There is little research in the Spanish paediatric population about the consumption of anti-asthmatic agents. The aim of this study was to describe the current pattern of anti-asthmatic drug prescription in the paediatric population from a region of Spain, using the prescribed daily dose as a unit of measurement.

MethodsWe analysed the requirements of R03 therapeutic subgroup (anti-asthmatic agents) in children less than 14 years of age in the Public Health System of Castilla y León from 2005 to 2010. Consumption data are presented in prescribed daily doses per thousand inhabitants per day (PDHD) and compared with defined daily doses per thousand inhabitants per day (DHD).

Results394 876 prescriptions of anti-asthmatics were given to a population of 1 580 229 persons/year. Bronchodilators, leukotriene receptor antagonists, single inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and long-acting β2-adrenergics associated with inhaled corticosteroids were the most commonly prescribed drugs: 7.5, 5.2, 4.9 and 2.2 PDHD, respectively. The maximum prescription of bronchodilators (15.9 PDHD/9.8 DHD) occurred in children under 12 months, with montelukast (8.9 PDHD/3.6 DHD) and single inhaled corticosteroids (7.9 PDHD/2.9 DHD) at one year of age.

ConclusionsBetween 2005 and 2010, children under four years received a high prescription of anti-asthmatic drugs. The use of maintenance therapy was poorly aligned with the recommendations of asthma guidelines. The PDHD was more accurate for measuring consumption than DHD, especially in younger children.

Asthma is the most prevalent chronic paediatric disease with effective treatment. Its prevalence in Spain is around 10%.1 There is little research in the Spanish paediatric population about the consumption of anti-asthmatic agents which reveals the current pattern of use.

Worldwide information about the prescription of anti-asthmatic drugs in children shows a high variability between and within each country, with this variability not being related to incidence and the conditions of the disease,2 as it is generally younger children who have a higher consumption of drugs.3–6

The results of studies on anti-asthmatic prescriptions in children are generally expressed in number and/or percentage of prescription for every drug3,5,6 or in number and/or percentage of children who have received any drug at a certain age.6–9 The WHO recommends the use of defined daily dose (DDD) for evaluating the consumption of drugs in adults. However, it is generally accepted that these units should not be applied in childhood because they are not specifically calculated for children for most approved drugs and it is not appropriate to use adult doses of consumption in paediatric studies because the results would be underestimated. Therefore, the WHO recommends paediatric studies to use prescribed daily dose (PDD) of active ingredients and compare them with the DDD for adults,10 and it was decided to follow such recommendations in this study. However, very few studies are expressed as DDD11,12 or PDD,13–17 and a limited number of active ingredients are analysed in these cases.

The aims of our study were to determine the prescription pattern of anti-asthmatic drugs (RO3 subgroup) in children less than 14 years old in the Public Health System of Castilla y Leon, during 2005–2010, and to assess the possible differences when using PDD or DDD as units of drug consumption.

Methods and populationPopulation and settingCastilla y Leon is a large region in the centre of Spain (94 225km2). It has 2 550 000 inhabitants, of whom 12% are children under the age of 14. The prevalence of asthma in the paediatric population in 2010 was 7.4% (from doctor diagnoses), with grass pollen being the allergen most frequently implicated in allergic asthma.

The prescription data were obtained from the Pharmacy Information System of the Public Health Service of Castilla y Leon (SACYL), which covers 96% of the population. Data came from the total computerised official prescriptions written between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2010 and dispensed in pharmacies. At the time of the study, only prescriptions from primary care were computerised (80% computerised and 20% issued manually). Prescriptions from primary care represented 94% of the total official requirements of Public Health System of this period, as hospital prescriptions only accounted for 6% of the total. Data correspond to the RO3 therapeutic subgroup (drugs for respiratory obstructive diseases) of the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification of WHO [ATC classification18]. The active ingredient and the age of the children were analysed for all prescriptions. Only electronic prescriptions were able to identify the patient's age. The patient identification data, the prescribing physician or the trademark used was not collected, in order to maintain the anonymity of those aspects.

The included population was children under 14 years old who had an individual health card (TSI) of Castilla y Leon between the years 2005 and 2010. The TSI identifies people who may personally receive national health care and official prescriptions. The paediatric population data for each age (0–13 years) were obtained from the Technical Department of the SACYL.

