The diagnostic values for the skin prick test (SPT) diameters and egg white-specific IgE (EW-sIgE) levels that will allow us to predict the result of the oral food challenge test (OFC) in the diagnosis of egg white allergy vary by the community where the study is carried out.

ObjectiveThis study aimed to determine the diagnostic values of SPT and EW-sIgE levels in the diagnosis of egg white allergy.

Methods59 patients followed with the diagnosis of egg allergy September 2013 to September 2015 were included in our retrospective cross-sectional study. The patients were investigated in terms of egg and anaphylaxis history or the requirement of the OFC positivity. The demographic, clinical and laboratory findings of the cases were recorded, and they were compared with the patients with the suspected egg allergy but negative OFC (n=47).

ResultsIn the study, for all age groups, the value of 5mm in SPT was found to be significant at 96.4% positive predictive value (PPV) and 97.8% specificity and the value of 5.27kU/L for EW-sIgE was found to be significant at 76% PPV and 86.6% specificity for egg white. The diagnostic power of the SPT for egg white (AUC: 72.2%) was determined to be significantly higher compared to the diagnostic power of the EW-sIgE (AUC: 52.3%) (p<0.05).

ConclusionAlong with the determination of the diagnostic values of communities, the rapid and accurate diagnosis of the children with a food allergy will be ensured, and the patient follow-up will be made easier.

Egg allergy is the second most common food allergy after cow's milk allergy (0.5–2.5%) in childhood age group and it develops with IgE-associated and/or non-associated immune-mediated reaction.1 While egg allergy is often admitted with urticaria and atopic dermatitis complaints during the infancy period, life-threatening or fatal anaphylactic reactions can be observed in some cases.4 Skin tests (skin prick test, patch test), egg-specific IgE (EW-sIgE) and oral challenge tests as a gold standard are used in the diagnosis.2,3 It is essential to verify egg allergy before performing egg elimination due to the importance of the egg containing essential amino acids in infant nutrition. Therefore, it will be useful to determine the diagnostic decision values of induration diameters and egg sIgE levels of the skin prick test which replace the expensive and difficult challenge test, which has the risk of anaphylaxis. Different specific IgE levels with a positive predictive value of 95% have been reported in studies carried out in different centres. Moreover, the diagnostic decision point (DDP) value of sIgE varies depending on country and race.5 This can be caused by the different egg prevalence in the centres where the studies were carried out and the differences in criteria for inclusion in the study, the patient's age and the challenge method. Due to the specified reasons, the fact that each country determines its own diagnostic decision values will ensure the prevention of errors being made in the diagnosis. As far as we know, there has been no such study carried out on this issue in Turkey.

In the present study, it was aimed to determine the skin prick test induration diameters and EW-sIgE diagnostic decision values that can be used in the diagnosis of egg allergy in Turkey. It was also planned to compare the diagnostic decision values obtained in previous studies with the diagnostic decision values that we have found.

Materials and methodsStudy population59 patients followed with the diagnosis of egg allergy (Group I) between September 2013 to September 2015 were included in our retrospective cross-sectional study. For the diagnosis, the patients were investigated in terms of egg and anaphylaxis history or the requirement of the food challenge test positivity. The demographic, clinical and laboratory findings of the cases were recorded, and they were compared with the patients with the suspected egg allergy but negative OFC (Group II, n=47). The local ethics committee approval which was necessary for the study was received.

Skin prick testFor the prick test, the sensitivities were investigated using ALK-Abello A/S, Horsholm, Denmark standard prick test solutions (egg white, milk, wheat, soy, peanut, and fish). Histamine was used as a positive control. The indurations which were 3mm and above according to the negative control were considered as positive.6

MeasurementsThe total serum IgE and egg sIgE levels were measured with UniCAP (Phadia, Uppsala, Sweden) technology. The detection limit was 0.35kU/L for egg sIgE.8

Oral food challenge testThe oral food challenge (OFC) test was applied to other cases except for those children with a history of severe anaphylaxis as the ‘open challenge test’ according to standard guides. 16g of egg was orally given to patients as seven doses in increasing doses by starting from 0.5 to 1g in 15–30min intervals.9

