Drug hypersensitivity reactions (DHR) are common in the paediatric population, representing a public health problem. Recent studies have confirmed that the frequency of drug allergy is overestimated by both parents and physicians. The aim of this study is to determine the prevalence and risk factors of actual drug allergies in children admitted to a tertiary referral allergy centre.

MethodsMedical records covering the period of 2005–2010 of children with a history of DHR were reviewed. Demographic features of the patients and results of skin and drug provocation tests were noted. The European Network for Drug Allergy (ENDA) questionnaire was filled by using medical records and making phone calls with parents.

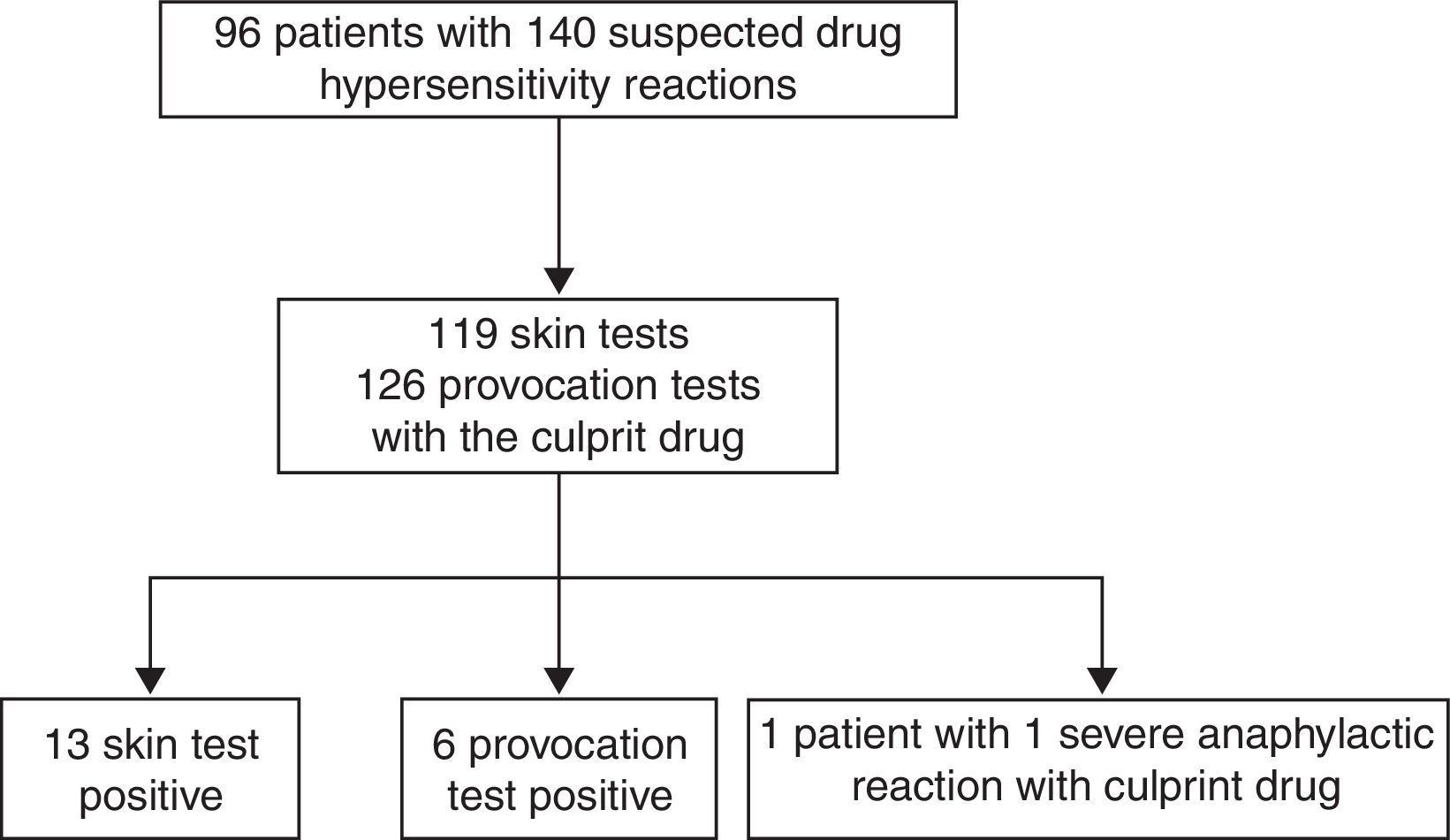

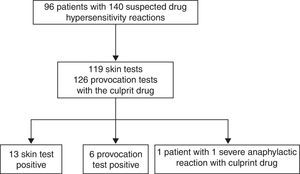

ResultsNinety-six patients with 140 DHRs were evaluated. Seventeen children had confirmed drug allergy by positive skin tests (n=11) and drug provocation tests (n=5). One patient underwent severe anaphylaxis and subsequent cardiac arrest during infusion of the drug, and therefore diagnostic tests were not performed. Actual drug allergy was more frequent in children with chronic diseases (58.8% vs. 26.5%, p=0.018) and histories of anaphylaxis during DHR (58.8% vs. 24%, p=0.001). The patients’ history of anaphylaxis [OR: 5.789, 95%CI: 1.880–17.554, p=0.002], sweating [OR: 7.8, 95%CI: 1.041–58.443, p=0.046] and dyspnoea [OR: 5.230, 95%CI: 1.836–14.894, p=0.002] during suspicious DHRs increased the risk for actual drug allergy.

ConclusionActual drug allergy was determined in 17.7% of the patients with a suspicious DHR. Having a history of anaphylaxis during suspected drug reactions as well as symptoms of sweating and dyspnoea increased the risk for actual drug allergy.

