This study aimed to assess the regular use of long-term asthma-control medication and to determine inhaler techniques in asthmatic children.

MethodsThe study was conducted on asthmatic children aged 6–18 years. Information on rescue and controller medications was given and the proper inhalation technique was demonstrated. One month later, patients and parents were asked to answer a questionnaire on drug use and to demonstrate their inhaler techniques.

ResultsOne hundred children and/or their parents were interviewed for the study. All of the patients identified long-term asthma-control medications while quick-relief asthma medications were identified by 93% of the patients. Of the patients, 34% described the dose of their quick-relief medication correctly. All steps in the inhalation technique were correctly carried out by 60.6% of patients using a metered-dose inhaler (MDI), 80% of patients using a Turbuhaler, and 58% of patients using a capsule-based dry-powder inhaler (DPI). Of the participants, 73% reported regular use of long-term asthma-control medications. While the mean age of the patients regularly using long-term asthma medications was 9.05±2.5 years, that of patients not compliant with the regular treatment was 10.29±3.26 years (p=0.04). The most common reason for irregular drug use was forgetting to take the drug.

ConclusionAdherence to long-term asthma-control medications tends to be better in younger patients. Since the most common cause of irregular drug use is forgetting to take the drug, repeated training is necessary to ensure asthma control and the successful treatment of asthmatic children.

Asthma is one of the most common chronic diseases in childhood1 and has increased, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.2 The aim of asthma treatment is to manage the clinical control of the disease in terms of symptoms, pulmonary function, and prevention of asthma exacerbations. Asthma guidelines advise that children with persistent asthma should use their asthma-control medications regularly for ideal asthma control; yet, despite current treatment guidelines and medications, many children suffer from asthma exacerbations and persistent symptoms.3,4 Common factors leading to failure to achieve or loss of asthma control are environmental exposure, comorbid conditions, cost, lack of insurance, and lack of access to healthcare, poor adherence to management plans and improper inhaler device technique—the latter two being the most important reasons.5,6

Non-adherence to treatment for chronic diseases in children is common.7–9 Adherence to control medications in asthmatic children is reported to be 50% or less.10 Non-adherence and/or poor adherence are associated with morbidity and mortality in asthmatic patients.11 Many behavioral and treatment factors have been shown to contribute to non-adherence. Intentional non-adherence is due to a lack of motivation; unintentional non-adherence is due to a lack of understanding the prescription or the usage of the medicine or due to forgetting to take the medicine.3,12,13 Non-adherence can be handled with successful doctor–patient communication and educational interventions.14 Asthma-treatment regimens contain more than one drug with different effects, and, since different devices may be used to administer the drugs, patients need to be familiar with the types of drugs and be competent in using the necessary devices for adherence to their asthma-treatment regimen.15 The purpose of this study was to assess the regular use of long-term asthma-control medications and to determine inhaler techniques in asthmatic children.

MethodsStudy subjectsChildren with physician-diagnosed persistent asthma, aged 6–18 years, and who had visited the pediatric allergy department during the previous three months were included the study. They were prescribed long-term asthma-control medications to be used for at least three months, and quick-relief medications as needed. Children with intermittent asthma or with other respiratory diseases, such as cystic fibrosis, were excluded from the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all parents with the assent of children over seven years of age. The Ethics Review Committee at the Trakya University Medical Faculty approved the study.

The medications compliance rate and use of medications with the correct technique in asthmatic patients were reported between 30 and 70%.11,16 The sample size was calculated as 97 based on an assumed rate of 50%, with a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 10%. However, we determined to include 100 patients, considering possible missing data. The following formula was used in the calculation of the sample size.17n=(Z∝/22*p*q)/d2; Zα/2=1.96, p=0.5, q=0.5, and d=0.1.

