Urticaria is a common cause for consultation in general and specialised medical practices. There is scarce information on the characteristics of patients suffering acute urticaria in Latin America.

ObjectivesTo investigate demographic and clinical features of patients with acute urticaria attending two allergy clinics in Caracas, Venezuela.

MethodsA prospective study of all new patients who consulted during a three-year period because of acute urticaria. Information on age, gender, symptom duration, previous medical history, body distribution of wheals and angio-oedema, laboratory investigations, skin prick tests, and pharmacological treatment, was collected. Patients were classified according to their age as children/adolescents and adults.

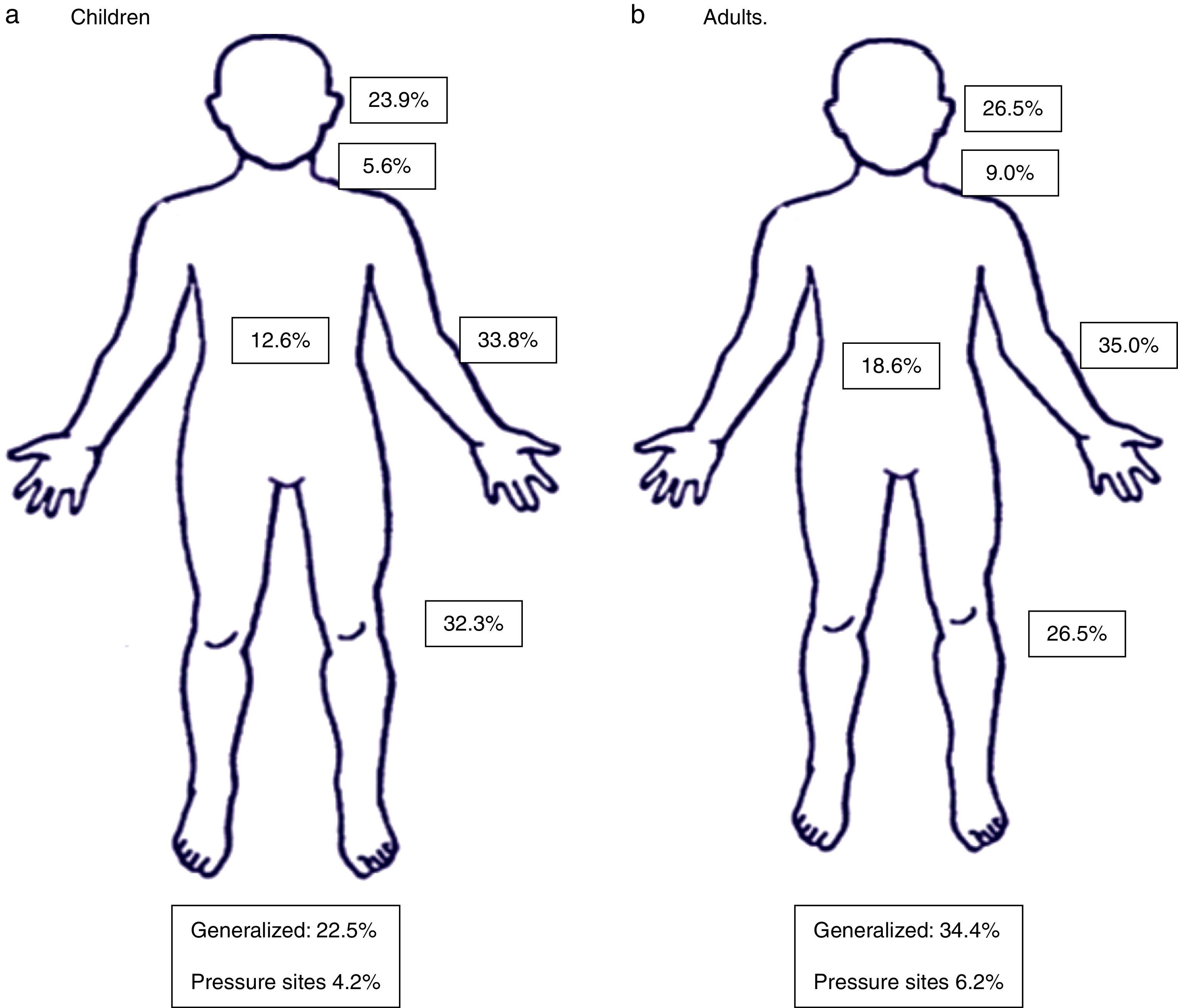

ResultsTwo hundred and forty eight patients (177 adults and 71 children) were studied. Acute urticaria was more frequent in middle-aged atopic female patients. Lesions more often involved upper and lower limbs and head, and 31% of patients exhibited generalised urticaria. Laboratory investigations, performed only in selected cases, did not contribute to the final diagnosis. Most frequent subtypes of acute urticaria were spontaneous, dermographic, papular, and drug-induced urticaria. Most patients were treated with non-sedating antihistamines, with increased use of cetirizine and levocetirizine in children, while 5.6% of children and 20.3% of adults required the addition of short courses of systemic corticosteroids.

ConclusionsAcute urticaria is a frequent cause of consultation for allergists, affecting more often middle-aged female atopic patients. The use of extensive complementary tests does not seem to be cost-effective for this clinical condition. Spontaneous, dermographic, papular and drug-induced urticaria are the most common subtypes.

Acute urticaria (AU) is a common cause for consultation in emergency services, general practices, and specialised dermatology and allergy clinics. The prevalence of urticaria in the general population has been estimated to be between 2.1% and 6.7%1 with lifetime prevalence rates of up to 8.8%.2 It may affect between 15% and 23% of individuals at some point of life,3 and about 40% of patients with urticaria exhibit concomitant angio-oedema (AE).4 Acute spontaneous urticaria is common in infants and young children, particularly in atopic subjects. In fact, in the ETAC study 16.2% of placebo-treated children developed urticaria.5 Furthermore, in a study carried out in Spain, the prevalence of urticaria in the past 12 months was 0.8%, more often in female patients among 35 and 60 years (mean age 40 years).6