Statistical analysisIn this study, statistical analyses were performed with NCSS (Number Cruncher Statistical System) 2007 Statistical Software (Utah, USA) package programme. In evaluating the data, the independent t-test was used in the comparison of paired groups of variables showing normal distribution and the chi-square test was used in the comparison of the qualitative data in addition to descriptive statistical methods (average, standard deviation). For the determination of the Challenge Test positivity, egg white and egg yolk induration diameters in the skin prick test and the area under the ROC curve for the EW-sIgE level variable were calculated, and the estimation point was determined by calculating the sensitivity, specificity, positive estimation value, negative estimation value, and Likelihood ratio (LR(+)). The results were evaluated at the significance level of p<0.05.

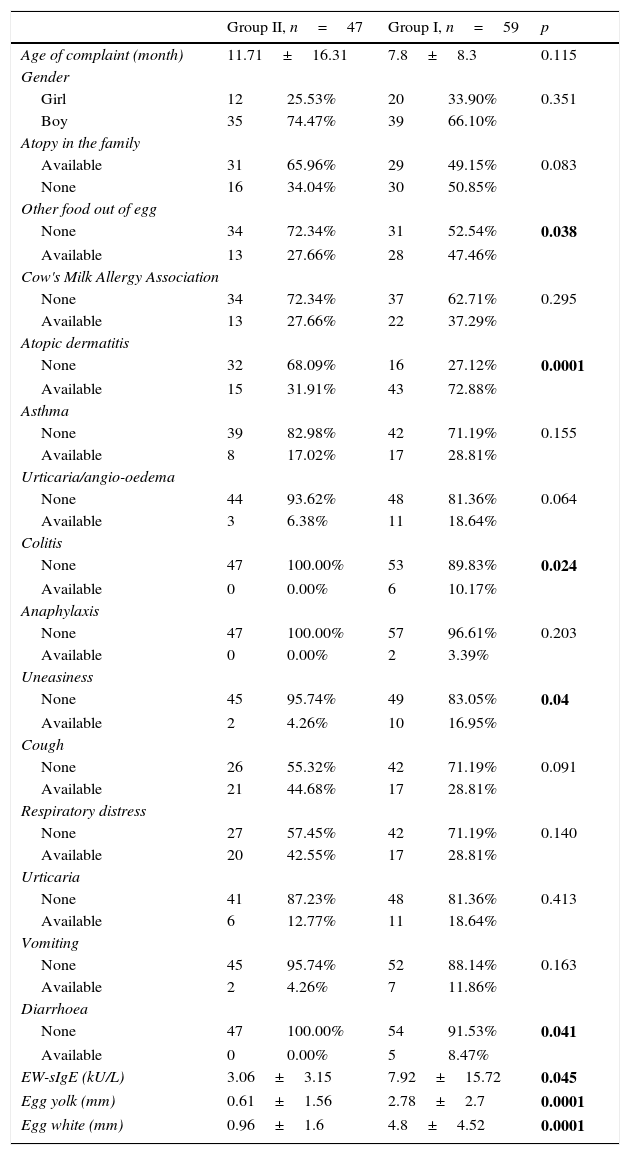

ResultsWhile no difference was observed in terms of the cases’ age of complaint, gender, presence of atopy and accompanying cow's milk allergy (p>0.05), the presence of other food allergy besides eggs, EW-sIgE level, egg yolk and white induration diameters were found to be significantly higher in the group diagnosed with egg allergy (p<0.05). The diagnosis of atopic dermatitis and colitis was found to be significantly higher in the group with egg allergy when the diagnostic distribution of the cases was analysed, and the uneasiness and diarrhoea symptoms were also found to be significantly higher in that group when the symptom distribution was analysed (p<0.05) (Table 1).

