Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is a test used to evaluate the systemic inflammation. There is little knowledge about the neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio in asthmatics. In our study, we aimed to evaluate NLR and to assess its relationship with clinical parameters in children with asthma.

MethodsFour hundred and sixty-nine children diagnosed with asthma and followed in our hospital were included in the study. The control group included 170 children with no evidence of allergic disease (i.e. asthma, allergic rhinitis, eczema) or infection. Skin prick tests were performed using the same antigens for all patients. The immunoglobulin E levels and complete blood count were measured.

ResultsThere was no difference between the groups with regard to gender and age. Mean NLR was 2.07±1.41 in the study group and 1.77±1.71 in the control group. The difference was statistically significant (p=0.043). There was no statistically significant difference between NLR and gender, familial atopy, exposure to smoke, sensitivity to allergens (p>0.05). While mean NLR was weakly positively correlated with number of hospitalisations (r: 0.216; p: 0.012), the percentage of eosinophils was weakly negatively correlated with NLR (r: −0.195; p: 0.001).

ConclusionMean NLR is higher in asthmatic children compared to control group. We think that NLR could be used for the evaluation of systemic inflammation in asthmatic patients. However, further studies are needed to assess airway and systemic inflammation as well as NLR in patients with asthma.

Asthma is a chronic respiratory disease which affects 1–18% of the population in different countries. It is defined as a chronic inflammation of airways characterised by increased responsiveness of bronchials to a variety of stimuli. It is characterised by recurrent attacks of cough, wheezing, dyspnoea and by variable expiratory airflow limitation.1 In addition to airway inflammation, there is a systemic inflammation in asthma. The increased circulating proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-6 and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) play a role in this inflammation. These proinflammatory cytokines in asthmatic patients increase in immune cells, such as neutrophils and natural killer cells, and stimulate hepatic production of acute-phase proteins, such as C-reactive protein (CRP). C-reactive protein is known to be a sensitive marker of low-grade systemic inflammation.2,3 C-reactive protein is the most commonly used marker to evaluate the systemic inflammation in patients with asthma.3–9 Results with CRP levels in patients with asthma are inconsistent. Although some studies showed no difference in comparison with the control group,3,4 there are also some studies that observe CRP levels as higher in asthmatics than the control group.5–9 In addition to CRP, other acute phase reactants such as serum amyloid A and fibrinogen were evaluated in assessing the systemic inflammation in patients with asthma.5

Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR) could be an important measure of systemic inflammation as it is readily available, cost effective and could be calculated easily. NLR may reflect ethnicity, neurohumoral activation, renal dysfunction, thyroid disease, hepatic dysfunction, nutritional deficiencies, bone marrow dysfunction, inflammatory diseases, chronic or acute systemic inflammation.10 NLR has been associated with some conditions such as chronic inflammation in cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, malignancies, FMF, hepatic cirrhosis, and Behcet Disease, and it has been suggested that NLR has a prognostic importance.11–16 There is also a chronic inflammation in asthma. Cytokines in the pathogenesis of asthma cause an increase in neutrophils, as noted above.3 Based on this information, we think that the neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio is increased in asthmatics. However, our knowledge about NLR in asthmatic patients is less.11,17 While one of these studies performed in adults, showed no relationship between asthma and NLR,11 NLR was found to be associated with neutrophilic asthma in the other study.17

In our study, we aimed to evaluate NLR and to assess its relationship with clinical parameters in children with asthma.

MethodsFour hundred and sixty-nine children with asthma, followed in the Paediatric Allergy and Immunology Department of a public hospital of Obstetrics and Paediatrics, were included in the study. Patients were evaluated retrospectively between September 2012 and November 2014. The control group included 170 children with no evidence of allergic disease (i.e. asthma, allergic rhinitis, eczema) or infection.

Patients who have had an exacerbation of asthma, receiving systemic steroids within the last month, acute/chronic infection, and patients with any other systemic disease such as hepatic, renal, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, cancer and systemic inflammatory disorders were excluded. In addition, patients with anaemia/polycythemia, leukopenia/leukocytosis, and thrombocytopenia/thrombocytosis in complete blood count analysis were excluded from the study. Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio may be changed by medications such as Nebivolol.18 Therefore, patients receiving Nebivolol were excluded. A detailed allergic history, including the age, a familial atopy history, and exposure to cigarette smoke were recorded. Familial atopy was accepted as positive when having allergic disease in first degree relatives (parents and siblings). The diagnosis of asthma was evaluated according to the GINA guidelines.1 The immunoglobulin (Ig) E levels and complete blood count were measured. The study was approved by the Zeynep Kamil Woman's and Children's Diseases Training and Research Hospital Ethics committee and an oral consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their parents.