The prognosis of acute urticaria is generally favourable with most patients responding to conventional therapies and showing a short-lasting disease, although 20–30% of cases of AU may progress to chronic urticaria.7–11 AU compromises patient's quality of life and pruritus is a major cause of discomfort.12–14

Since there are scarce data on the clinical expression of acute urticaria in Latin America, we have performed a prospective study that investigated the demographic and clinical characteristics of all patients with AU attending outpatient allergy clinics in Caracas, Venezuela for the first time, during a three-year period. This information is relevant for clinicians taking care of patients with this common condition in countries from Latin America and other developing areas of the world.

MethodsThis is a prospective study that included all new patients who attended to two ambulatory allergy services in Caracas, from January 1st, 2010, to December 31st, 2012. After signing the informed consent statement, patients of any age or sex were included into the study. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Clínica El Avila. The following information was obtained by direct patient interrogation and physical examination: age, gender, duration of symptoms, previous or current medical conditions, and body distribution of the wheals and angio-oedema. Patients were classified into two groups according to their age: children and adolescents (1–18 years old), and adults (≥19 years old).

Acute urticaria was defined according to the current International Guidelines on Urticaria and Angio-oedema as the occurrence of wheals and/or angio-oedema lasting six weeks or less.15 Additional laboratory investigations and immediate-type hypersensitivity skin tests with inhalant and food allergens were performed only in selected patients as deemed necessary by the treating allergist according to the medical history and physical examination, as recommended in the guidelines.15 Treatment of AU consisted mainly of second generation (non-sedating) antihistamines and in severe cases with the addition of oral corticosteroids.16