Units of measurementThe main analysis unit was the prescribed daily dose (PDD), which is the usual recommended average daily dose of a given drug for its main indication. As there are no defined PDD for anti-asthmatic drugs in paediatric cases, they were elaborated taking into account the age or body weight dose recommended in the data sheet of each drug and the main guidelines for asthma in childhood. PDD was determined for 26 active ingredients with 59 different concentrations and pharmaceutical forms (inhaler, syrup, tablets, etc.). In cases where the PDD was calculated per kg body weight per day, tables were used representing the weight of the current Spanish child population.19 In other drugs, PDD was estimated by age sections. On the other hand, regarding inhaled corticosteroids, single or in combination, the PDD was calculated for each concentration of inhaler device and each age and it was concluded that the PDD was one inhalation every 12h, with the exception of formats of 50mcg of budesonide, beclomethasone and fluticasone, in which two inhalations every 12h was considered (usually the recommended dose). Online supplementary material for the calculation of the PDD is provided: Appendix I.

Results are shown in prescribed daily dose per thousand inhabitants per day (PDHD). The PDHD represents the average prescribed daily dose every day to 1000 people exposed. The PDHD was calculated for each active ingredient, raw and age-adjusted, by the direct adjust method [standard population20], using all children from Castilla y Leon with a TSI card and aged 0–13 years as the reference population.

The results in defined daily doses per 1000 inhabitants per day (DHD) have also been added to allow comparison of both units for all ages and to future comparisons with other studies. We have used the DDD values proposed by the WHO for each active ingredient.18

SPSSv15 and Excel sheets were used for statistical analyses.

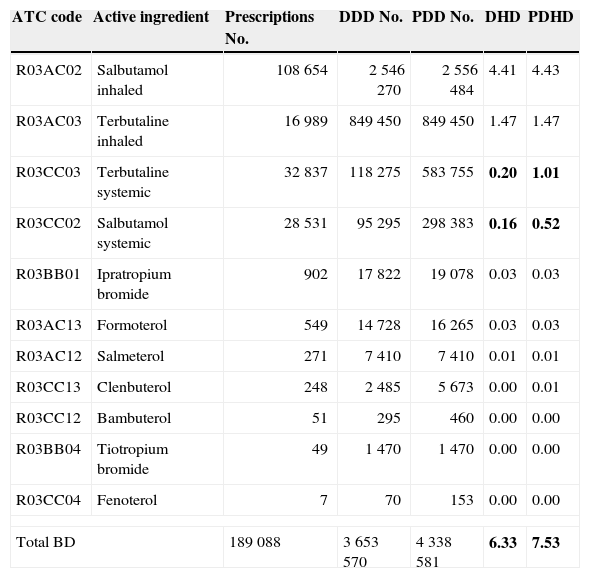

ResultsDuring the six-year study, 394 876 prescriptions of anti-asthmatic drugs were issued to an at risk population of 1 580 229 person/year. Among them, 82% were prescribed by paediatricians. Bronchodilators (BD) were the most consumed drug (7.5 PDHD), mainly in inhaled form (5 PDHD). With respect to maintenance therapy, leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRA) were the most prescribed subgroup (5.2 PDHD), followed by single inhaled corticosteroids (ICS: 4.7 PDHD), with inhaled corticosteroids associated with long-acting beta-agonists being the least common (LABA-ICS: 2.2 PDHD) (see Tables 1–3).

Total results bronchodilators (BD): No. prescriptions, DDD, PDD, DHD and PDHD.

| ATC code | Active ingredient | Prescriptions No. | DDD No. | PDD No. | DHD | PDHD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R03AC02 | Salbutamol inhaled | 108 654 | 2 546 270 | 2 556 484 | 4.41 | 4.43 |

| R03AC03 | Terbutaline inhaled | 16 989 | 849 450 | 849 450 | 1.47 | 1.47 |

| R03CC03 | Terbutaline systemic | 32 837 | 118 275 | 583 755 | 0.20 | 1.01 |

| R03CC02 | Salbutamol systemic | 28 531 | 95 295 | 298 383 | 0.16 | 0.52 |

| R03BB01 | Ipratropium bromide | 902 | 17 822 | 19 078 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| R03AC13 | Formoterol | 549 | 14 728 | 16 265 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| R03AC12 | Salmeterol | 271 | 7 410 | 7 410 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| R03CC13 | Clenbuterol | 248 | 2 485 | 5 673 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| R03CC12 | Bambuterol | 51 | 295 | 460 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| R03BB04 | Tiotropium bromide | 49 | 1 470 | 1 470 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| R03CC04 | Fenoterol | 7 | 70 | 153 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total BD | 189 088 | 3 653 570 | 4 338 581 | 6.33 | 7.53 | |

In bold type are the major discrepancies between the two current measurement units of use (PDHD and DHD).