Study designThis prospective observational study was performed in the outpatient clinic of a pediatric allergy department in a hospital in Edirne, Turkey. The subjects were consecutively enrolled if they had met the inclusion criteria. The age, gender, and asthma-control levels, determined according to the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines,3 of the patients were recorded. Oral and written information on reliever and controller medications, including the name, dose, administration route, and when to use, were given. Additionally, proper inhalation techniques were instructed to children accompanied by the parent before enrollment to study in 20min. All the data was collected and the instructions were given by pediatric allergy fellows (C.C: Can Ceren; A.E: Akkelle Emre; G.O.P: Gokmirza Ozdemir Pınar). One month later, the patients and parents were invited to answer a questionnaire in order to check their understanding of prophylactic and reliever medications and their adherence to their controller prescriptions.

QuestionnairePediatric allergists from the study team (C.C, A.E, G.O.P) completed questionnaires via face‐to‐face interviews with patients and parents to check understanding and compliance with prophylactic and reliever prescriptions. The questionnaire was developed based on previously published papers with slight modifications (Appendix 1, Supplementary Material).16,18

Parents and children were then asked to demonstrate their inhaler techniques for the metered-dose inhaler (MDI), the Turbuhaler, and the capsule-based dry-powder inhaler (DPI). Their inhaler techniques were checked by pediatric allergy fellows on the questionnaire form (Appendix 1, Supplementary Material).

For MDI/spacer combinations, seven items were questioned involving: shaking the MDI and removing the cap, the correct connection of the spacer device and MDI, placing the facemask over the nose and mouth and forming a seal, activation of the MDI, taking five or six deep and slow breaths, rinsing the mouth when the process is finished, and washing the spacer intermittently. For the Turbuhaler, four items were questioned: removing the cap; twisting the colored grip of the Turbuhaler as far as it goes, then twisting it all the way back and hearing a “click”; taking a deep breath, putting the mouthpiece between teeth, and closing lips around it; breathing in forcefully and deeply through mouth and holding the breath for 10s; and rinsing the mouth when the process was completed. For the capsule-based DPI, five items were questioned: placing the capsule on the device and perforating it; taking a deep breath and exhaling to residual volume; taking a quick and deep breath and holding it for 10s; checking the capsule to see if any drug is left; and rinsing the mouth when the process is complete.

Statistical analysisNumerical results are expressed as mean±standard deviation, categorical results as a number (percentage). Normal distribution was tested by the one-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Differences between groups were assessed using the Student’s t-test for normal and the Mann–Whitney U test for non-normal data distribution. The chi-square test was used to compare the differences of categorical variables between the groups. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