Statistical analysis. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare two groups for non-normal distribution data. Proportions were analysed using the Chi-square test. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsDemographicsDuring the period of this investigation 618 new patients with urticaria and angio-oedema were studied. This amount constituted 21.8% of all patients consulting to the allergy services. Two hundred and forty eight (40.1%) had acute urticaria and 370 (59.8%) had chronic urticaria. Age and sex distribution of patients with AU, as well as the time of disease duration before consulting are shown in Table 1. AU was more frequent in adults, and predominated in female subjects (p<0.05). The number of days with wheals before consulting was not significantly different between children/adolescents and adults.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of studied population.

| Children (n=71) | Adults (n=177) | All patients (n=248) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | P value | n | % | P value | n | % | P value | |

| Female | 34 | 47.8 | – | 129 | 72.8 | – | 163 | 66.7 | – |

| Male | 37 | 52.1 | n.s. | 48 | 27.1 | <0.05 | 85 | 34.2 | <0.05 |

| Duration of wheals (days) | 18.6±10.6 (range 1–40 days) | 17.6±10.1 (range 1–40 days) | n.s. | 18.0±10.4 (range 1–40 days) | |||||

| Mean age (years) | 6.14±5.1 (range 7 months–18 years) | 40.6±15.3 (range 19–83 years) | 30.4±20.9 (range 7 months–83 years) | ||||||

n.s.: not significant.

Table 2 presents a summary of previous and concomitant medical history of studied patients. Rhinitis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis were frequent in children with AU; whereas rhinitis, hypertension and asthma were frequently present in adults, but no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of these comorbidities were present. The body distribution of the wheals and AE is depicted in Fig. 1. Upper and lower limbs, and the head were the most common sites of lesional areas, and 31% of all patients showed generalised urticaria (children 22.5%, adults 34.4%).

Medical history in patients with acute urticaria.

| Disease | Children | Disease | Adults | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Rhinitis | 7 | 9.8 | Rhinitis | 42 | 23.7 | n.s. |

| Asthma | 4 | 5.8 | Asthma | 14 | 7.3 | n.s. |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis | 2 | 2.8 | Chronic rhinosinusitis | 5 | 2.8 | n.s. |

| Atopic dermatitis | 3 | 4.2 | Hypertension | 21 | 11.8 | – |

| Acute rhinosinusitis | 1 | 1.4 | Hypothyroidism | 5 | 2.8 | – |

| Diabetes | 4 | 2.2 | – | |||

| Nephrolitiasis | 2 | 1.1 | – | |||

| Conjunctivitis | 2 | 1.1 | – | |||

| Hyperlipaemia | 2 | 1.1 | – | |||

| Depression | 1 | 0.5 | – | |||

| Seborrheic dermatitis | 1 | 0.5 | – | |||

| Vitiligo | 1 | 0.5 | – | |||

| Nasal polyposis | 1 | 0.5 | – | |||

| Contact dermatitis | 1 | 0.5 | – | |||

| Autoimmune thyroiditis | 1 | 0.5 | – | |||

| Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura | 1 | 0.5 | – | |||

| Breast cancer | 1 | 0.5 | – | |||

| Bladder cancer | 1 | 0.5 | – | |||

| Meniere syndrome | 1 | 0.5 | – | |||

n.s.: not significant.

One hundred and nineteen patients were submitted to prick tests with inhalant and food allergens (Table 3). These tests were positive in 59% of children and 60.8% of adults (p n.s.), more often to domestic mites (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and Blomia tropicalis), American cockroach (Periplaneta americana), dog and cat. Sensitisation to D. pteronyssinus and B. tropicalis was more prevalent in adults than children (p=0.006 and 0.009, respectively).