Drug hypersensitivity reactions (DHR) account for one third of all adverse drug reactions, and occur with a prevalence of 7% in the general population.1 It is difficult to confirm DHRs without diagnostic tests because symptoms may appear hours or days after the culprit drug intake and some patients may have other chronic diseases that disguise a DHR. Macular exanthemas often seen during childhood viral infections are the most common symptom of DHRs, thus requiring a diagnostic workup.2,3 Diagnosing a suspicious DHR results in use of more expensive and toxic drugs as alternatives, which create a major health problem.1,4–6 Therefore, patients consulted for a suspicious DHR must be carefully evaluated by a detailed history and validated skin tests when available, and drug provocation tests (DPT) if there is no contraindication.

This retrospective study aims to analyse the actual prevalence of drug allergies in patients who were referred to the paediatric allergy department of a tertiary health care centre over a five-year period due to a suspicious history of DHR and assessed using skin tests and DPTs. Additionally, the risk factors for actual drug allergy were investigated.

MethodsPatientsThe study was performed in the Paediatric Allergy Department of Hacettepe University İhsan Dogramaci Children's’ Hospital. The medical records of all patients who were referred due to a history of suspicious DHR from January 2005 to December 2010 were reviewed retrospectively. Demographic and clinical features of the patients were recorded and a European Network for Drug Allergy (ENDA) questionnaire was filled by using medical records and making phone calls with the parents of the patients.7 Demographic and clinical features included the patients’ personal and family histories of allergies and any other chronic diseases diagnosed by a physician. Results of skin tests and DPTs for suspected DHRs were recorded, as well as a skin prick test (SPT) for aeroallergens, if available. These aeroallergen tests [grass pollen mix (Phleum pratense, Poa pratensis, Dactylis glomerata, Lolium perenne, Festuca pratensis, Avena sativa, Cynodon dactylon), weed pollen mix (Parietaria judaica, Artemisia vulgaris, Plantago, Chenopodium, Salsola kali), tree pollen mix (Salix caprea, Ulmus campestris, Quercus robur, Corylus avellana, Betula alba, Populus alba, Platanus vulgaris, Olea europaea), house dust mites (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Dermatophagoides farinae), animal dander (cat and dog), moulds (Alternaria alternata, Cladosporium herbarum) and cockroach (Blattella germanica)] had been applied only to those patients with a history of respiratory allergy. Immediate and non-immediate reactions were defined as DHR occurrence within one hour and later than one hour after the culprit drug intake, respectively.8 Detailed information was recorded regarding suspected DHR concerning any administered medications, admission to the emergency department, and hospitalisation for DHR treatment. Drug-related anaphylaxis was classified as mild, moderate or severe, in accordance with European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology guidelines.9 Valid protocols were used for SPTs, intradermal tests (IDT)s, and DPTs in accordance with ENDA recommendations.10,11 Tests were performed in the patients who had not taken antihistamines or any other drugs incompatible with diagnostic tests in the previous week. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hacettepe University School of Medicine.

Skin testsExperienced nurses in our department performed SPTs with the culprit drug, histamine (10mg/ml of histamine phosphate) as positive and 0.9% sterile saline as negative controls. First, SPT with the culprit drug was applied (1/10th concentration and full strength). Negative SPTs were followed by the intradermal administration of the culprit drug starting with more diluted concentrations at the minimum non-irritating concentration (1/100th for anaphylactic DHRs, then 1/10th, and full strength). If a negative result was obtained with the most diluted concentration after 20min, the IDT continued until the concentration of the culprit drug reached the minimum allowable strength, or a positive result was obtained. SPT or IDT with the culprit drug was defined as positive if there appeared a wheal of at least 3mm greater in diameter than that of saline, accompanied by erythema. Skin tests for beta-lactam allergy were carried out according to ENDA recommendations.12

Drug provocation testsAn experienced physician performed DPTs with full resuscitation back-up under strict hospital surveillance on patients with negative skin tests or if the skin test with culprit drug was invalid. DPT began by administering 1/10th to 1/100th of the required therapeutic dose of the culprit drug. Doses increased every 30min until a positive reaction was obtained or until reaching the total therapeutic dose, which was calculated according to the patient's body weight.11 The test was stopped if any skin-related (urticaria, angio-oedema, maculopapular rash, etc.), respiratory (cough, wheezing, dyspnoea, etc.), cardiovascular (hypotension, tachycardia, etc.), neurological (confusion, syncope, etc.) and gastrointestinal (abdominal pain, vomiting, etc.) symptoms occurred. DPT was declared positive if any of these objective symptoms appeared which are associated with a history for suspicious DHR. Patients with positive DPTs were treated accordingly and monitored until the symptoms disappeared.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed by SPSS 15.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) software. Statistical comparison among disease groups was performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test for non-normally distributed variables, and the One-Way ANOVA for normally distributed variables. Pearson's chi-square test compared categorical variables. Two different data sets were developed: one for demographic and clinical features of the patients and the other for features of the suspicious DHRs. Additionally, univariate and multivariate analyses were performed and odds ratios (ORs) with relevant 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to assess the potential relationship between various predictors and actual drug allergies in both of the data sets. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

