Chronic urticaria can be the initial clinical presentation of a number of different diseases. The objective of the present study was to report the associated diseases during a ten-year clinical-laboratory follow-up in patients with an initial diagnosis of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) of unknown cause.

MethodsA prospective, longitudinal cohort study with a ten-year clinical-laboratory follow-up was conducted. Patients with a history of urticarial plaques of over six weeks presenting as the only clinical symptom were selected. Individuals with other clinical conditions, urticaria of known causes or chronic physical urticaria were excluded. The following tests were initially performed: haemogram, urine type I, stool parasite exam and sedimentation rate. The following exams were ordered during follow-up: PPD; urine culture; serology tests; antithyroid and antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, lupus anticoagulant; thyroid hormones; serum immunoglobulin; paranasal sinus and thorax radiographs; testing for BK and Helicobacter pylori; and prick tests.

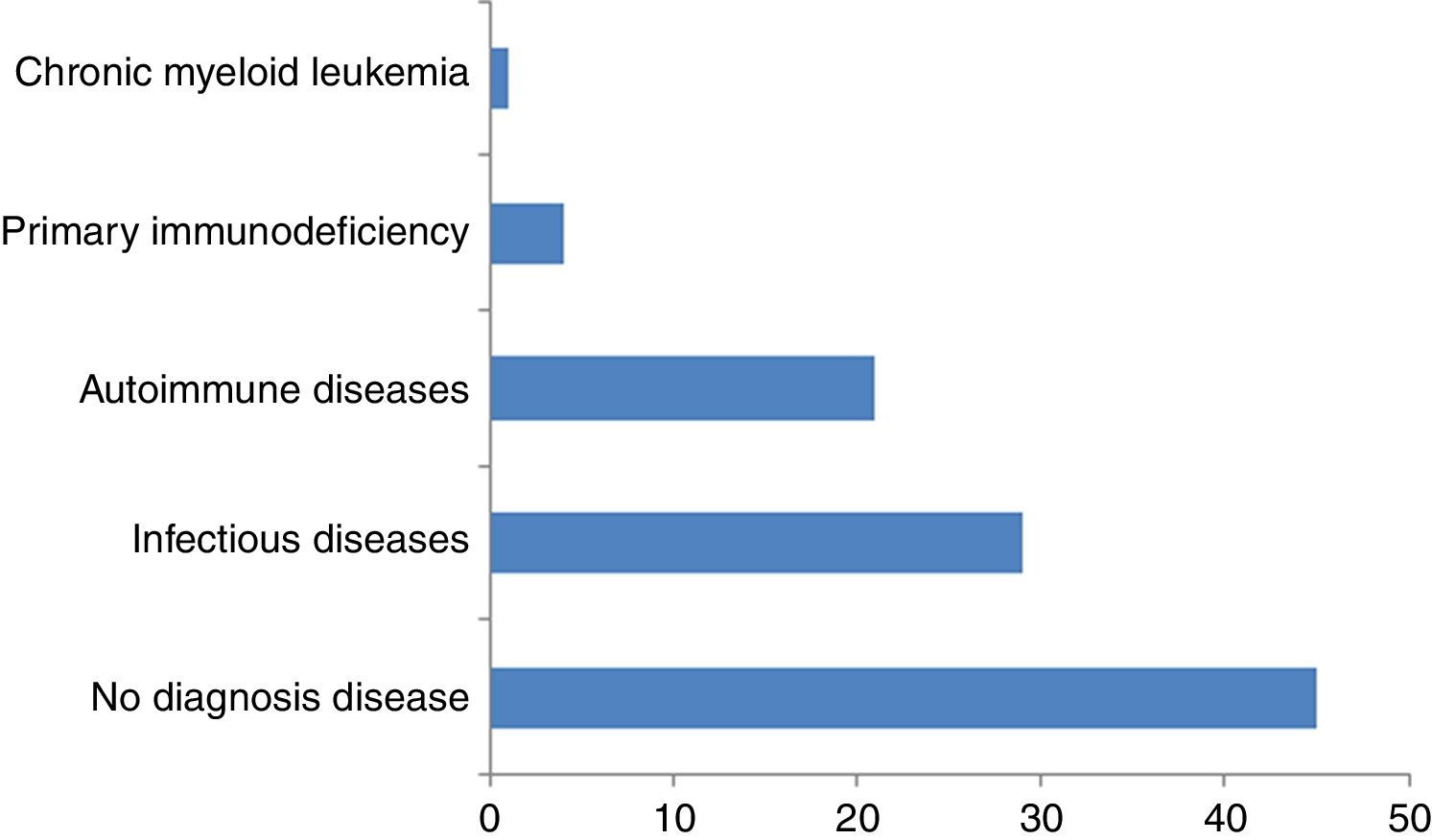

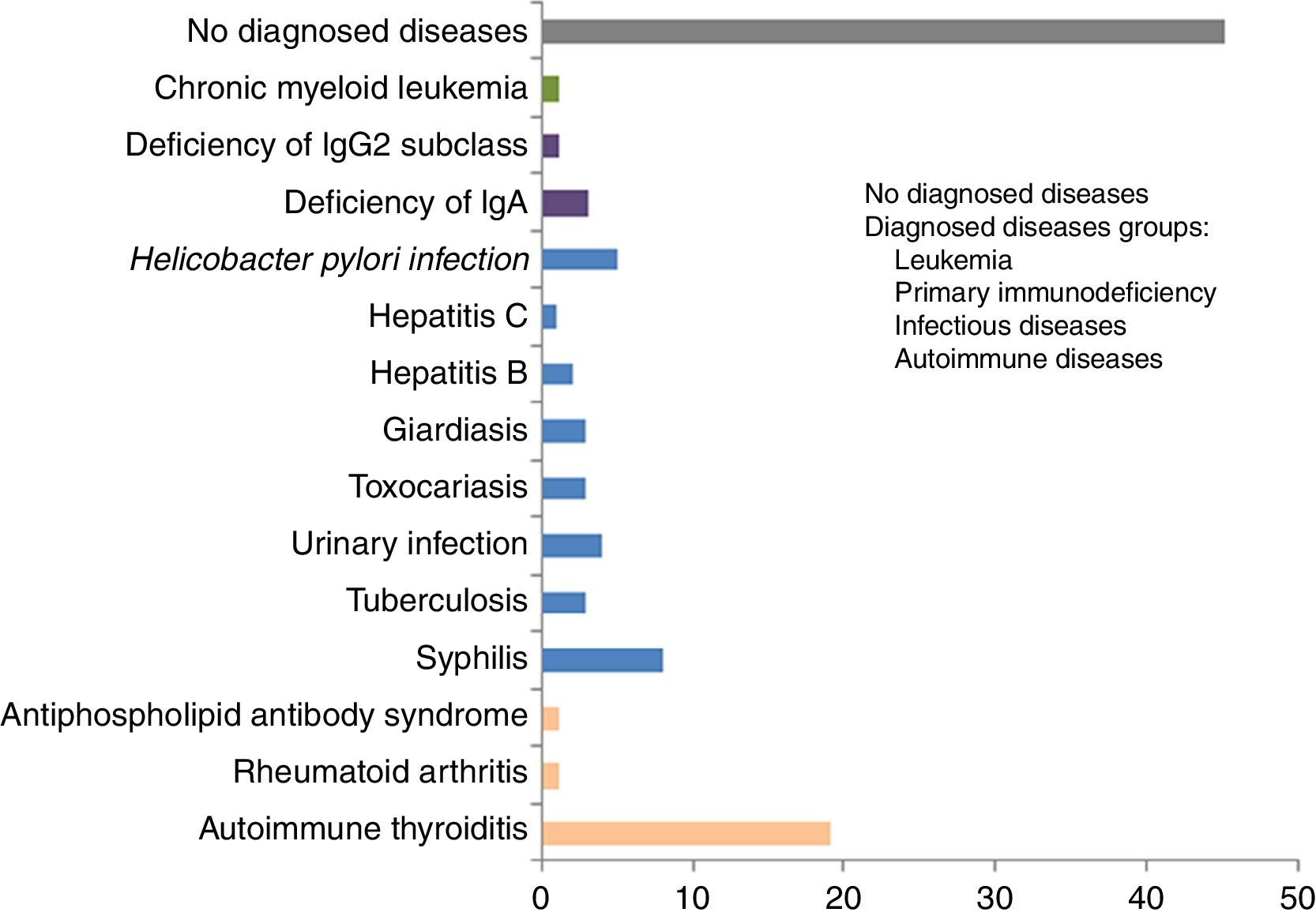

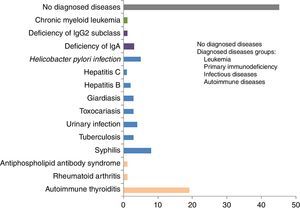

ResultsInfections were diagnosed in 29% of patients (syphilis, parasitosis, H. pylori, urinary infection, tuberculosis, hepatitis B and C); autoimmune diseases in 21% (thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome); primary immunodeficiencies in 4% (IgA and IgG2 deficiencies); and chronic myeloid leukaemia in 1%. At ten-years of follow-up, the urticaria diagnosis was CSU of unknown cause in 45% of the cases.

