Although the prevalence of sensitization to fungi is not precisely known, it can reach 50% in inner cities and has been identified as a risk factor in the development of asthma. Whereas the prevalence of allergic diseases is increasing, it is unclear whether the same occurs with sensitization to fungi.

Patients and methodsA retrospective study was performed at the “Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez”. From skin tests taken between 2004 and 2015, information was gathered about Alternaria alternata, Aspergillus fumigatus, Candida albicans, Cladosporium herbarum, Mucor mucedo and Penicillium notatum. The participating patients were 2–18 years old, presented some type of allergic condition, and underwent immediate hypersensitivity tests to the fungi herein examined. Descriptive analysis and chi-squared distribution were used.

ResultsOf the 8794 patients included in the study, 14% showed a negative result to the entire panel of environmental allergens. The remaining 7565 individuals displayed sensitization to at least one fungus, which most frequently was Aspergillus, with a rate of 16.8%. When the patients were divided into age groups, the same trend was observed. The highest percentage of sensitization (58%) toward at least one type of fungus was found in 2014, and the lowest percentage (49.8%) in 2008.

ConclusionThe rate of sensitization to at least one type of fungus was presently over 50%, higher than that detected in other medical centers in Mexico. This rate was constant over the 11-year study, and Aspergillus exhibited the greatest frequency of sensitization among the patients.

Fungi are eukaryotic organisms that live as saprophytes, parasites or symbionts in their plant or animal hosts. These ubiquitous organisms, which grow in intra- and extra-domiciliary environments and in almost any substrate, exhibit optimal growth at a temperature between 18 and 32°C.1 Of the more than 100,000 existing species, there are more than 80 genus (especially in the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota phyla) known to cause type 1 allergies in susceptible individuals.2

Penicillium, Aspergillus, Cladosporium and Alternaria are reportedly the most prevalent fungal aeroallergens worldwide.3 Spores from the former two genera are present all year round,4 whereas Cladosporium and Alternaria tend to show seasonal peaks, primarily during the rainy season and from April to October.5

Although the prevalence of sensitization to fungi is not precisely known, it is estimated to vary between 3% and 10% among the general population (depending to a large extent on the climatic conditions of the area under study),4 and can reach 50% in the inner cities.6

Sensitization to fungi has been identified as a risk factor for the development of asthma.7,8 Elevated spore levels in the atmosphere correlate with an increased number of hospitalizations and deaths from asthma9 as well as a greater risk of developing rhinitis.10