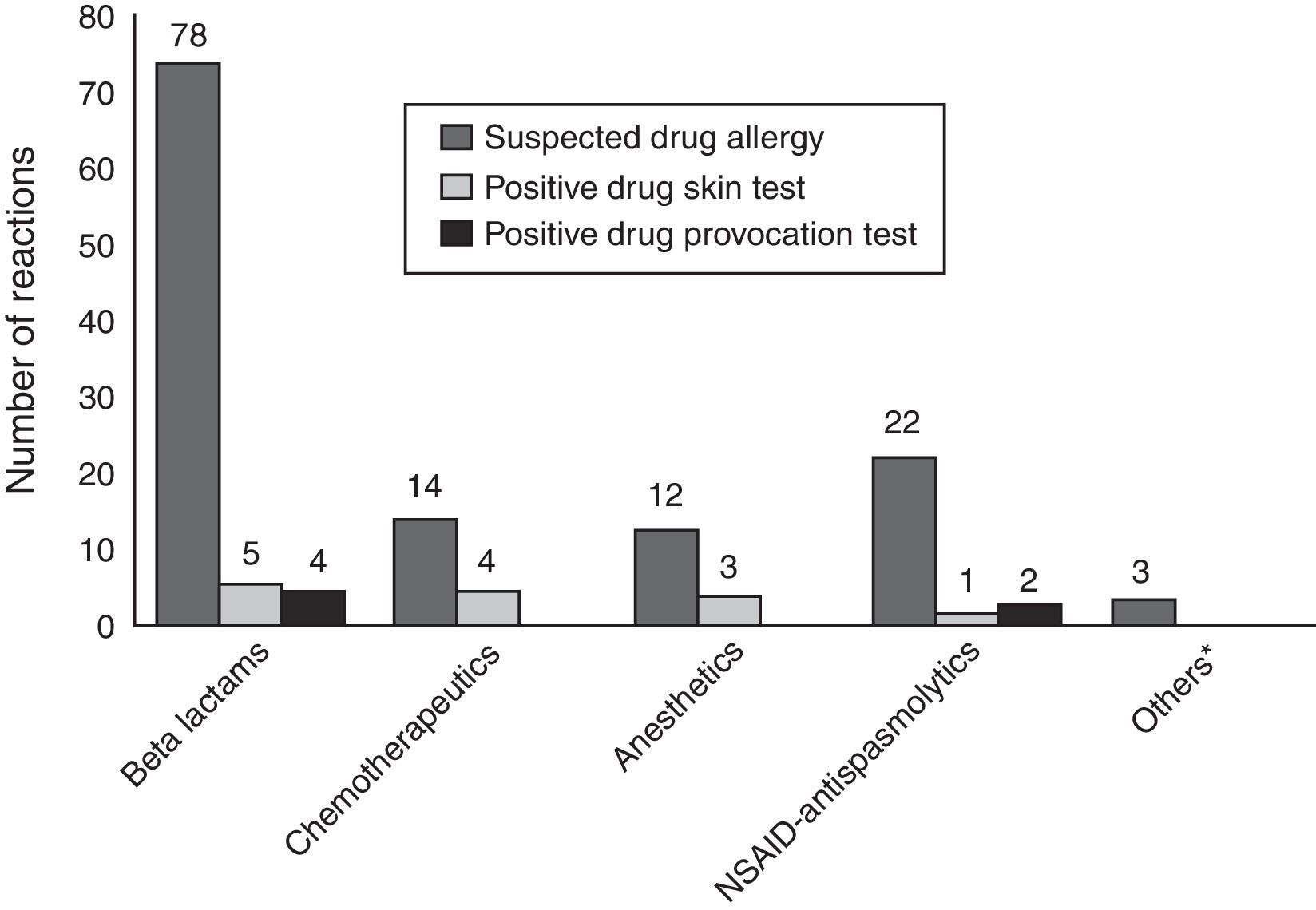

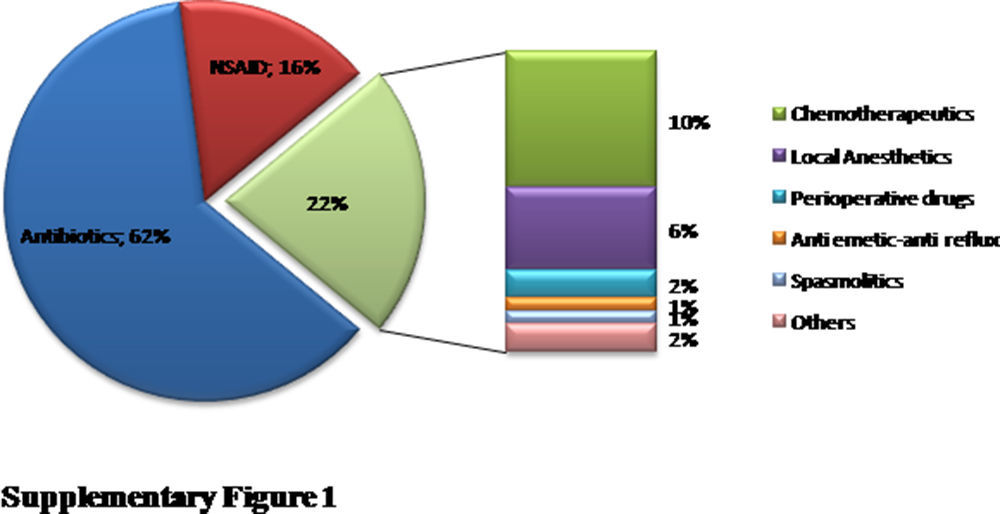

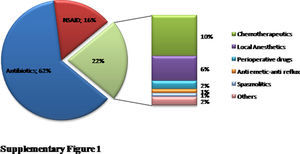

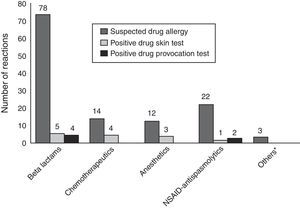

ResultsA total of 96 patients [7.5 (5.31–11) years, median (interquartile range), 51% male] with 140 DHRs were assessed over a five-year period (Fig. 1). A history of anaphylaxis was present in 42 (31.3%) of all DHRs, 9 (21.4%) of them being severe. During DHRs, the most common symptoms were cutaneous manifestations (90%) the majority of which occurred as urticaria (79.3%) and angio-oedema (45%). Respiratory symptoms were found in 27.1% of the reactions, mostly dyspnoea (24.2%) and wheezing (10%). During drug allergy work-up, the most frequent differential diagnosis was viral infections (32.5%, n=14) followed by recurrent urticaria and/or angio-oedema (n=12), vasovagal syncope (n=9), local reaction at the injection site (n=7), panic-attack (n=4), and acute gastroenteritis (n=3). The culprit drugs used during these DHRs were antibiotics (n=87, 62%), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (n=22, 16%), chemotherapeutics (l-asparaginase, n=14, 10%), local anaesthetics [in total n=9, (6%), articaine (n=6), prilocaine (n=1), procaine (n=1), lidocaine (n=1)], perioperative drugs (muscle relaxants and general anaesthetics) (n=3, 2%) and the others (antiemetics and spasmolytics, n=5, 4%) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Beta-lactams [(amoxicillin-clavulanate (41%, n=36), penicillin (25%, n=22), cephalosporins (16%, n=14), and ampicillin (7%, n=6)] were the most frequently suspected antibiotic group. Clarithromycin (8%, n=7) was the most common culprit drug among non-beta-lactam antibiotics. Paracetamol, ibuprofen, and metamizole were used equally as culprit NSAIDs during suspicious DHRs.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aller.2015.01.005.

The indications for drug use were infections in majority of the DHRs (75%), with acute tonsillitis (40%) being the most frequent. Malignancy was the second most common disease group with a frequency of 10.7%. Suspicious DHRs mainly occurred after the first dose of the drug (57%). Adrenaline was required in 24 reactions (17.1%) and patients were hospitalised in 18 reactions (12.8%) due to anaphylaxis.

