FOREWORD

When the Spanish Society of Clinical Immunology and Paediatric Allergy and the Spanish Society of Paediatric Pulmonology agreed to organise a joint meeting for May 2004, they set up a task force to draw up a document that would review the basic features of children's asthma treatment and would unify criteria that had been apparently diverse before then. The first meeting of this task force was held in June 2003 and laid down the guiding principles for this document. Special attention was paid to those periods of life in which asthma is more difficult to both diagnose and to treat. The prediction of the asthma phenotype, as a factor to consider in certain therapy decisions, was included for the first time in a guide of this kind.

The document was not conceived as an exhaustive guide. Consequently, such basic questions as education and self-care were not dealt with because there is general consensus on them.

The most important aspect of the document is the bringing together of two hitherto disparate visions of children's asthma. Both societies assume full responsibility for the document, in which every sentence has been checked carefully. The basic aim is to offer clear, uniform criteria for asthma treatment in Paediatrics.

Both Societies hope that this is not the end of the joint work, but that it will continue on a regular basis with other initiatives, including the updating of this document in the future.

INTRODUCTION

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of asthma in Spain is known in children over six years of life, but no studies on younger children exist. Unlike in Anglo-Saxon countries, asthma prevalence in Spain is relatively low: about 9 % of 13-14 year olds reported symptoms during the preceding twelve months; and 10 % of parents of 6-7 year-old children report that their children suffered wheezing in the same period. This prevalence was similar in older children in 2002 and in 1994, whereas it increased markedly in 6-7 year olds (from 7 % in 1994 to 10 % in 2002). Severe wheezing is much less common in both age groups (around 2 %). This also increased in the 6-7 year-old group, whereas it remained steady among 13-14 year olds 1. At these ages there appears to be greater prevalence and severity of asthma in the coastal areas than on the central plateau 2,3.

Definition

For the purpose of this document, which refers to children, with particular emphasis on the first years of life, and as the pathophysiology of asthma is largely unknown, the definition of the 3rd International Paediatric Consensus 4,5 is the best one to use: "Recurrent wheezing and/or persistent coughing in a situation in which asthma is likely and other less frequent illnesses have been ruled out". From the age of three years, asthma becomes steadily more definitive; and from the age of 6-7 years, the stricter pathophysiological definitions of general guidelines can be used (GINA 6, NHLBI 7, GEMA 8, etc.).

Asthma phenotypes

Although the pathophysiology of asthma is not well understood, there are different clinical phenotypes that have been characterised in various cohorts in several countries 9-19 the results of which have been extensively published. Though cautiously, we think that these phenotypes can be applied to Spain. This document aims to establish the best line of treatment for each phenotype, based on the scientific evidence available. Therefore, accurate definitions of these phenotypes are crucial:

Transient asthma

1. It starts before the third year of life and tends to disappear between the ages of 6 and 8 years. It accounts for 40 %-50 % of all cases of asthma.

2. It is not atopic (normal total IgE and/or negative skin tests and/or Phadiatop, along with absence of stigmata atopic dermatitis (eczema), for example and of family history of allergy).

3. Lung function is reduced at birth, and becomes normal by 11 years of age.

Early-onset persistent asthma

1. It starts before the third year of life and lasts beyond the age of 6-8 years. It accounts for 28 %-30 % of all asthma cases.

2. Normal lung function at 12 months and had reduced at 6 years.

Two sub-phenotypes of this can be distinguished:

Atopic

1. High total IgE and/or positive skin tests, generally with stigmata and family history of allergy.

2. Bronchial hyper-responsiveness.

3. Usually persists up to the age of 13 years.

4. The first episode usually appears after the age of 12 months.

5. Predominant in boys.

Non-atopic

1. Normal total IgE and negative skin tests, without stigmata or family history of allergy.

2. Bronchial hyper-responsiveness, but which diminishes over the years.

3. Usually disappears at the age of 13 years.

4. The first episode usually appears before the age of 12 months and is related to bronchiolitis due to respiratory syncytial virus infection.