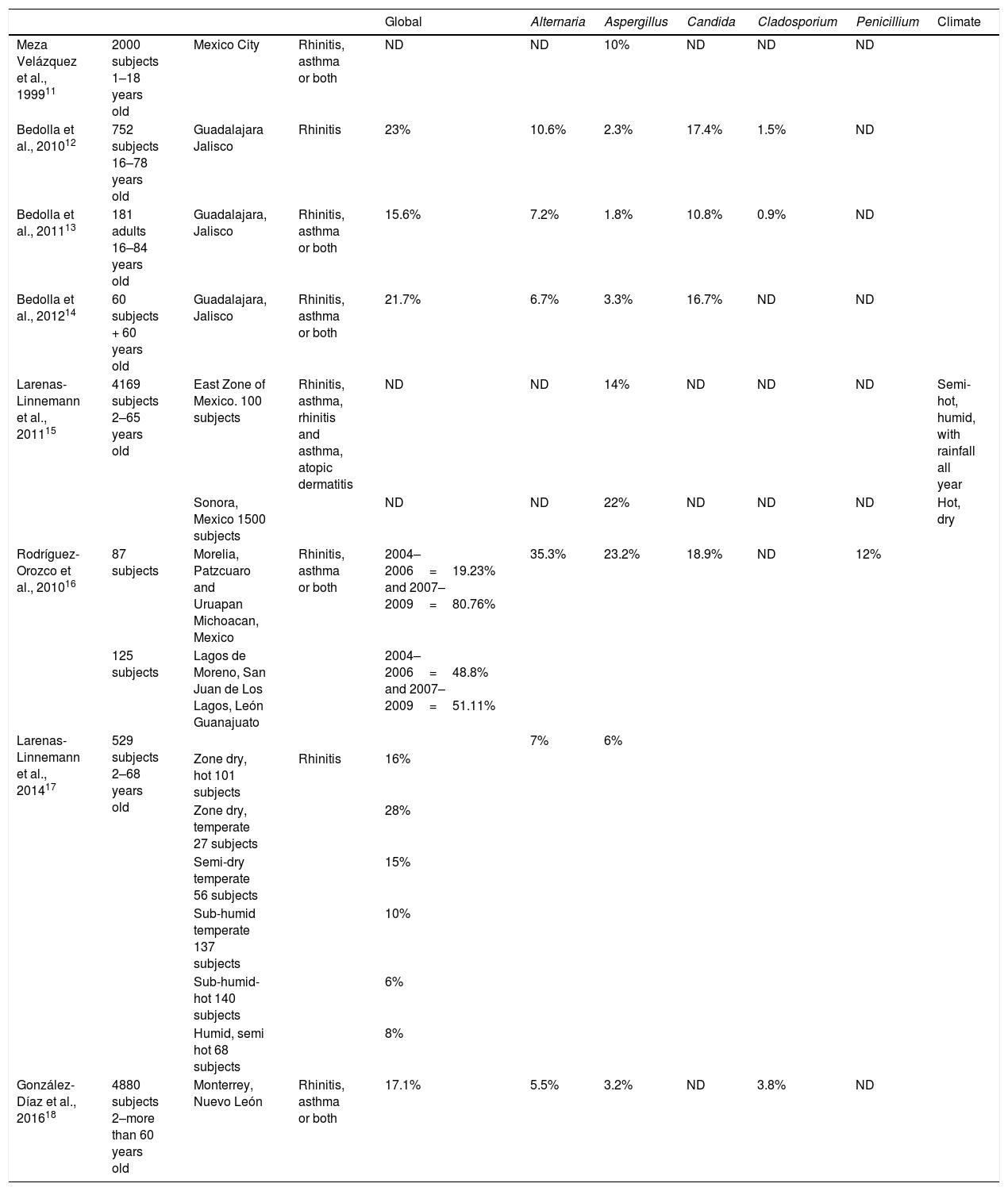

In Mexico, several authors have investigated the rate of sensitization to such aeroallergens in cross-sectional studies, with results varying according to the particular region in question (Table 1).11–18 Within the 1.9 million square kilometers of land area in this North American country, the average temperatures range from 10 to 26°C (except for the most extreme zones representing 7% of the territory).19 One area of special importance is Mexico City and the surrounding metropolitan area. Located in a large valley at a high altitude, the city has a population of over 20 million people. The climate is sub-humid with an average temperature of 16°C, reaching 25°C between March and May, and descending as low as 5°C in January. The rainy season is long, usually starting in May and ending in October.19

Prevalence of fungi sensitization in Mexico.

| Global | Alternaria | Aspergillus | Candida | Cladosporium | Penicillium | Climate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meza Velázquez et al., 199911 | 2000 subjects 1–18 years old | Mexico City | Rhinitis, asthma or both | ND | ND | 10% | ND | ND | ND | |

| Bedolla et al., 201012 | 752 subjects 16–78 years old | Guadalajara Jalisco | Rhinitis | 23% | 10.6% | 2.3% | 17.4% | 1.5% | ND | |

| Bedolla et al., 201113 | 181 adults 16–84 years old | Guadalajara, Jalisco | Rhinitis, asthma or both | 15.6% | 7.2% | 1.8% | 10.8% | 0.9% | ND | |

| Bedolla et al., 201214 | 60 subjects + 60 years old | Guadalajara, Jalisco | Rhinitis, asthma or both | 21.7% | 6.7% | 3.3% | 16.7% | ND | ND | |

| Larenas-Linnemann et al., 201115 | 4169 subjects 2–65 years old | East Zone of Mexico. 100 subjects | Rhinitis, asthma, rhinitis and asthma, atopic dermatitis | ND | ND | 14% | ND | ND | ND | Semi-hot, humid, with rainfall all year |

| Sonora, Mexico 1500 subjects | ND | ND | 22% | ND | ND | ND | Hot, dry | |||

| Rodríguez-Orozco et al., 201016 | 87 subjects | Morelia, Patzcuaro and Uruapan Michoacan, Mexico | Rhinitis, asthma or both | 2004–2006=19.23% and 2007–2009=80.76% | 35.3% | 23.2% | 18.9% | ND | 12% | |

| 125 subjects | Lagos de Moreno, San Juan de Los Lagos, León Guanajuato | 2004–2006=48.8% and 2007–2009=51.11% | ||||||||

| Larenas-Linnemann et al., 201417 | 529 subjects 2–68 years old | 7% | 6% | |||||||

| Zone dry, hot 101 subjects | Rhinitis | 16% | ||||||||

| Zone dry, temperate 27 subjects | 28% | |||||||||

| Semi-dry temperate 56 subjects | 15% | |||||||||

| Sub-humid temperate 137 subjects | 10% | |||||||||

| Sub-humid-hot 140 subjects | 6% | |||||||||

| Humid, semi hot 68 subjects | 8% | |||||||||

| González-Díaz et al., 201618 | 4880 subjects 2–more than 60 years old | Monterrey, Nuevo León | Rhinitis, asthma or both | 17.1% | 5.5% | 3.2% | ND | 3.8% | ND |

Since the prevalence of allergic diseases is increasing, it is of interest to determine whether the same pattern is taking place in terms of sensitization to indoor allergens such as fungi. Rodriguez-Orozco et al. documented an alarming growth in sensitization to fungi,16 but to our knowledge no other reports exist based on longitudinal studies.

The objective of the current investigation, conducted in a hospital of Mexico City and covering 11 years (2004 to 2015), was to determine the annual rate of sensitization to Alternaria alternata, Aspergillus fumigatus, Candida albicans, Cladosporium herbarum, Mucor mucedo and Penicillium notatum in children and adolescents with asthma, rhinitis and/or eczema. Changes in sensitization from year to year were also analyzed.