Distribution of the demographic, clinical and laboratory features of the groups.

| Group II, n=47 | Group I, n=59 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of complaint (month) | 11.71±16.31 | 7.8±8.3 | 0.115 | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Girl | 12 | 25.53% | 20 | 33.90% | 0.351 |

| Boy | 35 | 74.47% | 39 | 66.10% | |

| Atopy in the family | |||||

| Available | 31 | 65.96% | 29 | 49.15% | 0.083 |

| None | 16 | 34.04% | 30 | 50.85% | |

| Other food out of egg | |||||

| None | 34 | 72.34% | 31 | 52.54% | 0.038 |

| Available | 13 | 27.66% | 28 | 47.46% | |

| Cow's Milk Allergy Association | |||||

| None | 34 | 72.34% | 37 | 62.71% | 0.295 |

| Available | 13 | 27.66% | 22 | 37.29% | |

| Atopic dermatitis | |||||

| None | 32 | 68.09% | 16 | 27.12% | 0.0001 |

| Available | 15 | 31.91% | 43 | 72.88% | |

| Asthma | |||||

| None | 39 | 82.98% | 42 | 71.19% | 0.155 |

| Available | 8 | 17.02% | 17 | 28.81% | |

| Urticaria/angio-oedema | |||||

| None | 44 | 93.62% | 48 | 81.36% | 0.064 |

| Available | 3 | 6.38% | 11 | 18.64% | |

| Colitis | |||||

| None | 47 | 100.00% | 53 | 89.83% | 0.024 |

| Available | 0 | 0.00% | 6 | 10.17% | |

| Anaphylaxis | |||||

| None | 47 | 100.00% | 57 | 96.61% | 0.203 |

| Available | 0 | 0.00% | 2 | 3.39% | |

| Uneasiness | |||||

| None | 45 | 95.74% | 49 | 83.05% | 0.04 |

| Available | 2 | 4.26% | 10 | 16.95% | |

| Cough | |||||

| None | 26 | 55.32% | 42 | 71.19% | 0.091 |

| Available | 21 | 44.68% | 17 | 28.81% | |

| Respiratory distress | |||||

| None | 27 | 57.45% | 42 | 71.19% | 0.140 |

| Available | 20 | 42.55% | 17 | 28.81% | |

| Urticaria | |||||

| None | 41 | 87.23% | 48 | 81.36% | 0.413 |

| Available | 6 | 12.77% | 11 | 18.64% | |

| Vomiting | |||||

| None | 45 | 95.74% | 52 | 88.14% | 0.163 |

| Available | 2 | 4.26% | 7 | 11.86% | |

| Diarrhoea | |||||

| None | 47 | 100.00% | 54 | 91.53% | 0.041 |

| Available | 0 | 0.00% | 5 | 8.47% | |

| EW-sIgE (kU/L) | 3.06±3.15 | 7.92±15.72 | 0.045 | ||

| Egg yolk (mm) | 0.61±1.56 | 2.78±2.7 | 0.0001 | ||

| Egg white (mm) | 0.96±1.6 | 4.8±4.52 | 0.0001 | ||

Egg white-specific IgE (EW-sIgE).