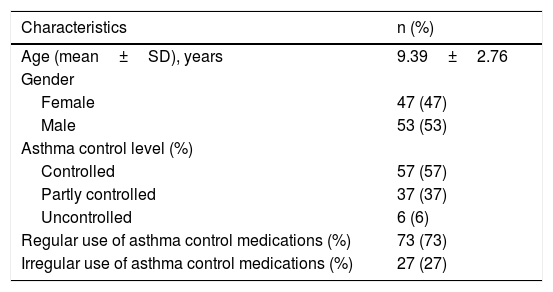

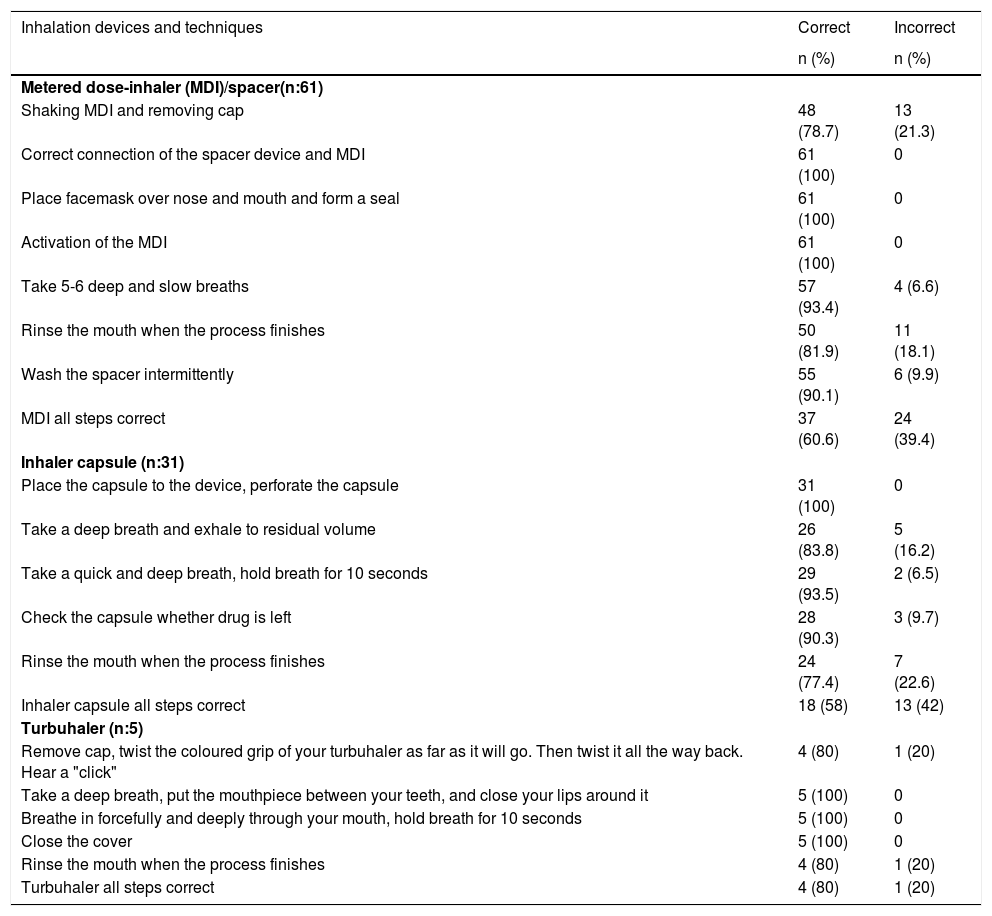

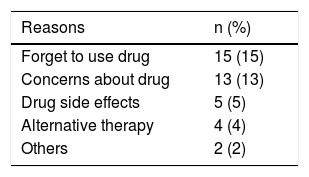

ResultsA total of 100 patients were included in the study and all patients completed the study. There was no drop out in the study. The demographic characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. Of the patients, 47% were female. Pharmaceutical forms of the long-term asthma-control medications are shown in Table 2. All of the patients identified long-term asthma-control medications correctly and 93% of the cases described the dose accurately. When they were asked about quick-relief asthma medications, 62% of the patients reported salbutamol, 28% terbutaline, and 1% inhaled steroids as their quick-relief medication, while 9% of the patients did not know the name of their medication. Of the patients, 34% described the dose of their quick-relief medication correctly (Table 3). All the steps of the inhalation technique were correctly carried out by 60.6% of the patients using the MDI; 80% using the Turbuhaler; and 58% using the capsule-based DPI. The common mistakes were not shaking the inhaler and/or removing the cap while using the MDI (21.3%); not loading a dose while using the Turbuhaler (20%); and not rinsing the mouth after the process for the MDI (18.1%), the Turbuhaler (20%), and the capsule-based DPI (22.6%). The correct and incorrect use of the inhalation devices and techniques are shown in Table 4. Out of the 100 patients, 73% reported that they were using long-term asthma-control medications regularly. While the mean age of patients regularly using long-term asthma medications was 9.05±2.5 years, the mean age of patients not compliant with regular treatment was 10.29±3.26 years (p=0.04). Regular use of long-term asthma-control medications did not differ between genders (p=0.88). Of the participants, 77% with controlled, 67.5% with partly controlled, and 66.6% with uncontrolled asthma reported that they were using long-term asthma-control medications regularly. There was no difference in regular drug use between the groups regarding the level of asthma control (p=0.55). The regular use of long-term asthma-control medications did not differ between drugs given by mouth or inhalation (p=0.34). The number of drugs (p=0.49) had no effect on asthma adherence. The most common reason for irregular drug use was forgetting to take the drug. The reasons for irregular drug use are shown in Table 5.

Demographic characteristics of the patients.