Material and methodsA retrospective study encompassing an 11-year period (January 2004 to April 2015) was conducted in the Allergy and Clinical Immunology Department of the “Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez”. Skin tests were carried out by physicians and chemists to detect the presence of A. alternata, A. fumigatus, C. albicans, C. herbarum, M. mucedo and P. notatum. All patients included herein were 2–18 years old and presented asthma, rhinitis and/or eczema, which require a skin-prick test (SPT) in compliance with current guidelines. After the clinical history was reviewed by a certified allergist and immunologist, subjects who met the criteria had a skin-prick test performed against inhalants (with previously signed consent and assent). The aforementioned indoor allergens were included. Patients were mainly from Mexico City and the surrounding metropolitan area. For each patient, both demographic information and the referring diagnosis were reviewed. The protocol was approved by the Ethics, Research and Biosafety Committees at the hospital (protocol number HIM/2015/045) and complied with institutional and international guidelines.

During the entire study, skin prick tests were carried out with IPI Assac® extracts. These have been standardized in the same way since 1999 and commercialized as A. alternata UBE/ml (equivalent biologic unit), A. fumigatus PNU/ml (protein nitrogen units), C. albicans UEP/ml, C. herbarum PNU/ml, M. mucedo PNU/ml and P. notatum UEP/ml.

We utilized the SPT protocol recommended by the Global Allergy and Asthma European Network, the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI).20 Allergen extracts were stored at 2–8°C when not in use. The medications taken by patients during the weeks previous to the SPT were recorded with the aim of avoiding false positive results. Tests were applied on the upper back or on the volar surface of the forearm, at least 2–3cm away from the wrist and the antecubital fossa. Histamine (10mg/ml) and saline solutions were employed as positive and negative controls, respectively.

The skin area was marked with a pen, and tests were made 2cm apart from each other. After placing a drop of each test solution on the skin (in the same order for all subjects), a prick was immediately made with a single-headed metal lancet without causing bleeding. The outcome was registered 15min later. The largest diameter and the orthogonal diameter of the wheal were measured, and the following value was calculated: largest diameter+perpendicular diameter/2. Wheals having a diameter more than 3mm larger than the negative control were considered to be positive reactions. Each panel comprised a total of 27 environmental allergens, which included six types of mold (A. alternata, A. fumigatus, C. albicans, C. herbarum, M. mucedo and P. notatum), four animal skin dander extracts (horse, cat hair, dog, and chicken feathers), seven types of weeds (Ambrosia trifida, Artemisa vulgaris, Chenopodium album, Helianthus annus, Plantago lanceolata, Rumex spp and Salsola kal), three grasses (Lolium perenne, Phleum pretense and Cynodon dactylon) and four trees (Fraxinus excelsior, Quercus robur, Schinus molle and Ligustrum vulgare), as well as cockroach and mite extracts.

In accordance with the aims of the current investigation, descriptive statistics were carried out to obtain the rate of sensitization and the 95% CI of hypersensitivity tests to A. alternata, A. fumigatus, C. albicans, C. herbarum, M. mucedo and P. notatum. The results were analyzed by intra- and inter-group chi-squared (χ2) distribution of the rate of sensitization, similar to the methodology employed in other studies around the country. The differences occurring from year to year were also examined over the 11-year period.

ResultsOf the total of 8794 patients in the study (2–18 years old, mean age 7.9±3.7 years), 41.6% (95% CI 40–42) were from Mexico City, 51.6% from the surrounding metropolitan area in Mexico State (95% CI 50–52), and 6.7% from other areas of the country (95% CI 6–7).

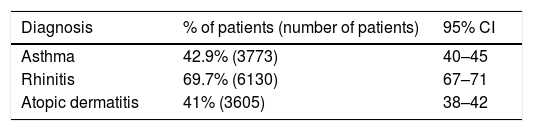

The most frequent diagnosis was allergic rhinitis, followed by asthma and atopic dermatitis (Table 2). The diagnoses were made by a pediatric allergist in accordance with current guidelines: Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA), Allergic Rhinitis and its impact in Asthma (ARIA), and Disease management of atopic dermatitis: Practice Parameter. The expected overlap of these diseases in atopic patients can be appreciated.

Distribution of patients according to reported diagnosis, n=8794.

| Diagnosis | % of patients (number of patients) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Asthma | 42.9% (3773) | 40–45 |

| Rhinitis | 69.7% (6130) | 67–71 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 41% (3605) | 38–42 |

Note: The diagnoses were made by a pediatric allergist according to ongoing guides: Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA); Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA), disease management of atopic dermatitis: practice parameter. No differences found on patients’ gender.

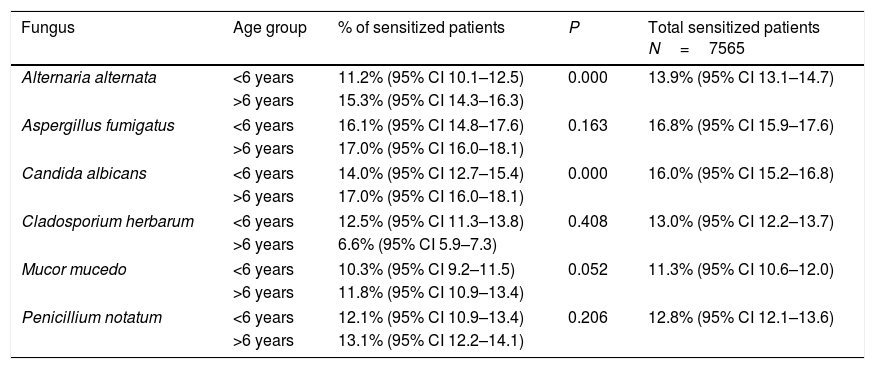

Among the 8794 tests, 14% (95% CI 13–14.8) were negative to the entire panel of fungi. Of the remaining 7565 tests, the greatest rate of sensitization was evidenced for Aspergillus at 16.8% (CI 95% 15.9–17.6). Upon dividing the patients into age groups, the same trend was encountered, with sensitization to Aspergillus being the most frequently detected in both groups of patients, both above and below the age of six. Sensitization to Candida was also significant in the elder age group (Table 3).

