We present the case of a 65-year-old woman, who presented herself at the allergy outpatient clinic because on her last holiday trip to Malaysia she had developed acute angio-oedema of the eyes, dysphagia and dyspnoea ten minutes after the intake of a large breakfast, which consisted of scrambled eggs and roasted potatoes, which had been tolerated before and after, and – for the first time – meat loaf. The hotel's kitchen revealed the ingredients consisting in beef, potato flower, chicken stock and isolated soy protein-soya bean paste but no peanut. The meat loaf had been broiled but not cooked through. The patient reported no other allergies apart from intermittent, vernal rhinoconjunctivitis.

Skin prick tests were performed with commercial extracts (HAL, Cologne, Germany) of routine inhaled and nutritive allergens on the volar side of the forearm. Saline served as a negative, and histamine (10mg/ml, ALK- Abello, Linz, Austria) as a positive control. A wheal ≥3mm in diameter was considered as positive.

Total and specific IgE (sIgE) were determined with the ImmunoCAP system (Phadia AB, Uppsala, Sweden), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

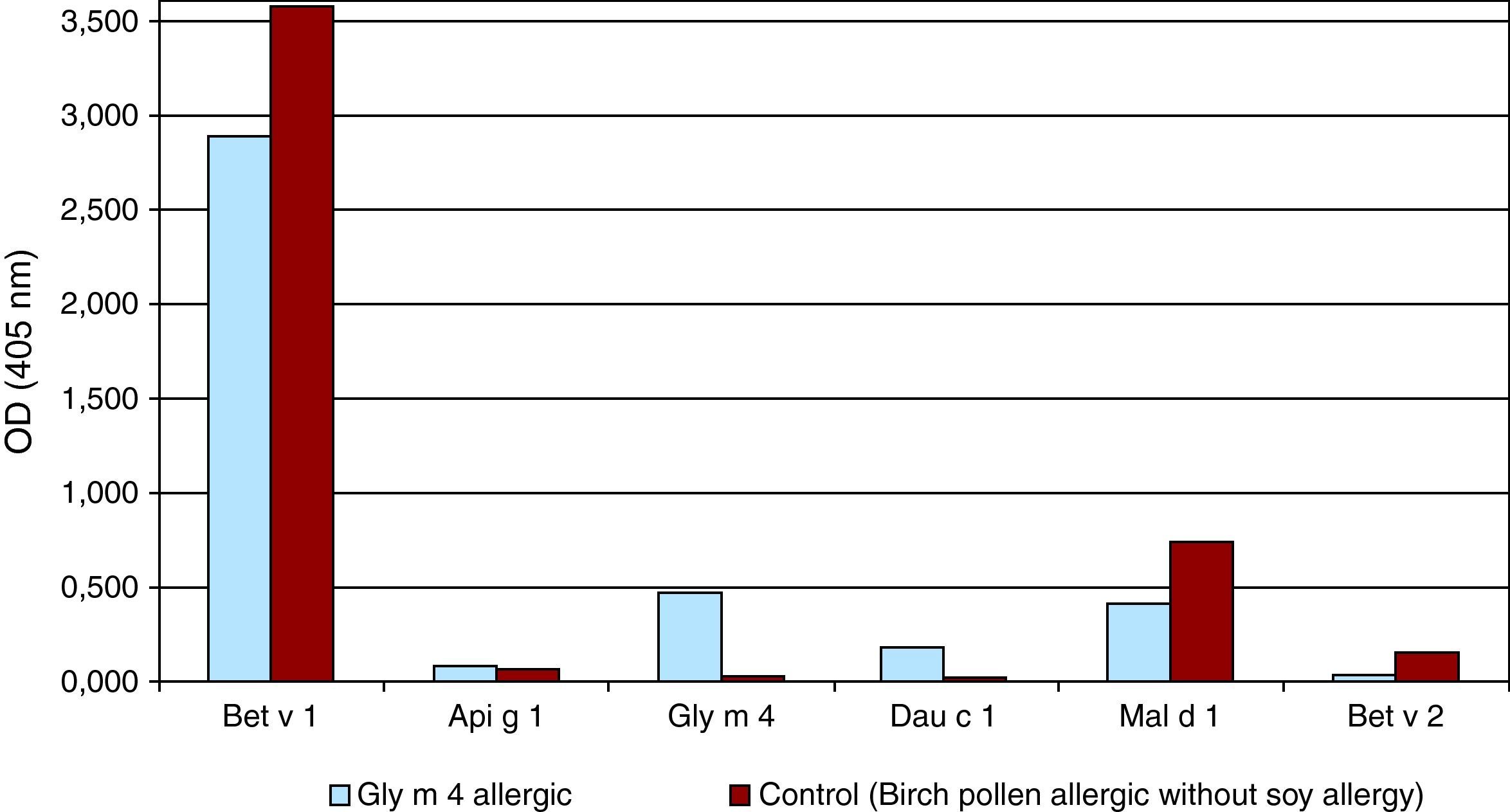

For IgE ELISAs Microtiter plates (MaxiSorp Immuno Plate, Nalge Nunc International, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with 0.5μg allergens (rBet v 1, rApi g 1, rGly m 4, rDau c 1, rMal d 1 and Bet v 1 as a negative control) per well overnight at 4°C. After blocking with Tris-buffered saline (TBS), 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20 and 1% (w/v) BSA, 1:4 diluted sera were applied onto the coated plates and incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing, the plates were incubated with a 1:1000 diluted alkaline phosphatase-conjugated mouse anti-human IgE antibody (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) for 2h at room temperature. Colour development was performed using 0.1% (w/v) disodium p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) and the optical density was measured at 405nm (550nm as reference wavelength) after 30minutes. Serum of a birch pollen-allergic patient without soy allergy and sera of three non-allergic subjects were used as negative controls. OD values were considered positive if they exceeded the mean OD of the negative controls by more than three standard deviations.

