Numerous studies support the benefits of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) in children and adolescents. Recent meta-analyses on the efficacy of these interventions in educational settings have found significant improvements in cognitive and behavioral measures with effect sizes ranging from small to moderate. However, no meta-analyses have evaluated the efficacy of MBIs in the Spanish educational setting. In this study, a systematic search of published articles and doctoral theses was performed through March 2022, with randomized controlled trials (RCTs) as an eligibility criterion. Eighteen studies with 1471 participants were included in the three-level meta-analysis. The overall average effect size was significant (g = 0.62), and significant effect sizes were obtained for all dimensions except for the mindfulness skills dimension, which included the following variables: personal and social development (g = 0.84), mood states (g = 0.44), cognitive functions (g = 0.67), emotional intelligence (g = 0.61), emotional and behavioral adjustment (g = 0.54), and mindfulness skills (g = 0.51). The analysis of the moderating variables showed that all the MBI types analyzed have significant effects, especially among the older participants, and that engaging in home practice and increasing the session duration in minutes improves their effectiveness. The results are relevant for research and for the implementation of mindfulness-based intervention programs in educational centers.

Existen numerosos estudios cuyos resultados apoyan los beneficios de las intervenciones basadas en mindfulness (MBIs) en niños y adolescentes. Recientes meta-análisis sobre la eficacia de estas intervenciones en contextos educativos encuentran mejoras significativas en medidas cognitivas y conductuales con tamaños de efecto que varían de pequeños a moderados. Sin embargo, no existen meta-análisis que evalúen la eficacia de las MBIs en el ámbito educativo español. En este estudio se ha realizado una búsqueda sistemática de artículos publicados y tesis doctorales hasta marzo de 2022, incluyendo como criterio de elegibilidad los ensayos con diseño controlado aleatorizado (RCTs). En el meta-análisis de tres niveles se han incluido 18 estudios con un total de 1471 participantes. El tamaño de efecto promedio global ha sido significativo (g = 0.62), además se han obtenido tamaños de efecto significativos para todas las dimensiones excepto para la dimensión habilidades de mindfulness: desarrollo personal y social (g = 0.84); estados de ánimo (g = 0.44); funciones cognitivas (g = 0.67); inteligencia emocional (g = 0.61); ajuste emocional y conductual (g = 0.54); habilidades de mindfulness (g = 0.51). El análisis de las variables moderadoras muestra que todos los tipos de MBIs analizados tienen efectos significativos, especialmente entre los participantes de mayor edad, y que la realización de prácticas en casa y el aumento de la duración en minutos de las sesiones mejora su eficacia. Los resultados son relevantes para la investigación y para la implementación de programas de intervención basados en mindfulness en centros educativos.

Recently, in the Spanish educational system, various educational reforms have introduced the need for training in emotional education competencies (LOMCE, 2013; LOMLOE, 2020). In recent decades, numerous interventions have been published based on mindfulness applied to the educational setting (Burke, 2010; Felver et al., 2016; Waters et al., 2015). There is growing interest in obtaining evidence of the effectiveness of this intervention type in the Spanish educational context (Landazabal, 2018; Langer et al., 2015). However, to date, no meta-analyses have evaluated the effectiveness of these mindfulness-based intervention (MBI) programs applied in the Spanish educational system.

Currently, the term mindfulness is commonly used, but an agreed-upon definition of it is difficult to find. According to Kabat-Zinn (2003), it is “the awareness that arises from intentionally paying attention to experience as it is in the present moment, without judging it, without evaluating it and without reacting to it” (p. 145). Its origins can be traced back 2,500 years to the Buddhist philosophy of Siddhartha Gautama, although in recent practices in the West, it has become detached from its religious origins. Dr. Kabat-Zinn designed a mindfulness-based stress reduction program (MRSB; Kabat-Zinn, 1982, 2003) to reduce stress and related disorders in the clinical setting. This program has been the basis for the emergence of other mindfulness-based intervention programs, including mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT; Segal et al., 2002), acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; Hayes et al., 2005) and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT; Linehan, 1993).

In the educational context, several reviews have been conducted on the efficacy of MBIs with randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and most authors agree on the benefits of these interventions for adolescents and children. However, these same reviews also note that caution should be exercised when generalizing the results due to the methodological limitations found in the reviewed studies (Burke, 2010; Felver et al., 2016; Langer et al., 2015). Currently, some meta-analyses have been conducted on the efficacy of mindfulness interventions in youth. Zoogman et al. (2014) analyze 20 RCT and non-RCT studies, and conclude that mindfulness interventions with youth are effective with small to moderate effect sizes. Zenner et al. (2014) review 24 studies and conclude that MBIs in children and youth are promising, particularly in relation to improving cognitive performance, resilience, and stress, with small to large effect sizes, but these interventions are not significant when used to reduce emotional problems. Klingbeil et al. (2017) analyze 76 RCT and non-RCT studies with participants younger than 18 years in school and clinical settings; overall, they report that MBIs produce small effects in studies using pre–post and RCT designs. Maynard et al. (2017), in their review of 61 studies with participants aged 4-20 years, indicate that MBIs have a small, positive, significant effect on cognitive and socioemotional skills but find no significant effect on academic and behavioral outcomes. In a recent meta-analysis on the efficacy of MBIs in children and adolescents, Dunning et al. (2019) select 33 RCT studies and find significant positive effects of MBIs for mindfulness, executive functioning, attention, depression, anxiety/stress, and negative behaviors, with small effect sizes. However, when considering only those studies with active control groups, significant improvements are only presented for mindfulness, depression, and anxiety/stress, with small to medium effect sizes.