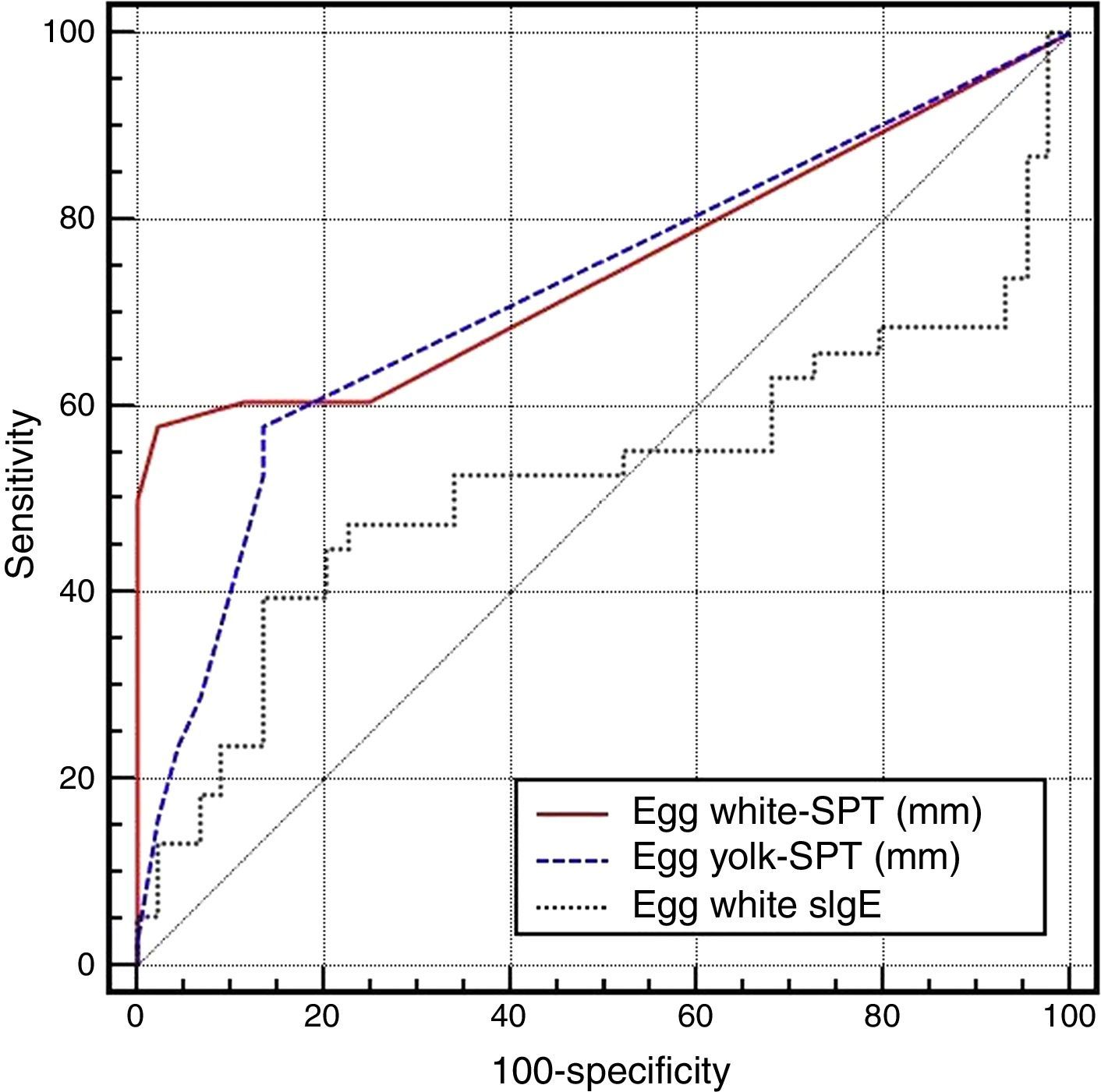

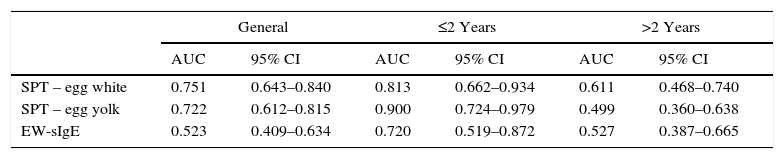

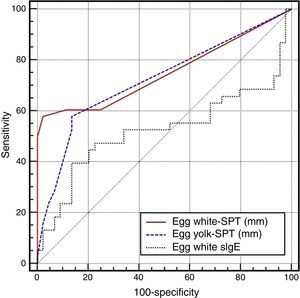

On the basis of the gold standard challenge test or egg and anaphylaxis history, in the skin prick test for the general patient group, while the area under the ROC curve was found to be 0.751 (0.643–0.840) for the egg white induration diameter, it was found to be 0.722 (0.612–0.815) for the egg yolk and 0.523 (0.409–0.634) for the EW-sIgE level (p<0.05), and the area under the ROC curve was found out to be statistically significantly low for EW-sIgE (p<0.05) (Fig. 1) (Table 2).

