Although patient centred communication is associated with patients’ daily medication adherence, the exact communication phenomena promoting high treatment adherence remain elusive.

Patients and methodsWe used conversation analysis of videotaped follow-up consultations of seven outpatients (4–13 years of age) with chronic asthma and their caregivers, consulting two paediatric respiratory physicians in a practice in which high treatment adherence has been documented, to explore the language paediatricians use to promote their patients’ adherence to daily controller medication.

ResultsStarting the consultation with the patient’s (and caregivers’) agenda commonly resulted in presentation of issues new to the physician. Information was mostly provided in response to patient/caregiver questions, prompting the delivery of specific information tailored to the patient’s and caregivers’ needs. Although patients and caregivers showed resistance in response to unsolicited information and advice, they always accepted the doctor’s explicit request for agreement with proposed treatment. The doctor’s description of favourable treatment results in most patients prompted caregivers’ willingness to accept treatment proposals.

ConclusionsPaediatricians with a documented success in achieving adherence to controller medication in their patients with asthma tend to start consultations with the patient’s agenda, provide information in response to questions, offer reassurance on overall treatment effectiveness, and seek explicit agreement with a treatment proposal.

Adherence to daily medication is of key importance in achieving adequate control of chronic diseases, both in adults and in children.1,2 However, adherence to long-term therapy for chronic illnesses in developed countries averages only 50% of the prescribed dosages.3 Because poor adherence has major impact on disease outcomes and patients’ quality of life, improvement of treatment adherence is of critical importance, both from the perspective of individual patients and in terms of health economics.1–3

Medication adherence behaviour is strongly determined by patients’ illness perceptions and medication beliefs.4–6 A major goal of a consultation with a patient with a chronic disease, therefore, is to align these perceptions with the medical evidence on the disease and its treatment.7 Taking such a patient-centred approach in consultations enhances adherence,7–9 but most consultations in daily clinical practice remain doctor-centred, with a predominance of instrumental communication on biomedical issues.10,11 Whilst most physicians express the intent to take a patient-centred approach and apply shared decision making with their patients, they feel inadequately trained to perform it.12,13

Although the principles of effective patient centred consultations have been described,14–16 the exact communication phenomena related to treatment adherence remain elusive. Conversation analysis is a qualitative approach to analyse communication between individuals allowing a rich description of the phenomena encountered, without limiting the analysis to testing predefined hypotheses. Previous research using conversation analysis showed that conversation in medical consultations has a characteristic pattern of action sequences.17–19 For example, the greeting sequence in which a first ‘hi’ puts a normative obligation on the recipient to reciprocate the greeting, or the question-answer sequence in which a question establishes the normative expectation of an answer from the question recipient. In medical consultations, the choice of the opening question by the physician strongly influences the problem presentation by the patient.20 Similarly, the normative order of sequences can prompt a patient to express agreement or understanding verbally even when s/he mentally does not agree or understand. A doctor can hear a patient agree and assume an underlying mental state of ‘agreeing’ but has no access to this mental state.18,21 Thus, the way in which doctors use language in encounters with their patients can influence the patient’s behaviour, both during and after the consultation. Patients can also resist the normative orientations embodied in the doctor’s communicative behaviour. This has been mainly described in responses to doctors’ treatment proposals,22–25 but also in response to a diagnosis and during history taking.26

This study explored physician-patient-caregiver communication in a paediatric practice with documented high long-term adherence to daily controller medication in childhood asthma care.27 We examined the conversation strategies paediatricians apply in these consultations against the theoretical background of patient-centred communication.

Patients and methodsSettingThis study was performed at the Princess Amalia Children’s Centre of Isala, a large (1050 beds) general hospital in a mixed urban-rural area serving a population of 400 000 inhabitants in Zwolle, the Netherlands. Children can only be seen in the centre after referral by a general practitioner. We analysed consultations by the two paediatric respiratory physicians involved in the earlier observational study showing high long-term adherence.27 The healthcare professionals in this practice aim to achieve shared decision making with patients and their parents.11

PatientsWe videotaped scheduled follow-up consultations of seven outpatients with chronic persistent asthma (aged 4–13 years; four boys), who had been prescribed inhaled corticosteroids and who had been under care in our centre for at least three months. Recordings captured audio and video of the patient, caregiver(s), and paediatrician.

AnalysisWe used standard methods of conversation analysis to analyse the seven recorded consultations.28 The video recordings were transcribed, capturing details such as word order, intonation, silences and overlapping utterances to allow the researcher to study the interaction in detail. The videos were transcribed and analysed by two conversation analysis researchers supervised by TK and re-analysed by TK.28

We examined the communication strategies used by the two paediatricians in the study against the theoretical background of patient-centred communication.14–16 We argued that information provision was needed for successful self-management of chronic asthma,16,29 and that acceptance or resistance of treatment recommendations would be of key importance in determining long-term adherence to daily controller therapy.11 Although we thus focused our analysis on information delivery and on resistance or acceptance by patients of the proposed treatment plan, data were not approached with pre-established analytical categories, but were studied to identify phenomena that doctors, patients or parents oriented to as relevant.

Ethical considerationsThis study was approved by the hospital ethics review board (file number 2016-28). All parents gave written informed consent.

ResultsAll consultations were characterised by an opening phase of establishing the agenda for the consultation, a middle phase in which information was exchanged between the child/caregiver and the physician, and an end phase in which decisions were made regarding further diagnosis or treatment and follow-up was discussed. During each of these phases, we observed key strategies of patient-centred care that the paediatricians employed. In the following paragraphs, we will discuss these key strategies one by one, illustrated by representative extracts from the recorded consultations.