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD), years | 9.39±2.76 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 47 (47) |

| Male | 53 (53) |

| Asthma control level (%) | |

| Controlled | 57 (57) |

| Partly controlled | 37 (37) |

| Uncontrolled | 6 (6) |

| Regular use of asthma control medications (%) | 73 (73) |

| Irregular use of asthma control medications (%) | 27 (27) |

The correct use of inhalation devices and techniques in patients.

| Inhalation devices and techniques | Correct | Incorrect |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Metered dose-inhaler (MDI)/spacer(n:61) | ||

| Shaking MDI and removing cap | 48 (78.7) | 13 (21.3) |

| Correct connection of the spacer device and MDI | 61 (100) | 0 |

| Place facemask over nose and mouth and form a seal | 61 (100) | 0 |

| Activation of the MDI | 61 (100) | 0 |

| Take 5-6 deep and slow breaths | 57 (93.4) | 4 (6.6) |

| Rinse the mouth when the process finishes | 50 (81.9) | 11 (18.1) |

| Wash the spacer intermittently | 55 (90.1) | 6 (9.9) |

| MDI all steps correct | 37 (60.6) | 24 (39.4) |

| Inhaler capsule (n:31) | ||

| Place the capsule to the device, perforate the capsule | 31 (100) | 0 |

| Take a deep breath and exhale to residual volume | 26 (83.8) | 5 (16.2) |

| Take a quick and deep breath, hold breath for 10 seconds | 29 (93.5) | 2 (6.5) |

| Check the capsule whether drug is left | 28 (90.3) | 3 (9.7) |

| Rinse the mouth when the process finishes | 24 (77.4) | 7 (22.6) |

| Inhaler capsule all steps correct | 18 (58) | 13 (42) |

| Turbuhaler (n:5) | ||

| Remove cap, twist the coloured grip of your turbuhaler as far as it will go. Then twist it all the way back. Hear a "click" | 4 (80) | 1 (20) |

| Take a deep breath, put the mouthpiece between your teeth, and close your lips around it | 5 (100) | 0 |

| Breathe in forcefully and deeply through your mouth, hold breath for 10 seconds | 5 (100) | 0 |

| Close the cover | 5 (100) | 0 |

| Rinse the mouth when the process finishes | 4 (80) | 1 (20) |

| Turbuhaler all steps correct | 4 (80) | 1 (20) |

Current treatments for asthma provide effective long-term control of symptoms. However, poor adherence poses a significant obstacle in controlling asthma symptoms.19 Most asthma regimens include medications with different therapeutic modes of action and a number of different medication-delivery devices. To effectively participate in their asthma management, patients need to recognize each of their medication types, adhere to their treatment regimen, and be proficient in using the required delivery devices.15

In a pilot study in rural Australia, 75.9% of participants used preventer medication; the remaining 24.1% used reliever medication only. Of those using preventer medication, 82.5% distinguished their preventer medicine.15 In our study, all of the patients identified their long-term asthma-control medications and almost all of them described the dose correctly. While 90% of them identified quick-relief asthma medications, only 34% described the dose correctly. Quick-relief asthma medications were thus more neglected.

Poor inhalation technique is common among asthmatic children. In one study, 132 school children were evaluated, and their adherence to inhalation therapy was reported as 17.4%. None of the children were able to perform all stages of their inhaler technique correctly. For the MDI group, the most difficult skills seemed to be the progressive inhalation of the medicine slowly and deeply and the need to hold their breath for a count of 10. Children using a dry-powder inhaler encountered similar difficulties, including inhaling the medicine deeply and forcefully, exhaling to residual volume, and holding their breath for a count of 10.20 Boccuti et al.21 evaluated the inhalation technique using an MDI with three different spacer devices in 7–17-year-old asthmatic children. For both groups, the most difficult skills were shaking the canister at least three times before using it, exhaling before inhaling the medicine, inhaling the medicine slowly and deeply through the mouth, and breath-holding for a count of five. Kamps et al.18 reported that children who received comprehensive inhalation training with repeated inhalation technical checks were more likely to perform all the necessary steps correctly than those following single-session education. In our study, the adequate inhaler technique was evaluated for the different forms of inhaler devices. The common mistakes were not shaking the inhaler and removing the cap while using the MDI, not loading a dose while using the Turbuhaler, and not rinsing the mouth after the process for the MDI, the Turbuhaler, and the capsule-based DPI.