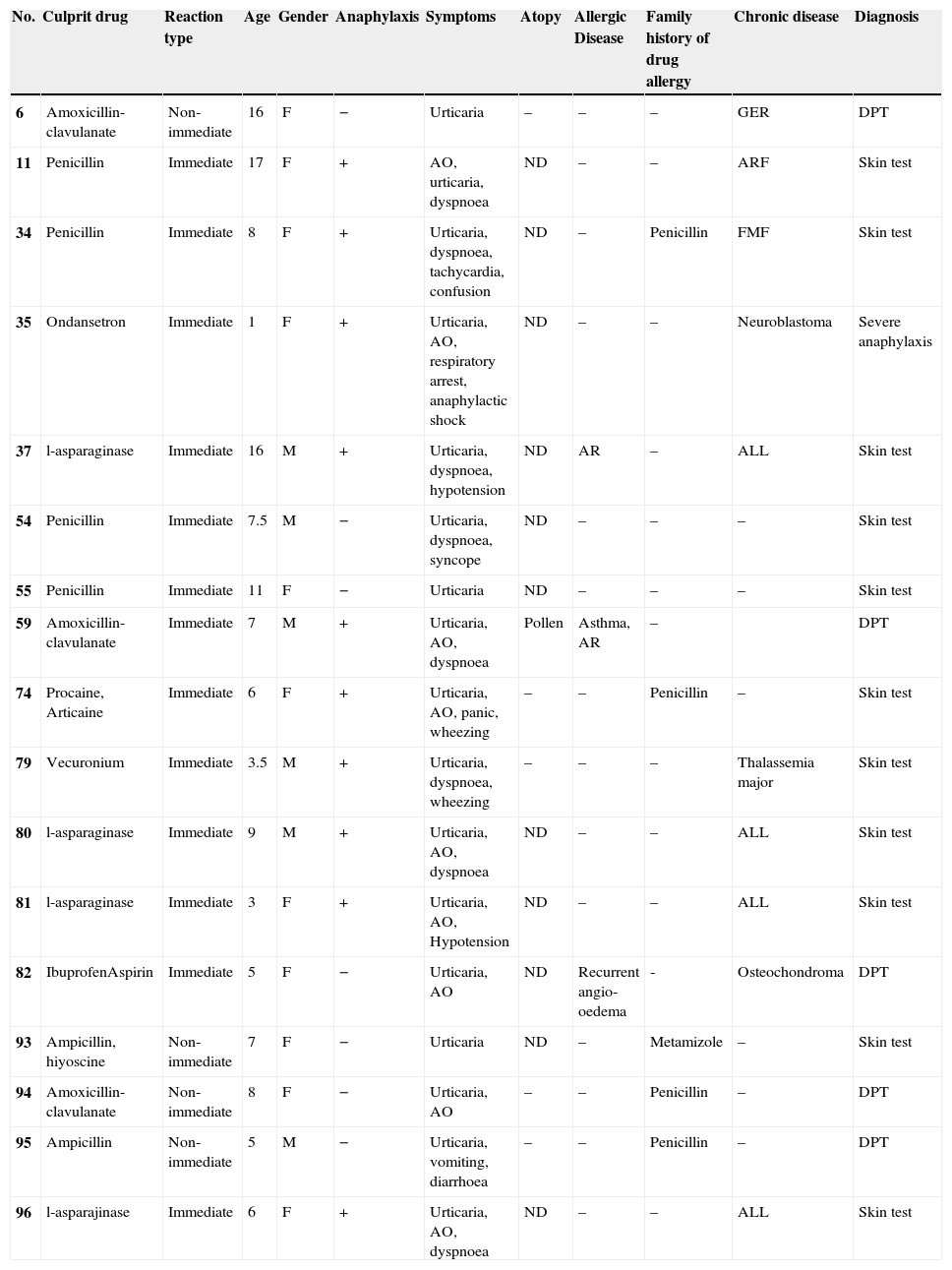

Regarding all diagnostic tests, 13 skin tests were positive in 11 patients out of 119 culprit drugs (Table 1; Fig. 1). A DPT was done for 126 of 140 suspicious reactions (90%), six of which were positive in five patients (Table 1; Fig. 1). Patient 96 developed an immediate reaction during drug provocation even though the DHR history was non-immediate type. Patient 35 underwent severe anaphylaxis due to ondansetron, so a diagnostic test was not performed with ondansetron. The patient had been diagnosed with neuroblastoma and she experienced severe cyanosis, apnoea which developed in seconds while she was on intravenous ondansetron infusion and was hospitalised at the oncology service in our institution. Granisetron was chosen as a safe alternative for this patient, and skin and provocation tests were negative.13 The diagnosis of actual drug allergy was made in 17 patients for 20 suspicious DHRs. SPTs diagnosed 13 reactions in 11 patients, DPTs diagnosed six reactions in five patients and one patient was diagnosed through experiencing severe anaphylaxis during intravenous administration of the culprit drug under physician supervision in our hospital (Fig. 2).

Characteristic features of the patients and the reactions with actual drug allergy.

| No. | Culprit drug | Reaction type | Age | Gender | Anaphylaxis | Symptoms | Atopy | Allergic Disease | Family history of drug allergy | Chronic disease | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Amoxicillin-clavulanate | Non-immediate | 16 | F | − | Urticaria | – | – | – | GER | DPT |

| 11 | Penicillin | Immediate | 17 | F | + | AO, urticaria, dyspnoea | ND | – | – | ARF | Skin test |

| 34 | Penicillin | Immediate | 8 | F | + | Urticaria, dyspnoea, tachycardia, confusion | ND | – | Penicillin | FMF | Skin test |

| 35 | Ondansetron | Immediate | 1 | F | + | Urticaria, AO, respiratory arrest, anaphylactic shock | ND | – | – | Neuroblastoma | Severe anaphylaxis |

| 37 | l-asparaginase | Immediate | 16 | M | + | Urticaria, dyspnoea, hypotension | ND | AR | – | ALL | Skin test |

| 54 | Penicillin | Immediate | 7.5 | M | − | Urticaria, dyspnoea, syncope | ND | – | – | – | Skin test |

| 55 | Penicillin | Immediate | 11 | F | − | Urticaria | ND | – | – | – | Skin test |

| 59 | Amoxicillin-clavulanate | Immediate | 7 | M | + | Urticaria, AO, dyspnoea | Pollen | Asthma, AR | – | DPT | |

| 74 | Procaine, Articaine | Immediate | 6 | F | + | Urticaria, AO, panic, wheezing | – | – | Penicillin | – | Skin test |

| 79 | Vecuronium | Immediate | 3.5 | M | + | Urticaria, dyspnoea, wheezing | – | – | – | Thalassemia major | Skin test |

| 80 | l-asparaginase | Immediate | 9 | M | + | Urticaria, AO, dyspnoea | ND | – | – | ALL | Skin test |

| 81 | l-asparaginase | Immediate | 3 | F | + | Urticaria, AO, Hypotension | ND | – | – | ALL | Skin test |

| 82 | IbuprofenAspirin | Immediate | 5 | F | − | Urticaria, AO | ND | Recurrent angio-oedema | - | Osteochondroma | DPT |

| 93 | Ampicillin, hiyoscine | Non-immediate | 7 | F | − | Urticaria | ND | – | Metamizole | – | Skin test |

| 94 | Amoxicillin-clavulanate | Non-immediate | 8 | F | − | Urticaria, AO | – | – | Penicillin | – | DPT |

| 95 | Ampicillin | Non-immediate | 5 | M | − | Urticaria, vomiting, diarrhoea | – | – | Penicillin | – | DPT |

| 96 | l-asparajinase | Immediate | 6 | F | + | Urticaria, AO, dyspnoea | ND | – | – | ALL | Skin test |

AO: angio-oedema, AR: allergic rhinitis, DPT: drug provocation test, GER: gastro-oesophageal reflux, ARF: acute rheumatic fever, FMF: familial mediterranean fever, ALL: acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.