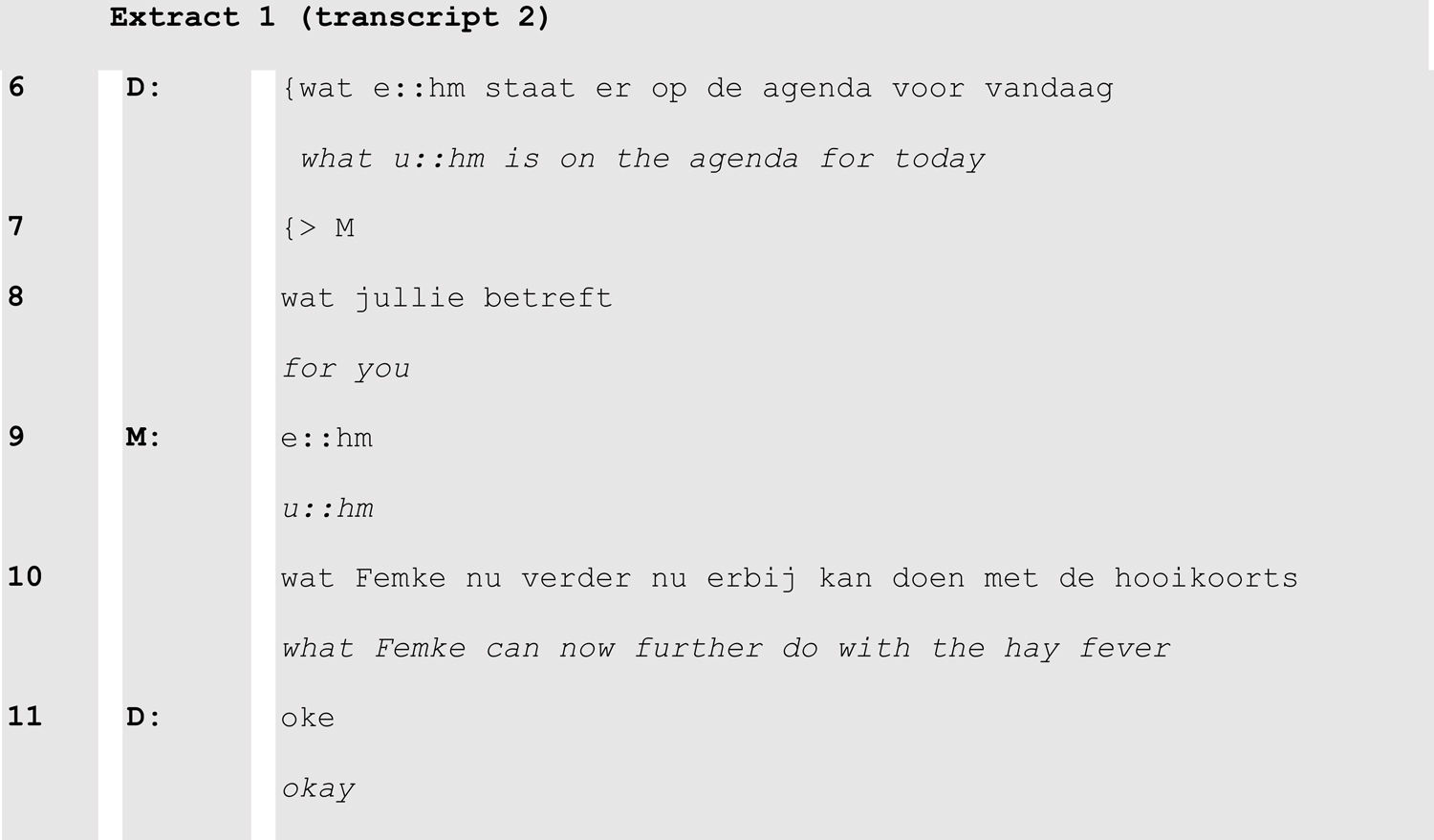

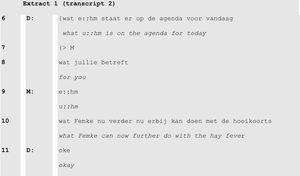

Opening the consultationAfter a friendly welcome and initial chitchat to establish rapport, all consultations started with a question inviting patient and caregivers to present their agenda for the consultation. The design of the doctor’s invitation often produced restrictions on the patient’s problem presentation in terms of addressee (who is addressed to present the problem(s)) and topic (what the problem presentation should be about, and what time period it should cover).

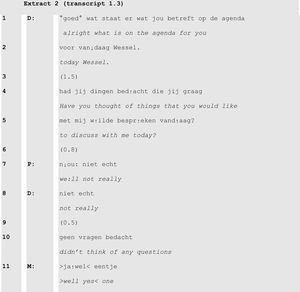

In extract 1 for example, although the physician addressed mother and child with plural ‘jullie’ [you] (line 8) his gaze towards the mother (line 7) during the opening turn of the consultation selected her to respond. Caregivers more often responded to such invitations than the patients themselves, sometimes because the caregiver was invited by the doctor’s invitation (extract 1), or because the patient failed to produce agenda items himself (extract 2).

In this extract, the doctor made a series of attempts to make the patient produce points for discussion before the mother in line 11 self-selected to answer the invitation. The doctor produced two invitations (lines1–2,4–5), a repeat (line 8) and a summarizing formulation (line 10) all of which normatively required responses. In the second version of the invitation, the doctor removed the word ‘agenda’ as a possible cause for Wessel’s failure to answer the first invitation. Also, the doctor remained silent (lines 3, 6 and 9) to allow Wessel to take a turn. When Wessel claimed to have no questions, his mother stepped in.

Agenda questions often resulted in the patient or caregiver presenting an issue new to the physician. For instance, in extract 1 the patient was known to have asthma, but hay fever had not been discussed during earlier consultations.

Information delivery. In all consultations, the doctor played a key role in initiating information delivery to patient and parents, for example to explain a diagnosis or to account for a treatment proposal.