This review of the literature shows that no meta-analysis of mindfulness-based interventions in education has been carried out in Spain to date. The present research aims to fill this gap in knowledge. It is based on the hypothesis that the regular practice of mindfulness applied in the Spanish educational environment would lead to a series of improvements in students. Thus, the aim of this research is to conduct a meta-analysis on the effectiveness of MBIs at different educational levels in Spain, including articles up to June 2021. To achieve this objective, a series of variables that may influence the effectiveness of the intervention programs are analyzed: type of mindfulness-based training program, age and educational level of the participants, duration of the sessions, home practice, control group design and type of dependent variables.

MethodStudy inclusion and exclusion criteriaThis meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the PRISMA statement (Moher et al., 2009). This meta-analysis has no previous record in specific databases, and there is no published review protocol. The inclusion criteria are as follows:

- •

Study design: at least one treated and one control group with pre- and posttest measures; RCTs.

- •

Participants: Spanish students in kindergarten, primary education, secondary education, high school or university.

- •

Interventions: at least one must be based on mindfulness.

- •

Results: quantitative results are used to calculate the effect size.

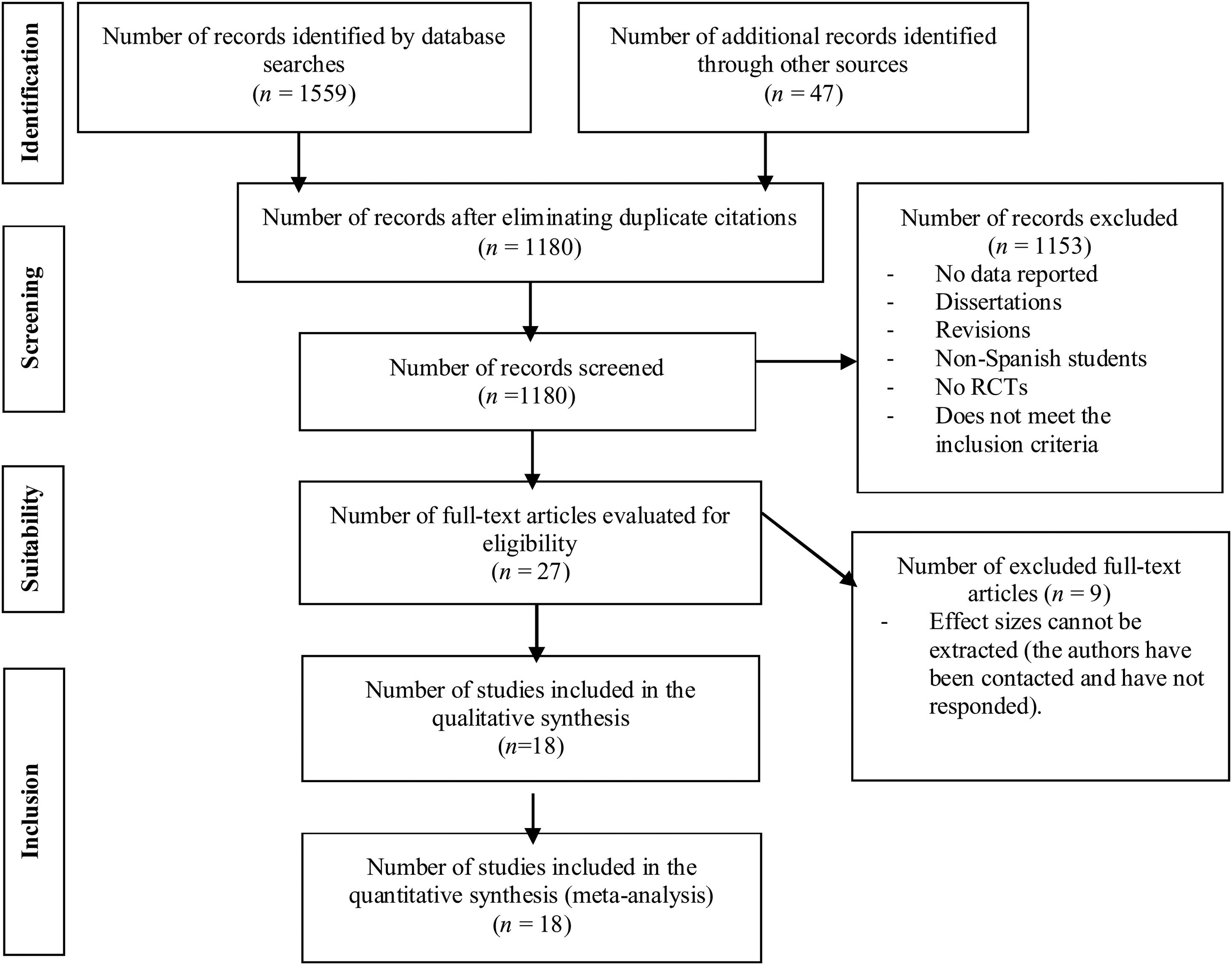

A total of 1606 studies were found, of which 18 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis (see Figure 1).