Total results maintenance therapy: No. prescriptions, DDD, PDD, DHD and PDHD.

| ATC code | Active ingredient | Prescriptions No. | DDD No. | PDD No. | DHD | PDHD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R03AK06 | Salmeterol+Fluticasone | 19 307 | 579 210 | 930 480 | 1.00 | 1.61 |

| R03AK07 | Formoterol+Budesonide | 5 840 | 175 200 | 341 400 | 0.30 | 0.59 |

| R03AK04 | Combined salbutamol | 66 | 2 992 | 2 992 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total combined corticosteroids | 25 213 | 757 402 | 1 274 872 | 1.30 | 2.20 | |

| R03BA02 | Budesonide inhaled aerosoL | 25 971 | 647 350 | 1 523 050 | 1.09 | 2.64 |

| R03BA05 | Fluticasone inhaled aerosol | 35 111 | 467 430 | 1 138 290 | 0.81 | 1.97 |

| R03BA01 | Beclometasone inhaled aerosol | 807 | 15 106 | 45 600 | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| R03BA02 | Budesonide inhaled solution | 11 563 | 33 059 | 32 065 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| R03BA08 | Ciclesonide inhaled aerosol | 4 | 240 | 240 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total inhaled corticosteroids | 73 456 | 1 163 185 | 2 739 245 | 1.99 | 4.74 | |

| R03BC03 | Nedocromil inhaled | 271 | 7 588 | 7 588 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| R03BC01 | Cromoglicic acid inhaled aerosol | 63 | 324 | 796 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total chromones | 334 | 7 912 | 8 384 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| R03DC03 | Montelukast | 106 706 | 1 377 762 | 2 987 768 | 2.39 | 5.18 |

| R03DC01 | Zafirlukast | 22 | 660 | 660 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total antileukotrienes | 106 728 | 1 37 422 | 2 988 428 | 2.39 | 5.18 | |

| R03DA04 | Theophilline | 56 | 390 | 522 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| R03DA06 | Etamiphilline | 1 | 6 | 19 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total xanthines | 57 | 396 | 541 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Total maintenance therapy | 205 788 | 3 307 317 | 7 001 470 | 5.70 | 12.14 | |

In bold type are the major discrepancies between the two current measurement units of use (PDHD and DHD).

Prescriptions percentages, DHD and PDHD of main subgroups of anti-asthmatics agents.

| ATC code | Antiasthmatic subgroup | Prescriptions No. | Prescriptions % | DHD | % DHD | PDHD | % PDHD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R03AC, R03BB, R03CC | Bronchodilators | 189 088 | 47.88 | 6.33 | 52.32 | 7.53 | 38.82 |

| R03DC | Antileukotrienes | 106 728 | 27.02 | 2.39 | 19.81 | 5.18 | 25.85 |

| R03BA | Inhaled corticosteroids | 73 456 | 18.60 | 1.99 | 16.91 | 4.74 | 24.25 |

| R03AK | Combined corticosteroids | 25 213 | 6.38 | 1.31 | 10.86 | 2.20 | 11.02 |

| R03BC | Chromones | 334 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| R03DA | Xantinas | 57 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total R03 | 394 876 | 99.97 | 12.03 | 99.98 | 19.66 | 99.99 | |

In bold type are the major discrepancies between the two current measurement units of use (PDHD and DHD).