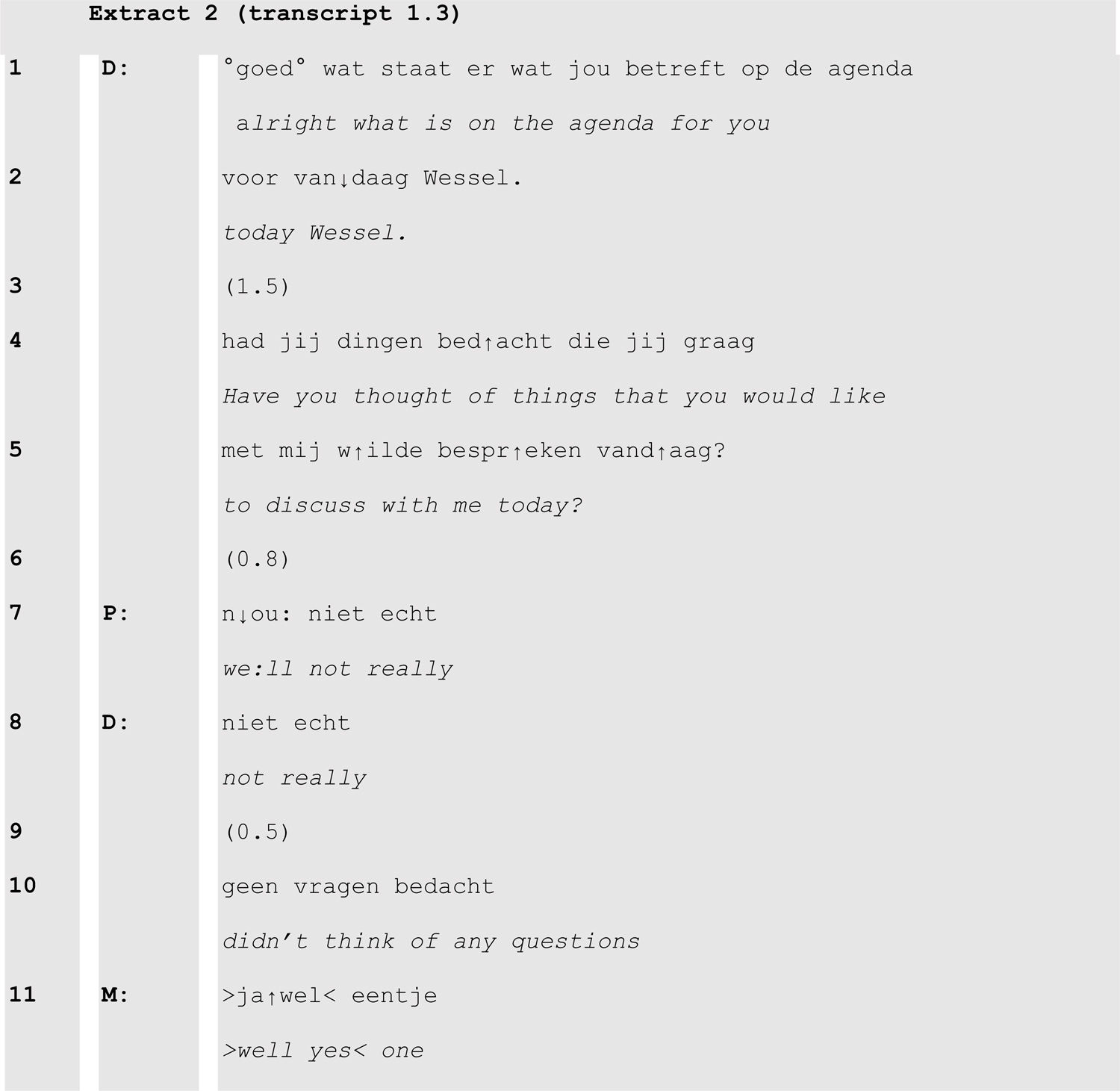

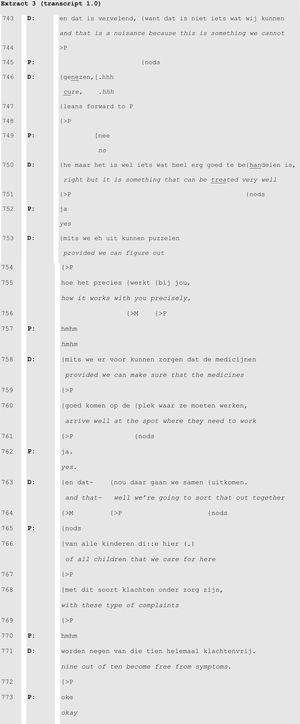

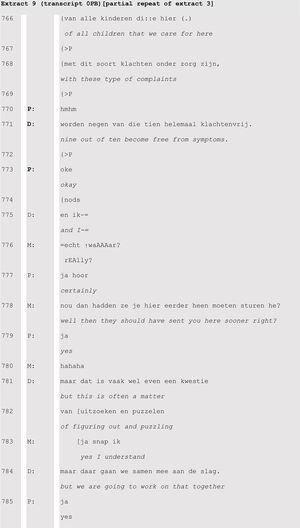

In this extract, the doctor informed the patient and his caregivers that asthma cannot be cured (lines 743-46) but that it can be treated so well (line 750) that it leaves 9 out of 10 patients free from symptoms (lines 766-71). The information was structured into units that are acknowledged by the patient (P) through the production of verbal (‘hmhm’ or ‘yes’) or nonverbal (head nods) tokens of understanding. These tokens were invited by the doctor by gazing at the patient, leaning towards him and by nodding while delivering the information. In lines 743–745 for example, the doctor’s gaze at the patient made the child produce a head nod at the end of the doctor’s statement ‘and that is a shame’. Also, gazing at the patient and leaning towards him simultaneously with the last word of ‘this is something we cannot cure’ (lines 743–746), made the child produce a ‘no’.

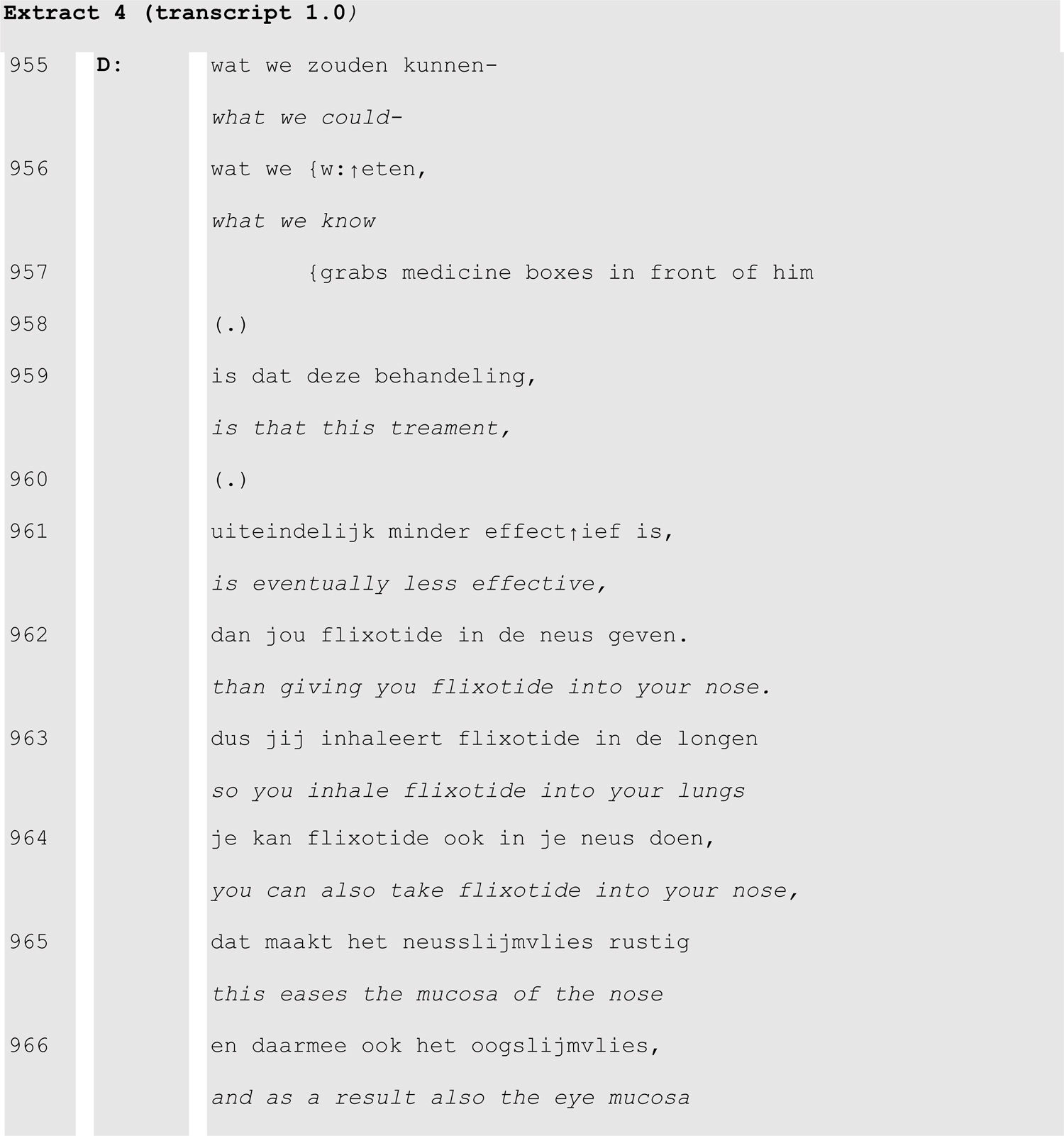

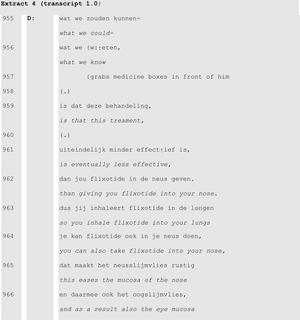

When delivering a treatment proposal, the doctor in extract 4 first provided information as an account for the subsequent proposal to prescribe a nasal spray.