Search strategyBetween September 2019 and March 2022, an exhaustive bibliographic search was carried out of published articles and doctoral theses on mindfulness-based interventions in educational contexts. The bibliographic databases consulted were PsycINFO, ERIC, Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar with the following keywords interconnected with the operator OR—“mindfulness”, “MBSR”, “MBCT”, “MBI”—combined by the operator AND with the words “education”, “student”, “classroom”, “school”, “child”, “teenager”, “young”, “adolescent”. A truncation character was added to retrieve modifications at the beginnings and ends of the terms. The search was performed for title, abstract, keywords and full text. Studies written in English or Spanish were included. Reference lists of previous studies and reviews (Dunning et al., 2019; Klingbeil et al., 2017; Maynard et al., 2017; Zenner et al., 2014; Zoogman et al., 2014) were reviewed for additional relevant studies, resulting in the inclusion of four additional studies. The studies found in the searches were stored, and duplicates were removed. The abstract of each article was then reviewed, and if appropriate for inclusion in the meta-analysis, the full article was evaluated. Two reviewers independently selected the 18 included studies. The degree of agreement calculated using Cohen’s kappa coefficient was κ = .98; disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer.

Data extractionA data extraction protocol was developed and applied in a systematic and standardized way to each of the studies included in the meta-analysis; the data recorded are as follows: (a) study identification (authors, year of publication, country, and journal name), (b) study design (numbers of participants in the intervention and control groups, intervention type, control group condition, number of measures, and follow-up time frame), (c) participants (age, female percentage, and educational level), (d) Intervention characteristics (number of weeks of training, number of minutes of each session, and whether the participants performed home practice), and (e) results (mean scores, standard deviations, and sample sizes). This process was carried out independently by two reviewers. Cohen's kappa coefficient was κ = .96 for the categorical variables, and the intraclass correlation (ICC) index for the quantitative variables grouped by domains was above .95 in all domains.