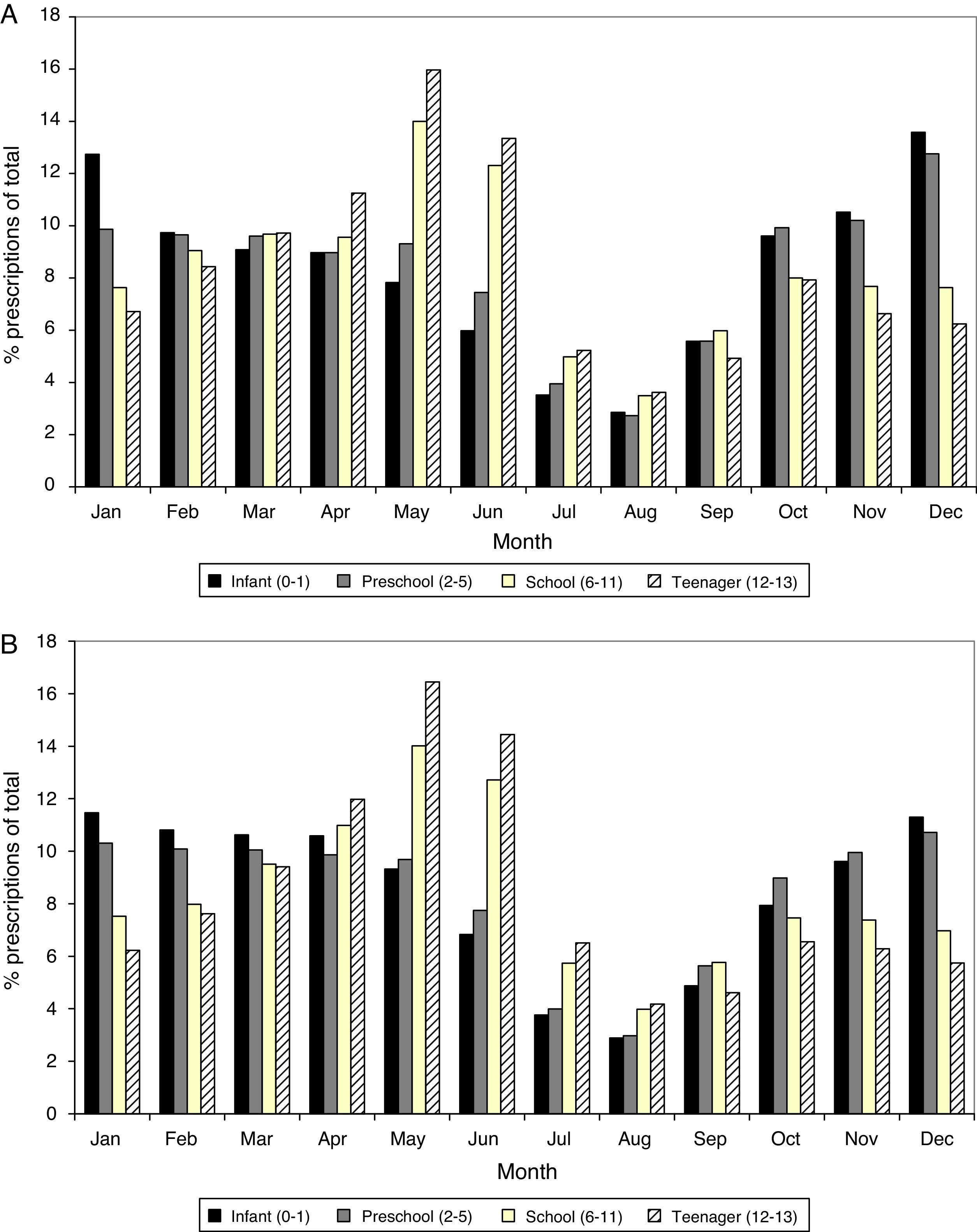

Anti-asthmatic prescriptions were twice as frequent from October to June compared to July to September, for both bronchodilators and maintenance therapy. Monthly variations were also observed according to age: prescriptions in children and adolescents occurred mainly in spring, while these predominated in autumn and winter in infants and children of preschool age (Fig. 1).