Percentage of sensitization to panel of six fungi.

| Fungus | Age group | % of sensitized patients | P | Total sensitized patients N=7565 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternaria alternata | <6 years | 11.2% (95% CI 10.1–12.5) | 0.000 | 13.9% (95% CI 13.1–14.7) |

| >6 years | 15.3% (95% CI 14.3–16.3) | |||

| Aspergillus fumigatus | <6 years | 16.1% (95% CI 14.8–17.6) | 0.163 | 16.8% (95% CI 15.9–17.6) |

| >6 years | 17.0% (95% CI 16.0–18.1) | |||

| Candida albicans | <6 years | 14.0% (95% CI 12.7–15.4) | 0.000 | 16.0% (95% CI 15.2–16.8) |

| >6 years | 17.0% (95% CI 16.0–18.1) | |||

| Cladosporium herbarum | <6 years | 12.5% (95% CI 11.3–13.8) | 0.408 | 13.0% (95% CI 12.2–13.7) |

| >6 years | 6.6% (95% CI 5.9–7.3) | |||

| Mucor mucedo | <6 years | 10.3% (95% CI 9.2–11.5) | 0.052 | 11.3% (95% CI 10.6–12.0) |

| >6 years | 11.8% (95% CI 10.9–13.4) | |||

| Penicillium notatum | <6 years | 12.1% (95% CI 10.9–13.4) | 0.206 | 12.8% (95% CI 12.1–13.6) |