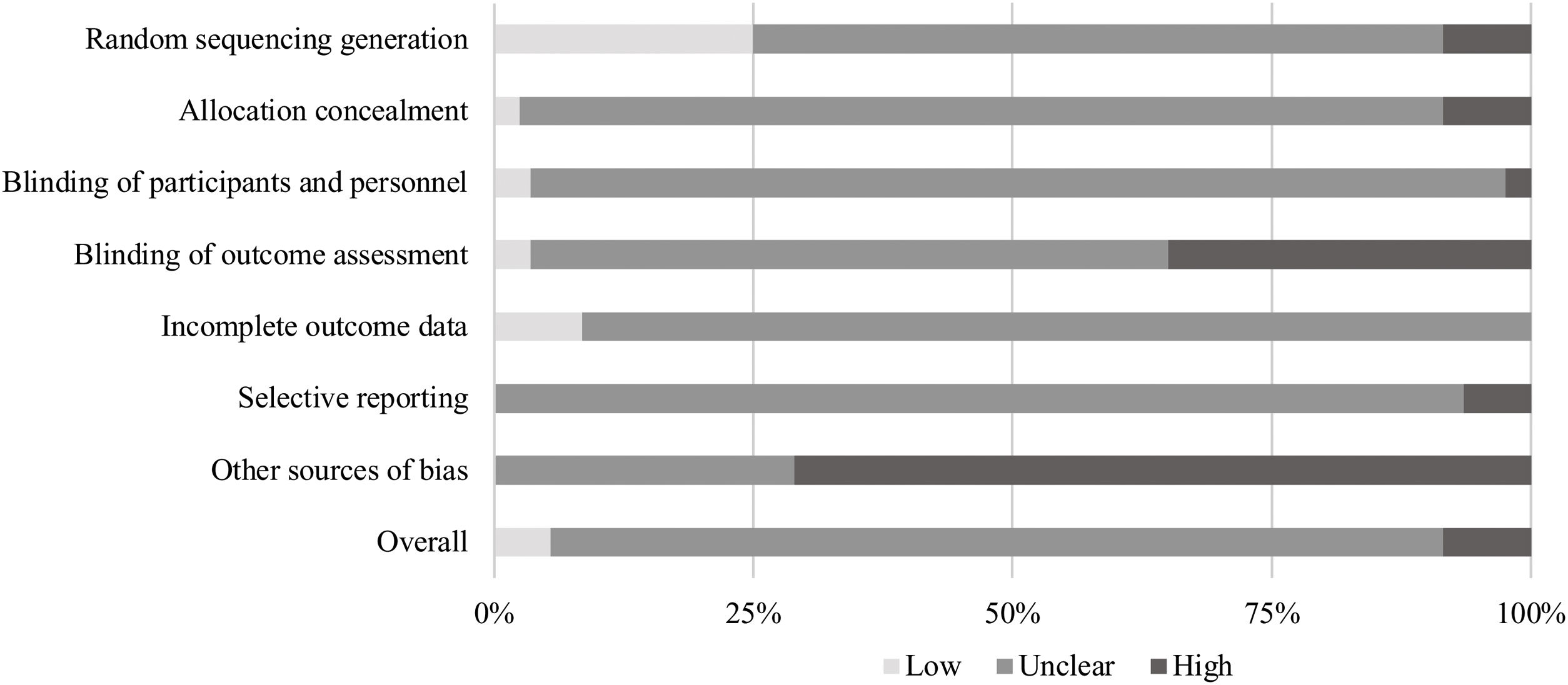

Risk of biasCochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing the risk of bias (Higgins et al., 2011) was used to assess the quality of the studies included in the meta-analysis. It was used with the 18 RCT studies to determine whether any biases influenced the true effect of the intervention. Two investigators assessed the risk of bias with the following categories: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, participants and personnel blinding, outcome assessment blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias. They were assessed with four classifications: “low risk”, “high risk”, “unclear risk” and “n/a”. Cohen’s Kappa coefficient resulted in κ = .96.

Calculation of effect sizeComprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 3 (CMA) software was used to calculate the effect size (Hedges’ g) and the standard error of the effect for all the studies included in the meta-analysis. To calculate the effect size (Hedges’ g) and standard error for the studies with more than one follow-up measure, to homogenize, the means and standard deviations were taken of the pre- and postmeasures of the experimental and control groups were taken. These values were obtained directly from the original studies, and the effect size was obtained from the difference in the standardized mean changes (Morris, 2008) corrected for the sample size (Botella & Sanchez-Meca, 2015).

Given the wide variety of factors measured by the scales used in the studies reviewed in the meta-analysis (see Table 1), the outcome measures analyzed were grouped into domains that have commonly been used to assess the effects of MBIs in other multioutcome meta-analyses (de Abreu Costa et al., 2019; Dunning et al., 2019; Zenner et al., 2014). Mindfulness skills included measures aimed at assessing perceived mindfulness. Mood states grouped measures of both positive and negative subjective emotional experience. Cognitive functions were assessed with both academic performance tests and peak performance tests and third-party assessment scales. Emotional intelligence included measures of attitudes and traits associated with emotion management. Emotional and behavioral adjustment grouped measures of behavioral problems linked to emotional arousal. The personal and social development category included measures of self-knowledge, self-esteem and social skills. To determine the direction of the effect, we considered whether the variable was positive or negative; in our meta-analysis, higher scores indicate a higher level in the dimension studied.

Grouped dependent variables

| Dimension | Variable | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Mindfulness skills | Mindfulness | 3 (100%) |