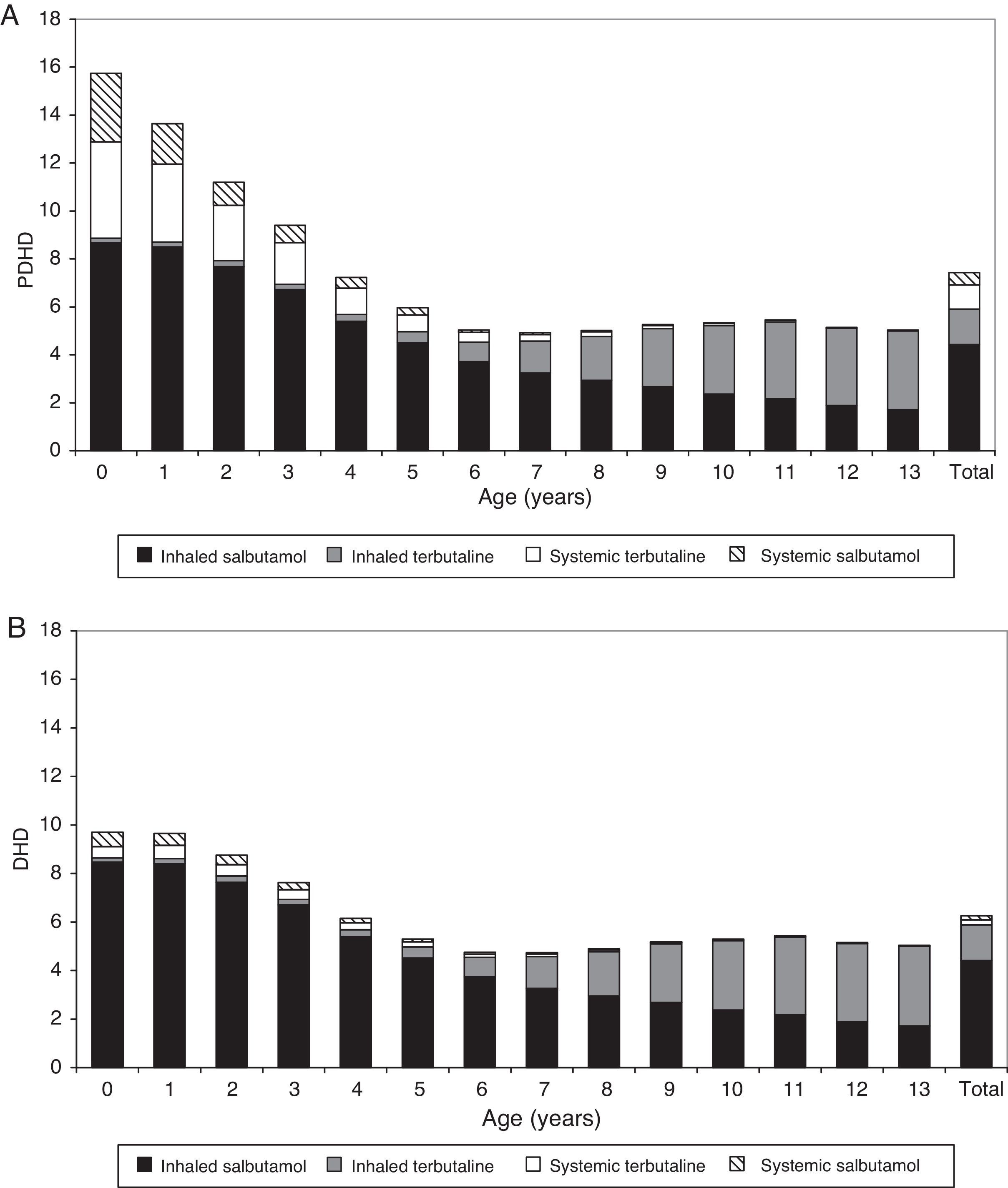

The prescription of anti-asthmatic drugs was higher in younger children, especially those below 4 years old. The peak bronchodilator consumption occurred in the first 2 years of age and its use from 6 to 14 years of age was much lower and more stable. Evaluating by PDHD, children under 1 year received 3 times more bronchodilators (15.9 PDHD) than children older than 6 years (5.1–5.6 PDHD); those aged 1 year received 2.5 times more (13.7 PDHD) and children aged 2–3 years, twice as many (9.5–11.3 PDHD). At all ages, inhaled bronchodilators were predominant (6 PDHD inhaled, 1.5 PDHD in oral presentation), but the oral presentation was much more commonly prescribed in the first 4 years than in later ages (see table E3 in supplementary material online).

Measured by DHD: Consumption intensity was 5.9 DHD for inhaled BD and 0.4 DHD for the oral presentation; systemic bronchodilators were also more frequently consumed in younger patients, but the systemic use was much higher in PDHD than expressed in DHD. After six years of age, the consumption intensity showed no difference when it was determined by PDHD or by DHD, because inhaled bronchodilators were the most frequently prescribed. Fig. 2 shows the difference in consumption quantification using both units, PDHD and DHD.