5. Affects both genders equally.

Late-onset asthma

1. It starts between 3 and 6 years of age. It accounts for 20 %-30 % of all cases of asthma.

2. Normal lung function at 6 years of age, which deteriorates subsequently.

3. Often atopic (atopic history in mother, rhinitis in early years and positive skin tests by the age of 6 years).

4. More frequent in boys than in girls.

5. It is an atopic persistent asthma, but with a late onset.

Prediction of asthma phenotype

For practical reasons, it is important to try to establish the phenotype of a particular child in his/her first episode. A child with early wheezing and a major, or two minor risk factors, from the list below, will be highly likely to suffer persistent atopic asthma. However, it must not be forgotten that these criteria provide a low sensitivity (39.3 %, i.e. they include a lot of false negatives), but quite high specificity (82.1 %, i.e. they exclude almost all false positives) 20.

Major risk factors

1. A parent with medically diagnosed asthma.

2. Medical diagnosis of atopic dermatitis.

Minor risk factors

1. Medical diagnosis of rhinitis.

2. Wheezing unrelated to colds.

3. Eosinophilia ≥ 4 %.

The development of specific IgE antibodies to egg during the first year of life is a predictive indicator of atopic illness. It is the main and earliest serological marker of subsequent sensitisation to inhaled allergens and the development of respiratory allergy 21,22. In addition, when allergy to egg is linked to atopic dermatitis, there is 80 % probability of respiratory allergy being present at four years of age 23.

DIAGNOSIS OF ASTHMA IN CHILDREN

Clinical assessment

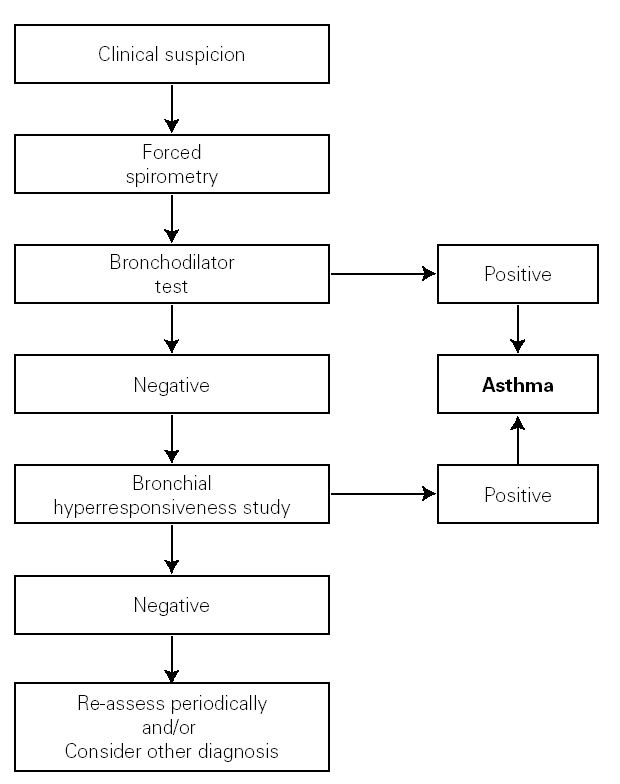

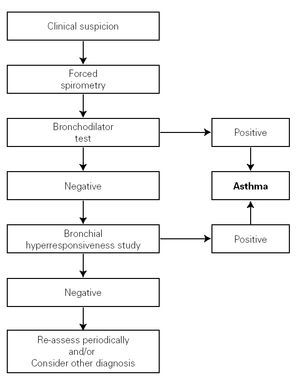

The clinical history must aim to clarify the most important asthma-related points, especially those relating to the differential diagnosis. The symptoms, signs and characteristics of the episodes must be recorded; the symptom-free periods have to be assessed; and any precipitating and aggravating factors need to be identified (see the diagnosis algorithm in figure 1).

Figure 1.--Algorithm for asthma diagnosis (modified from ref. 51).

Functional assessment

The examination of the respiratory function seeks to confirm the diagnosis of asthma, to measure the severity of the disease, to control its evolution and to monitor the response to treatment. In collaborative children, forced spirometry can be used, as its simplicity and cost make it the main test for measuring bronchial obstruction. Other tests can be used for non-collaborative children, such as body plethismography, impulse oscillometry, occlusion resistances or thoraco-abdominal compression.