Indeed, as we can see from lines 955–956, the doctor abandoned a proposal initiation (‘what we could [do]’) to start with information delivery instead.

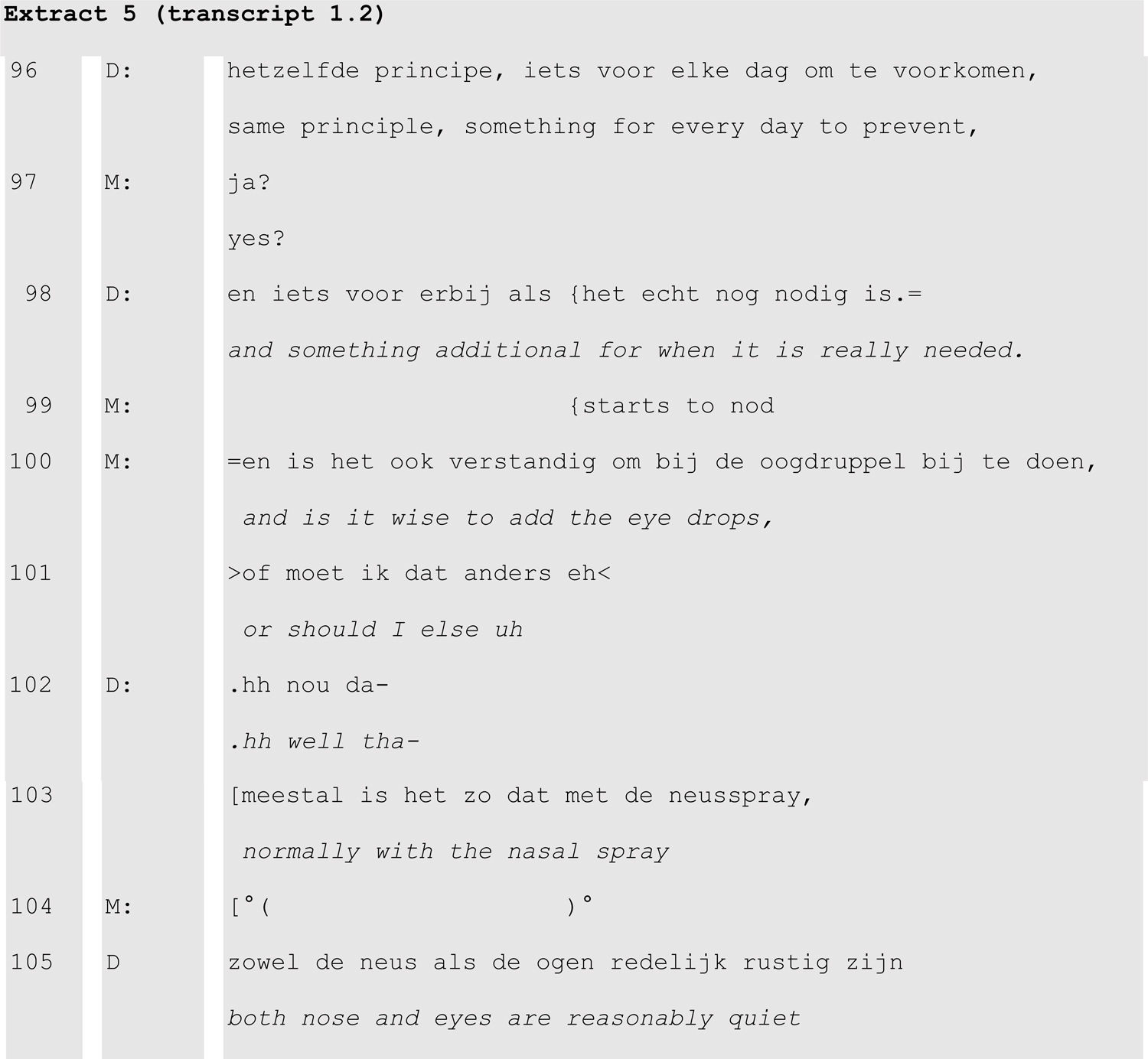

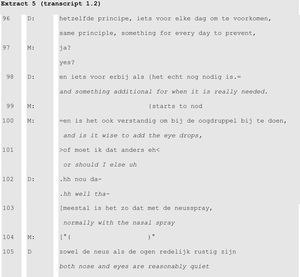

Most information, however, was given in response to patients’ and caregivers’ questions, which were either produced spontaneously by patients or caregivers or invited by the doctor. Spontaneous questions from caregivers typically promptly followed information being given by the doctor (extract 5).

The doctor’s explanation of the use of the different types of medication (preventer and as needed) that ends in lines 96 and 98 prompted the mother’s question about the need for eye drops (lines 100–101). This was followed by the doctor’s information delivery: nasal spray also eases eye symptoms.

Information was often provided in response to patients and caregivers expressing their own agenda for the consultation, but patients and caregivers also seized the opportunity without being explicitly invited. In extract 5, the mother, with her nodding (line 99) even before the doctor has completed his information delivery announced that she was going to take over the turn. Moreover, by latching her question to the doctor’s turn (‘=’ indicates that the two turns were produced without the slightest gap in between) she again showed that she had planned her question already in the course of the doctor’s explanation. Questions such as these prompted the delivery of specific information tailored to the patient’s and caregivers’ needs.

From resistance to acceptanceDuring the course of consultations, patients and caregivers displayed resistance primarily in the history taking phase to doctors’ summaries of the problem presentation by patients and caregivers.