| >6 years | 13.1% (95% CI 12.2–14.1) | |||

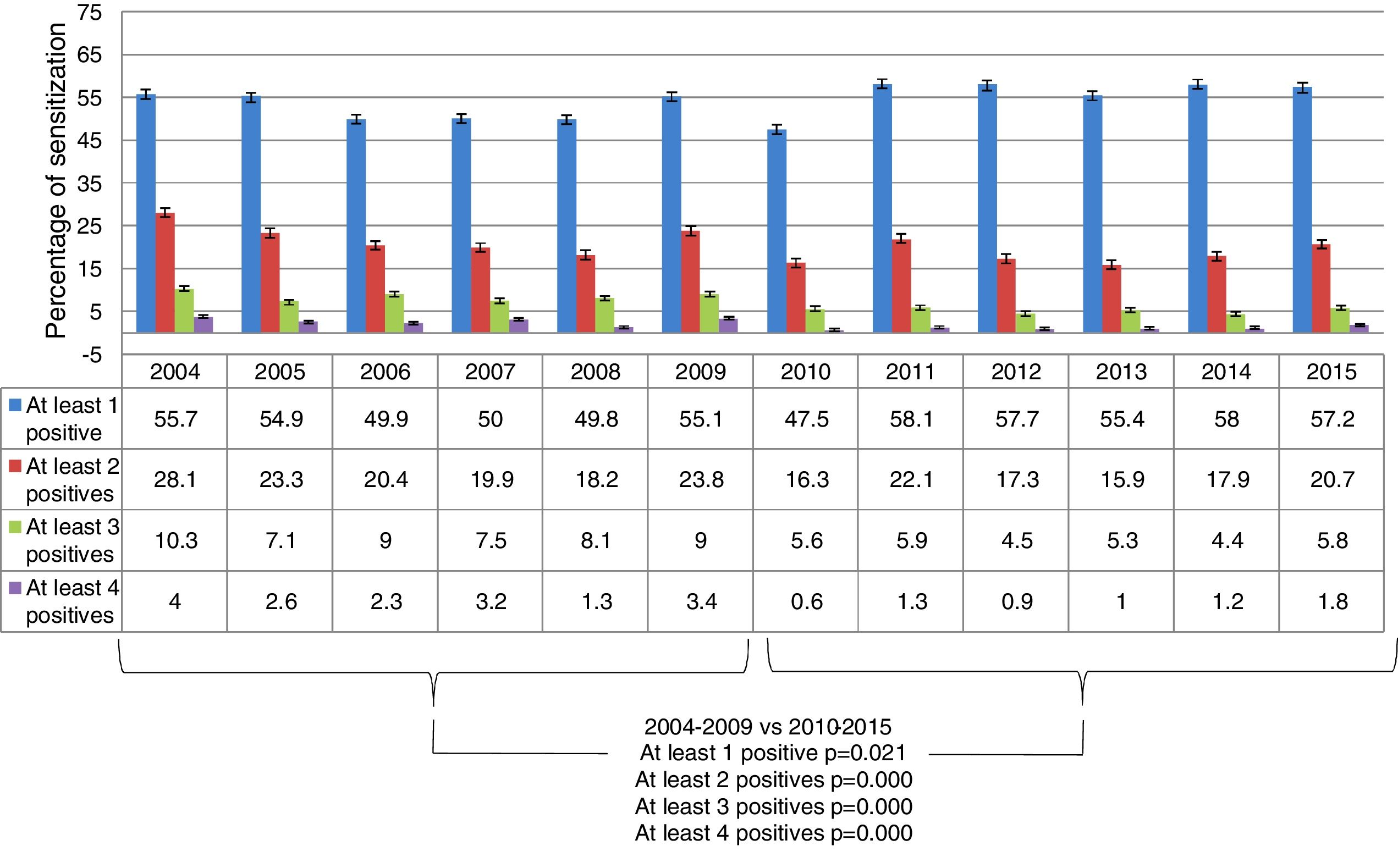

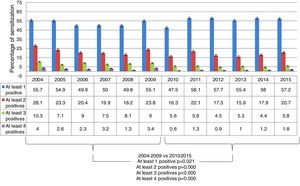

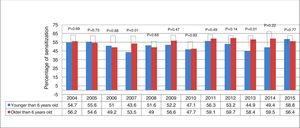

When all the fungi were considered together, around 50% of the patients showed sensitization to at least one fungus every year. The highest percentage (58%; CI 95% 54.6–63.5) was detected in 2014, and the lowest percentage (49.8%; CI 95% 44.8–54.8) in 2008. A decrease occurred in the number of patients with test results positive to at least 2, 3 and 4 fungi from 2004–2009 and 2010–2015 (Fig. 1).

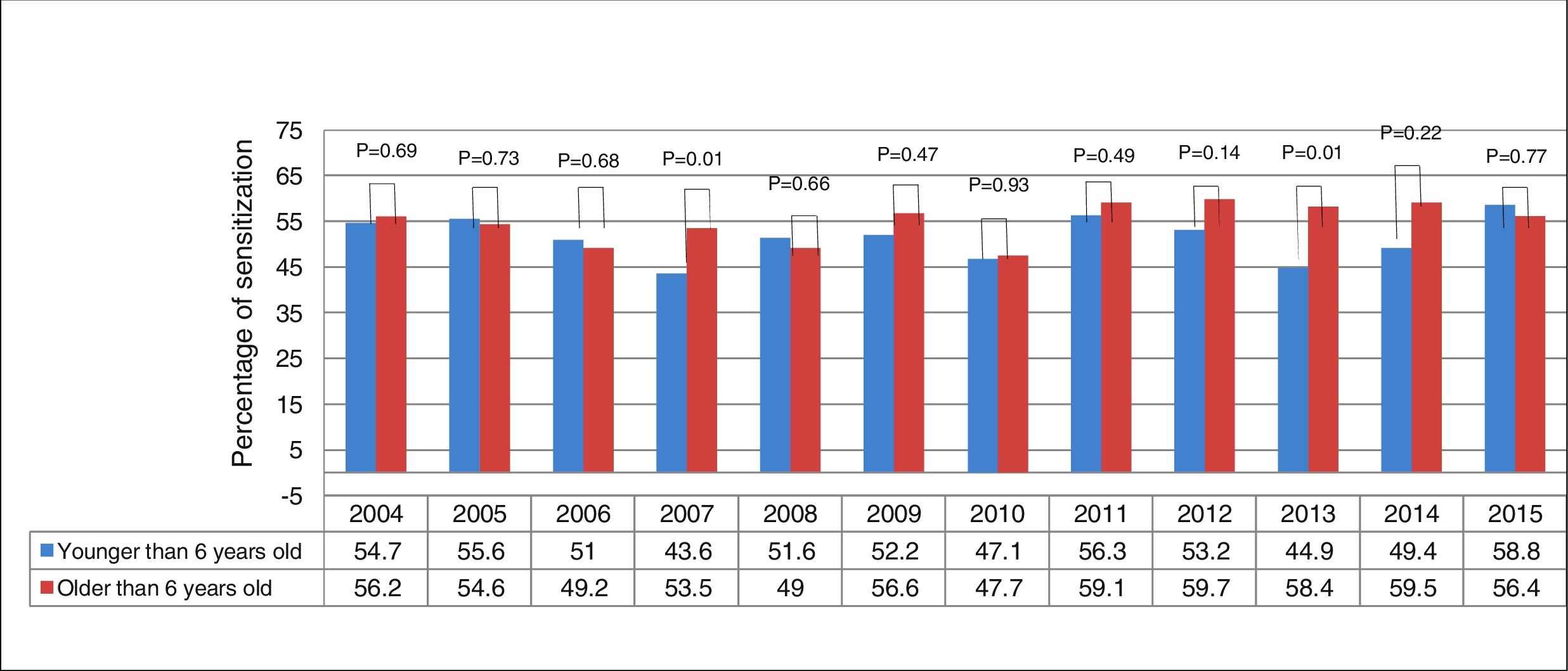

Of the tests carried out presently, 34% (CI 95% 33–35) were performed on patients under the age of six. Upon comparing sensitization in children under and over six years of age, the overall percentage (for all fungi) was similar between the two groups. The only significant difference between the two groups was observed in 2013, with an elevated level in the elder group of patients (Fig. 2). The selection of a cut-off age of six was made based on Moral et al.,21 who reported greater sensitization after this age.