Adherence to asthma medication regimens tends to be very poor, with the reported rates of non-adherence ranging from 30% to 70%.10 Ménard et al.22 investigated adherence to asthma-control medications in 103 children aged 2–12 years. Nearly half of the patients had low adherence. In Koster et al.’s study,23 low adherence was reported by 54.7% of 170 parents of eight-year-old asthmatic children. Basharat et al.19 assessed adherence to asthma treatment and its association with asthma control in children. A significant association was found between well-controlled asthma and a high-adherence level. In our study, 73% of the patients reported taking their asthma-control medications regularly. There was no difference between the groups regarding the level of asthma control and regular drug use. From these results, we interpret that not only regular drug use, but also other factors such as environmental, may be related to the level of asthma control. Klok et al.24 found that children with poor adherence had lower levels of asthma control. According to their study, adherence was not found to be related to the children’s age. Our study results show that age was the most important factor affecting regular use of asthma-control medications; however, adherence to long-term asthma-control medications was better in younger patients. Further, when the parents’ belief that their child needs medication overbalances their concerns about the medication, adherence seems to be higher.18 Non-adherence to management regimens peaks in adolescence, along with poor asthma control and related morbidity.24 This can be explained by the fact that adolescent children are partially resistant to parental control. We think that children have more effective asthma treatment when it is under parental control. Stempel et al.25 reported similar adherence profiles with fluticasone and montelukast, fluticasone alone, and montelukast alone. However, in our study, montelukast was used alone in just 3% of patients and combined in half of the patients. Neither the inhaler device nor the number of medications was found to have an effect on regular use of long-term asthma-control medications.

There are various factors associated with non-adherence to asthma therapy. Medication-related factors include difficulties with inhaler devices, complex treatment regimens, and the side effects of drugs. Some studies have shown that adherence to drugs given by mouth is higher compared with inhaled medications in asthmatic children. In our study, however, there was no difference between drugs administered orally and inhaled drugs in the regular use of long-term asthma control drugs.26–28

Factors unrelated to medications include the underestimation of severity and forgetfulness.3 Forgetting is the most commonly reported cause of patients not taking medication.15,19,29,30 In our study, many causes of non-adherence were detected, such as forgetting to take the drug, concerns about the drug, using alternative therapy, and difficulty with multi-drug use. The most common reason for irregular drug use was forgetting to take the drug. We considered that forgetfulness may be associated with a low or lack of treatment motivation in our patients.

The limitation of our study is that we used questionnaires to assess our patients’ understanding of their asthma medications and adherence to their controller prescriptions. Detecting poor adherence can be a challenge in clinical practice as there is no standardized method for its evaluation.31 Each of the commonly used measurement tools have strengths and limitations. The current methods for measuring adherence, both subjective and objective, have several flaws and even the current gold standard, electronic monitoring devices, have limitations.32

When carefully collected, self-reported adherence information can provide critical insight into the nature of patients’ problems with adherence. In addition, because there is no evidence to suggest that adhering patients will misrepresent themselves as non-adherers, self-report measures will identify the honest non-adherers.10

There is emerging evidence that biomarkers of airway inflammation and oxidative stress in exhaled breath condensate (EBC) reflect changes in the airway lining fluid and are altered both in pulmonary and non-pulmonary diseases. Recently, Cafferelli et al.33 showed that children with moderate acute exacerbation of asthma had a significantly lower EBC pH than controls. However, the increase of EBC pH values after treatment did not reach statistical significance in asthmatic children. The authors concluded that additional research in larger populations is warranted to determine whether any modification of EBC pH values may be useful to guide treatment of asthma exacerbations.33

Our study features both physician-administered questionnaires via face‐to‐face interviews with patients, and parents assessing the regular use of long-term asthma-control medication and determining inhaler techniques in asthmatic children.

In conclusion, adherence to long-term asthma-control medications was better with younger patients. The level of asthma control and the pharmaceutical form or number of drugs had no effect on the regular use of medications. The most common cause of irregular drug use was forgetting to take the drug. Moreover, patients were not able to obtain optimal information from a single inhalation-technique training session; repeated training is thus necessary to ensure asthma control and the successful treatment of asthmatic children.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.