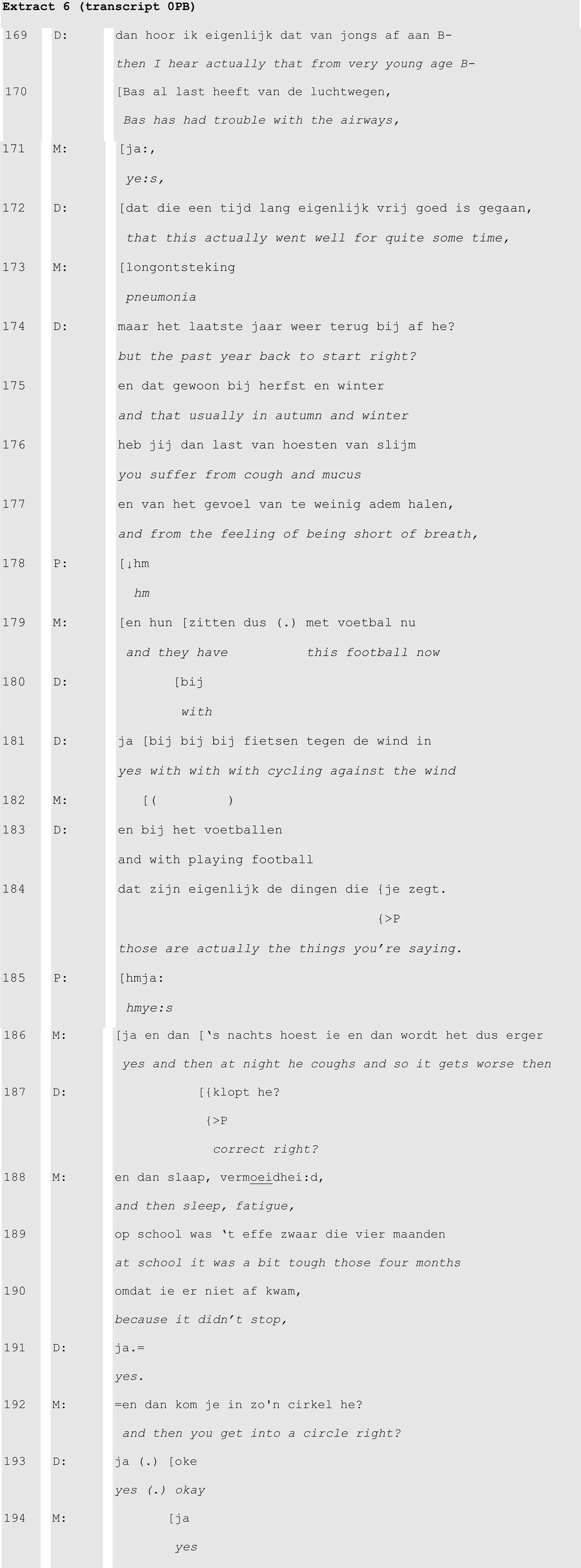

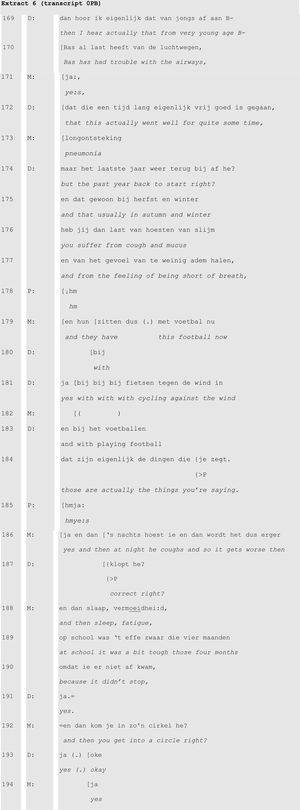

During the doctor’s summary of the preceding problem presentation (extract 6, line 169–187), the patient’s mother resisted the doctor’s version either by upgrading (line 170: doctor ‘trouble with the airways’ > line 173: mother ‘pneumonia’) or adding to the doctor’s rendition (lines 198, 182, 186–190). Even when the doctor switched from talking about the patient (line 172) to talking to the patient (line 176: ‘you’), the patient’s mother responded to the summary. Another type of resistance was found when the patients expressed their inability to improve on an undesirable situation (extract 7).

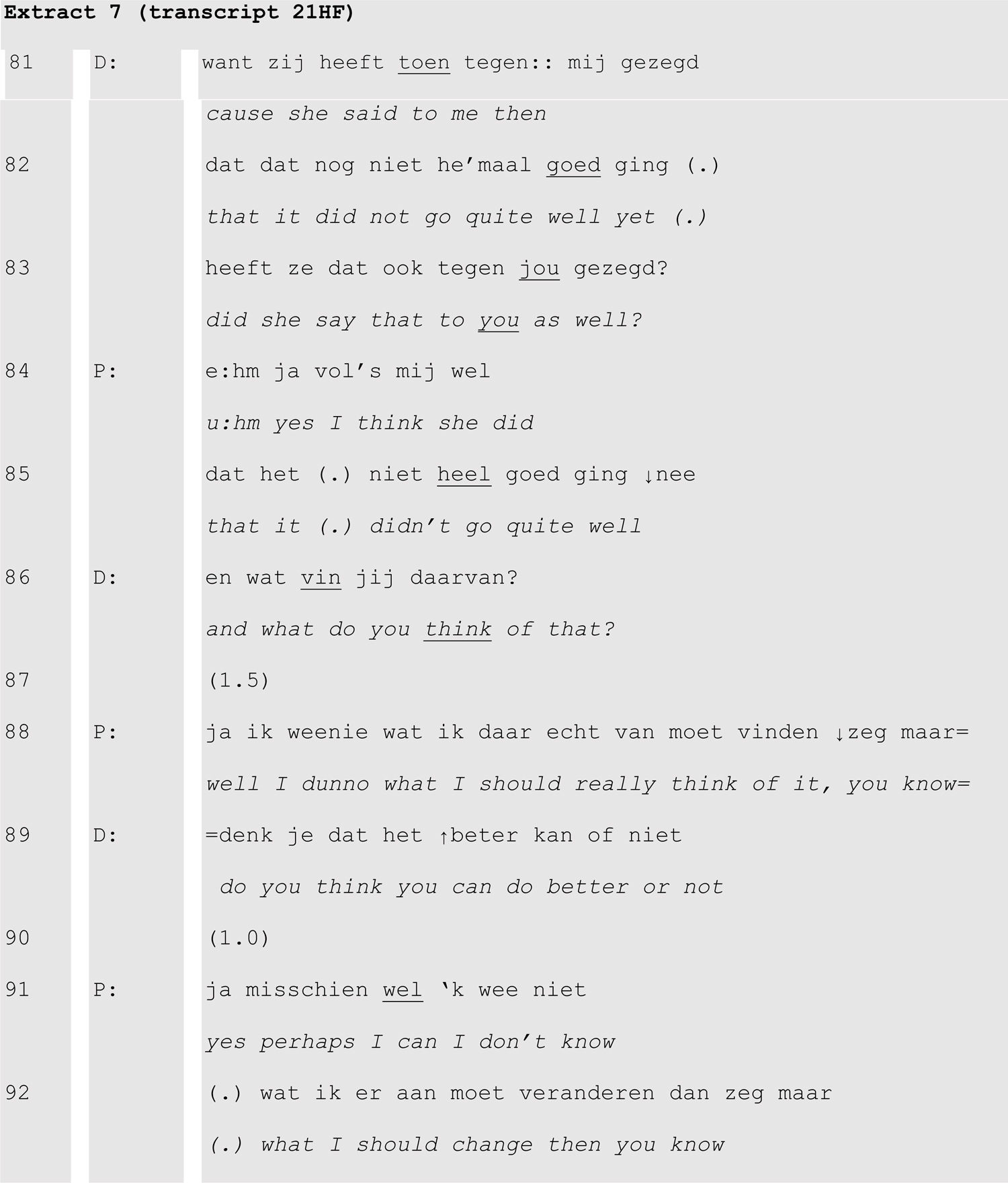

After confronting the patient with the nurse’s opinion that she is not using her medication as prescribed (lines 81–82), the doctor invited the patient to say what she thought of this (line 86). Although this invitation was designed as open to any kind of thought, its position following the reported opinion of the nurse invited the patient to agree or disagree with that opinion. The patient resisted this by claiming that she did not know what to think of it (line 88) or how to improve her medication use (line 92).