Comparison of the ROC curves for the egg skin prick test and egg white-specific IgE levels.

| General | ≤2 Years | >2 Years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | 95% CI | AUC | 95% CI | AUC | 95% CI | |

| SPT – egg white | 0.751 | 0.643–0.840 | 0.813 | 0.662–0.934 | 0.611 | 0.468–0.740 |

| SPT – egg yolk | 0.722 | 0.612–0.815 | 0.900 | 0.724–0.979 | 0.499 | 0.360–0.638 |

| EW-sIgE | 0.523 | 0.409–0.634 | 0.720 | 0.519–0.872 | 0.527 | 0.387–0.665 |

| Pairwise comparison of the ROC curves | General | ≤2 Years | >2 Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| p | p | p | |

| SPT – egg white/SPT – egg yolk | 0.558 | 0.456 | 0.239 |

| SPT – egg white/EW-sIgE | 0.002 | 0.358 | 0.457 |

| SPT – egg yolk/EW-sIgE | 0.012 | 0.213 | 0.812 |

Egg white-specific IgE (EW-sIgE).

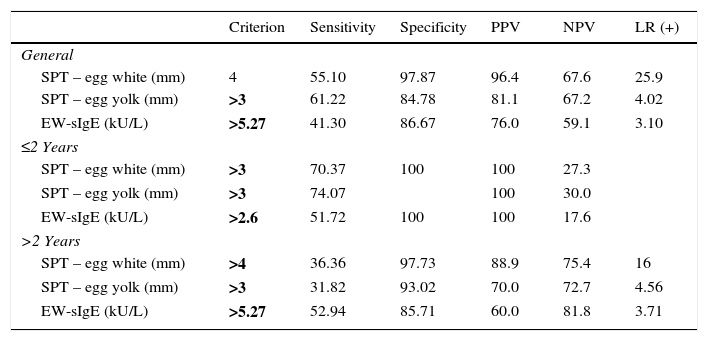

The diagnostic decision values of the skin prick test and EW-sIgE levels according to age groups were found as >4mm for the egg white induration diameter and as >3mm for egg yolk in DPT in the general patient group, and the diagnostic cut-off value was found as >5.27kU/L for the EW-sIgE level. In cases aged two and below, the diagnostic decision values were found as >3mm, >3mm and >2.6kU/L for egg white, egg yolk and EW-sIgE level, respectively, in DPT. In cases above the age of two, the diagnostic decision values were found as >4mm, >3mm and >5.27kU/L for egg white, egg yolk and EW-sIgE level, respectively, in DPT (Table 3).

Diagnostic decision points of the egg skin prick test and egg white specific IgE levels by age groups.

| Criterion | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | LR (+) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | ||||||

| SPT – egg white (mm) | 4 | 55.10 | 97.87 | 96.4 | 67.6 | 25.9 |

| SPT – egg yolk (mm) | >3 | 61.22 | 84.78 | 81.1 | 67.2 | 4.02 |

| EW-sIgE (kU/L) | >5.27 | 41.30 | 86.67 | 76.0 | 59.1 | 3.10 |

| ≤2 Years | ||||||

| SPT – egg white (mm) | >3 | 70.37 | 100 | 100 | 27.3 | |

| SPT – egg yolk (mm) | >3 | 74.07 | 100 | 30.0 | ||

| EW-sIgE (kU/L) | >2.6 | 51.72 | 100 | 100 | 17.6 | |

| >2 Years | ||||||

| SPT – egg white (mm) | >4 | 36.36 | 97.73 | 88.9 | 75.4 | 16 |

| SPT – egg yolk (mm) | >3 | 31.82 | 93.02 | 70.0 | 72.7 | 4.56 |

| EW-sIgE (kU/L) | >5.27 | 52.94 | 85.71 | 60.0 | 81.8 | 3.71 |

Egg white-specific IgE (EW-sIgE).

