Asthma hospitalization rates in Chilean children have increased in the last 14 years, but little is known about the factors associated with this.

ObjectiveDescribe clinical characteristics of children hospitalized for asthma exacerbation.

MethodsObservational prospective cohort study in 14 hospitals. Over a one-year period, children five years of age or older hospitalized with asthma exacerbation were eligible for inclusion. Parents completed an online questionnaire with questions on demographic information, about asthma, indoor environmental contaminant exposure, comorbidities and beliefs about disease and treatment. Disease control was assessed by the Asthma Control Test. Inhalation technique was observed using a checklist.

Results396 patients were enrolled. 168 children did not have an established diagnosis of asthma. Only 188 used at least one controller treatment at the time of hospitalization. 208 parents said they believed their child had asthma only when they had an exacerbation and 97 correctly identified inhaled corticosteroids as anti-inflammatory treatment. 342 patients used the wrong spacer and 73 correctly performed all steps of the checklist.

ConclusionsAlmost half of the patients were not diagnosed with asthma at the time of hospitalization despite having a medical history suggestive of the disease. In the remaining patients with an established diagnosis of asthma potentially modifiable factors like bad adherence to treatment and poor inhalation technique were found. Implementing a nationwide asthma program including continued medical education for the correct diagnosis and follow up of these patients and asthma education for patients and caregivers is needed to reduce asthma hospitalization rates in Chilean children.

Asthma affects more than 300 million people worldwide and is the most frequent chronic disease in children.1 In Chile, according to The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC), the prevalence of asthma is 17.9% in 6–7-year old children and 15.5% in 13–14-year olds.2 Asthma admission rates have been proposed as a target indicator for monitoring progress toward improved asthma care. Large reductions in admissions have already occurred over the last decade in several countries. However, the available information is almost entirely restricted to high-income countries.3 A recent Chilean study showed a significant increase in asthma hospitalizations in 5–15-year-old children, from 3.8 per 10,000 inhabitants in 2001 to 7.8 per 10,000 inhabitants in 2014.4 This increase was mainly seen in the group of 5- to 7-year-olds. Because hospitalizations for asthma in children constitute a considerable burden to children and their families and have a large impact on health care costs, it is important to determine whether there are any factors associated with this increase that may offer opportunities for interventions.5,6 Three earlier Chilean studies reported clinical characteristics of children hospitalized with asthma exacerbations, but these studies were all single-center with a small sample sizes (60–113 patients), limiting their representativeness and generalizability.7–9

The aim of this study was to describe the clinical characteristics of children hospitalized for asthma exacerbation in different centers throughout Chile and to identify potential targets for preventive interventions.

MethodsThis was a prospective cohort study in 14 tertiary care medical centers throughout Chile, eight in the Santiago metropolitan area and six in other regions of the country. Each child five years of age or older who was hospitalized with an asthma exacerbation between August 16, 2015 and August 16, 2016 was eligible for inclusion in the study. We defined asthma exacerbation as an acute episode of progressive increase in shortness of breath, wheezing, chest tightness or a combination of these symptoms that required the use of rescue bronchodilator and systemic corticosteroids.

In each center, members of the research team identified eligible patients in hospital admission records on a daily basis from Monday to Friday. During the first 72h of admission, after obtaining written informed consent from the parents, and from the child if he/she was over 12 years of age, the parents were asked to complete an online questionnaire with questions on demographic information of the child and family, questions about asthma (whether the child had a doctor's diagnosis of asthma or a history of recurrent wheeze, use of controller treatment and who managed this treatment, use of a spacer device, use of oral corticosteroids in the last 12 months, visits to emergency rooms (ER), hospitalizations, frequency of scheduled outpatient visits, and whether or not the attending physician had provided the parents with a written action plan). Parents also provided data about indoor environmental contaminant exposure (heating systems and tobacco smoke exposure) and about the presence of comorbidities such as allergic rhinitis and gastroesophageal reflux (see appendix for the complete questionnaire).