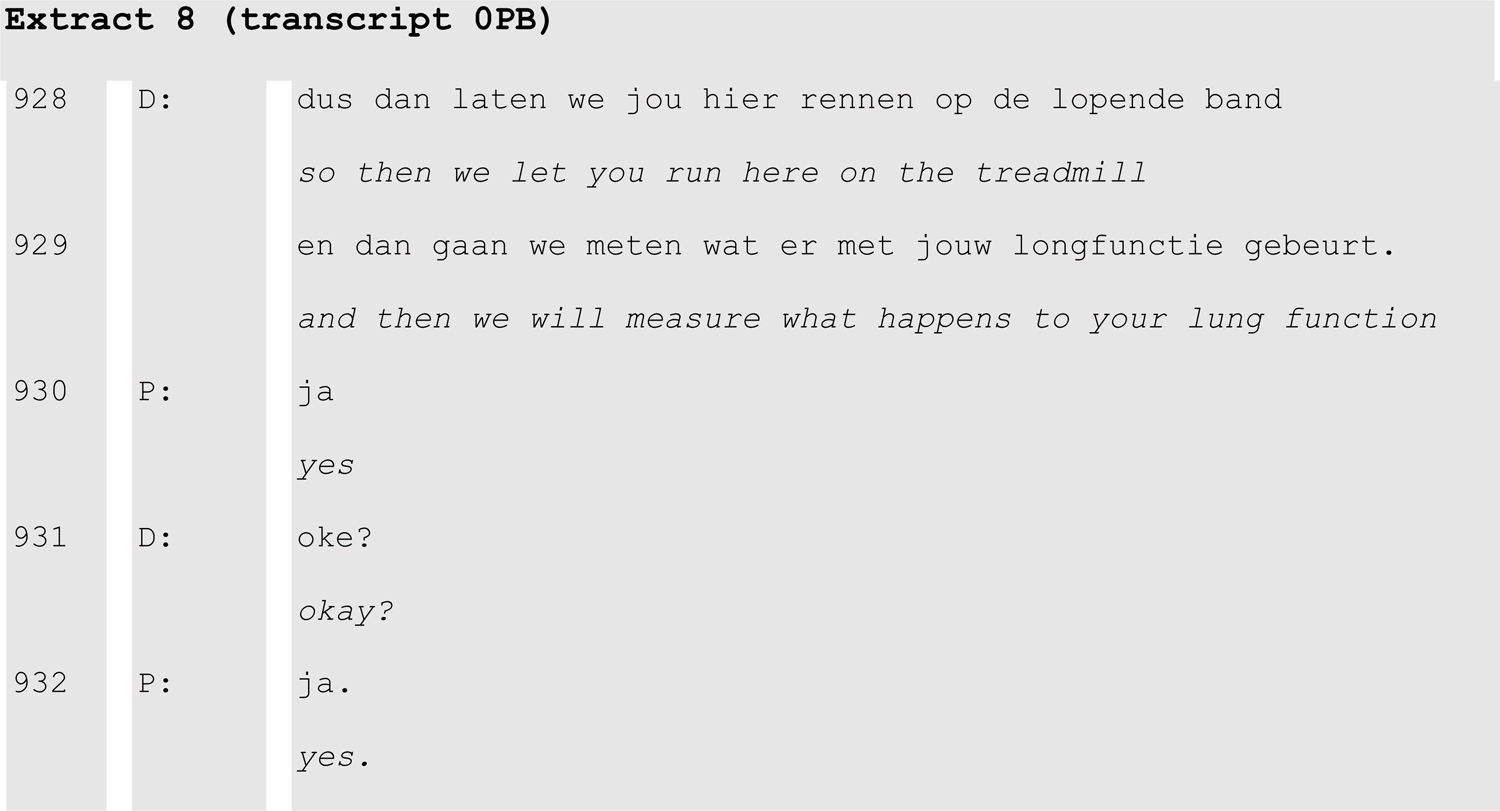

Patients’ and caregivers’ resistance was seen almost exclusively in response to doctors’ formulation of information about the patient. Patients or caregivers never resisted the doctor following a doctor’s request for agreement with proposed treatment. In our data, doctors often responded to patients’ or caregivers’ tokens of agreement with requests to confirm the agreement (extract 8).

In this extract the doctor finalized a proposal in lines 928–929 and the patient responded with agreement in line 930. Following this, the doctor produces an explicit request to confirm this agreement (‘okay?’) and gets another ‘yes’. Such explicit requests were issued by a doctor to initiate the closing of the phase of the diagnostic testing or treatment decision and to proceed to the closing of the consultation.