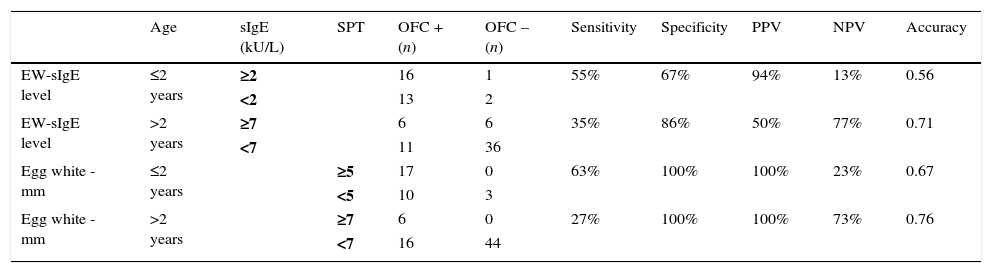

When the diagnostic decision values obtained in our study group were compared with the levels obtained in the literature, they were found to be significant at 100% PPV and 100% specificity for the egg white induration diameters in DPT. The egg white-sIgE level was found to be significant at 94% PPV and 67% specificity in cases aged below two years and at 50% PPV and 86% specificity in cases aged above two years (Table 4).

Evaluation of the results of the study group according to the diagnostic decision values obtained in previous studies [15,18].

| Age | sIgE (kU/L) | SPT | OFC + (n) | OFC – (n) | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EW-sIgE level | ≤2 years | ≥2 | 16 | 1 | 55% | 67% | 94% | 13% | 0.56 | |

| <2 | 13 | 2 | ||||||||

| EW-sIgE level | >2 years | ≥7 | 6 | 6 | 35% | 86% | 50% | 77% | 0.71 | |

| <7 | 11 | 36 | ||||||||

| Egg white -mm | ≤2 years | ≥5 | 17 | 0 | 63% | 100% | 100% | 23% | 0.67 | |

| <5 | 10 | 3 | ||||||||

| Egg white -mm | >2 years | ≥7 | 6 | 0 | 27% | 100% | 100% | 73% | 0.76 | |

| <7 | 16 | 44 |

Egg white-specific IgE (EW-sIgE).

In the present study in which it was aimed to determine the diagnostic decision values of the DPT induration diameters and EW-sIgE levels in the diagnosis of egg allergy, we found out that egg white DPT was more diagnostic than sIgE for all age groups. The induration diameter >4mm above for egg white was found to be significant at 96.4% positive predictive value (PPV) and 97.8% specificity in DPT, the value of 5.27kU/L for the EW-sIgE level was found to be significant at 76% positive predictive value (PPV) and 86.6% specificity.

The history of the patients, clinical findings, the values of egg sp-IgE and the skin prick test are used in the diagnosis of egg-related IgE-associated allergy. Besides, the standardised double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge test is the gold standard in the diagnosis of egg allergy, and it is often applied for diagnostic purposes and to determine the development of tolerance in cases when the history and DPT results/EW-sIgE levels are not compatible with each other or it is estimated that EW-sIgE values or DPT results are over egg allergy with 50% accuracy.7,8 In the studies carried out, serum EW-sIgE values have been demonstrated to be correlated with the oral food challenge test result.9 Furthermore, 95% PPV has been determined for EW-sIgE levels in the studies and it is commonly used in the clinic.10–12 However, some patients with the EW-sIgE antibody levels which are higher than the estimated decision point values show no clinical symptoms and this is also true vice versa.13,14 Therefore, OFC is the most reliable indicator of hypersensitivity when the EW-sIgE measurements are inconsistent with the clinical history.15

In the present study, the diagnostic value for EW-sIgE≥5.27kU/L in predicting the egg allergy determined by the food challenge test (with 41.3% sensitivity and 86.6% specificity) and the egg white induration diameter above >4mm in DPT (with 55.1% sensitivity and 97.8% specificity) was found to be statistically significant. The diagnostic predictive value we have found is different from some studies in the literature. In the study carried out by Sampson et al., it was determined that 7kU/L EW-sIgE level had 95% PPV in children older than two, and 2kU/L level had 95 PPV% in children aged two or below.7,15–18 It has been reported that the fact that the induration diameter is ≥7mm for egg white in those above the age of two and is ≥5mm in those below the age of two in DPT increases the possibility of showing food allergy.18 In a recent study carried out by Kim et al.20 in the literature, it has been reported that there is a 90% risk of reaction if the EW-sIgE level is 28.1kU/L in children below the age of two and is 22.9kU/L in children above the age of two. Osterballe et al.13 reported the diagnostic decision point as 1.5kU/L for egg allergy. A Spanish study presented 2.5kU/L as the 90% diagnostic decision point (DDP) for CM.7 A German study demonstrated that the diagnostic values for 95% probability of allergy were 10kU/L for egg.19 In a Japanese study, the 95% DDPs for EW and CM were reported as 25.5 and 50.9kU/L, respectively.10 We think that the inclusion of populations covering different age groups, the diversity of study methodologies (such as retrospective/prospective, open/blind) and the difference in the standardisation of diagnostic procedures can be the reasons for why EW-sIgE threshold values used in predicting the food allergy are different among studies.