Skin prick testsSkin prick tests were performed using the same antigens for all patients. Patients were considered eligible for the skin test if they have not received antihistamines for at least one week. Skin prick tests were applied on the anterior forearm. Histamine (10mg/ml) and physiological saline were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Skin reactions were evaluated at the 15th minute of the application, and indurations ≥3mm were considered as a positive reaction. Skin prick tests for common aeroallergens (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Dermatophagoides farinea, grass mix, cereal mix, tree mix, weed mix, Alternaria alternaria, cockroaches, cat dander and dog dander (Stallergenes SA, 92160 Antony, France) were performed by using stallerpoint (Stallergenes SA, 92160 Antony, France).

Laboratory analysisHaemoglobin, platelet, leucocyte, neutrophil, and lymphocyte count measurements were performed within approximately 60min after blood sampling with Coulter LH 780 Analyzer and Coulter Hmx Haematology Analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Inc., CA, USA) with original method and reagents. Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio was calculated by dividing the percentage of neutrophils and lymphocytes in complete blood count analysis.

Statistical analysesStatistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS for Windows 15.0, Chicago, USA) programme was used to analyse the data. Results were given as either mean±standard deviation (SD) or as mean±standard deviation (median) according to the distribution. Student's t test was used for the comparison of normally distributed variables. Chi-square and Mann–Whitney U tests were used for non-normally distributed variables. Pearson's correlation test was used for the correlation analyses of continuous variables. p<0.05 was considered as significant.

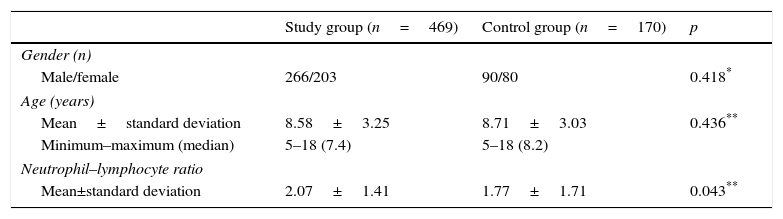

ResultsThe demographic and NLR of the study population are shown in Table 1. There was no difference between the groups with regard to gender and age. Mean NLR was 2.07±1.41 in the study group and 1.77±1.71 in the control group. The difference was statistically significant (p=0.043) (Table 1).

Comparison of socio-demographic and neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio between patients and control groups.

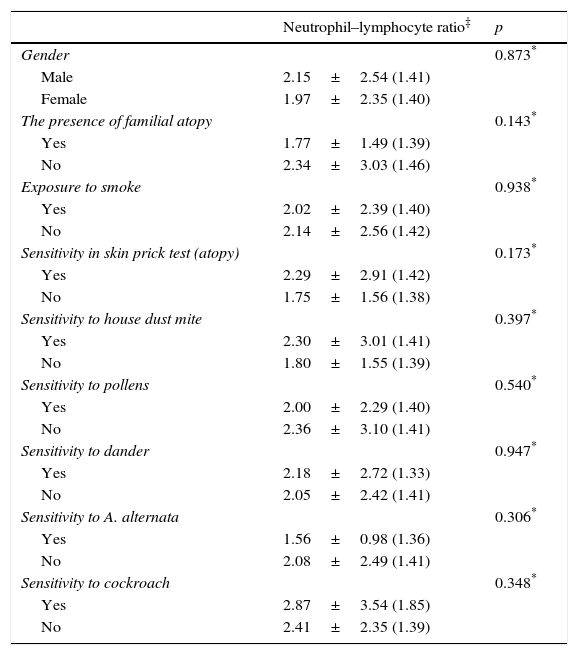

There was no statistically significant difference between NLR and gender, familial atopy, exposure to smoke, sensitivity to allergens (p>0.05) (Table 2).