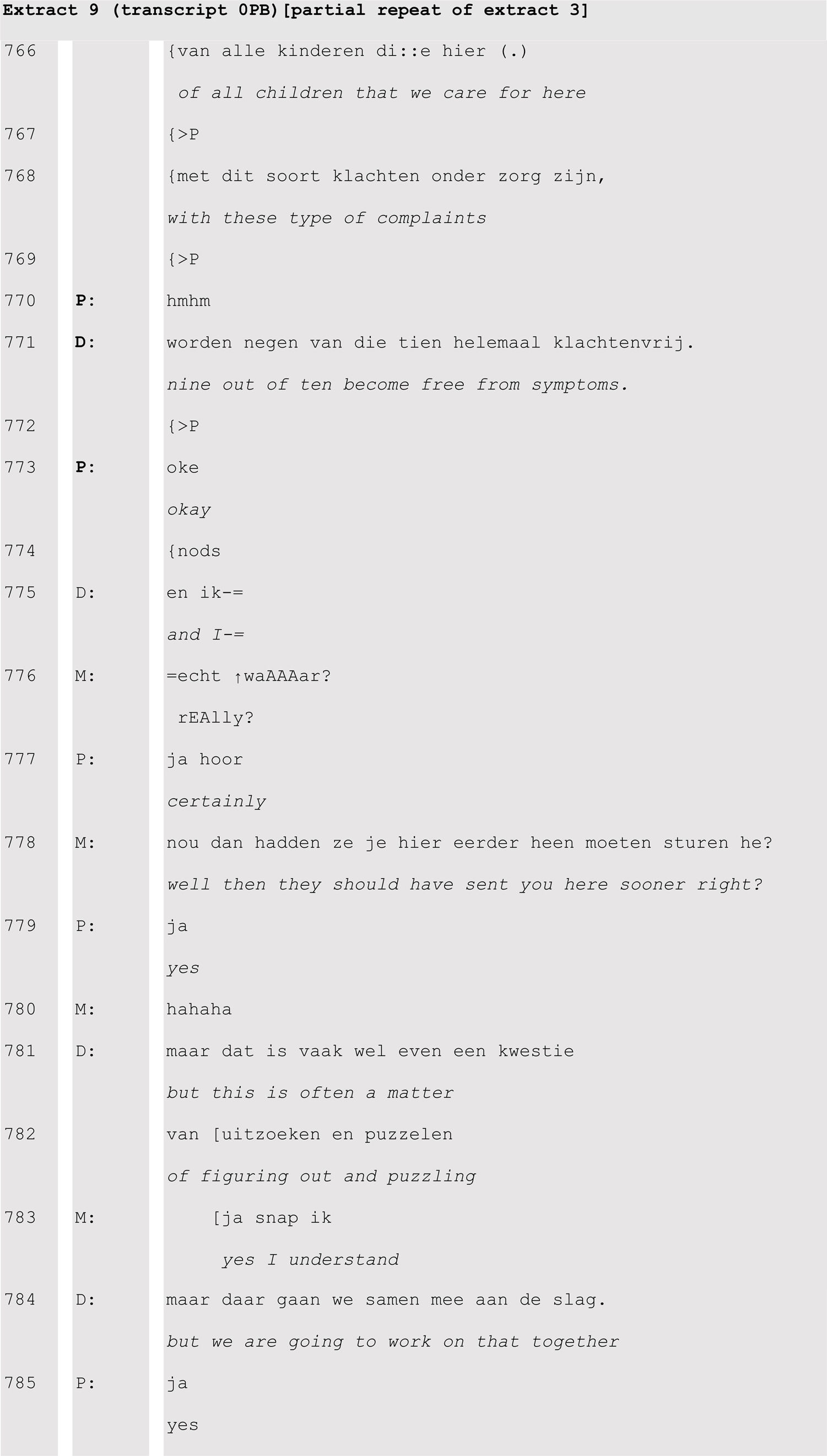

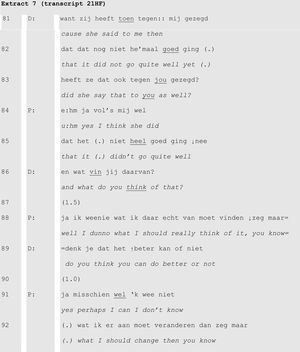

Resistance was most often found in the earlier stages of problem presentation (extract 7) and diagnosis. Transition from resistance to acceptance was typically observed when the doctor provided information on either the treatment results in other patients in the same hospital (extract 9) or on the aims of the treatment (extract 10).

The doctor’s statement that nine out of ten of the hospital’s patients with these complaints become symptom-free was followed by the patient acknowledging this (lines 773-4) and a more enthusiastic response from the mother (“really?”, line 776; to her son “then they should have sent you here earlier” (line 778) and laughter in line 780). After this she immediately accepted (line 783) the doctor’s provision that this will take some “figuring out” (line 782).

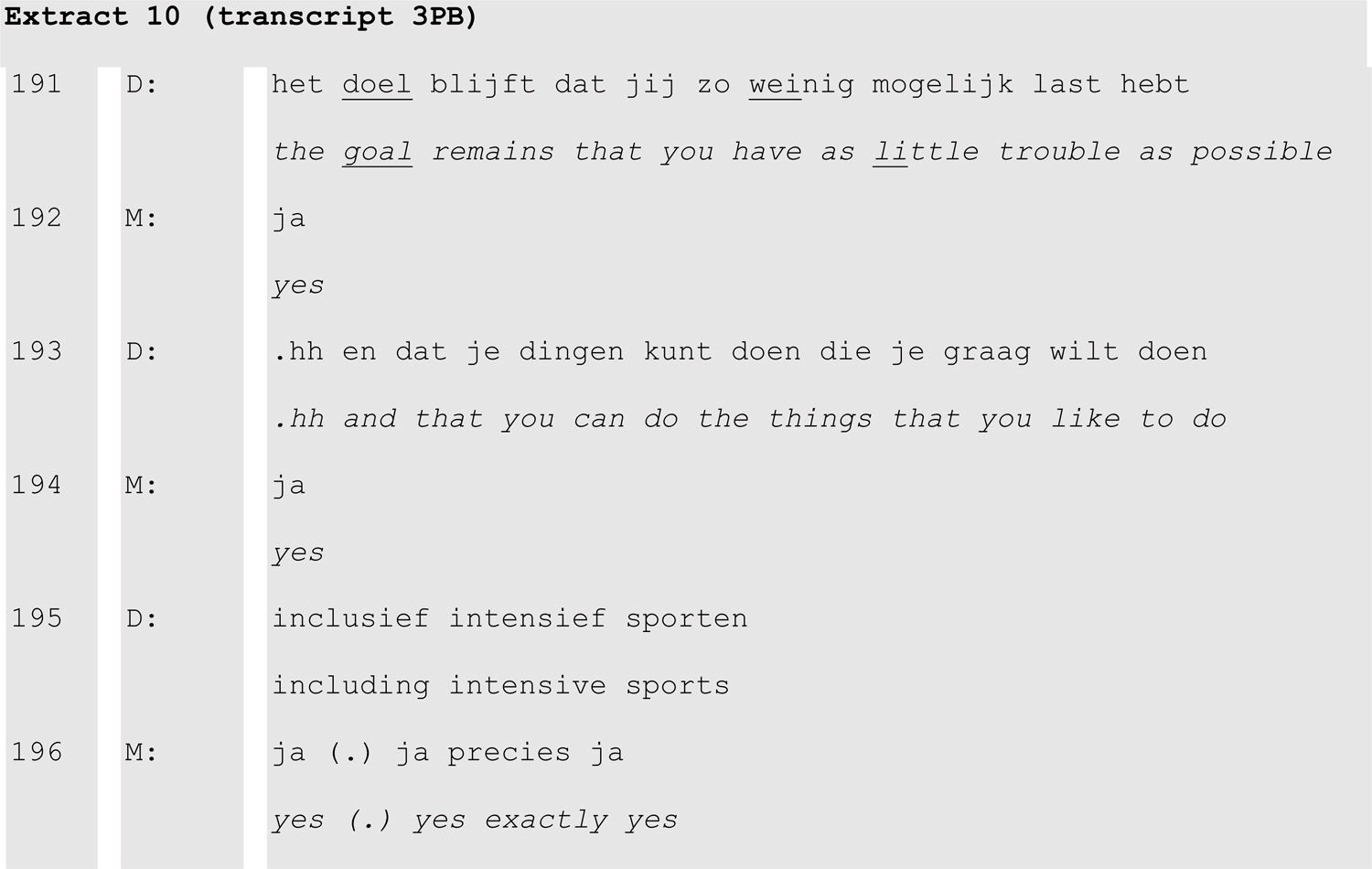

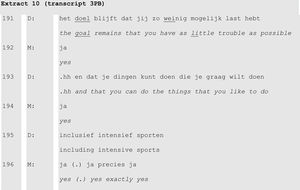

The doctor stating the goal of the treatment (lines 191, 193, 195) and picturing the intended perspective for the patient being able to play sports intensively received a strongly agreeing response from the mother (line 196).