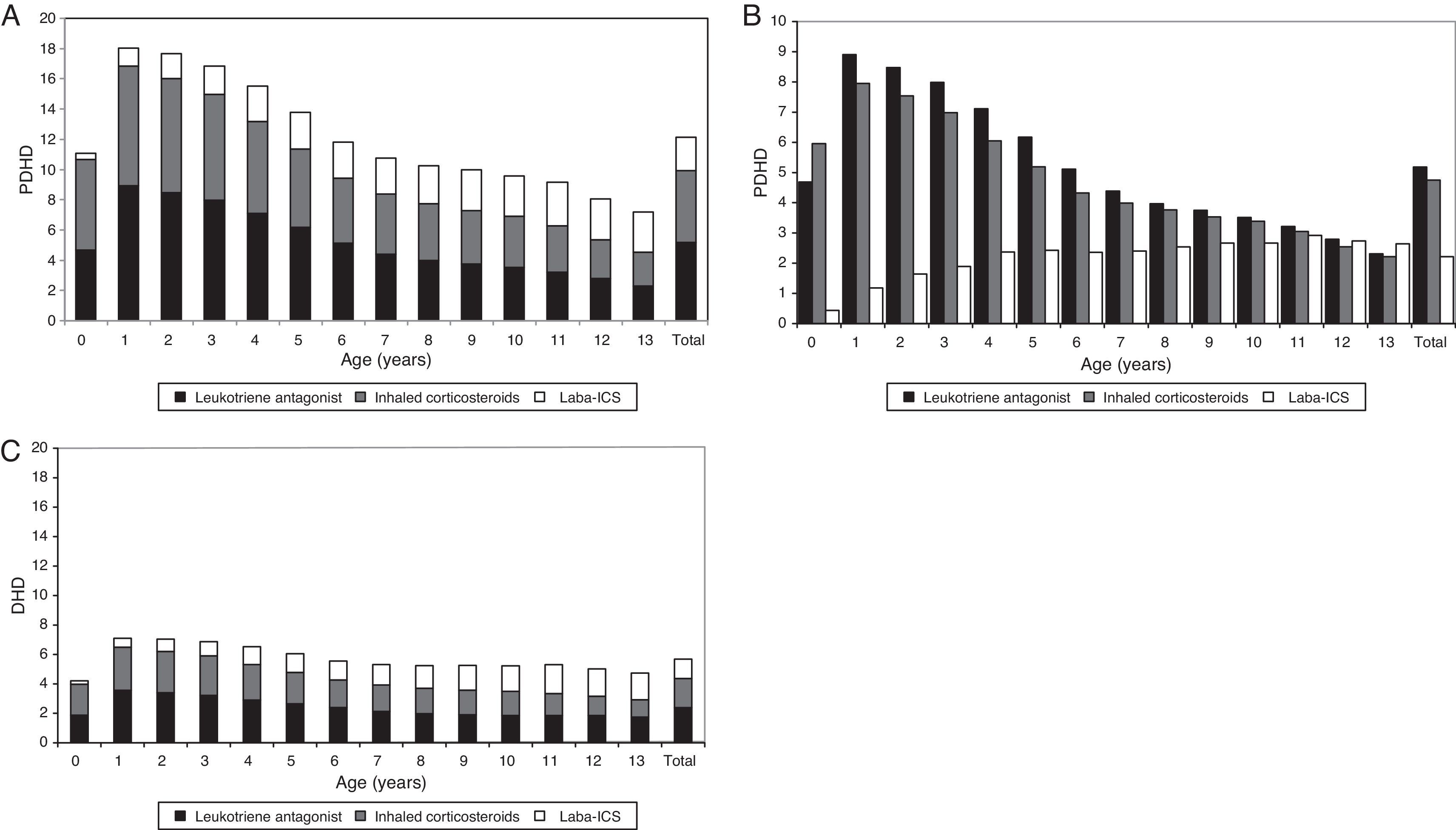

Regarding maintenance therapy, ALT (almost exclusively montelukast) were the most frequently prescribed drug throughout all age groups, except in infants under 12 months, in which they were outweighed by ICS, and in 13-year old adolescents, in which LABA-ICS was the preferred choice. The prescription of LABA-ICS combinations increased progressively with age, but they were prescribed from the first months of life and 18% of the total were consumed by children below four years. Chromones and xanthine had a very low consumption at all ages.

