 2010; Bottino et al., 2015; Lereya et al., 2013; Moore et al., 2017). In addition, and in line with our second hypothesis, self-esteem was found to be a mediating variable in the relationship between bullying victimization and both anxiety and depression. This mediating effect has been observed previously in a small number of studies (Wu et al., 2021; Zhong et al., 2021), and the present research therefore adds to knowledge about the mechanisms through which peer victimization exerts its effects.

Our findings are also consistent with prior studies showing a negative relationship between self-esteem and anxiety (Greenberg et al., 1992). Harter (1999) argues that young people’s self-esteem is shaped primarily by two factors: self-perceived competence in important areas and the availability of social support. Accordingly, individuals with low self-esteem who feel incompetent and inferior to others, and who, as victims of bullying, also perceive a lack of social support, will find it more difficult to cope with stressful events, and as a result they will be more fearful and anxious about the future (Sowislo & Orth, 2013).

With respect to depression, the observed mediating effect of self-esteem is consistent with both the hopelessness theory of depression (Abramson et al., 1989; Liu et al., 2015) and the vulnerability model (Beck, 1967; Butler et al., 1994; Metalsky et al., 1993). This model posits that low self-esteem can heighten depression through both interpersonal and intrapersonal mechanisms. Regarding the former, research suggests that people with low self-esteem tend to seek negative feedback from others that confirms their negative self-view; this can lead to feelings of rejection and a loss of social support, increasing their risk of depression (Giesler et al., 1996). One of the intrapersonal mechanisms that has been linked to depression is self-focused attention (Mor & Winquist, 2002), and research has shown that people with low self-esteem tend to think repetitively about their negative qualities, which can lead them to develop depressive symptoms (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000). A final point to note here is that, in contrast to what we observed for anxiety, our results showed that the effect of bullying victimization on depression was stronger when mediated by self-esteem, which is consistent with the vulnerability model.

Limitations and implications of the studyThis study has a number of limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design means that no causal inferences can be drawn from the results. Second, all the data are based on self-reports. Although self-report questionnaires for assessing anxiety and depression have shown adequate discriminant and convergent validity (Hodges, 1990), the use of other data collection methods, such as individual interviews, would strengthen the reliability of our findings. Third, the sample is not representative of the Basque population as a whole, and hence the results need to be replicated with samples of different characteristics and in other cultural contexts. Finally, the addition of another mediating variable to the model, for example, social support, resilience or shame, would enable a deeper understanding of why bullying can lead to anxiety and depression in victims.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the present study provides further evidence of the relationship between bullying victimization and anxiety and depression, and more importantly, it adds to knowledge about the mechanisms underpinning this relationship in children and adolescents. Given the frequency with which bullying occurs in the educational context, it is vital that all schools have protocols in place for detecting this behavior and for supporting victims and their families. There are now numerous programs aimed at preventing bullying, with notable examples being the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (Olweus & Limber, 2019), the Bully Free Program (Beane et al., 2008), and the KiVa program (Kärnä et al., 2011). Similar programs in Spain include the TEI (Programa de Tutoría Entre Iguales [Peer Tutoring Program]; González-Bellido, 2015), the AVE (Programa de prevención del Acoso y Violencia Escolar [Preventing Bullying and Violence at School]; Piñuel & Cortijo, 2018), the PREDEMA (Programa de Educación Emocional Para Adolescentes: De la Emoción al Sentido [Emotional Education Program for Adolescents: From Emotion to Meaning]; Montoya-Castilla et al., 2016), Cyberprogram 2.0 (Garaigordobil et al., 2016), Buentrato [Treat Others Well] (Sánchez-Ramos & Blanco-López, 2017), and Asegúrate [Stay Safe] (Del Rey-Alamillo et al., 2018), the goal of which is to promote attitudes, behavior, and relationships based on mutual respect so as to encourage more positive social interaction and reduce the incidence of bullying (Espinosa et al., 2021). Although these programs are clearly important, they are unlikely to eradicate the problem of bullying, whether inside or outside schools. Consequently, and given the important role that self-esteem plays in the development of anxiety and depressive symptoms, we believe that bullying prevention programs need to be complemented by interventions aimed at enhancing the self-esteem of victims of bullying, helping them to overcome their feelings of inferiority and apathy.

In conclusion, the results of this study show that bullying victimization is a risk factor for the development of anxiety and depressive symptoms in childhood and adolescence, and also that the relationship between bullying victimization and these two emotional problems is mediated by self-esteem. This mediating effect of self-esteem is especially important in the case of depression, insofar as the effect of bullying victimization on depression is greater when mediated by self-esteem. These findings contribute to knowledge about the mechanisms through which peer victimization may lead to anxiety and depression in young people.