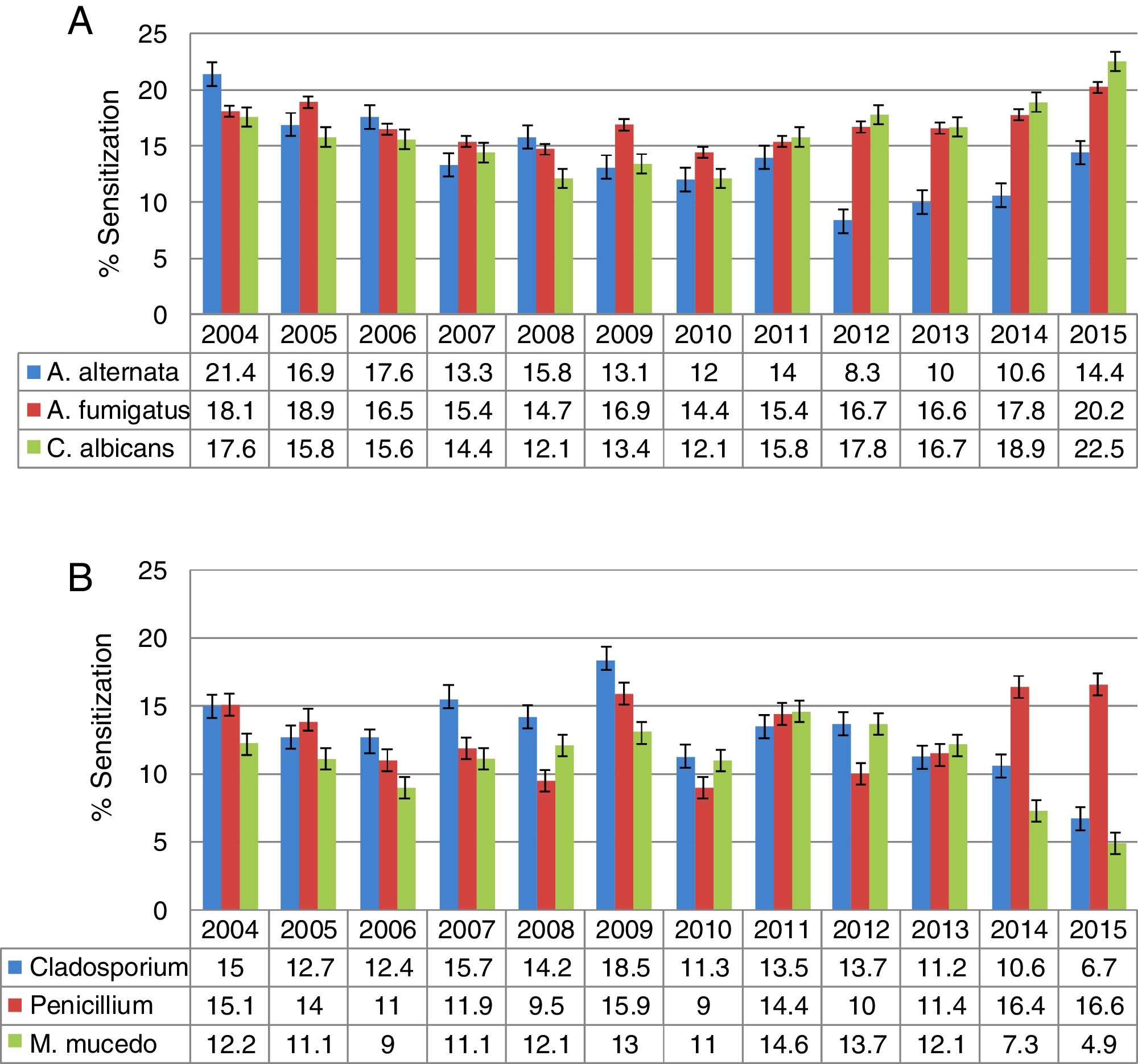

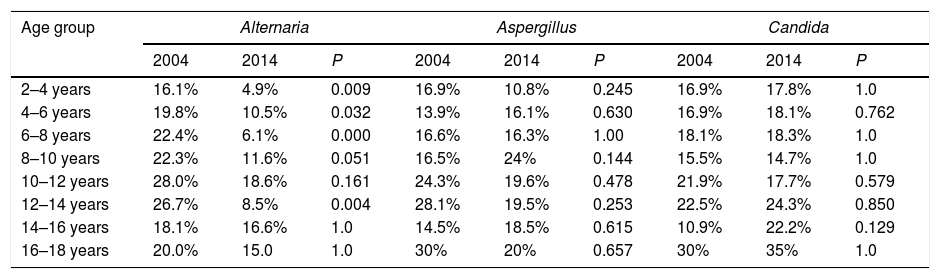

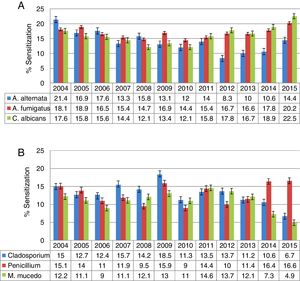

When stratifying by age, a higher percentage of sensitization was shown for the group from 16 to 18 years of age, particularly in relation to Alternaria, Candida and Cladosporium. The analysis of positive skin test results per year is illustrated in Fig. 3. Upon making a comparison by age and year, a general decrease was found over time in the percentage of sensitization to Alternaria, Cladosporium, Mucor and Aspergillus, and an increase for Candida and Penicillium (Table 4).