Comparison of socio-demographic features, clinical and laboratory findings of the patient groups.

| Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio‡ | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.873* | |

| Male | 2.15±2.54 (1.41) | |

| Female | 1.97±2.35 (1.40) | |

| The presence of familial atopy | 0.143* | |

| Yes | 1.77±1.49 (1.39) | |

| No | 2.34±3.03 (1.46) | |

| Exposure to smoke | 0.938* | |

| Yes | 2.02±2.39 (1.40) | |

| No | 2.14±2.56 (1.42) | |

| Sensitivity in skin prick test (atopy) | 0.173* | |

| Yes | 2.29±2.91 (1.42) | |

| No | 1.75±1.56 (1.38) | |

| Sensitivity to house dust mite | 0.397* | |

| Yes | 2.30±3.01 (1.41) | |

| No | 1.80±1.55 (1.39) | |

| Sensitivity to pollens | 0.540* | |

| Yes | 2.00±2.29 (1.40) | |

| No | 2.36±3.10 (1.41) | |

| Sensitivity to dander | 0.947* | |

| Yes | 2.18±2.72 (1.33) | |

| No | 2.05±2.42 (1.41) | |

| Sensitivity to A. alternata | 0.306* | |

| Yes | 1.56±0.98 (1.36) | |

| No | 2.08±2.49 (1.41) | |

| Sensitivity to cockroach | 0.348* | |

| Yes | 2.87±3.54 (1.85) | |

| No | 2.41±2.35 (1.39) |

While mean NLR was weak positively correlated with number of hospitalisation (r: 0.216; p: 0.012), the percentage of eosinophil was weakly negatively correlated with NLR (r: −0.195; p: 0.001).

DiscussionThis study demonstrates for the first time that mean NLR in children with asthma is higher than healthy controls. The data about NLR in asthmatic patients is inadequate.11,17 In one of these studies, Imtiaz et al.11 investigated the relationship between the NLR and chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, asthma and arthritis in adults. They did not find a relationship between NLR and asthma. However, the diagnosis of asthma was ascertained by self-reporting in this study and NLR was not compared with control group. Therefore, their results may be in contradiction with our results. In the other study, Zhang et al.17 evaluated eosinophil and neutrophil percentages in sputum cytology and blood count of 164 patients with uncontrolled asthma. In this study, they determined that NLR increased in neutrophilic asthma. They concluded that neutrophilic asthma could also be detected by blood neutrophil percentages and NLR, but with less accuracy. Blood counts may be a useful aid in the monitoring of uncontrolled asthma.17 We could not evaluate the sputum cytology of asthmatic patients in our study. As mentioned in the introduction, we hypothesised that the neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio of asthmatic is high. In accordance with our hypothesis, we found that NLR in asthmatic children was higher compared to control.

Another important result of our study is that mean NLR was weakly positively correlated with number of hospitalisations. The relationship between NLR and the number of hospitalisations has not been evaluated before in the literature. But Schleich et al.19 reported a statistically significant correlation between sputum and percentage blood neutrophils. Zhang et al.17 similarly demonstrated that NLR (so neutrophils) was high in patients with neutrophilic asthma. Although we did not assess sputum cytology; taking into consideration the above results, we can predict that neutrophils in the sputum of patients with increased NLR is high. Furukawa et al.20 observed that enterance of asthmatic children with increased sputum neutrophils to emergency was higher. Consistent with this study, we found that mean NLR was weak positively correlated with number of hospitalisation. Additionally, systemic inflammation is more frequent in patients with neutrophilic asthma.7,8 In the study of Fu et al.21 they evaluated systemic inflammation in 50 asthmatic adults. They found that the number of neutrophils in sputum was more in the asthmatics with systemic inflammation (increased CRP and IL-6). In addition to this study, Gunay et al.22 investigated the NLR of 269 patients with COPD and showed that there was a positive correlation between CRP and NLR. Due to the reasons that neutrophils in the blood and NLR have a relation with the number of neutrophils in sputum, the systemic inflammation in neutrophilic asthmatics is high and there is a positive correlation between the NLR and CRP; we think that NLR may be used in the evaluation of systemic inflammation in asthma as well because it is easy, cost effective and could be calculated easily.

There are several potential limitations to this study. Firstly, other inflammatory parameters such as CRP in evaluating the systemic inflammation could not be evaluated in our patients. Secondly, we could not assess airway inflammation and sputum cytology in our patients. These investigations could not be done because our study was done retrospectively. Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, it is the first study which assesses the relationship between NLR and asthma in such a large population in childhood.

In conclusion, mean NLR is higher in asthmatic children compared to the control group. We think that NLR could be used for the evaluation of systemic inflammation in asthmatic patients. But further studies are needed to assess airway and systemic inflammation as well as NLR in patients with asthma.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human subjects and animals in researchProtection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Patients’ data protectionConfidentiality of data. The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestNone declared.