ConclusionThis ten-year clinical-laboratory follow-up of 100 individuals with chronic urticaria as the initial diagnosis revealed the presence of associated diseases in over half of the cases. The most prevalent diseases were infections and autoimmune diseases besides primary immunodeficiencies and blood diseases.

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is an inflammation of the skin characterised by pruritic, evanescent, erythematous-oedematous plaques and papules (wheals) that are continuous or intermittent, daily or almost daily, with or without angioedema, persisting for at least six weeks.1–3 The condition affects 0.1–5% of the general population, typically during the third and fourth decades of life, with a predominance in females.1,4 CSU negatively impacts quality of life, affecting daily activities as well as sleep. It can lead to emotional disorders and social isolation, besides having a high economic burden on healthcare systems.1,3,4

Urticaria can be the initial clinical presentation of other diseases, often preceding the onset of their respective characteristic signs and symptoms. CSU is defined as having a known cause when associated with infections, neoplasias or immunodeficiencies, and unknown cause in the remaining cases; autoimmune diseases are among the differential diagnoses of CSU.1 Follow-up of CSU patients should be considered, potentially allowing the identification or evolution of a number of diseases or situations, even though the cause may remain unidentified in many cases.2

Currently, few prospective longitudinal cohort studies involving long-term clinical-laboratory follow-up of CSU are available in the literature. Diagnosing the causes of CSU is important to allow specific treatment to be given.