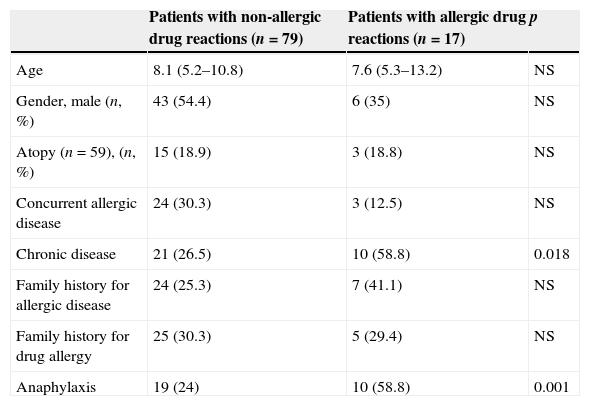

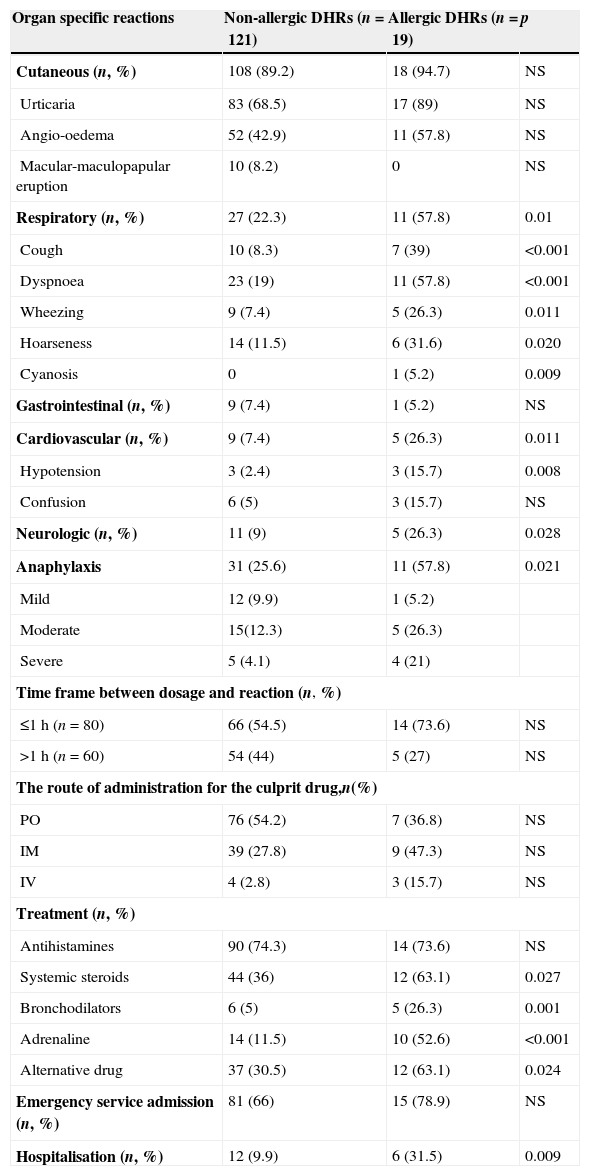

Actual drug allergy was more frequent in children with chronic diseases (58.8% vs. 26.5%, p=0.018) and a history of anaphylaxis during DHR (58.8% vs. 24%, p=0.001), compared to children without drug allergies (Table 2). Respiratory symptoms (cough, dyspnoea, hoarseness, cyanosis) and hypotension occurred more frequently in actually allergic drug reactions compared to non-allergic ones [(58.8% vs. 22.3%, p=0.001) and (15.7% vs. 2.4% p=0.008), respectively], (Table 3). Adrenaline, systemic steroid and bronchodilator use, and hospitalisation were more frequently required to treat allergic drug reactions compared to non-allergic ones, [(52.6% vs. 11.5%, p<0.001), (63.1% vs. 36%, p=0.027), (26.3% vs. 5%, p=0.001), (31.5% vs. 9.9%, p=0.009)], respectively (Table 3).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients according to diagnosis of actual drug allergy.

| Patients with non-allergic drug reactions (n=79) | Patients with allergic drug reactions (n=17) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 8.1 (5.2–10.8) | 7.6 (5.3–13.2) | NS |

| Gender, male (n, %) | 43 (54.4) | 6 (35) | NS |

| Atopy (n=59), (n, %) | 15 (18.9) | 3 (18.8) | NS |

| Concurrent allergic disease | 24 (30.3) | 3 (12.5) | NS |

| Chronic disease | 21 (26.5) | 10 (58.8) | 0.018 |

| Family history for allergic disease | 24 (25.3) | 7 (41.1) | NS |

| Family history for drug allergy | 25 (30.3) | 5 (29.4) | NS |

| Anaphylaxis | 19 (24) | 10 (58.8) | 0.001 |

NS: non-significant.

Clinical characteristics of suspicious DHRs according to diagnosis of actual drug allergy.

| Organ specific reactions | Non-allergic DHRs (n=121) | Allergic DHRs (n=19) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cutaneous (n, %) | 108 (89.2) | 18 (94.7) | NS |

| Urticaria | 83 (68.5) | 17 (89) | NS |

| Angio-oedema | 52 (42.9) | 11 (57.8) | NS |

| Macular-maculopapular eruption | 10 (8.2) | 0 | NS |

| Respiratory (n, %) | 27 (22.3) | 11 (57.8) | 0.01 |

| Cough | 10 (8.3) | 7 (39) | <0.001 |

| Dyspnoea | 23 (19) | 11 (57.8) | <0.001 |

| Wheezing | 9 (7.4) | 5 (26.3) | 0.011 |

| Hoarseness | 14 (11.5) | 6 (31.6) | 0.020 |

| Cyanosis | 0 | 1 (5.2) | 0.009 |

| Gastrointestinal (n, %) | 9 (7.4) | 1 (5.2) | NS |

| Cardiovascular (n, %) | 9 (7.4) | 5 (26.3) | 0.011 |

| Hypotension | 3 (2.4) | 3 (15.7) | 0.008 |

| Confusion | 6 (5) | 3 (15.7) | NS |

| Neurologic (n, %) | 11 (9) | 5 (26.3) | 0.028 |

| Anaphylaxis | 31 (25.6) | 11 (57.8) | 0.021 |

| Mild | 12 (9.9) | 1 (5.2) | |

| Moderate | 15(12.3) | 5 (26.3) | |

| Severe | 5 (4.1) | 4 (21) | |

| Time frame between dosage and reaction (n, %) | |||

| ≤1h (n=80) | 66 (54.5) | 14 (73.6) | NS |

| >1h (n=60) | 54 (44) | 5 (27) | NS |

| The route of administration for the culprit drug,n(%) | |||

| PO | 76 (54.2) | 7 (36.8) | NS |

| IM | 39 (27.8) | 9 (47.3) | NS |

| IV | 4 (2.8) | 3 (15.7) | NS |

| Treatment (n, %) | |||

| Antihistamines | 90 (74.3) | 14 (73.6) | NS |

| Systemic steroids | 44 (36) | 12 (63.1) | 0.027 |

| Bronchodilators | 6 (5) | 5 (26.3) | 0.001 |

| Adrenaline | 14 (11.5) | 10 (52.6) | <0.001 |

| Alternative drug | 37 (30.5) | 12 (63.1) | 0.024 |

| Emergency service admission (n, %) | 81 (66) | 15 (78.9) | NS |

| Hospitalisation (n, %) | 12 (9.9) | 6 (31.5) | 0.009 |

PO: peroral; IM: intramuscular; IV: intravenous; DHR: drug hypersensitivity reaction.