The reversibility of the bronchial obstruction and/or the degree of bronchial hyper-responsiveness need to be studied. For this purpose, bronchodynamic tests, such as the bronchodilation test and non-specific bronchial hyper-responsiveness challenge tests (metacholine, exercise etc.), are used.

Bronchodilator test

It consists of a basal forced spirometry, repeated 15 minutes after administering a beta2-adrenergic agonist inhaled for a short time (400 μg salbutamol = 4 puffs, or equivalent of terbutalin). This should be a routine examination in every child with suspected asthma, including those with normal FEV1. The use of portable devices to measure peak espiratory flow (PEF) for functional diagnosis of asthma is not recommended.

There are various methods or indexes to express the bronchodilator response, and the most common of them is the percentage change from the initial value in FEV1, i.e. Δ % = [(FEV1 post FEV1 pre)/FEV1 pre] × 100. An increase in FEV1 of 12 % over the basal value or 9 % over the theoretical value 8 (Evidence C) is considered positive. A normal lung function test with a negative bronchodilator test does not rule out a diagnosis of asthma.

Bronchial Hyper-responsiveness

Bronchial challenge tests demonstrate the presence or absence of non-specific and/or specific (due to allergens) bronchial hyper-responsiveness. Normally, these are not needed for the diagnosis and monitoring of asthmatic children, but may be very useful for a differential diagnosis.

Allergy assessment

The aim of this assessment is to determine whether there is/are a relevant allergen or allergens involved in the pathophysiology of the child with asthma. If so, proper measures of prevention can be adopted.

The main techniques in this evaluation are the skin tests: the prick (simple, rapid and safe) or the intradermal test. However, we may find occasionally false positives or negatives, and the skin tests have to be complemented by other diagnostic tests such as the measurement of serum antigen-specific IgE (RAST or CAP system). On occasions, the specific bronchial challenge test may be necessary to detect the allergen involved.

A positive skin test or a high level of specific IgE only indicates allergic sensitisation.

MANAGEMENT OF THE ACUTE EPISODES IN PAEDIATRICS

General considerations

1. The therapy of an acute asthma episode will depend on its severity.

2. As there are few studies on the acute episode in the infant, the use of drugs is based on clinical experience and on the extrapolation from data obtained from older children.

3. It is recommended that all health centres have a pulse oximeter available to improve the assessment of asthma episodes.

4. On treating an acute episode, the following must be borne in mind:

a) The time evolution of the acute attack.

b) The medication administered previously.

c) The maintenance therapy that the patient may be receiving.

d) The existence of associated diseases.

5. Mild and moderate episodes can be treated in the primary care setting.

6. The child must be referred to a hospital emergency department when there is:

a) A severe episode.

b) Suspected complications.

c) A history of very severe episodes.

d) Impossibility of a proper follow-up.

e) Lack of response to treatment.

7. The drug dosage and the administration schedule have to be modified in relation to the severity of the episode and to its response to treatment.

Assessment of severity

Table I shows a system for assessing the severity of the acute asthma episode, modified from the GINA guidelines 6.

Drugs

Short-term beta2 adrenergic agonists: These are the first line of treatment. Their benefits in treating episodes have been sufficiently contrasted 24-33 (Evidence B). Inhalation is the route of choice for their administration, as it gives greater benefit with fewer side-effects.

The metered dose inhaler (MDI) system with a chamber is as effective, if not more so, than nebulisers in the emergency department, and is the treatment of choice for mild or moderate episodes of asthma 31,34,35 (Evidence B).

Ipratropium Bromide: Some studies have shown its usefulness, when associated to short-acting β2 agonists, in moderate or severe episodes 36-38, although the evidence on its use in infants is limited and contradictory 39-41. The dose for nebulisers is 250 μg/4-6 hours in children under 30 kg and 500 μg/4-6 hours in those over 30 kg. It should not replace β2 adrenergic agonists.

Glucocorticoids: They have shown their efficacy when used early 42,43 (Evidence B) and the oral, rather than parenteral, is the route of choice 44,45. There is not enough evidence to justify the use of inhaled glucocorticoids in acute episodes 46-48 (Evidence B). The recommended dose is 1-2 mg/kg/day of prednisone (maximum 60 mg) or equivalent. When it is decided to stop them before the tenth day, there is no need for a gradual withdrawal.