| Mood states | Emotional exhaustion | 2 (5.56%) |

| Anxiety | 8 (22.22%) | |

| Cholera | 1 (2.78%) | |

| Depression | 4 (11.11%) | |

| Positive energy | 1 (2.78%) | |

| Stress | 6 (16.67%) | |

| Avoidance | 4 (11.11%) | |

| Fatigue | 1 (2.78%) | |

| Anger/sadness | 1 (2.78%) | |

| Concern | 1 (2.78%) | |

| Relaxation | 1 (2.78%) | |

| Somatization | 2 (5.56%) | |

| Energy | 1 (2.78%) | |

| Transcendence | 1 (2.78%) | |

| Vigor | 2 (5.56%) | |

| Cognitive functions | Linguistic articulation | 1 (7.69%) |

| Attention | 1 (7.69%) | |

| Focused attention | 1 (7.69%) | |

| Sustained attention | 1 (7.69%) | |

| Processing speed and quality | 1 (7.69%) | |

| Selective attention and processing speed | 1 (7.69%) | |

| Language comprehension | 1 (7.69%) | |

| Attention deficits | 2 (15.38%) | |

| Writing | 1 (7.69%) | |

| Spatial structuring | 1 (7.69%) | |

| Mental flexibility | 1 (7.69%) | |

| Verbal flexibility | 1 (7.69%) | |

| Verbal fluency | 2 (8.70%) | |

| Motor skills | 1 (4.35%) | |

| Memory icons | 1 (4.35%) | |

| Reading | 1 (4.35%) | |

| Expressive language | 1 (4.35%) | |

| Immediate auditory–verbal memory | 1 (4.35%) | |

| Working memory | 1 (4.35%) | |

| Verbal originality | 1 (4.35%) | |

| Visual perception | 1 (4.35%) | |

| Learning disabilities | 2 (8.70%) | |

| Academic performance | 10 (43.48%) | |

| Rhythm | 1 (4.35%) | |

| Emotional intelligence | Prejudicial attitude | 5 (26.32%) |

| Emotional care | 2 (10.53%) | |

| Emotional clarity | 2 (10.53%) | |

| Perceived discrimination | 1 (5.26%) | |

| Empathy | 5 (26.32%) | |

| Cognitive reassessment | 1 (5.26%) | |

| Emotional repair | 2 (10.53%) | |

| Emotional suppression | 1 (5.26%) | |

| Emotional and behavioral adjustment | Aggressiveness | 3 (16.67%) |

| Violent behavior | 1 (5.56%) | |

| Atypical behavior | 1 (5.56%) | |

| Disruptive behavior | 1 (5.56%) | |

| Hyperactivity | 2 (11.11%) | |

| Attention–Hyperactivity | 1 (5.56%) | |

| Hostility | 1 (5.56%) | |

| Impulsivity | 4 (22.22%) | |

| Inattention/Passivity | 1 (5.56%) | |

| Anger | 1 (5.56%) | |

| Behavioral problems | 2 (11.11%) | |

| Personal and social development | Absorption | 1 (3.70%) |

| Adaptability | 1 (3.70%) | |

| Self-concept | 14 (51.85%) | |

| Self-efficacy | 2 (7.41%) | |

| Self-esteem | 1 (3.70%) | |

| Cynicism | 1 (3.70%) | |

| Dedication | 1 (3.70%) | |

| Leadership skills | 1 (3.70%) | |

| Social skills | 1 (3.70%) | |

| Coping capacity, operability and realization | 4 (14.82%) |

The analyses of the meta-analysis were performed using the metafor package of the R statistical program (Viechtbauer, 2010) together with the R Studio program. A three-level random-effects meta-analysis model was used to pool the effect sizes and examine the overall efficacy of the mindfulness-based interventions and the efficacy for each of the dimensions analyzed. A three-level meta-analysis was applied, which is an extension of the random-effects model, because it allows us to extract the effect sizes for each primary study achieving maximum statistical power by modeling (level one) the sampling variation for each effect size, (level two) the variation over outcomes within a study, and (level three) the variation over studies (Assink & Wibbelink, 2016; Van den Noortgate et al., 2015).

Heterogeneity, the diversity in the characteristics of the outcome measures, is quantified by estimating random effects variances for each level of our model; level three shows the variance in between-study heterogeneity, and level two shows the variance in within-study heterogeneity (Cheung, 2014).

Meta-regressions with a three-level mixed-effects model were used to evaluate the impact of eight moderating variables included in the research: intervention type, control group type, educational level, home practice, age, percentage of women participants, session duration in minutes, and intervention duration in weeks. Regarding the analysis of the moderating variables, the three-level adjusted meta-regression procedure for continuous variables and variables with two or more categories described by Assink and Wibbelink (2016) was used using the R package metafor.

Publication bias was assessed through two methods in its version adapted for three-level meta-analyses (Fernández-Castilla et al., 2021; Rothstein et al., 2005; Rubio-Aparicio et al., 2018). First, the Egger regression test was performed, which is based on a simple linear regression model; if Z ≥ 1.96 or ≤-1.96, the effect is significant. Second, the Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation test was employed based on correlating the standardized magnitude of the effect and its variance using Kendall's Tau as a measure of association, and the absence of statistical significance suggests that there is no publication bias.

ResultsDescriptive characteristics of the studiesThe studies included in the meta-analysis were published between 2009 and 2021 (see Table 2). The mean sample size of the primary studies was 81.72 (66.76), with a minimum sample size of 27 and a maximum sample size of 320. The total sample consisted of 1471 participants, with a mean percentage of 57.27% female (35.48%–88.68%). The age range was from 4 to 49 years, with a mean age of 15.62 (5.52). Of the total number of participants, 20.60% were studying at university and 19.37% were enrolled in high school; 39.02%, in compulsory secondary education; 8.23%, in primary education; and 12.78%, in early childhood education. The control group types were control group without intervention (33.33%), waiting list with intervention after study completion (61.11%) and the INTEMO program1 (5.56%). The following techniques were used in the interventions: flow meditation (55.56%), MBCT (11.11%), and other MBIs (33.33%). The average durations were 10.33 (5.14) weeks and 56.67 (34.40) minutes per session. In all 18 studies, pretest and posttest measures were taken, while in four of them, in addition to these measures, data were collected several months after the intervention (follow up).

Details of the studies included in the systematic review

| Authors | Educational level | % Female | Age | Group experimental | Group control | Duration | Practice at home | Measures | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amutio-Kareaga et al. (2015) | High school | 51 | 17.05 (.78) | Meditation | Waiting list | Weeks = 8 | Yes | 2 | ?? ? ? ? ? + |

| R = 16-19 | n = 21 | n = 22 | Session (min) = 120 | ||||||

| Baena-Extremera et al. (2021) | Primary and Secondary education | 13.06 (.54) | MBI | Control | Weeks = 6 | Yes | 2 | -? ? +? ? ? | |

| R = 10-16 | n = 156 | n = 164 | Session (min) = 10 | ||||||

| Cobos-Sánchez et al. (2019) | Secondary education | 45.80 | 12 (.78) | MBI | INTEMO | Weeks = 5 | No | 2 | ?? ? ? -? + |

| R = 12-15 | n = 57 | n = 63 | Session (min) = 60 | ||||||

| De la Fuente et al. (2010) | University | 86.84 | 24.36 (4.72) | Meditation | Waiting list | Weeks = 10 | Yes | 3 | ?? ? ? ? ? ? |

| R = 18-19 | n = 19 | n = 19 | Session (min) = 90 | ||||||

| Franco (2009) | High school | 71.70 | 17.25 | Meditation | Waiting list | Weeks = 10 | Yes | 3 | ?? - -? ? + |

| R = 15-18 | n = 30 | n = 30 | Session (min) = 90 | ||||||

| Franco et al. (2010) | High school | 51 | 16.45 (.78) | Meditation | Waiting list | Weeks = 10 | Yes | 2 | ?? ? ? ? ? + |