Comparison of percentage of sensitization to different fungi separated by age in 2004 vs. 2014.

| Age group | Alternaria | Aspergillus | Candida | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2014 | P | 2004 | 2014 | P | 2004 | 2014 | P | |

| 2–4 years | 16.1% | 4.9% | 0.009 | 16.9% | 10.8% | 0.245 | 16.9% | 17.8% | 1.0 |

| 4–6 years | 19.8% | 10.5% | 0.032 | 13.9% | 16.1% | 0.630 | 16.9% | 18.1% | 0.762 |

| 6–8 years | 22.4% | 6.1% | 0.000 | 16.6% | 16.3% | 1.00 | 18.1% | 18.3% | 1.0 |

| 8–10 years | 22.3% | 11.6% | 0.051 | 16.5% | 24% | 0.144 | 15.5% | 14.7% | 1.0 |

| 10–12 years | 28.0% | 18.6% | 0.161 | 24.3% | 19.6% | 0.478 | 21.9% | 17.7% | 0.579 |

| 12–14 years | 26.7% | 8.5% | 0.004 | 28.1% | 19.5% | 0.253 | 22.5% | 24.3% | 0.850 |

| 14–16 years | 18.1% | 16.6% | 1.0 | 14.5% | 18.5% | 0.615 | 10.9% | 22.2% | 0.129 |

| 16–18 years | 20.0% | 15.0 | 1.0 | 30% | 20% | 0.657 | 30% | 35% | 1.0 |

| Age group | Cladosporium | Penicillium | Mucor | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2014 | P | 2004 | 2014 | P | 2004 | 2014 | P | |

| 2–4 years | 13.5% | 12.8% | 1.000 | 16.1% | 19.8% | 0.485 | 9.3% | 4.9% | 0.299 |

| 4–6 years | 12.5% | 11.5% | 0.86 | 18.3% | 15.5% | 0.537 | 10.2% | 3.1% | 0.016 |

| 6–8 years | 14.4% | 8.8% | 0.144 | 17.3% | 16.3% | 0.875 | 10.1% | 8.8% | 0.840 |

| 8–10 years | 20.3% | 6.2% | 0.003 | 12.6% | 16.2% | 0.457 | 16.5% | 8.5% | 0.107 |

| 10–12 years | 17.0% | 11.2% | 0.289 | 3.8% | 11.2% | 0.630 | 13.4% | 11.2% | 0.660 |

| 12–14 years | 16.9% | 12.2% | 0.491 | 16.9% | 19.5% | 0.834 | 21.1% | 8.5% | 0.037 |

| 14–16 years | 12.7% | 12.9% | 1.0 | 12.7% | 20.3% | 0.313 | 5.4% | 7.4% | 0.716 |

| 16–18 years | 10% | 15.0% | 1.0 | 20% | 15% | 1.0 | 30% | 10% | 3.0 |

Exposure to fungal spores and mycelial cells has become a growing health problem. Prolonged contact with these allergens can cause not only the pathologies associated with allergies, but also an extensive panel of other diseases because they colonize the organism and damage airways. Such damage is due to the production of toxins, proteases, enzymes and volatile organic compounds.1

Although exposure to fungi occurs primarily in outdoor environments, fungal spores sometimes penetrate indoor areas as well. In the presence of high humidity, some fungi can even grow on surfaces and materials, leading to unique conditions of exposure. In most cases, the concentrations of indoor fungi are determined by outdoor concentrations.22

The prevalence of fungi sensitization varies worldwide, depending largely on climatic conditions and the type of fungi under study. According to a survey performed by the Global Allergy and Asthma European Network, the rate of sensitization to intra-domiciliary fungi (A. fumigatus) varied from 0.4% (Italy) to 6.9% (Portugal). The difference in sensitization was even greater for extra-domiciliary fungi, ranging from 0.5% (Finland) to 12.8% (Hungary) for Cladosporium, and from 2% (Finland) to 18.6% (Hungary) for Alternaria.23

In the United States, the Third National Survey of Health and Nutrition revealed that approximately 12.9% of the population under study displayed sensitization to A. alternata.24 Mari et al. reported that 19.1% of the total allergic population at Rome's National Health Service Allergy Unit in Italy had positive skin tests for at least one type of fungus. Of the latter, the sensitization prevalence was 66.1% for Alternaria, 12.6% for Aspergillus, 44.3% for Candida, 13.1% for Cladosporium, and 8.1% for Penicillium.3