Based on the recorded information on daily controller medication, asthma was classified as mild, moderate or severe.10 Self-reported adherence was recorded on a five-point scale: everyday use; almost every day use; use on some days of the week; once a week; or less than once a week.

Beliefs about disease and treatment were explored using questions like: “Do you believe your child has asthma?”, if so “Do you believe your child has asthma always or only when he has an asthma exacerbation?”, “Are you afraid of using inhaled corticosteroids?” if so, “Why?”.

Disease control was assessed applying the age-appropriate validated Spanish-language version of the Asthma Control Test (ACT).11,12 Before discharge, researchers directly observed the inhalation technique, asking the patient to demonstrate the use of the inhaler, alone or with the parent's help, according to the daily routine at home. The inhalation technique was evaluated using a seven-point checklist.13 Weight, height and body mass index (BMI) were measured and expressed as z-scores. BMI z-score was classified as eutrophic (z-score between ≤1 SD and −2 SD), overweight (z-score >1 SD) and obese (z-score >2 SD).14

All questionnaire responses were collected electronically and were saved to a central database. The study was approved by the ethics committee of each participating center.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were analyzed using Fisher's exact test, using the odds ratio as a measure of association. Continuous variables were analyzed using the Student's t-test or ANOVA, as appropriate, and ordinal variables with the Kruskal–Wallis test. The association between ordinal variables were studied using Spearman's rank correlation coefficient. Data was analyzed with STATA version 14.0.