| R = 16-18 | n = 24 | n = 25 | Session (min) = 90 | ||||||

| Franco, de la Fuente et al. (2011) | High school | 72.62 | 17.06 (2.44) | Meditation | Waiting list | Weeks = 10 | Yes | 2 | ?? ? ? ? ? + |

| R = 16-19 | n = 42 | n = 42 | Session (min) = 90 | ||||||

| Franco, Mañas et al. (2011) | Secondary education | 47.54 | 16.75 (.83) | Meditation | Waiting list | Weeks = 10 | Yes | 2 | ?? ? ? ? ? + |

| R = 16-18 | n = 31 | n = 30 | Session (min) = 90 | ||||||

| Franco, Molina et al. (2011) | University | 88.68 | 26.78 (5.96) | Meditation | Waiting list | Weeks = 10 | Yes | 2 | ?? ? ? ? ? + |

| R = 19-34 | n = 26 | n = 27 | Session (min) = 90 | ||||||

| Franco et al. (2016) | Secondary education | 41 | 15.85 (2.38) | Meditation | Waiting list | Weeks = 10 | Yes | 2 | ?? ? ? ? ? + |

| R = 12-19 | n = 13 | n = 14 | Session (min) = 15 | ||||||

| Gallego et al. (2014) | University | 57.60 | 20.07 (3.68) | MBCT | Control | Weeks = 8 | Yes | 2 | ?? ? ? ? ? + |

| R = 18-43 | n = 41 | n = 42 | Session (min) = 60 | ||||||

| Gallego et al. (2016) | University | 54.60 | 20.33 (1.55) | MBCT | Control | Weeks = 8 | Yes | 2 | + +? ? ? ? + |

| R = 18-49 | n = 84 | n = 45 | Session (min) = 30 | ||||||

| García-Rubio et al. (2016) | Primary education | 35.48 | 11.17 (.36) | MBI | Control | Weeks = 6 | No | 2 | - - +? ? ? + |

| n = 16 | n = 15 | Session (min) = 50 | |||||||

| López-Rodríguez et al. (2012) | Secondary education | 65.22 | 16.80 (1.04) | Meditation | Control | Weeks = 11 | Yes | 3 | ?? ? ? ? ? ? |

| R = 15-18 | n = 23 | n = 23 | Session (min) = 60 | ||||||

| Moreno-Gómez & Cejudo (2019) | Early childhood education | 52.70 | 5.08 (. 37) | MBI | Waiting list | Weeks = 24 | No | 3 | ?? ? +? ? + |

| R = 4-6 | n = 48 | n = 26 | Session (min) = 15 | ||||||

| Moreno-Gómez et al. (2020) | Early childhood education | 55.20 | 5.69 (.37) | MBI | Control | Weeks = 24 | No | 2 | ?? ? +? ? + |

| R = 5-6 | n = 76 | n = 38 | Session (min) = 15 | ||||||

| Ricarte et al. (2015) | Primary education | 45.56 | 8.90 (1.98) | MBI | Waiting list | Weeks = 6 | No | 2 | ?? ? ? ? + + |

| R = 6-13 | n = 45 | n = 45 | Session (min) = 15 | ||||||

| Soriano & Franco (2010) | High school | 51 | 16.45 (.78) | Meditation | Waiting list | Weeks = 10 | Yes | 2 | ?? ? ? ? ? + |

| R = 16-18 | n = 24 | n = 25 | Session (min) = 30 |

Notes. For risk of bias, - = low risk of bias, + = high risk of bias,? = unclear risk of bias on the following indices: random sequencing generation, allocation concealment, participant and personnel blinding, outcome assessment blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias.

The risk of bias is low in 25% of studies for random sequencing generation; 2.5% for allocation concealment; 3.5% for participant and personnel blinding, and outcome assessment blinding; 8.5% for incomplete outcome data; and 0% for selective reporting and other sources of bias. The risk of bias is high in 8.5% of studies for random sequencing and allocation concealment; 2.5% for participant and personnel blinding; 35% for outcome assessment blinding; 0% for incomplete outcome data; 6.5% for selective reporting; and 71% for other sources of bias. In the other cases, the risk of bias was unclear (see Figure 2). See Table 2 for the individual studies.

Effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventionsEighteen RCT studies were analyzed, with three intervention types and three control group types, 144 measures and six dependent variables. The average overall effect size was g = 0.62; 95% CI [0.43, 0.80], p < .0001. Therefore, the effect size estimation showed that mindfulness-based interventions were effective for the studied variables with a medium effect size. Heterogeneity was found between studies (τ2Level 3 = .13, p < .0001) and within studies (τ2Level 2 = .09, p < .0001). The likelihood ratio test demonstrates that the three-level model provided a significantly better fit compared to the two-level model with restricted level three heterogeneity (χ12 = 51.75, p < .0001). Of the total variances, 18.28%, 33.27% and 48.45% were distributed in levels one, two and three, respectively. Egger’s regression test (Z = 14.49, p < .0001) and Begg and Mazumdar’s correlation test (Kendall’s tau = -0.24, p < .0001) were used to assess publication bias. Statistically significant effect sizes were obtained for all dimensions, with the exception of the mindfulness skills dimension (see Table 3). Heterogeneity between and within studies was statistically significant for all the dimensions analyzed.