Antibiotics: Since most of these episodes are due to viral infections, administration of antibiotics must be an exception.

Treatment in the primary care setting

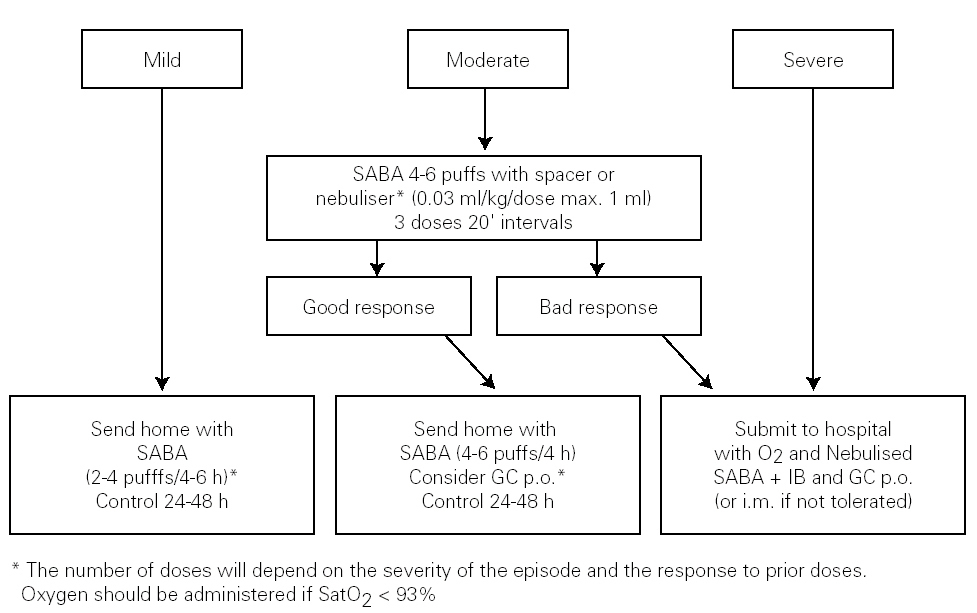

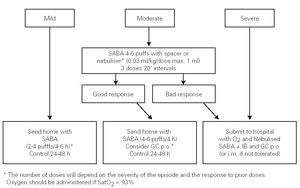

The algorithm of the treatment of the acute episode of asthma in the Primary Care setting is shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.--Treatment of the acute episode of asthma in the primary care setting. (SABA: short-acting b2 adrenergic agonist; IB: Ipratropium bromide; GC: Glucocorticosteroid; oral: oral route; i.m.: intra-muscular route).