DiscussionThis study explored communication strategies used by physicians in a practice in which high treatment adherence has been documented. Using conversation analysis to study their consultations, a number of potentially useful strategies were identified to promote adherence in their patients: opening the consultation with the patient’s agenda; information delivery linked to either the presented diagnosis or in response to questions by patients or caregivers; presenting favourable results of treatment in the majority of patients seen at the hospital; and moving from resistance to acceptance by explicit third position requests for agreement on the diagnostic or therapeutic plan.

Opening with the patient’s agendaThe design of the opening question of the consultation has a strong impact on both the length and the content of the patient’s problem presentation.20 In our study, all consultations opened with a question addressing the patient’s agenda, which commonly resulted in the presentation of issues that were new to the physician, and could thus not have been on the doctor’s agenda. Time constraints usually drive physicians to limit the number of issues that can be discussed in a consultation,13 particularly in follow-up consultations.7 As a result, most communication in follow-up consultations is instrumental (i.e., serving medical purposes) following the doctor’s agenda.10,30 The consultations in the present study did not exceed the scheduled consultation time (15 min for a follow-up consultation and 30 min for a first consultation), suggesting that the perception of time constraints should not prevent physicians from exploring the patient’s agenda. Exploring the patient’s agenda at the very beginning of the consultation establishes focus and increases the probability that what’s on the patient’s and caregivers’ minds is addressed and not ignored.15 This will help to focus on the patient’s perspective on the symptoms, the diagnosis, and the proposed treatment plan, which is considered of key importance in promoting adherence.8,11

Information deliverySelf-management education is a key component of successful management of chronic diseases in adults and in children.16,29 Although a certain amount of knowledge on the nature of the disease and the rationale of treatment is needed for patients to be able to self-manage their disease,5,31 education interventions alone are insufficient to improve adherence to daily medication in children with chronic disease.32 To promote adherence, the patient’s and caregivers’ beliefs on illness and medication need to be aligned with the medical model of the disease.4,5,11 It is likely that this can be promoted by organizing the consultation in a patient-centred fashion.7–9 It is therefore not only the content, but also the way of delivering the information that determines the effects of self-management education. The present study points out some strategies in information delivery (education) which may promote adherence. A key issue appears to be that information delivery is not a unidirectional process from health care professional to patient, but a dynamic dialogue with information structured into manageable units that patients and caregivers can acknowledge or respond to, either by follow-up questions or by resistance than can then be explored.33 In the present study, the paediatricians chose to provide information on the mechanisms of disease and effective self-management not in one information-rich and lengthy exposé towards the end of the consultation, but as selected bits of information which were deemed relevant, either based on something the patient or caregiver said at that moment, or in response to specific questions from patient or caregivers. This approach of providing information in manageable units in response to patients’ utterances or questions will help doctors to tailor information delivery to the patient’s needs, which is considered important to activate patients to make their own informed choices.34

Presenting favourable results in the majority of patientsIn a number of consultations, the doctor presented favourable results of the proposed treatment plan in the majority of patients with the same diagnosis at the doctor’s hospital. This generated enthusiasm from caregivers in this study (for example in extracts 3 and 9), which is likely to increase their motivation to follow the apparently successful treatment. This is an example of how physicians use empathy and reassurance to improve patients’ satisfaction and self-management.35,36

From resistance to acceptanceA certain degree of resistance to diagnosis and treatment proposals is to be expected. Nobody likes to be diagnosed with a serious or chronic illness, even when it can be effectively managed and controlled. Such resistance, and the emotions associated with it, should be acknowledged and addressed before the patient can be expected to be receptive to information delivery from the health care professional.37,38 In our study, we saw patients’ and caregivers’ resistance particularly in response to doctors’ formulation of information about the patient (for example in extracts 6 and 7). By contrast, no resistance was observed from patients and caregivers when the doctor requested agreement with proposed treatment (as seen for example in extract 9). Like with information delivery, timing appears to be important for explicit requests for agreement with treatment proposals which are most likely to be effective if the patient and caregiver show verbal or nonverbal signs of motivation to self-manage their disease. An appropriately timed request for explicit agreement to follow the proposed treatment plan may thus increase the likelihood of the treatment plan being followed by the patient.8,15

Strengths and limitationsThe strengths of this study include the setting of a clinic in which high treatment adherence has been documented and the use of conversation analysis, a qualitative research strategy aimed at identifying verbal and nonverbal communication strategies which can be used to improve the efficacy of consultations.17,39,40 This study was set up to explore the communication strategies used by the paediatricians who were previously shown to be successful in helping their patients adhere to long-term daily controller therapy.27 We focused on strategies associated with acceptance of treatment proposals after appropriate information delivery to promote adherence.

We acknowledge the following limitations. No adherence data were available on the patients in the present study, but they received the same care from the same physicians as the patients in the adherence study.27 The small sample size (seven consultations) is not problematic in conversation analysis studies, as long as the corpus of data reflects the phenomena being analysed, which was the case in this study. The fact that the consultations were recorded in a single clinic may limit generalizability. Although there is evidence to suggest that the communication strategies discussed here may be effective in promoting adherence, the observational nature of this study and the lack of a control group preclude causal inference.

In conclusion, this study highlights specific communication strategies applied by physicians, which may be related to promoting patient’s and caregivers’ adherence to the proposed treatment plan in paediatric consultations. Establishing the patient’s agenda at the beginning of the consultation and providing information in relation to patient’s and caregivers’ questions improves the patient-centeredness of the consultation. Offering reassurance on the potential for successful management of the condition may be useful if appropriately timed after the patient has been allowed to express resistance and emotion in relation to the diagnosis. An explicit request for a confirmation of agreement on proposed treatment may help to establish a feeling of co-creation of a plan which will likely increase the likelihood of it being followed. Our findings reinforce earlier studies showing that investing both in the beginning (patient’s agenda setting) and the end (seeking explicit agreement on the treatment plan) of a consultation helps in improving the consultation’s efficacy.8,15

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Eric de Groot, Aileen van der Neut and Florentine Roerink for their invaluable help in collecting the data, transcribing and analyzing the consultation videos.