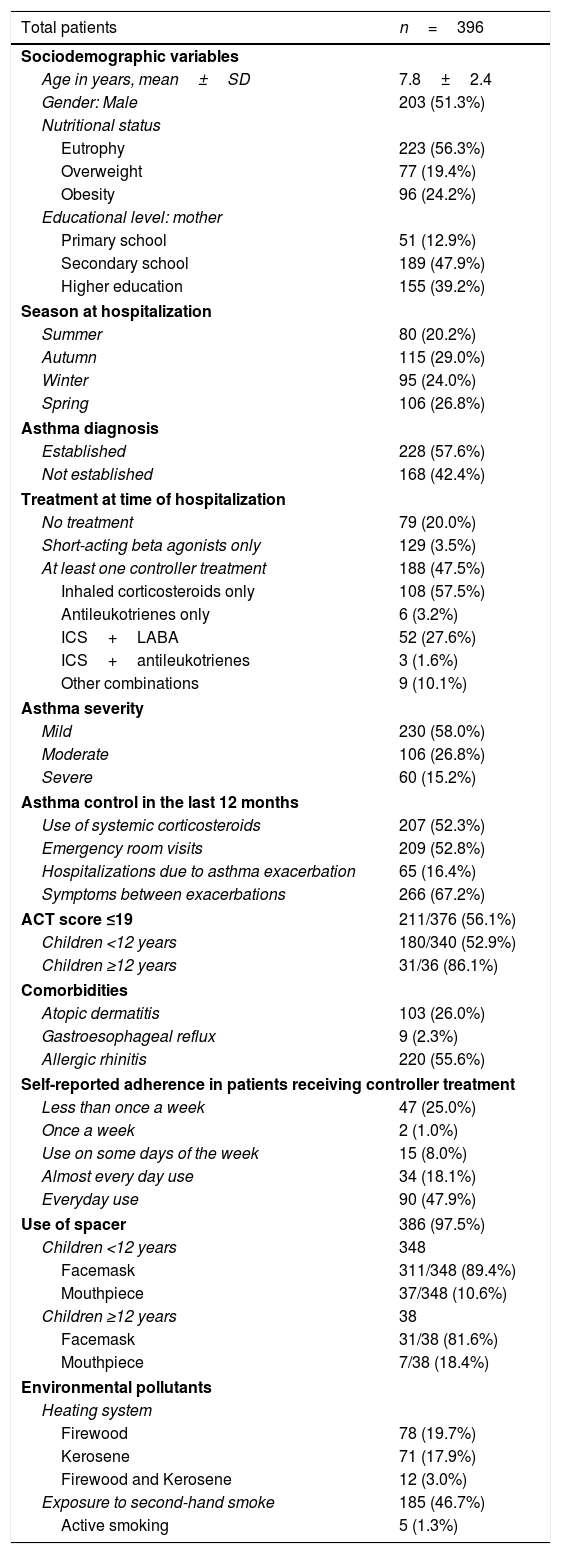

ResultsDuring the study year, 424 children were hospitalized with an asthma exacerbation in the 14 participating hospitals. Twenty-eight patients were not enrolled either due to a lack of parental consent or because they were admitted during the weekend and could not be investigated in time by the research team. The key clinical characteristics of the remaining 396 patients are presented in Table 1. Most patients (90%) were younger than 12 years of age. Almost 60% of patients had an established diagnosis of asthma, which was made at a mean age of 4.3 years (SD 2.3). Asthma was more commonly diagnosed in children older than eight years than in younger children (OR=1.6; 95% CI 1.04–2.45, p=0.03). Most children with no asthma diagnosis had a history of recurrent wheezing (72.6%).

Characteristics of patients hospitalized due to asthma exacerbation.

| Total patients | n=396 |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic variables | |

| Age in years, mean±SD | 7.8±2.4 |

| Gender: Male | 203 (51.3%) |

| Nutritional status | |

| Eutrophy | 223 (56.3%) |

| Overweight | 77 (19.4%) |

| Obesity | 96 (24.2%) |

| Educational level: mother | |

| Primary school | 51 (12.9%) |

| Secondary school | 189 (47.9%) |

| Higher education | 155 (39.2%) |

| Season at hospitalization | |

| Summer | 80 (20.2%) |

| Autumn | 115 (29.0%) |

| Winter | 95 (24.0%) |

| Spring | 106 (26.8%) |

| Asthma diagnosis | |

| Established | 228 (57.6%) |

| Not established | 168 (42.4%) |

| Treatment at time of hospitalization | |

| No treatment | 79 (20.0%) |

| Short-acting beta agonists only | 129 (3.5%) |

| At least one controller treatment | 188 (47.5%) |

| Inhaled corticosteroids only | 108 (57.5%) |

| Antileukotrienes only | 6 (3.2%) |

| ICS+LABA | 52 (27.6%) |

| ICS+antileukotrienes | 3 (1.6%) |

| Other combinations | 9 (10.1%) |

| Asthma severity | |

| Mild | 230 (58.0%) |

| Moderate | 106 (26.8%) |

| Severe | 60 (15.2%) |

| Asthma control in the last 12 months | |

| Use of systemic corticosteroids | 207 (52.3%) |

| Emergency room visits | 209 (52.8%) |

| Hospitalizations due to asthma exacerbation | 65 (16.4%) |

| Symptoms between exacerbations | 266 (67.2%) |

| ACT score ≤19 | 211/376 (56.1%) |

| Children <12 years | 180/340 (52.9%) |

| Children ≥12 years | 31/36 (86.1%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Atopic dermatitis | 103 (26.0%) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 9 (2.3%) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 220 (55.6%) |

| Self-reported adherence in patients receiving controller treatment | |

| Less than once a week | 47 (25.0%) |

| Once a week | 2 (1.0%) |

| Use on some days of the week | 15 (8.0%) |

| Almost every day use | 34 (18.1%) |

| Everyday use | 90 (47.9%) |

| Use of spacer | 386 (97.5%) |

| Children <12 years | 348 |

| Facemask | 311/348 (89.4%) |

| Mouthpiece | 37/348 (10.6%) |

| Children ≥12 years | 38 |

| Facemask | 31/38 (81.6%) |

| Mouthpiece | 7/38 (18.4%) |

| Environmental pollutants | |

| Heating system | |

| Firewood | 78 (19.7%) |

| Kerosene | 71 (17.9%) |

| Firewood and Kerosene | 12 (3.0%) |

| Exposure to second-hand smoke | 185 (46.7%) |

| Active smoking | 5 (1.3%) |

At the time of hospitalization less than half of the patients used at least one controller treatment (Table 1). Based on the treatment received by patients at the time of hospitalization, most children had mild asthma (Table 1).