Treatment in the emergency department

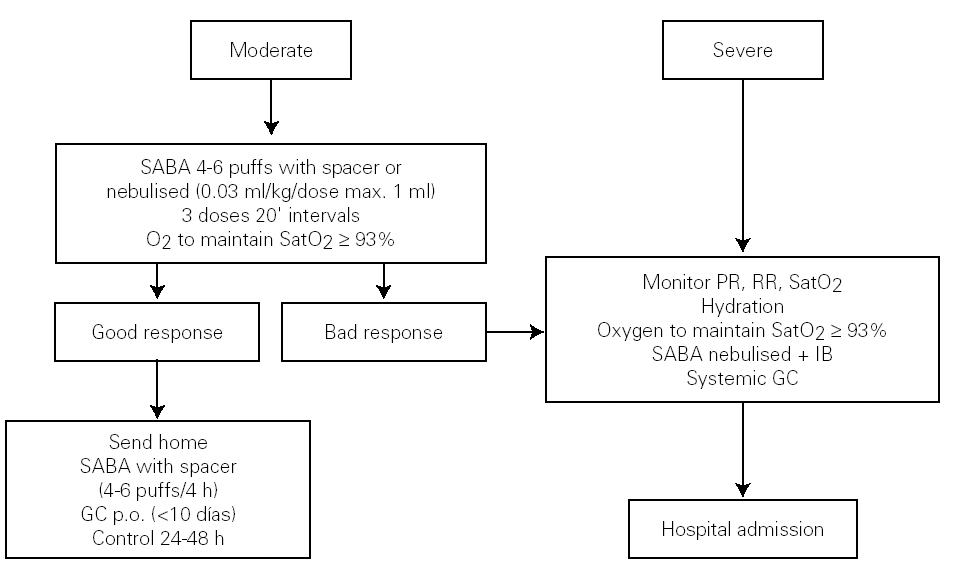

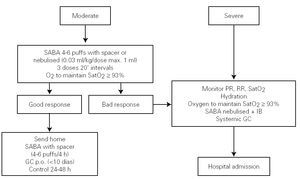

Figure 3 shows the algorithm of the treatment of the acute episode of asthma in the Hospital Emergency Department.

Figure 3.--Treatment of the acute episode of asthma in the emergency department. Long-term treatment must not be suspended, although the dose should be adjusted. (SABA: short-acting b2 adrenergic agonist; IB: Ipratropium bromide; PR: pulse rate; RR: respiratory rate; GC: Glucocorticosteroid; SatO2: Oxygen saturation; p.o.: oral route).

LONG-TERM MANAGEMENT IN PAEDIATRICS

Long-term management has three main aspects:

1. Education of patients and families, along with the control of the environment.

2. Drug treatment.

3. Immunotherapy.

This document does not pretend to be exhaustive. Therefore, for general topics such as avoiding triggers; education; or the pharmacology of asthma drugs, short guides are recommended, such as the protocols promoted by the Spanish Paediatrics Society (AEP) 49,50, or ampler guides such as the SEICAP for the management of the asthmatic child 51, Asthma in Paediatrics 52, The Spanish Guidelines for Asthma Management (GEMA) 8 or the "Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention" of the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 6.

Drug treatment

This section is divided into two, according to the age of the child to be treated: children under three years old and children over three years of age. Most guides focus on adults, with a section devoted to children. No guide specifies a treatment for infants according to the asthma phenotype classification.

Classifying a child's asthma has the sole purpose of helping decide the treatment to choose at first. Subsequently, it will have to be the clinical evolution of the disease and the achievement of the control objectives that drives the modifications of the treatment.

Regardless of the classification of its severity or of the current clinical situation of asthma, the final objective is to control it properly (table II).

Anti-asthma drugs are divided into two basic groups: bronchodilators (usually used to relieve symptoms) and anti-inflammatory drugs (to control the disease) (table III).

The main asthma-controlling drugs are the inhaled corticosteroids. The equipotent doses of these drugs are shown in table IV.

The addition of long-acting β2 agonists to inhaled corticosteroids allows lower doses of the latter to be used. This combination therapy have been extensively tested in adults and in school-age children 53,54.

Inhaled medication must be administered by means of the systems most suited to the age of the patient (see section on inhalation devices).

Children under three years of age

General considerations

1. Many infants who wheeze during their first months of life will cease to have symptoms (transient wheezing), regardless of the long-term treatment employed 55.

2. Most of these episodes are secondary to viral infections 14.

3. The underlying inflammation in these cases is probably different from that found in the atopic asthma of school-children or adolescents 56.

4. As there are few studies on which to base the efficacy of a given treatment in this age-group, physicians will often have to start a treatment and then change or stop it if it is not effective 33,57.

5. Therefore, the recommendations that can be made are largely empirical and assume the following:

a) The infant child has functional β2 receptors 29,58.

b) Both systemic and topical anti-inflammatory drugs have the same anti-inflammatory properties at all ages.

c) Adverse-effects of anti-asthma drugs in infants are similar to those occurring at later ages.

6. It must be borne in mind that in infants a differential diagnosis with other diseases (such as gastro-oesophageal reflux, cystic fibrosis, broncho-pulmonary malformations, immunodeficiency, etc.) is necessary.

Drugs

Inhaled Glucocorticosteroids: In this age group, children with a clinical diagnosis of asthma and risk factors of developing persistent asthma may respond adequately to this treatment 59-65 (Evidence B). However, for infants with post-bronchiolitis wheezing or wheezing episodes only related with viral infections, inhaled corticosteroids are of dubious benefit 66-68 (Evidence B).