These factors prompted the present study whose objective was to report associated diseases during a ten-year clinical-laboratory follow-up in patients with an initial diagnosis of chronic spontaneous urticaria of unknown cause.

Materials and methodsThe Research Ethics Committee of the Institution, under protocol no. 239/08, approved the study. All participants signed the informed consent form.

A ten-year prospective, longitudinal, cohort study was conducted involving clinical-laboratory follow-up of 100 patients with a history of urticaria plaques of over six weeks presenting as the only clinical symptom and no signs or symptoms suggestive of other diseases. The patients were referred from different services to the specialised sector of a tertiary hospital situated in a large metropolis.

Inclusion criteria were: patients of both sexes, different ages, having a history of urticaria of over six weeks, presenting as the only clinical symptom at the beginning of follow-up, and having an unknown cause. Exclusion criteria were: acute spontaneous urticaria, chronic spontaneous urticaria of known cause, physical urticaria (factitious, related to delayed pressure, induced by cold, heat, sun or vibration), other types of urticaria (aquagenic, cholinergic, contact, induced by exercise), autoimmune diseases, urticaria or angioedema secondary to the use of medications, and patients initially presenting with associated clinical conditions concomitant to urticaria. The first 100 patients seen consecutively at the sector meeting the defined inclusion criteria were selected for the study.