When the diagnostic decision values obtained in the studies carried out by Sampson et al.15 were compared with the diagnostic decision values obtained in the patients followed in our region, the egg white induration diameters were found to be significant at 100% PPV and 100% specificity in DPT. The EW-sIgE level was found to be significant in cases below the age of two at 94% PPV and 67% specificity and in cases above the age of two at 50% PPV and 86% specificity. Therefore, we think that the use of the diagnostic decision values obtained in the regional studies in cases evaluated with the pre-diagnosis of egg allergy will prevent the mistakes in the diagnosis.

The ROC curve helps to find the optimal threshold value by analysing the sensitivity and specificity changes of the threshold value that determines the functionality of a test. In the present study, while PPV value of EW-sIgE >5.27kU/L threshold value was found as 96.4%, its NPV value was found as 67.6%. Sampson et al. found 38% NPV and 98% PPV for 7kU/L threshold level for EW-sIgE in predicting the positive food challenge test in 100 children admitted with the suspected food allergy.21 Different results obtained in different studies may be associated with the prevalence of egg allergy in the populations included in the study. The prevalence of the disease in the populations included in the study affects the PPV and NPV values of the disease; PPV increases but NPV value decreases in populations in which the prevalence of the disease is high. For these reasons, we believe that it will be suitable for each region to use the diagnostic decision values obtained from the patients followed in their own region since NPV and PPV values vary in countries.

Regarding the limitations of the present study, firstly, some data could not be reached at the sufficient level because our study is retrospective. Secondly, the oral challenge tests applied in the study are not double-blind placebo-controlled. However, it has been stated in many guidelines that there is no need to perform double-blind in the infant period. Thirdly, the egg yolk specific IgE levels are lacking in patients whose OFC test is negative. Therefore, the threshold values related to the egg yolk sIgE could not be calculated.

Regarding the contributions of the present study, it is the first study in our country investigating the serum EW-sIgE level in making a diagnosis of egg allergy and predicting the result of the food challenge test by using standardised methods in children with the suspected egg white allergy. There may be no need to perform the oral challenge test in some patients by detecting the diagnostic PPV values and using them in the clinic. The different results obtained in the studies show us that we need to use these tests more accurately and more efficiently in the diagnosis of egg white allergy. Along with the present study, we believe that the possible mistakes in the diagnosis of patients will be prevented by finding the diagnostic decision values in patients followed in our country.

In conclusion, all tests should be evaluated together in the diagnosis of egg allergy since the tests except for the challenge test are not adequate in making diagnosis alone. The egg allergy diagnostic studies will be strengthened by determining the diagnostic values of EW-sIgE levels and the induration diameters in DPT, and they will be guiding in predicting the results of the food challenge test by being evaluated together with the history. The unnecessary dietary restrictions which will negatively affect the child's growth and development will be prevented and also the morbidity to be caused by food allergy will be avoided by making an accurate diagnosis.

Funding sourceNo external funding was secured for this study.

Financial disclosureThe authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Trial registrationNot applicable.

Contributors’ statement pageNacaroglu, Hikmet Tekin; literature search, study design, data collection, manuscript preparation/editing, final manuscript approval.

Bahceci Erdem, Semiha literature search, study design, data collection, manuscript preparation/editing, final manuscript approval.

Karaman, Sait; literature search, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation.

Dogan, Döne; literature search, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation.

Unsal Karkıner, Canan Sule; literature search, manuscript preparation/editing, data analysis.

Toprak Kanık, Esra; literature search, study design, final manuscript approval.

Can, Demet; literature search, manuscript preparation/editing, data analysis, final manuscript approval.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Approval by the local ethics committee was granted.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.