Antagonists of leukotriene receptors: Only two studies on children at this age exist. In one of them, treated children had less recurrent episodes in the month after the episode of bronchiolitis 69; in the other, the drug reduced the bronchial inflammation in atopic children 70. There is therefore not a sufficiently sound basis for their current use.

Long-term beta2 adrenergic agonists: In this age group, these are not currently recommended on a routine basis.

Association of long-term beta2 adrenergic agonists and inhaled Glucocorticosteroids: There has only been one study (without a control group) of these drugs in children of this age-group 71. Although its results were positive, more studies on the synergistic effect of glucocorticosteroids and long-term beta2 adrenergic agonists on children under three years of age are needed before the combination of these two drugs can be recommended.

Other anti-asthma drugs such as chromones or theophylline have not proved their efficacy in infants and preschool children 72-78.

Classification

Table V shows the system for classifying asthma in children of this age group.

Treatment

Table VI shows the long-term treatment for children under three years of age.

Children over 3 years of age

General considerations

1. Up to the age of six years, children belonging to the transient asthma group and children with early-onset persistent asthma overlap. Other children will begin to suffer asthma for the first time, constituting the persistent late-onset group 16.

2. The role of atopy from this age has to be assessed by means of a proper allergy test, since it is the main risk factor for persistent asthma 14.

3. From six years of age, as there probably remain few children affected by transient wheezing, most children who suffer persistent wheezing will have early-onset or late-onset asthma 14,16,17,19.

Drugs

Inhaled Glucocorticosteroids: their efficacy at these ages has been well established 47,57,79-89 (Evidence A).

Long-term beta2 adrenergic agonists: In this age group, various clinical trials with both Salmeterol and Formoterol exist. These have found good results, with side-effects that are similar to those of short-acting agonists 90,91.

Antagonists of leukotriene receptors: There is sufficient data on their effectiveness at these ages, although their anti-inflammatory action is lower than that of inhaled corticosteroids. The size of their effect on corticosteroid consumption is still to be determined 92-96 (Evidence A).

Chromones: A systematic review of 24 clinical trials concludes that, in long-term treatment, the effect of sodium chromoglycate is no greater than that of placebo. Thus, this drug is of doubtful utility 97 (Evidence A).

Association of long-term beta2 adrenergic agonists and inhaled glucocorticosteroids: There are studies on the role of long-term beta2 adrenergic agonists in controlling asthma in combination with inhaled glucocorticosteoids in this age-group 53,54,98 (Evidence A). The administration of this combination in the same device could be more effective than when administered separately 99.

Specific immunotherapy can help control the disease if the indications specified in the next section are met.

Classification

Asthma in children over three years of age is classified in the same way as for children under three years of age, as shown in table V.

Treatment

Table VII shows the long-term treatment of children over three years of age.

Specific Immunotherapy

A recent meta-analysis establishes its efficacy, in terms of reduction of symptoms, of relief and maintenance medication, and of bronchial hyper-responsiveness, whether specific or non-specific, but only when biologically standardised extracts were used 100-103 (Evidence A).

Specific immunotherapy is indicated when the following criteria are met 104 (Evidence D):

1. Frequent episodic or moderate persistent asthma, IgE-mediated, when there is sensitisation to a single allergen, a predominant allergen or a group of allergens with cross-reactivity.

2. When the symptoms are not properly controlled by means of allergen avoidance and drug treatment.

3. When the patient has both nasal and lung symptoms.

4.When the patient (or his/her parents or legal guardians) do not want a long-term drug treatment.

5. When the drug treatment causes adverse effects.

Specific immunotherapy is counter-indicated 104 (Evidence D):

1. In children with severe immunological diseases or chronic liver disease.

2. In psychological and social situations which do not allow proper monitoring.

3. As starter therapy in pregnant adolescents, although the corresponding maintenance doses can be administered to girls who began their treatment before pregnancy.

Age is not a limiting factor for the use of immunotherapy, if the previous indication criteria are met (Evidence D).

Although there is no objective data, the minimum length of treatment should be three years and the maximum five 104 (Evidence D).

The subcutaneous route may be replaced by the sublingual one 105,106 (Evidence C). The latter does not have the systemic adverse side-effects that, on very rare occasions, subcutaneous immunotherapy has had 107.