Meta-analyses performed with the following dependent variables

| Dependent variables | k | ES | g (95% CI) | τ2Level2 | τ2Level3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal and social development | 7 | 27 | 0.84 (0.48, 1.20)*** | .21*** | .11*** |

| Mood states | 10 | 36 | 0.44 (0.29, 0.59)*** | . 10*** | .01*** |

| Cognitive functions | 8 | 41 | 0.67 (0.29, 1.05)** | . 02*** | .25*** |

| Emotional intelligence | 4 | 19 | 0.61 (0.16, 1.07)* | . 23*** | .12*** |

| Emotional and behavioral adjustment | 5 | 18 | 0.54 (0.06, 1.02)* | . 22** | .00** |

| Mindfulness skills | 3 | 3 | 0.51 (-1.47, 2.49) | . 27*** | .27*** |

Notes. k = number of studies; ES = number of effect sizes; g = mean effect size; CI = confidence interval; τ2Level 2 = within-study variance; τ2Level 3 = between-study variance.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Table 4 shows the moderating variables that predict variations in the overall average effect sizes.

Simple meta-regressions with moderating variables for the overall average efficacy of MBIs

| Moderating variables | k | ES | B0/g (95% CI) | B1 (95% CI) | F (df1, df2)a | pb | τ2Level2 | τ2Level3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention typec | 48.47 (3, 141) | <.0001 | .09*** | .03*** | ||||

| MBCT | 2 | 6 | 0.44 (0.05, 0.83)* | |||||

| MBIs | 6 | 66 | 0.25 (0.07, 0.42)** | |||||

| Meditation | 10 | 72 | 0.89 (0.74, 1.04)*** | |||||

| Control typec | 22.95 (3, 141) | <.0001 | .09*** | .09*** | ||||

| Control | 6 | 36 | 0.34 (0.07, 0.62)* | |||||

| Waiting list | 11 | 101 | 0.80 (0.60, 1.00)*** | |||||

| INTEMO | 1 | 7 | .17 (-0.48, 0.81) | |||||

| Educational level c | 35.77 (5, 139) | <.0001 | .09*** | .02*** | ||||

| Early childhood education | 2 | 33 | 0.21 (-0.05, 0.46) | |||||

| Primary education | 2 | 16 | 0.25 (-0.05, 0.55) | |||||

| Secondary education | 5 | 39 | 0.50 (0.31, 0.68)*** | |||||

| High school | 5 | 34 | 1.13 (0.93, 1.33)*** | |||||

| University | 4 | 22 | 0.57 (0.34, 0.80)*** | |||||

| Home internshipsc | 18 | 144 | 0.21 (-0.03, 0.45) | 0.57 (0.28, 0.86)*** | 15.25 (1, 142) | <.0001 | .09*** | .06*** |

| Aged | 18 | 144 | 0.11 (-0.36, 0.58) | 0.03 (0.00, 0.06)* | 5.13 (1, 142) | .03 | .09*** | .10*** |

| Duration in minutesd | 18 | 144 | 0.09 (-0.16, 0.33) | 0.01 (0.01, 0.01)*** | 23.30 (1, 142) | <.0001 | .09*** | .04*** |

| Duration in weeksd | 18 | 144 | 0.76 (0.35, 1.17)*** | -0.01 (-0.05, 0.02) | .58 (1, 142) | .45 | .09*** | .14*** |

| Percentage of womend | 17 | 134 | 0.11 (-0.66, 0.87) | 0.01 (-0.00, 0.02) | 1.97 (1, 132) | .16 | .10*** | .13*** |

Notes. k = number of studies; ES = number of effect sizes; B0/g = intercept/mean effect size; B1 = estimated regression coefficient; CI = confidence interval; F = omnibus test of model regression coefficients; df = degrees of freedom; τ2Level 2 = within-study variance; τ2Level 3 = between-study variance.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

a Omnibus test of the regression coefficients of the model.

bp omnibus test value.

c Categorical moderating variables.

d Continuous moderating variables.

All the intervention types had a statistically significant influence on efficacy; however, the effect size was larger of the flow meditation intervention. Regarding the control group types, control without intervention and waiting list had a statistically significant influence on efficacy, while the INTEMO program control group was statistically nonsignificant. Statistically significant results were found for the influence of age on the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions. The educational levels secondary education, high school and university had positive and statistically significant effects, while for early childhood and primary education, no statistically significant results were found. The performance of mindfulness practices at home had a positive and statistically significant influence on the efficacy of the interventions. Duration in minutes also moderated the intervention efficacy, but no statistically significant results were found for duration in weeks or for the percentage of female participants.