The sub-humid climate previously mentioned for Mexico City covers 87% of its surface area, with a median annual temperature of 16°C. In the final year of the current study (2015), the rate of sensitization to at least one fungus was almost 58%, while this parameter was 20.7% when considering at least two types of fungi and 5.8% for at least three types. Hence, a low percentage existed in relation to multiple sensitizations. Regarding sensitization to at least one type of fungus, there is a critical difference between the present finding (57.2%) and that of Mari et al. in Rome (19.1%). The current results are more similar to those reported by Pongracic et al., who found skin tests positive to at least one fungal allergen extract in up to 50% of children with asthma (from 5 to 11 years of age). A notable prevalence was observed for Alternaria (36%), followed by Aspergillus (27%), Cladosporium (18%) and Penicillium (13%). For children over the age of six, a considerable prevalence existed for Alternaria (15.3%), Aspergillus (17%), Cladosporium (6.6%) and Penicillium (13.1%). Additionally, Candida was detected at 17%.6

Moral et al.21 described a distinct behavior for Alternaria compared to other aeroallergens among patients 0–14 years old. Sensitization to this fungus increased abruptly during early infancy (3–5 years of age), reached a peak at seven years of age, and stabilized (or even decreased) in older children. In contrast, the data herein evidences a greater tendency to sensitization between 16 and 18 years of age for Alternaria, Aspergillus, Candida and Cladosporium. For Mucor and Penicillium, on the other hand, the sensitization prevalence was higher in children 10–12 and 12–14 years old, respectively. In a study by Li et al. on patients 5–65 years old with asthma and/or rhinitis, there were elevated levels of sensitization to a combination of fungi for patients 5–14 and 15–24 years old. When stratifying between children and adults, the data was distinct in the four different regions, with 22.1% sensitization for children and 5.3% for adults in the North, 6% for children and 4% for adults in the East, 6.3% for children and 2.7% for adults in the Southeast, and 2.9% for children and 3.4% for adults in the Southeastern coastal area.25 These results were similar to those found presently (Table 4), with greater sensitization levels for children, which later stabilized or even diminished during adolescence and afterwards.

Curiously, the rates of sensitization to fungi detected in follow-up cohort studies are very low, or are not reported at all. According to two cohort studies by Rönmark et al., positive skin tests for fungi were very uncommon for children 7–8 years old. These authors reported a prevalence of Cladosporium at 1.1% and 1.3% in 1996 and 2006, respectively, and that of Alternaria at 0.6% and 0.7% during the same years.26 Broadfield et al. evaluated the prevalence of skin sensitization in a nine-year longitudinal study on a cohort of adults from 18 to 70 years old, observing very few subjects with sensitization to fungi. There was an increase from 1991 to 2000 for A. fumigatus (from 1.4% to 3.2%) and for C. herbarum (from 0.4% to 2.2%).27 In a report on randomized skin tests and structured interviews in two population groups ranging from 20 to 60 years of age, Warm et al. documented in 1994 and 2009 that sensitization to Cladosporium and Alternaria was uncommon. Prevalence for Cladosporium in 1994 was 3% for men and 3.7% for women, while in 2009 it was 1.7% for both groups. Interestingly, the patients with the highest levels of sensitization to both types of fungi were those 20–29 years of age. In 1994 and 2009, this age group showed 8.5% and 5.4% for Cladosporium, and 4.3% and 3.6% for Alternaria, respectively.28 In 2015 (the last year of the 11-year period), we found lower rates of sensitization to Alternaria, Cladosporium, Aspergillus and Mucor, as opposed to higher rates for Penicillium and especially Candida.

A comparison of the present results and similar studies throughout the country revealed variations in the percentage of sensitization, depending on the location being examined, the type of extract used, and the population sample. The following data portray the levels of sensitization to fungi (in decreasing order) that correspond to distinct states in Mexico: Alternaria at 35% in Michoacán, 10.8% in Jalisco, and 5.5% in Nuevo León; Cladosporium at 3.8% in Nuevo León and 0.9% in Jalisco; Aspergillus at 23.2% in Michoacán, 22% in Sonora, 3.3% in Jalisco and 3.2% in Nuevo León; Candida at 18.9% in Michoacán and 16.7% in Jalisco.11–16 In the current investigation, the percentage of sensitization proved to be greater than that documented in the rest of the country. This can be explained in part by the fact that our hospital is a concentration and reference center for other hospitals in the area, and in some cases from other states. On the other hand, the sensitization distribution is more likely determined by climatic conditions, especially variations in temperature and humidity in different regions and years.

Improvements in the diagnosis and treatment of fungal allergies have been hindered by the extreme variability in the protein composition of fungal extracts, which is due to the strain and batch. Additionally, extracts are commonly made from spores and/or mycelial cells.1 Despite the dozens of commercial products currently available, standardized fungal extracts are still unavailable for use as a reference.2 Hence, a strength of the present study was the use of the same type of extract on a relatively similar population over 11 years. A limitation is that data is not available for the levels of humidity from year to year, although the volume of precipitation is known. Regarding the latter parameter, there was little change from 2004 to 2015. The highest value was detected in 2007 (871.4mm accumulated monthly) and the lowest in 2005 (597.2mm accumulated monthly).29

ConclusionThe rate of sensitization to at least one type of fungus in the current population was over 50%, which is greater than that found in other medical centers in Mexico. This elevated rate was constant over the 11-year period of the investigation. The highest level of sensitization corresponded to Aspergillus.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

The authors thank Maria de Lourdes Lerma Ortiz (chemist), Allergy Laboratory, Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez, for excellent collaboration.