The following tests were first performed: haemogram, urine type I, stool parasite exam and sedimentation rate (ESR). The other complementary exams were ordered during the follow-up period according to evolution, when patients presented new signs and/or symptoms or provided additional information not hitherto reported. The following exams were performed: intradermal injection of purified protein derivative of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (PPD); serology tests for HIV, Hepatites B and C, Treponema pallidum, Epstein-Barr virus, Cytomegalovirus and Toxocara cannis; chest and paranasal sinus radiographs; urine culture in the presence of leukocyturia on urine type 1 exam (patients with leukocyturia and negative urine culture were excluded); testing for Koch's Bacillus (BK) and sputum cultures in individuals with strong PPD reactor; thyroid hormones (free T4 and TSH), antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and rheumatoid factor (RF) in suspected autoimmune diseases; lupus anticoagulant in cases with history of thromboembolism prior to urticaria onset; prick tests for aeroallergens and foods in allergic rhinitis or suspected food allergy; Helicobacter pylori testing in patients previously reporting dyspeptic symptoms; levels of sera immunoglobulin classes and of IgG subclasses in cases of repetitive infections; myelogram in the presence of pancytopenia. Individuals with high ESR and no abnormalities on other laboratory exams or other clinical conditions were followed as patients with CSU of unknown cause. At the beginning of follow-up, all patients were questioned and reported absence of arthralgia, dysuria or dyspeptic symptoms. Skin biopsies were not performed since the lesions had characteristics of true wheals.

ResultsOf the 100 individuals followed, 73 were female and 27 male; patients had a median age of 33 years and mean age of 44 years. Among the total patients studied, 36 had angioedema associated with urticaria, 9 of which were diagnosed as having associated diseases during follow-up (eight autoimmune thryroiditis and one IgG subclass deficiency) and 27 remained with the diagnosis of CSU of unknown cause. None of the patients had angioedema alone. Age at urticaria onset in the patients studied was, on average, between the second and third decades of life. Duration of urticaria symptoms prior to commencement of the study follow-up ranged from two to ten years. Mean duration of the observational period ranged from three months (chronic myeloid leukaemia) to ten years.

All of the patients were followed throughout the ten-year study period. Urine culture was ordered for patients with leukocyturia detected on the urine type 1 exam. Those patients with urinary infection (positive urine culture) were given specific treatment, with resolution of urticaria after two months of this treatment. Chemotherapy successfully controlled the chronic myeloid leukaemia. Individuals diagnosed with associated diseases concomitant to urticaria who improved after specific treatment (urinary infection, parasitises, hepatitis C, chronic myeloid leukaemia and some cases of infection with H. pylori) required anti-histamines until administration of the specific therapy. Patients without resolution of urticaria after specific treatment for the associated disease diagnosed (hepatitis B, rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases), and likewise patients with CSU of unknown cause, remained with urticaria, requiring anti-histamines for symptom control.

Skin tests for aeroallergens were positive in 25 patients, and the test correlated with allergic rhinitis in 11, but not with urticaria. All the skin tests for foods were negative, confirmed by the absence of exacerbation or triggering of urticaria after consumption of the suspected food.

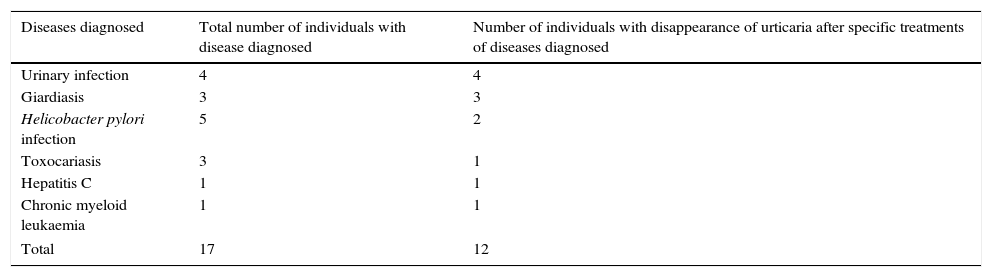

The number of individuals with disappearance of urticaria after treatment of the associated disease diagnosed is shown in Table 1. The groups of diseases and individual diseases diagnosed during the study are depicted in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively.