DiscussionMindfulness-based techniques have been frequently employed in the clinical setting as a stress-coping strategy (Kabat-Zinn, 1982, 2003). However, they have also been employed in different educational stages from early childhood education to university (Felver et al., 2016). Although some previous meta-analytic reviews have been conducted of the effect of these mindfulness-based educational programs, until now, the effectiveness of the programs carried out in the Spanish educational context has not been evaluated. Our results show that MBIs are effective with a medium overall effect size (Cohen, 1988). MBIs are found to have a positive effect on most of the dimensions analyzed. These results are congruent with studies from other countries that support the positive effects of school-based MBIs in increasing self-esteem and social competence (Klingbeil et al., 2017; Waters et al., 2015). Furthermore, coinciding with other international studies, our results show that MBIs are effective in improving mood at school (Dunning et al., 2019; Zenner et al., 2014) and produce positive effects on cognitive functions and academic performance (Dunning et al., 2019; Klingbeil et al., 2017; Maynard et al., 2017; Zenner et al., 2014). The MBIs analyzed also positively influence emotional intelligence skills (Maynard et al., 2017) and behavioral regulation (Dunning et al., 2019; Klingbeil et al., 2017; Zoogman et al., 2014).

However, for the mindfulness skills dimension, we find a positive but not significant mean effect. Dunning et al. (2019) and Klingbeil et al. (2017) find significant positive effects of school-based MBIs on increasing mindfulness, albeit with small effect sizes. According to Dunning et al. (2019), the effect of MBIs on mindfulness measures may be biased due to the type of control group; they also find, as in our meta-analysis, that MBIs have larger effect sizes when is compared with waitlists than with all other types of control groups. In our study, the lack of significance of the MBI efficacy for the mindfulness skills dimension can be justified because it was analyzed in only three of the interventions evaluated, one of them using the INTEMO program as a control group. In the study by Cobos-Sánchez et al. (2019), the mindfulness dimension improves more with the INTEMO program than it does with the mindfulness intervention. A proposal for future research is to analyze the effectiveness of emotional intelligence education programs combined with mindfulness programs.

Regarding the other moderating variables, such as the intervention type, the results show that all the intervention types are effective, although the flow meditation intervention has a greater influence. This may be because most of the studies included in the meta-analysis implemented the flow meditation intervention. On the other hand, the influence of the moderating variable age on the efficacy of the interventions is significant, but with a low effect size; that is, MBIs are slightly more effective among older participants. Previously, Zoogman et al. (2014) conclude that age does not significantly moderate the efficacy of MBIs. However, recently, and akin to our results, Dunning et al. (2019) find that age is a significant moderator of improvements in executive functions and the reduction of negative behaviors.

In a result that is closely related to age, we found that the interventions are effective for the educational levels high school, university and secondary education, in that order. It is very suggestive that the highest levels of efficacy are found in high school, which may be due to the high level of stress generated by the university entrance exams and by the changes of late adolescence. In addition, performing mindfulness practices at home during the program implementation and the session duration in minutes significantly influence the efficacy of the interventions. These findings can be compared with those of Waters et al. (2015), who conclude that the characteristics of each program, such as practice duration and frequency, influence the results. However, as found by Zoogman et al. (2014), neither the influence of intervention duration in weeks nor that of the percentage of participating women is significant.

Among the limitations of our study, the high heterogeneity observed when assessing the effect sizes stands out. This heterogeneity is mainly due to the large number of measures used in the studies, which justified the use of a three-level meta-analysis model. Additionally, a meta-analysis was performed with various mindfulness-based interventions and populations, socioeconomic levels and geographical scopes, so caution is necessary when generalizing the results (Burke, 2010; Felver et al., 2016; Langer et al., 2015). In addition, a high risk of publication bias was observed, which can be explained by the tendency to publish studies with significant results (Thornton & Lee, 2000). At the same time, there is an assessment bias due to the diversity of measurement instruments used in the studies analyzed as well as the fact that only RCT studies were included in the meta-analysis. However, in the review of the results of the MBI studies excluded because they were not RCTs, similar effects were observed as those obtained in this meta-analysis. For example, a recent nonrandomized study on the results of an MBI in the Spanish educational context in the fifth and sixth grade of primary school shows significant improvements in executive functions, although no significant changes are observed in stress levels or behavioral problems (Folch et al., 2021). Future studies evaluating MBIs should use measures similar to those used in previous studies to achieve greater homogeneity in the results and standardized formats that allow the replication and comparison of studies to provide a solid research basis.

ConclusionsThe findings support the implementation of mindfulness-based programs in Spanish schools, as such programs can be beneficial for students in their personal development and well-being as well as in their academic performance and social relationships. The present study is useful for the development of future programs based on mindfulness as it aids in the understanding of the characteristics that make them more effective in the educational setting. The use of MBIs in the classroom should involve practice at home, and they will be more effective when they are performed in sessions of longer durations and with students who are older. On the other hand, the lack of significant effects in early childhood and primary education suggests that it is necessary to adapt the MBIs specifically for these educational stages.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that the research was conducted in the absence of financial and personal relationships that could be considered potential conflicts of interest.

Financing sourcesThis research work did not receive any specific financial support from public, private or nonprofit institutions.

We acknowledge the work of the authors of the studies included in the meta-analysis and the schools, families and students who participated in their research.

Funding for open access publishing: Universidad Pablo de Olavide/CBUA.

*Indicates inclusion in meta-analysis.

Please cite this article as: Arenilla Villalba MJ, Alarcón Rubio D, Povedano Díaz MA. Meta-análisis multinivel de los programas escolares de intervención basados en mindfulness en España. Revista de Psicodidáctica. 2022;27:109–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psicod.2022.04.005

INTEMO is an emotional education program for adolescents, based on the theoretical model of Salovey and Mayer (1990).