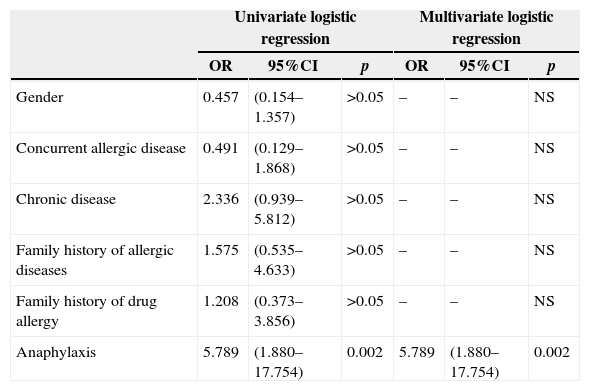

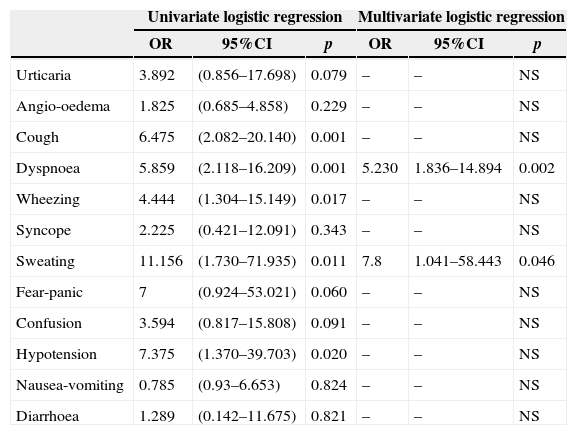

A history of anaphylaxis in the patient during suspicious DHR increased the risk of an actual drug allergy (OR: 5.789, 95%CI: 1.880–17.554, p=0.002), (Table 4a). Occurrence of dyspnoea (OR: 5.230, 95%CI: 1.836–14.894, p=0.002) and sweating (OR: 7.8, 95%CI: 1.041–58.443, p=0.046) during suspicious DHR also increased a patient's risk of actual drug allergy (Table 4b).

Logistic regression analysis for the patients for actual drug allergy.

| Univariate logistic regression | Multivariate logistic regression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | p | OR | 95%CI | p | |

| Gender | 0.457 | (0.154–1.357) | >0.05 | – | – | NS |

| Concurrent allergic disease | 0.491 | (0.129–1.868) | >0.05 | – | – | NS |

| Chronic disease | 2.336 | (0.939–5.812) | >0.05 | – | – | NS |

| Family history of allergic diseases | 1.575 | (0.535–4.633) | >0.05 | – | – | NS |

| Family history of drug allergy | 1.208 | (0.373–3.856) | >0.05 | – | – | NS |

| Anaphylaxis | 5.789 | (1.880–17.754) | 0.002 | 5.789 | (1.880–17.754) | 0.002 |

CI: confidence interval, OR: Odds ratio.

Logistic regression analysis for the reactions with actual drug allergy.

| Univariate logistic regression | Multivariate logistic regression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | p | OR | 95%CI | p | |

| Urticaria | 3.892 | (0.856–17.698) | 0.079 | – | – | NS |

| Angio-oedema | 1.825 | (0.685–4.858) | 0.229 | – | – | NS |

| Cough | 6.475 | (2.082–20.140) | 0.001 | – | – | NS |

| Dyspnoea | 5.859 | (2.118–16.209) | 0.001 | 5.230 | 1.836–14.894 | 0.002 |

| Wheezing | 4.444 | (1.304–15.149) | 0.017 | – | – | NS |

| Syncope | 2.225 | (0.421–12.091) | 0.343 | – | – | NS |

| Sweating | 11.156 | (1.730–71.935) | 0.011 | 7.8 | 1.041–58.443 | 0.046 |

| Fear-panic | 7 | (0.924–53.021) | 0.060 | – | – | NS |

| Confusion | 3.594 | (0.817–15.808) | 0.091 | – | – | NS |

| Hypotension | 7.375 | (1.370–39.703) | 0.020 | – | – | NS |

| Nausea-vomiting | 0.785 | (0.93–6.653) | 0.824 | – | – | NS |

| Diarrhoea | 1.289 | (0.142–11.675) | 0.821 | – | – | NS |

CI: confidence interval, OR: Odds ratio.

In this study, the ratio for actual drug allergy among suspicious DHRs was found to be 17.7% in a tertiary referral centre. This rate is rather higher than other surveys indicate. In a cross-sectional study of the Black Sea region of Turkey, the prevalence of parentally-reported drug allergy was found to be 2.8% among 2855 children aged from 6 to 9 years14. In France, parentally-reported drug allergy prevalence among 1426 children was 4.6% (n=67), however skin and provocation tests ultimately diagnosed only three of them (4.5%) as genuinely allergic to the culprit drug.15 The main reason for the high rate of drug allergy in our study might be due to our department being a tertiary allergy clinic that serves as a reference centre.

Another factor contributing to such a rate of actual drug allergy might be the high number of patients with chronic diseases among the study participants. Use of the culprit drug or any other cross-reactive drug in chronic or recurrent treatment schedules increases the risk for drug sensitivity. Acute allergic drug reactions to beta-lactam antibiotics are observed in cystic fibrosis patients three times more frequently than in the general population.16 In cases of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, 16.2% of patients were found to have a drug allergy for l-asparaginase.17 This study found that chronic diseases were significantly more frequent among drug-allergic patients than drug-tolerant ones. Our hospital also serves as a reference centre for children with chronic diseases.