Number of individuals with disappearance of urticaria after specific treatments of diseases diagnosed during ten-year follow-up, among 100 individuals with an initial diagnosis of chronic spontaneous urticaria of unknown cause.

| Diseases diagnosed | Total number of individuals with disease diagnosed | Number of individuals with disappearance of urticaria after specific treatments of diseases diagnosed |

|---|---|---|

| Urinary infection | 4 | 4 |

| Giardiasis | 3 | 3 |

| Helicobacter pylori infection | 5 | 2 |

| Toxocariasis | 3 | 1 |

| Hepatitis C | 1 | 1 |

| Chronic myeloid leukaemia | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 17 | 12 |

The main associated diseases diagnosed during the follow-up of the CSU patients were, in descending order of frequency: syphilis, infections by parasites and protozoa (giardiasis, toxocariasis), H. pylori, urinary infection, tuberculosis, and hepatitis B and C. The association between infections and urticaria can be considered more direct in cases where the urticaria disappeared after treatment of the infection, as was observed in the urinary infections, parasitosis, hepatitis C and, in some cases of H. pylori infection.

Infectious and parasitic diseases have previously been associated with CSU, varying by population and geographic region.2,5,6 In the present study, urticaria disappeared in most of the patients with parasitosis after specific treatment for the parasite. An association between CSU and Giardia lamblia, Strongyloides stercoralis, Blastocystis hominis and T. cannis has also been reported,4,5,7 with disappearance of urticaria after anti-parasitic treatment.1,8 The resolution of urticaria after treatment of the urinary infection suggests an association between urticaria and this infection. Reports in the literature cite the disappearance of CSU following treatment of urinary infections.6 In the present study, CSU disappeared after treatment for infection by H. pylori in two patients whereas three others showed no change in the condition. The role of H. pylori in CSU remains unclear,1,2,9–11 with descriptions of improvement in urticaria by some authors while others observed no changes after treating the infection.10–12 The patient with hepatitis C was treated using ribavirin and interferon, exhibiting resolution of urticaria after six months of negative viral load. There are few reports in the literature of CSU as the only presentation of infection by the hepatitis C virus, with disappearance of urticaria in some patients after HCV treatment.1,13,14 However, few reports exist of the disappearance of CSU after treatment of hepatitis B,6,12 which is more commonly associated with acute urticaria. Urticaria did not disappear after specific therapy in patients diagnosed with tuberculosis. Few reports exist in the literature of tuberculosis in CSU.6 Syphilis was the most frequent infectious disease found in the CSU patients studied, possibly owing to the high incidence of the disease in Brazil (around 937,000cases/year). Despite the number of patients with syphilis, urticaria disappeared in none of these individuals following treatment for syphilis. The association between syphilis and CSU has seldom been described, where syphilis has been more commonly associated with cold-induced urticaria.6

The most frequently diagnosed autoimmune diseases in the present study were autoimmune thyroiditis, followed by rheumatoid arthritis, and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Given the theory regarding autoimmune disease, specific antibody tests (ANA, RF, antithyroid antibodies) were carried out as opposed to autologous serum tests, owing to the latter's variable accuracy, moderate specificity, and likelihood of contamination, despite being practical to perform.15

The patients with autoimmune thyroiditis were euthyroid and had not received hormone replacement therapy. Urticaria persisted in all of these patients and was controlled using anti-histamines. Studies report that 6.5%-57% of CSU cases evolve to thyroid diseases such as Hashimoto's thyroiditis and Graves’ disease, particularly among women.15–18 A prevalence of at least one anti-thyroid antibody has been described in 20% of CSU patients,15,16 and was associated with more severe and prolonged progression of urticaria.16–18 The autoantibodies can activate the classic pathway of the complement or exhibit crossed reactivity with specific IgE, having a similar affinity in mastocyte receptors.19 Hormone replacement in euthyroid patients exhibiting elevated antibodies is controversial in the literature,15,20 with conflicting reports of CSU remission after treatment with levothyroxine in some patients yet no such improvement in others.15,19,21 Several studies have reported that euthyroid patients with antithyroid antibodies can evolve to hypothyroidism during follow-up.16,21,22

In the present study, one of the patients presenting elevated ESR at baseline with no other symptoms, had arthralgia in interphalangeal joints of the hands after five years of follow-up and a final diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. The patient diagnosed with antiphospholipid antibody syndrome only reported episodes of thromboembolism during follow-up. Studies report that many individuals with autoimmune diseases, such as systemic erythematous lupus, dermatomyositis, polymyositis, Sjögren's syndrome, insulin-dependent diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis and Still's disease, can present CSU as the first presentation of the disease,19,20,22 and that urticaria can precede the symptoms of these diseases by several years,12,15,20 as occurred in the present study. Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies have been found to be significantly more prevalent in CSU patients than in the general population, even in patients without clinical symptoms of autoimmune diseases.15 The low number of autoimmune diseases observed in the present study may be because these diseases are treated in other sectors or due to the fact that only individuals with CSU, and no other clinical symptoms, were selected for inclusion.