Using PDHD units, ICS and ALT were provided in all ages with a parallel frequency plot, but this was much greater in children under six years. The highest consumption of ALT (8.9 PDHD/3.6 DHD) and ICS (7.9 PDHD/2.9 DHD) occurred at one year of age and the peak of LABA-ICS (2.9 PDHD/2 DHD) at 11 years of age. The intensity of consumption measured by DHD was similar at any age, and half that measured by PDHD, except in children under one year, where it was four times lower in DHD than in PDHD (Fig. 3).

Prescription of major maintenance therapy by age, comparison of the intensity of use according to the measuring units. (A) PDHD (aggregated data of maintenance therapy), (B) PDHD (each subgroup of maintenance therapy separately), (C) DHD. LABA-ICS: long-acting β2 adrenergic associated with inhaled corticosteroids. PDHD: Prescribed daily doses per thousand inhabitants per day. DHD: Defined daily doses per thousand inhabitants per day.

The intensity of consumption over 2005–2010 had discrete annual variations. The use of short-acting inhaled bronchodilators increased slightly (in 2005: 5.7 PDHD, in 2010: 6.8 PDHD) and the main ingredients of maintenance therapy remaining almost constant.

DiscussionKey findingsThis study analysed the paediatric prescription of anti-asthmatic agents by age in a relevant population sample and provided current information regarding use in a Spanish region. An excessive prescription was observed in younger children, with the significant use of systemic bronchodilators and some subgroups of maintenance therapy that are inconsistent with the recommendations of current asthma guidelines and treatment protocols of secondary wheezing to viral infections. The study also compared the intensity of consumption offered by PDHD and DHD units, showing that DHD underestimates the results at all ages, especially in young children.

InterpretationThe high prescription of anti-asthmatic drugs in young children has already been observed in other international studies conducted in the general paediatric population. In these, it also appears that children under two years received more anti-asthmatic agents,3–6,22,23 although the overall prevalence and age varied among countries. This fact is justified on the one hand by the high frequency of viral respiratory infections that occur with bronchial obstruction in younger children. On the other hand, because the differential diagnosis of asthma is not easy under four years, this could lead to the use of anti-asthmatic drugs as a therapeutic diagnostic test.

Regarding the type of drug used in this study, the bronchodilators were the most prescribed, and were highly consumed in children less than two years old. Also, other drugs were prescribed (in descending order): leukotriene receptor antagonists (ALT), single inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and inhaled corticosteroids associated to long-acting beta-agonists (LABA-ICS). The use LABA-ICS in children under four years old was remarkable. This is an issue of concern due to the increased possibility of adverse effects in this age subgroup24,25 and because prescriptions were made outside the authorised conditions of use (off-label). The prescription pattern found does not fit the recommendations of current asthma guidelines or the therapeutic protocols of related diseases, and is also not justified given the severity of asthma that is currently reported in Spain.7,8,26

Regarding the type of drug used in other countries, the prescription of bronchodilators decreases with age. The consumption of inhaled corticosteroids is highest in pre-school and school children, except in Italy,3,6 with predominance in infants under one year. The prescription of LABA-ICS is not frequently measured, but also increases with age.6,12,16,22,23 In relation to maintenance treatment in other countries, inhaled corticosteroids as a single agent is generally the most prescribed subgroup, as recommended in the guidelines, followed by leukotriene receptor antagonists in second or third place. Although the prescription of montelukast is high in some countries2,9,11,23 and almost absent in others,6,12,17,27 which may be related to the differences at the time of the study, the population age or the prescription control has specific rules in each country.

The high prescription of montelukast that occurred in our study for all ages and which has been the most widely used drug controller, probably has a multifactorial explanation, but is closely related to the strong trade promotion and the influence of the article published by Bisgaard et al.28 claiming its beneficial effect on the post-bronchiolitis symptoms due to respiratory syncytial viruses. However, the findings were not confirmed by the author himself in a later and more extensive study.29 Other contributing factors may be related to the use of montelukast as a monotherapy controller or its use for other problems such as allergic rhinitis or atopic eczema. Also, the initiation of maintenance therapy with more than one drug (montelukast and other more), or the supposed absence of adverse effects [an issue questioned in post-marketing studies30], may have an influence.