Results of immediate-type skin tests.

| Children (n=22) | Adults (n=97) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Positive | 13 | 59.0 | 59 | 60.8 | – |

| Negative | 9 | 40.0 | 38 | 39.1 | n.s. |

| D. pteronyssinus | 10 | 45.4 | 57 | 58.7 | 0.006 |

| B. tropicalis | 6 | 27.2 | 46 | 47.4 | 0.009 |

| Cockroach | 4 | 18.1 | 27 | 27.8 | n.s. |

| Dog | 4 | 18.1 | 19 | 19.5 | n.s. |

| Cat | 3 | 13.6 | 16 | 16.4 | n.s. |

| Shellfish | 2 | 9.0 | 8 | 8.2 | n.s. |

| Wheat | 2 | 9.0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Milk | 1 | 4.5 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Cocoa | 1 | 4.5 | 2 | 2.0 | n.s. |

| Mosquito | 1 | 4.5 | 1 | 1.0 | n.s. |

| Feathers | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6.1 | – |

| Moulds | 0 | 0 | 8 | 8.2 | – |

| Peanuts | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.0 | – |

| Soy | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.0 | – |

| Bermuda grass | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.0 | – |

| Chenopodium | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.0 | – |

| Beef | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.0 | – |

| Potato | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.0 | – |

| Fish mix | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.0 | – |

| Tomato | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.0 | – |

| Salmon | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.0 | – |

| Chicken | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.0 | – |

n.s.: not significant.

Only 79 patients (20 children and 59 adults) required laboratory tests. Abnormal results were present in 85% of children and 37.2% of adults (p=0.0001) (Table 4). Increased total serum IgE, leucocytosis, and eosinophilia were observed in 60%, 20%, and 15% of children, respectively, and these abnormal results were significantly more prevalent than in adults (p=0.0001).

Abnormal laboratory results.

| Children (n=20) | Adults (n=59) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | n | % | ||

| Normal | 3 | 15.0 | 37 | 62.7 | n.s. |

| Abnormal | 17 | 85.0 | 22 | 37.2 | 0.001 |

| Increased serum IgE | 12 | 60.0 | 4 | 6.7 | 0.0001 |

| Increased aminotransferases | 0 | 0 | 4 | 6.7 | – |

| Increased erythrosedimentation rate | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5.0 | – |

| Leucocytosis | 4 | 20.0 | 3 | 5.0 | 0.0001 |

| Eosinophilia | 3 | 15.0 | 3 | 5.0 | 0.0001 |

| B. hominis in stools | 0 | 0 | 4 | 6.7 | – |

| Increased gamma glutamyl transferase | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3.3 | – |

| Increased anti-streptolysin “O” titre | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.6 | – |

| Increased total bilirubin | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.6 | – |

| Hyperuricaemia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.6 | – |

| Positive rheumatoid factor | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.6 | – |

| Increased C reactive protein | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.6 | – |

n.s.: not significant.

Table 5 summarises the diagnostic categories for the two age groups of patients. Spontaneous acute urticaria was present in 45.0% of children and 59.8% of adults (p=0.0001). Papular urticaria occurred more frequently in children (39.4% vs 9.9% in adults) (p=0.0001), whereas drug-induced and dermographic urticaia were observed more often in adults (15.2 vs 7.0% and 12.4 vs 5.6%, p=0.0001)).

Acute urticaria subtypes in the studied population.

| Children (n=71) | Adults (n=177) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Spontaneous urticaria | 32 | 45.0 | 106 | 59.8 | 0.0001 |

| Papular urticaria | 28 | 39.4 | 17 | 9.9 | 0.0001 |

| Drug-induced urticaria* | 5 | 7.0 | 27 | 15.2 | 0.0001 |

| Dermographic urticaria | 4 | 5.6 | 22 | 12.4 | 0.0001 |

| Food-induced urticaria§ | 2 | 2.8 | 6 | 3.3 | n.s. |

| Contact urticaria | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.1 | – |

| Cold urticaria | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | – |

| Solar urticaria | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | – |

| Infectious (acute rhinosinusitis) | 1 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.5 | n.s. |

n.s.: not significant.

Cetirizine and levocetirizine were indicated more often in children and fexofenadine, cetirizine, levocetirizine, and systemic corticosteroids were administered more frequently in adults. First generation antihistamines were indicated in only eight patients (3.2% (data not shown)).