Patients with primary immunodeficiencies predominantly of antibodies initially did not report any recurrent infections. After a number of visits, patients began to report episodes of recurrent otitis and tonsillitis, whose onset preceded that of urticaria. There was a similar occurrence involving the patient diagnosed with antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, underscoring the importance of the doctor-patient relationship during follow-up of CSU. No human immunoglobulin replacement was given for: IgA deficiency (not indicated) or IgG subclass deficiency (without pneumonias). Although urticaria persisted, the diagnosis was important to orient patients in the event of presenting with pneumonia. There are reports in the literature of CSU as the first clinical presentation of primary immunodeficiencies, predominantly of antibodies, with improvement in urticaria after human immunoglobulin replacement.23,24

Diagnosis of chronic myeloid leukaemia was reached based on pancytopenia observed during the initial investigation of the patient with urticaria referred as a CSU case. Cases of leukaemia, lymphomas, myelomas, genital-urinary and pulmonary tumours have been described, with remission of skin lesions in some cases after treatment.2,25,26 Diagnosing chronic myeloid leukaemia was important, as this may have influenced patient survival.

In the present study, urticaria in patients with positive skin tests for aeroallergens, correlated with allergic rhinitis symptoms, did not resolve after withdrawal of the allergen and treatment of the rhinitis. The literature shows that IgE reactions mediated by aeroallergens, medications and foods, rarely result in CSU, corroborated in the present investigation.1,2,4,27

The 45 patients with no new clinical symptoms during the ten-year follow-up were considered cases of CSU of unknown cause. Previous studies following patients for between 2 and 4 years28–30 reported that a diagnosis of CSU with unknown cause remains in around 50–70% of cases.5,7 Between 29% and 75% of children with CSU have normal complementary exams.31,32 Approximately 30–50% of individuals that have CSU of unknown cause exhibit IgG against the alpha subunit of the high affinity receptor of IgE in mastocytes while 5–10% produce IgG against IgE.7,21,33 Some reports suggest that these autoantibodies may have pathogenesis in urticaria, belong to IgG1 and igG3 subclasses, exhibit histamine-releasing activity and the ability to activate complement.7,18,33 The low number of SCU cases with unknown cause observed in the present study is likely due to the longer follow-up of the patients. All of the patients were followed throughout the ten-year study period and are still being monitored. After diagnosis of the diseases, the patients continued being followed at the Allergy Sector, and were also referred and followed within the specialised sectors for the different associated diseases. Patients with SCU of unknown cause required follow-up involving different specialties.

The present study benefited patients that had the initial diagnosis of CSU of unknown cause whose urticaria improved or disappeared after specific treatment of the associated diseases diagnosed during the long-term follow-up. We believe the present study reinforces the need for long-term follow-up in patients with CSU of unknown cause.

ConclusionWe conclude that this ten-year clinical-laboratory follow-up of 100 individuals initially diagnosed with CSU of unknown cause allowed the diagnosis of different associated diseases in over half of the cases: 29 infectious diseases (syphilis, parasitosis, H. pylori, urinary infection, tuberculosis, hepatitis B and C); 21 autoimmune diseases (thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome); four primary immunodeficiencies predominantly of antibodies (IgA and IgG2 subclass deficiencies); and one chronic myeloid leukaemia. The treatment of urinary infection, toxocariasis, giardiasis, hepatitis C, some cases of infection by H. pylori and of chronic myeloid leukaemia led to the disappearance of urticaria, more directly suggesting an association between the associated diseases and CSU.

In summary, we conclude that individuals initially diagnosed with CSU of unknown cause should be followed over the long-term, thereby allowing the diagnosis and treatment of different associated diseases that subsequently develop.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.