Another contribution of our study has been the use of the prescribed daily dose (PDD) as a consumption unit and its comparison with defined daily dose (DDD) as it is recommended by the WHO to use in paediatric studies. We have not chosen the rate of prescriptions as unit of consumption because the size of the package and their contents vary between and within countries and although it is a unit widely used in other studies it is not very accurate. On the other hand the DDD is the consumer unit of measurement currently used in the Spanish Health Service, both in children and in general practice, to assess consumption and set targets for prescribing quality; thus, there are several recent publications in paediatric populations using DDD/DHD.31,32 We have decided to know the differences in the quantification of consumption between PDD and DDD. What we found was that the DDD/DHD underestimates the consumption in children, and more severely, the lower the age and/or the body weight: the systemic use of BD was four times lower in the first two years in DDD/DHD than in PDD/PDHD. In maintenance therapy, the use of the three major subgroups was half or almost half in DDD/DHD that in PDD/PDHD throughout the first 14 years of life (see Figs. 2 and 3). We cannot compare the information obtained in other studies, however, as no other has so far measured consumption using the two types of units.

The above comments highlight the difficulties and the limitations of using DDD/DHD units in children, since they underestimate drug consumption for almost all ages, except for inhaled bronchodilators, whose doses are independent of age or weight. Although the DDD/DHD is a technical unit of measurement that is often used for comparing consumption between countries or regions, at different periods of time, such comparisons could be made with data from PDD/PDHD, which would approximate more to actual consumption in childhood.

From the results obtained, we propose to use PDD as the consumption unit of the active agent and PDHD (prescribed daily doses per 1000 inhabitants per day) to compare figures in different paediatric populations at a determined time, or alternatively to apply a correction factor according to age to the adult DDD figures (see supplementary material online; Appendix I).

Limitations and strengthsThe first limitation of this study was the lack of connection between the pharmacist consumer database and the patient's medical record, so we could not determine the actual dosage and had to estimate the doses of each drug by age, body weight or concentration of each active ingredient. Therefore, the PDD calculated are theoretical doses. Nevertheless, the presumption is probably very close to the actual doses prescribed by physicians, given the information sources used for the calculations, which are the most frequently used by Spanish paediatricians.33 For the same reason it is not possible to estimate the prevalence of anti-asthmatic prescriptions because the data base has no information to identify each patient and their prescriptions. Furthermore the prevalence of anti-asthmatic prescription is not a valid measurement of the amount of exposure to anti-asthmatic agents, because it does not allow to know whether these children actually have used drugs or for how long or the treatment intensity.

Another limitation, common to studies using pharmacy dispensing databases, is the absence of information on clinical entities for which the drugs were prescribed, their severity and the type of therapy based on this, as well as the duration of drug use. Nevertheless, these kinds of databases provide interesting and extensive information on the prescription pattern.

Finally, the analysed prescriptions correspond to those written by primary care physicians, belonging to the Public Health System and dispensed in pharmacies, to children under 14 years. It does not include hospital prescriptions, as already mentioned, or prescriptions made in private clinics [10–15% of paediatric consultations in Spain21]. Also, anti-asthmatic agents purchased without a medical prescription [2.5% (21) were not included]. In short, we estimate the data collected represents 65% of the anti-asthmatic drugs prescribed in Castilla y León during the study period. However, we have no reason to think that the requirements not analysed have a different pattern to the one found, since most of them were conducted by the same physicians.

The main strengths of this study are its large population size and the consumption unit of measurement used.

In conclusion, the analysed data allowed us to determine the consumption pattern of anti-asthmatic agents in a very large paediatric population from a Spanish region in a recent time period (2005–2010). They reveal a high prescription in younger children and therapeutic inadequacies given current recommendations for the treatment of asthma and related diseases. It also showed that the defined daily dose (DDD) is a less appropriate unit of measurement of consumption in children than prescribed daily dose (PDD). These results demand medical professionals and health authorities to reflect as they indicate that there is an opportunity for improvement in the use of anti-asthmatic drugs as well as in the analysis of consumption.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. They have neither sponsors nor grants.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

The authors thank Judith Ceruelo, Julia Rodríguez and Alejandra Ortiz, Pharmaceutical from Technical Management Sacyl Pharmacy; they also thank Marcelino Galindo, from the Technical Department of Primary Care of Sacyl, for their valuable support.