DHR affects different systems in the body according to severity and aetiology. In a group of children with suspected adverse drug reactions, the most frequent symptoms were skin-related (62%) followed by gastrointestinal (26%) and respiratory systems (20%).15 According to parental reports, allergic drug reactions primarily affected skin (93.8%), followed by gastrointestinal (21%), and respiratory system (9.9%).14 In parallel with these findings, cutaneous symptoms were prominent in our study but respiratory and neurological symptoms were encountered more frequently than previously reported. Patients in our study with actual drug allergies exhibited more severe DHRs such as anaphylaxis.

The major cutaneous symptoms seen during DHRs are maculopapular rash, urticaria and angio-oedema.6,18,19 Angio-oedema/urticaria were seen in 70.4% of allergic reactions to beta-lactam antibiotics, followed by maculopapular rash (18.4%) in 1431 patients with immediate and non-immediate DHRs.20 In a prospective study of hospitalised patients in Mexico, the most frequent cutaneous symptoms during adverse drug reactions were morbilliform rash (51.2%) followed by urticaria (12.2%) and erythema multiforme (4.9%).21 However, macular or maculopapular eruptions appeared in 7.1% of all suspicious DHRs in our study, and none of these were actual allergic drug reactions. This low percentage of maculopapular eruptions in our study may be explained by low association of drug allergy as aetiology of mild maculopapular rashes by parents,2,22 and referral of patients with more severe reactions to a tertiary centre.

Drug intake is the second most common cause of acute anaphylaxis after insect bites in the USA23 and Britain,24 but it is the most common cause in Italy.25 Pumprey et al. reported an increased prevalence and hospitalisation rate due to anaphylaxis and showed that the most frequent cause of mortality due to anaphylaxis was drugs.26,27 A multicentre study in paediatric patients showed that acute anaphylaxis was caused primarily by food allergies (38.4%), followed by insect bites (37.5%) and drugs (21%).28 A history of anaphylaxis was found in 6.9% of suspicious beta-lactam-related hypersensitivity reactions in children, and a patient's history of anaphylaxis was a distinct sign of actual beta-lactam allergy (p<0.001).20 This study found a direct relationship of drug-related anaphylaxis and the resultant hospitalisation during suspicious DHRs with actual drug allergy. Additionally, logistic regression analysis showed that a patient's history of anaphylaxis with suspicious DHR increased the risk of actual drug allergy.

The attitude of the physician who initially deals with the patient with a suspected DHR is very important for both acute treatment of the patient and guiding him/her to an allergy specialist for further diagnostic testing, pertinent education and discussion of the prevention strategies for all kinds of DHRs. Drugs compose a significant portion of the aetiological factors for anaphylaxis29 and anaphylaxis-related fatalities, the rates of which have been increasing for the last decade.30 For acute treatment of drug-induced anaphylaxis, prompt injection of adrenaline is the first thing to do which is confirmed by evidence-based medicine.31 However it is important to note that not all physicians are aware of the exact necessity of adrenaline in cases of drug-induced anaphylactic reactions and additionally only a very low number of patients had referred to an allergy specialist.32

Drug allergy diagnosis is based on skin tests and DPTs. Demoly and Gomes showed that 19% of patients with cutaneous symptoms due to beta-lactams were diagnosed as allergic to penicillin via SPTs.6 Among patients whose skin tests were negative 8–17% were diagnosed as allergic to penicillin via DPTs.33,34 In this study, half of the patients with penicillin allergy were diagnosed via skin tests and the other half via DPTs. This result showed the importance of confirming the patient's actual drug allergy, not only with skin tests but also with DPTs, during diagnostic assessment of suspicious DHRs.

Parents or patients may not be able to discern all signs and symptoms of a suspicious DHR in detail when relating their medical history. Guidance from the ENDA questionnaire gives us the most accurate and objective data about DHRs. It may not be possible to use this questionnaire in emergency settings with a high number of patients where operative questions should be asked in a limited time period. In this study, the symptoms during the suspicious DHR were assessed in detail and a history of sweating and dyspnoea during the reaction were defined as risk factors for the diagnosis of a genuine drug allergy. Dyspnoea, an important symptom of anaphylaxis, was observed in 34% of patients with mild to moderate anaphylaxis and 55% of patients with severe anaphylaxis.35 Patients with atopic diseases like asthma have an increased sensitivity to cholinergic stimuli.36 An increased hypersensitivity to cholinergic stimuli and/or an increased activation of the cholinergic system, usually observed as an increase in sweating, may occur during anaphylactic reactions.37 During evaluation of drug allergy history, symptoms of dyspnoea and sweating during suspicious DHR might be a sign of an actual drug allergy, along with gastrointestinal and cardiovascular symptoms. Sweating as a symptom of actual drug allergy is a novel finding, and we expect that there should be further studies on the link between sweating and drug allergy.

Our study faced some limitations. The data related to suspicious DHRs were retrospective, retrieved from medical records and from the patients’ parents, and therefore inherently incomplete. Additionally, SPTs with aeroallergens were not applied to the entire study group, instead performed only on the patients who had a history of symptoms related to atopic disease.

In conclusion, we investigated the relation between symptoms and demographic features of child patients who had been diagnosed with a drug allergy, but found actual drug allergies in 17.7% of patients with suspicious DHRs. Additionally, it was shown that actual drug allergy was more frequent among patients with chronic diseases. The history of anaphylaxis during suspected drug reactions as well as symptoms of sweating and dyspnoea increase the risk of actual drug allergy. These findings may guide future studies on drug allergies in childhood.

Conflict of interestAll the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest regarding this article.

FundingNone.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThis study was designed as the retrospective review of patients evaluated for drug hypersensitivity and ethical approval was obtained from Ethics Committee of Hacettepe University Medical Faculty. Since this was a retrospective review according to rules of the Ethics committee which is in line with Declaration of Helsinki the written informed consent was not needed.