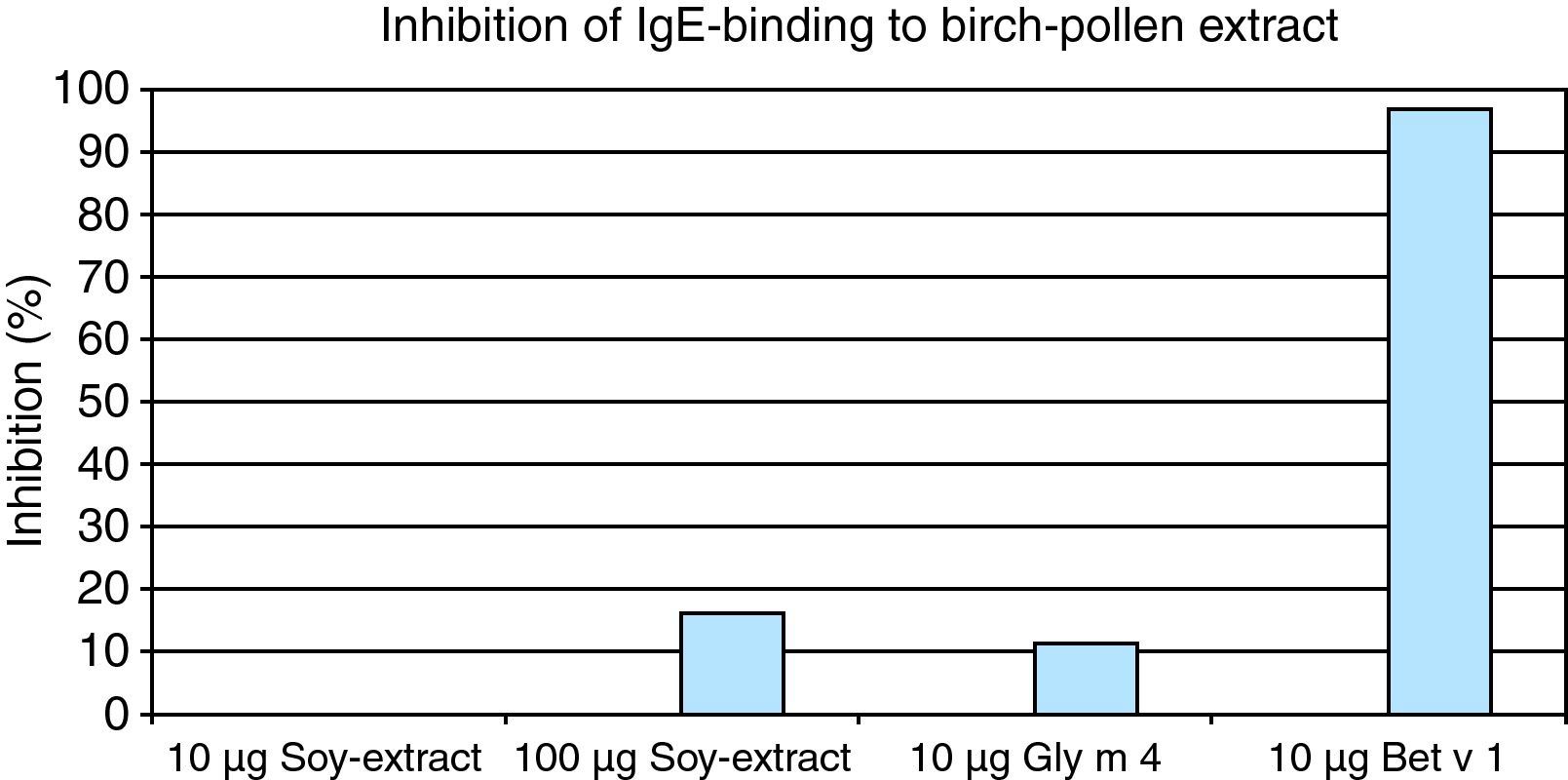

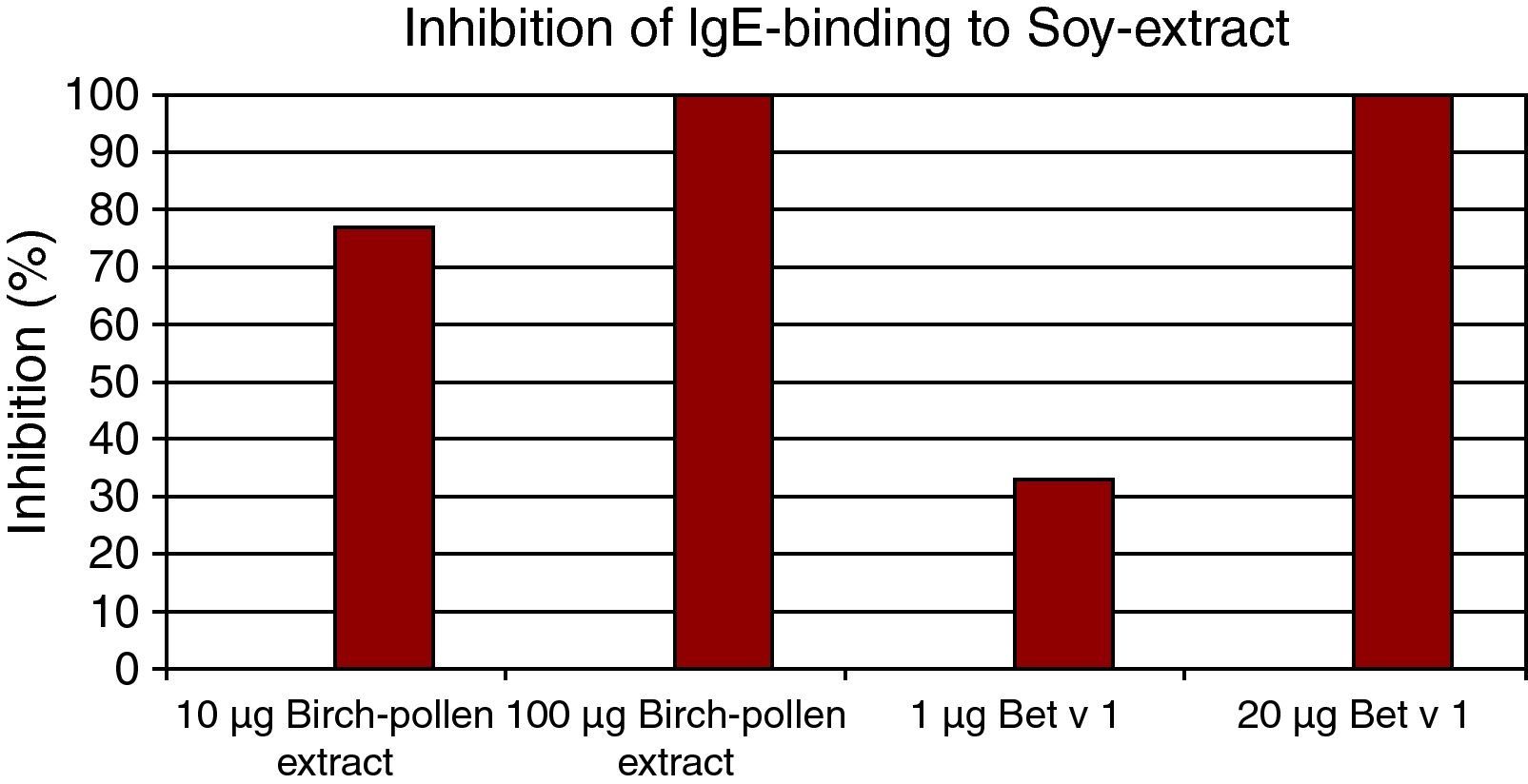

For ELISA inhibitions experiments, individual patients’ sera were pre-incubated with birch pollen or soy protein extracts, rBet v 1 or rGly m 4 at final concentrations of 1, 10, 20 and 100μg/ml were added to the soy or birch pollen protein extract and to the rBet v 1 or rGly m 4-coated wells. IgE-binding was detected as described above.