DiscussionThis is a prospective study that aimed to investigate the demographic and clinical features of patients with acute urticaria/angio-oedema attending allergy outpatient clinics during a three-year period. AU was more frequent in adult middle-aged female patients, which is in agreement with other studies.9,12 It is likely that patients decided to attend a specialist clinic after failure of the treatment with self-medicated over the counter antihistamines, or after being treated by general practitioners, since the mean time for consultation was delayed for 18.6 days in children and 17.6 days in adults (Table 1).

In patients with AU the diagnostic approach is generally limited to a detailed history and physical examination. Costly complementary investigations are not encouraged due to the self-limited nature of the disease, and are indicated only when clinical data from patient questioning and examination are suggestive of some aetiological factor such as upper respiratory tract viral infections, a common cause in children, foods and drugs (more often antibiotics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]).17

Although in many patients with AU IgE-mediated urticaria/AE cannot be demonstrated, it was interesting to notice that an increased prevalence of concomitant allergic diseases, including rhinitis, asthma and atopic eczema, was present in these patients. In the subset of patients who were skin-tested there was a high prevalence of positive results, about 60%, for the two age groups, which might be indicating that atopy is a predisposing factor for the development of AU.

In general, the results of laboratory investigations did not contribute to the definitive diagnosis in the majority of patients, confirming the recommendations of current guidelines on not to perform extensive laboratory determinations in patients with AU.15

Drugs, foods, viral and parasitic infections, insect venoms, and contact allergens have been incriminated as the most common causes of AU. Spontaneous urticaria was the most common diagnosis for both patient groups, children and adults, followed by papular, drug-induced and dermographic urticaria, and the frequency of these subtypes was not different from findings from other authors.18

Since the present study was carried out in a tropical country, papular urticaria constituted a frequent cause for consultation, especially in children. This clinical picture is defined as chronic or recurrent eruptions characterised as pruriginous papules, vesicles and wheals produced by a hypersensitivity reaction to insect stings.19Culex, Aedes, and Simulidae species of mosquitoes are the most common insects involved, but in some Latin American cities such as Bogota, Colombia, flea bites are major inducers of papular urticaria.20 This subtype is rarely present in studies done in locations with temperate climates, such as North American and European countries, but it is an important clinical picture in tropical and subtropical regions of the world.

Infectious agents have often been incriminated in the induction of AU.21,22 However, in this investigation infections were not a major cause of AU, although we did not routinely perform special tests such as serology for viral agents. Drug hypersensitivity, particularly elicited by antibiotics and NSAIDs, is an important cause of acute urticaria/AE.23,24 However, it is important to take into consideration that some patients, and especially the children, may show U/AE when receiving drugs for the treatment of an acute infectious process, and could tolerate with impunity the same drug later on when they are not infected.25,26 As observed in other studies,27 food allergy was a very rare cause of AU in our patients.

Acute urticaria generally follows a self-limited course, and treatment is centred on avoidance or treatment of the inducing stimulus (for example, drug, food, physical stimuli, infectious agents), and pharmacological therapy for the relief of the symptoms. Second-generation antihistamines constitute the preferred medications for both, children and adults.16,28 Although this study did not intend to assess patient's response to the treatment, it was interesting to notice that cetirizine and levocetirizine were the anti-H1 antihistamines of choice in children, which might be related to the demonstrated safety profile of these drugs in young patients,29,30 whereas in adults a wider group of antihistamines and a higher frequency of utilisation of systemic corticosteroids was indicated. As recommended in the guidelines, sedating antihistamines were rarely used in our AU patients.16

In conclusion, acute urticaria is a common motive for consultation in allergy clinics, affecting more often middle-aged female patients, with an increased prevalence in atopic individuals. Our results do not justify the utilisation of extensive laboratory investigations in patients with AU, which should only be indicated in selected patients according to the medical history and physical examination. Spontaneous, papular, drug-induced and dermographic U/AE were the most common subtypes of AU in this population. The detailed knowledge of the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with AU is helpful for clinicians taking care of patients suffering this common condition.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Patients’ data protectionConfidentiality of data. The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

FundingInvestigator's funds.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.