Asthma controlMost children had poorly-controlled asthma, with frequent use of systemic corticosteroids, ER visits, symptoms between exacerbations, and low ACT scores (Table 1). Low ACT score was observed more frequently in children older than 12 years old in comparison with children younger than 12 (86.1% vs. 52.9%, p<0.0001). Children who had been hospitalized earlier were significantly younger (mean seven years, SD 2.1) than those who were not (mean eight years, SD 2.5) (p=0.004). Earlier hospitalizations were directly associated with the use of oral corticosteroids (OR=12.2, 95% CI 5.1 28.9, p<0.001).

ComorbiditiesAlthough rhinitis was a frequent comorbidity, only 60.5% of patients with this diagnosis were receiving treatment.

Adherence and inhalation techniqueIn 49/188 patients (26.0%) having been prescribed controller therapy, self-reported adherence was poor (Table 1). A positive correlation was found between asthma severity and self-reported adherence. This association was statistically significant but weak (Spearman rho=0.22, p=0.0029). At the time of hospitalization, 94 patients (27.4%) had discontinued maintenance therapy, with a median of 30 days prior to admission. When observing the inhalation technique, only 73 patients (18.4%) correctly performed all seven steps of the checklist, although 355 parents (89.7%) reported having been taught, at least on one occasion, the correct use of the inhaler and spacer. Most children used a spacer with facemask instead of a mouthpiece despite being school age children (Table 1).

Parental beliefs regarding disease and treatmentWhen parents were asked about the chronicity of their child's disease, 208 (52.5%) said they believed their child had asthma only when they had an exacerbation, and 63 (15.9%) did not believe their child had asthma at all. 128 parents (32.3%) reported fear of using permanent inhaled corticosteroid treatment; in 32 of them (25%) because they believed their child would become dependent on using an inhaler and in 96 (75%) because they feared other possible adverse effects. When parents were asked to describe salbutamol, 286 (72.2%) correctly answered that it is a bronchodilator. In contrast, only 97 parents (24.5%) recognized inhaled corticosteroids as anti-inflammatory treatment. According to 332 parents (83.8%), salbutamol should be used intermittently; 34 (8.6%) responded that it should be used daily. A total of 192 parents (48.5%) reported daily use of inhaled corticosteroids while 79 (20%) used the medication intermittently.

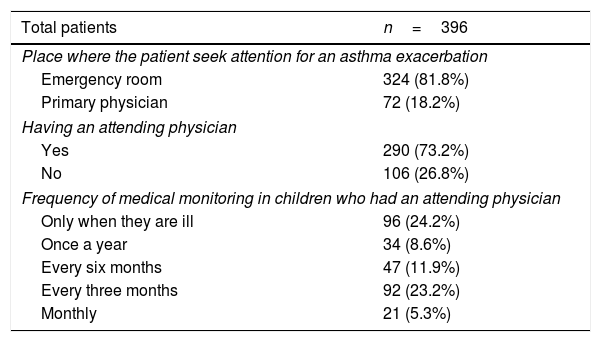

Medical monitoring and action planWhen an asthma exacerbation occurred, most patients went to the ER (Table 2). Almost one-third of patients did not have an attending physician, seeking only medical attention at the ER when the child had an asthma exacerbation. Many patients with an attending physician were seen only when ill (Table 2). There was a positive correlation between asthma severity and the frequency of medical monitoring. This association was statistically significant but weak (Spearman rho=0.28, p=0.001).