The skin prick test with commercial extracts showed positive results to birch pollen and the cross-reactive hazelnut, Candida albicans, dog, peanut, tomato, celery, but remained negative to soy extract. The total serum IgE was in normal range (92.3kU/l). Specific IgE against birch pollen (9.67kU/l, cut off 0.35kU/l) and cat dander (0.85kU/l) were elevated.

The patient's history suggested a clinically relevant birch pollen allergy resulting in the vernal rhinoconjunctivitis and although the skin and IgE tests to soy remained negative, we suspected a cross-reaction from the birch PR10 protein Bet v1 to its homologue in the soy bean Gly m4 that could be demonstrated with a commercially available in vitro assay with recombinant Gly m4 (1.04 kU/l).

To further affirm the hypothesis that the reactivity to soy relied only on the cross-reactivity with Bet v 1 and not a sensitisation to other soy components, we performed ELISA binding essays with Bet v1, Gly m4, Dau c 1 from carrot and Mal d 1 from apple. Only the patient's serum showed cross-reactivity with Gly m 4, while the serum of a birch pollen allergic control without soy allergy did not (Fig. 1).

In ELISA inhibition experiments we showed that soy bean extract (100μg), Gly m 4 (10μg) and Bet v 1(10μg) could inhibit IgE binding to birch pollen extract, and that Bet v 1 could also inhibit IgE binding to soy protein (Figs. 2,3).

We report a Bet v 1 sensitised patient with cross-reactivity to Gly m 4. Interestingly, the skin test with commercial soy extract for skin prick testing and the extract-based commercial IgE test remained negative in our patient. This observation parallels the finding of two other studies, which in birch pollen allergy-related soy allergy mediated by Gly m 4, the clinical diagnosis is hampered by quite low levels of Gly m 4 in commercial soybean extracts.1,2 Only the determination of sIgE against Gly m 4 proved the cross-reactivity in this patient.

Soybean is a clinically relevant food allergen and can induce severe allergic symptoms.3 So far, 16 IgE-binding allergenic components from soybean have been identified.2 Gly m 1 and Gly m 2 are inhalant allergens in occupational soybean allergy, Gly m 3 and Gly m 4 are known as birch- pollen related allergens, and the soybean major storage proteins Gly m 5 and Gly m 6 are potential diagnostic markers for severe allergic reactions.2 The prevalence of soybean allergy in the general population is still unknown.4 Mittag et al. in 2007 reported a prevalence of 10% among patients in Central Europe sensitised to birch pollen caused by cross-reactivity between Bet v 1 and its homologue in soy, Gly m 4. The allergenicity of Gly m 4 is very variable in different soy products and depends on the degree of food processing. Threshold doses for symptoms were shown to be highly variable (10mg to 50g) and did not show any correlation with the severity of induced symptoms.4 The highest amounts of Gly m 4 were measured in soy drinks and dietary powders, whereas Gly m 4 was hardly detectable in fermented soy products like tofu or soy sauce. Strong heating destroys the antigen-binding capacity of Gly m 4 totally, whereas low amounts of Gly m 4 could still be found in limited heated soy products1 in the same way as must have been the case in the initial anaphylactic reaction of our patient.

Interestingly, the commercial skin and extract based IgE was negative in our patient. This finding parallels the finding of two studies, which in birch pollen- related soy allergy through gly m 4, diagnosis is hampered by quite low levels of gly m 4 in commercial soybean extracts.1,2 Only the determination of sIgE against Gly m 4 proved the cross-reactivity in this patient.

In summary, we report the case of a patient suffering from vernal, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis to birch pollen. The anaphylaxis was caused by a cross-reaction to soy in the meat loaf. Probably, the broiling of the meat loaf was not sufficient to heat-denaturise the Gly m4. This case highlights that the intake of soy-containing products can cause severe allergic reactions in birch pollen allergic patients and that the patients should avoid the consumption of soy protein. In the case of false negative skin prick test and sIgE against soy extract the measurement of sIgE against Gly m 4 is required to ascertain the diagnosis.

Katharina Moritz was supported by an EU grant within the 6th framework program GA2LEN (global allergy and asthma European network) FOOD-CT-2004-506378.