In both subcutaneous and sublingual immunotherapy, only biologically standardised allergen extracts should be used 104 (Evidence B).

Subcutaneous immunotherapy must be administered by trained staff. The patient will remain under observation for 30 minutes after the injection.

INHALATION DEVICES

General considerations

1. The amount of a drug that is administered to a child with asthma depends on the type of drug, the inhalation device, the characteristics of the patient and the interaction between all these factors.

2. Of the several routes for drug administration, inhalation is the route of choice 108,109 (although not all anti-asthma drugs are available in this form, such as the leukotrienes and methylxanthines).

3. The prescription of an inhalation device must occur only after the child and his/her parents have been trained in its use and have demonstrated satisfactory expertise (Evidence B).

4. Re-evaluation of the technique must be a part of the clinical monitoring sessions.

5. In children from 0 to 5 years of age, there is little or no evidence on which to base the recommendations indicated.

6. In general, and a priori, the age is the factor which will orient us towards the use of a particular device, and the border line lies between the ages of 4 and 6 110 (table VIII).

Metered dose inhalers

Common problems with the administration technique mean that over 50 % of the children who receive treatment with a direct application (without a spacer) of a MDI benefit much less than when using other systems 111. Therefore, MDIs directly applied to the mouth must NOT be used in infancy; they must always be used with spacers.

Spacers

The use of a spacer with a MDI solves the problem of coordination, reduces the oropharyngeal deposition and improves the distribution and amount of drug that reaches the bronchii 112 (Evidence A). Its use with inhaled corticosteroids reduces the systemic bioavailability of these drugs and the risk of their systemic effects 113 (Evidence B).

Up to the age of four years, small-volume spacers are recommended: these are the ones with a face mask attached. As nasal breathing in these cases greatly reduces the lung deposition 114, from four years on, if possible and if the child is sufficiently cooperative, the patient should move on to a large-volume spacer without a mask 115,116.

Dry-powder inhalers

Dry-powder inhalers do not contain propellants and the doses are homogeneous, the inhalation technique is easier than with the MDI and they are small and user-friendly, making it easy for the child to carry it. Lung deposition is higher than that achieved with MDIs, but the results are similar when the latter is used with a spacer.

The amount of drug trapped in the oropharynx is higher than that occurring with pressurised inhalers with spacers, but lower than that produced with MDIs without spacers 117,118. The risk of adverse effects increases with the oropharyngeal deposit. The most common inhalers used are those with a multi-dose system (Accuhaler and Turbuhaler). With both systems an inspiratory flow of 30 L/min is enough. These devices are recommended from 5-6 years up.

Nebulisers

At present, the use of nebulisers at home in long-term treatment is restricted to special cases 119. The oxygen-driven "jet" kind of nebulisers are used by emergency departments.

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HOSPITAL-BASED AND PRIMARY CARE PAEDIATRICIANS

1. The care of the asthmatic children must be coordinated between the hospital-based and the primary care paediatricians.

2. Each health area will need to specify this coordination, depending on its own resources.

3. The organisation of care-plans for asthmatic children must include both the hospital care as well as the primary health centre care.

4. The main principles of this coordination are as follows:

a) Hospital care will be greater, when asthma is more severe.

b) The primary care paediatrician will refer the child to the hospital Allergy or Pulmonology Unit when:

An allergy and/or lung function assessment is needed.

He/she cannot control an asthmatic case properly.

There are personal and/or family circumstances of the child that make referral advisable.

c) The hospital based paediatrician (allergologist or pulmonologist):

Will perform a lung function test and/or an allergy evaluation, which will be reported to the primary care paediatrician.

Will recommend treatment guidelines that the primary care paediatrician will try to follow, whilst not losing sight of the fact that the aim is to control the disease.

5. Forced spirometry with the bronchodilation test may be a useful technique for primary care paediatrics both for diagnosing and monitoring the asthmatic child.

6. The Phadiatop and/or the prick tests maybe useful for allergy screening in the primary care setting.

7. However, to perform lung function and prick tests, adequate equipment and proper training (acquired in the paediatric pulmonology or allergy units) are needed.

This article has been simultaneously published in spanish: An Pediatr (Barc). 2006;64(4):365-78.