Medical attention and monitoring.

| Total patients | n=396 |

|---|---|

| Place where the patient seek attention for an asthma exacerbation | |

| Emergency room | 324 (81.8%) |

| Primary physician | 72 (18.2%) |

| Having an attending physician | |

| Yes | 290 (73.2%) |

| No | 106 (26.8%) |

| Frequency of medical monitoring in children who had an attending physician | |

| Only when they are ill | 96 (24.2%) |

| Once a year | 34 (8.6%) |

| Every six months | 47 (11.9%) |

| Every three months | 92 (23.2%) |

| Monthly | 21 (5.3%) |

This study highlighted considerable shortcomings in the diagnosis and management of asthma in 5–15-year-old Chilean children which likely contributed to the risk of hospitalization. Almost half of the patients were not diagnosed with asthma at the time of hospitalization despite having a medical history very suggestive of the disease. This may explain why many patients only used the ER system for their asthma care. It seems that primary care physicians are reluctant to make an asthma diagnosis, delaying the start of treatment. For that reason, it is important to carry out continued medical education for pediatricians, primary-care physicians and ER doctors, for an adequate diagnostic suspicion, diagnostic work-out, and timely referral and treatment of these patients.

The majority of our patients had poor control of the disease, reflected in a low ACT, use of oral corticosteroids, previous hospitalizations and a high prevalence of daily symptoms. Our data did not allow us to reliably distinguish between those with difficult-to-treat asthma with potentially modifiable factors and those with therapy-resistant asthma.15 However, the former is more likely than the latter, for a number of reasons. First, difficult-to-treat asthma is much more common than therapy-resistant asthma: previous studies showed modifiable factors in 79–97% of children with difficult-to-control asthma.16,17 Second, about one-third of patients with allergic rhinitis had no treatment for it, and this has been associated with poor asthma control in earlier studies.18,19 Third, about 50% of patients were exposed to second-hand smoke, which is associated with an increased risk of asthma exacerbations.20 Fourth, significant shortcomings in inhalation technique were found in more than 80% of the patients, which has also been associated with poor asthma control.16 Poor adherence to daily controller therapy is likely to be the main cause of poor disease control.21–23 In the present study, more than a third of patients who had been prescribed daily controller therapy reported poor adherence. This is likely to be an underestimate of the true non-adherence rate given the unreliability of parent-reported adherence.24 Furthermore, about one-third of hospitalized patients had suspended maintenance treatment prior to hospitalization. Poor adherence to treatment is strongly related to the parents’ illness and medication beliefs.25 In this study, we observed parents’ misconceptions about asthma, regarding issues such as the chronicity of the disease, the goal of treatment, and the role and working mechanisms of the different inhaled medications.

The results of this study highlight the need for improvement asthma education activities for all patients and their parents in Chile to improve treatment adherence and asthma control. Such programs have been successfully applied, not only in western countries but also in developing nations in Latin America.26 For example, a program implemented in Belo Horizonte, Brazil achieved a reduction of 79% in asthma hospitalizations.27

Education in asthma is fundamental. To be effective, education must be personalized and tailored to the patient, not only based on information, but also trying to achieve a behavioral change that leads to a better adherence to therapy.25 It is also important to consider the family's environment, parents’ perception about asthma and their beliefs and preferences with regard to treatment, including them in a shared decision process.28 In this study many asthmatic patients were not monitored on a regular basis and most did not have a written action plan as recommended by asthma guidelines.10 Such an individualized written action plan is important because it helps patients to start asthma exacerbation treatment at home, which helps to reduce acute care visits.29

The main strengths of this study are its nationwide multicenter design, and the detailed characterization of a large group of children with asthma requiring hospitalization for acute exacerbations. The study highlights several opportunities for the improvement of asthma education and chronic asthma care, the limitations of this study include the lack of data on atopy and lung function, the lack of more objective adherence measurements, and the lack of a control group of asthmatic children not requiring hospitalization for acute exacerbations. The cross-sectional analysis precludes causal inference.

In conclusion, potentially modifiable factors in the management of asthma were found in the majority of children hospitalized for asthma exacerbation in Chile. Implementing a systematic, preferable nationwide asthma program including continued medical education for the correct diagnosis and follow up of these patients and asthma education for patients and caregivers is needed to reduce asthma hospitalization rates in children in Chile.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.