Atopic eczema (AE) is the most frequent inflammatory skin disease in childhood in the western world. Several studies have reported a significant increase of prevalence in recent decades and the environmental factors implicated in its aetiology, including environmental tobacco smoke.

This study aims to investigate the possible association of AE prevalence in Spanish schoolchildren aged 6-7 and 13-14 years in relation to their parents’ smoking habits.

MethodsWe conducted a cross-sectional population-based study with 6-7 year-old (n=27805) and 13-14 year-old (n=31235) schoolchildren from 10 Spanish centres. AE prevalence was assessed using the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) questionnaire, and the Spanish Academy of Dermatology criteria, used in Spain to diagnose AE.

ResultsAn association was found in schoolchildren aged 6-7 (adjusted for gender, presence of asthma, presence of rhinitis, siblings and mother's level of education) between AE being clinically diagnosed with the mother's smoking habit (RPRa 1.40, 1.10-1.78) and there being more than 2 smokers at home (RPRa 1.34, 1.01-1.78). Regarding the presence of itchy rash, an association was observed with fathers who smoke (RPRa 1.40, 1.13-1.72). Among the 13-14 year-olds, no association was observed in relation to either clinically diagnosed AE or the appearance of itchy rash with parents’ smoking habit.

ConclusionsOur results indicate the risk for children of being exposed to environmental tobacco smoke in terms of AE, especially when they are younger.

Atopic eczema (AE) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterised by itching, lesions and lichenification, especially at the flexure sites of the major joints of upper and lower extremities1. It primarily starts in infancy and childhood2 and is the most frequent inflammatory skin disease at these ages3.

Several studies have reported a significant increase of AE prevalence in recent decades4–6. Certain aetiopathogenic aspects7,8 and the mechanism behind this increase9 remain unclear, and are presumed to be multi-factorial. This prevalence has been connected to family-related factors10–14, but because genetic factors alone cannot sufficiently explain this trend, environmental factors have been discussed as possible contributors in its aetiology3,8,15–18.

The emergence of new environmental risk factors, and/or the loss of traditional lifestyle protective factors may explain the increase or variations in the prevalence of allergic diseases19. This is especially relevant in children because the period immediately after birth is a sensitive period for the development of atopic disease2, and the impact of environmental exposures on the development of atopic disorders appears to be most important during the first year of life14,20,21.

A long list of suggested modulating environmental and/or lifestyle factors reported to be important in allergies include environmental tobacco smoke or passive smoking6. Environmental tobacco smoke has been postulated as a risk factor of allergies19, and is one of the most common indoor air pollutants22. The home is the most important site of such exposure22–24 and children are more likely than adults to suffer from environmental tobacco smoke in relation to health effects. This negative impact of environmental airway diseases in children is well known. However, their effect on AE remains unclear22, and the effect of smoking on AE has reported controversial knowledge19,25,26. Despite a number of negative findings (reviewed by Strachan and Cook)27,28, some studies identified a positive effect of environmental tobacco smoke on AE2,22.

The aim of this study is to investigate the possible association of AE prevalence in schoolchildren aged 6-7 and 13-14years in Spain in relation to their parents’ smoking habits.

MATERIALS AND METHODSOverviewThis was a case-control nested cross-sectional population-based study (n = 59040), which used the ISAAC methodology, designed to investigate the role of parents’ smoking habits in relation to AE prevalence in Spanish schoolchildren aged 6-7 and 13-14years.

Study PopulationThe population groups included schoolchildren aged 6-7 and 13-14years, and the sample size was 59040. The ISAAC questionnaire was answered by the 31235 schoolchildren aged 13-14 and by the parents of the 27805 schoolchildren aged 6-7. The Spanish schools participating were from Asturias, Barcelona, Bilbao, Cartagena (coordinating centre), Castellón, A Coruña, Madrid, Pamplona, San Sebastián and Valencia.

Sample collectionA survey was conducted using the standardised and validated questionnaire of the Phase III ISAAC study. It included questions on AE and the parents’ smoking habits29,30.

The questionnaire was used to assess AE prevalence and the parents’ smoking habits, with the following questions: 1) Has your child/have you ever had an itchy rash which has been coming and going for at least 6months? (yes/no); 2) Has this itchy rash at any time affected any of the following places: the folds of the elbows, behind the knees, the front of the ankles, under the buttocks, and around the neck, ears, or eyes? (yes/no); 3) Has your child/have you ever been clinically diagnosed with eczema or atopic dermatitis by a specialist? (yes/no); 4) Does your (child's) mother smoke cigarettes? (yes/no); 5) About how many cigarettes does your (child's) mother smoke each day?; 6) Does your (child's) father smoke cigarettes? (yes/no); 7) About how many cigarettes does your (child's) father smoke each day?; 8) Did your (child's) mother smoke cigarettes during the child's first year of life? (yes/no); 9) How many smokers live in your (child's) home, including parents. The 13-14year-olds did not answer Questions 5, 7, 8 and 9 since they could not accurately answer these questions (parents of the 6-7year-olds answered these questions).

AE assessmentAccording to the ISAAC criteria questions31, affirmative responses to Questions 1 and 2 were defined as presenting AE symptoms (itchy rashes). The schoolchildren of parents who answered affirmatively to Question 3 were defined as being diagnosed with AE by a medical specialist. In Spain, a diagnosis is usually made according to the Spanish Academy of Dermatology (SAD) criteria based on the diagnostic criteria scale developed by Hanifin and Rajka in 198032.

Statistical analysisPrevalences were estimated as the percentages of participating schoolchildren. The relevant variables of the parents’ smoking habits are presented as percentages. Comparisons were made with the chi-square test (confidence interval, 95 %).

The association between parents’ smoking habits and AE in children was expressed as the Crude Relative Prevalent Ratio (RPRc). The factors examined as potential confounding influences were those that may be modified by the influence of the smoking habit on AE. Relevant factors were included in the multiple regression modelling to calculate the Adjusted Relative Prevalent Ratio (RPRa) (gender, presence of asthma, presence of rhinitis, siblings and mother's level of education). We also applied 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI). All the statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software (version 15).

Ethical approvalThe regional ethics committee of Asturias approved this study for all ISAAC III centres in Spain.

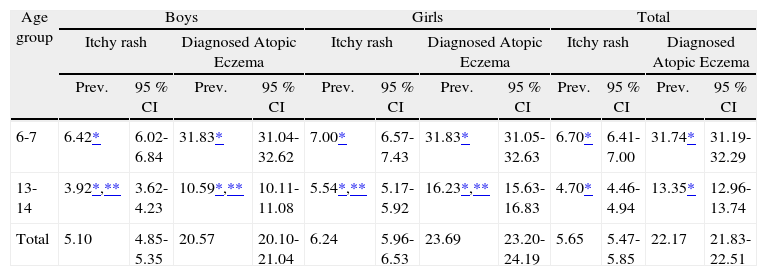

RESULTSPrevalenceTable I shows the prevalence of rashes and diagnosed AE according to gender in 6-7 and 13-14year-old schoolchildren. We observed a higher prevalence of rashes in the 6-7 (6.70 %) year-olds than in the 13-14year-olds (4.70 %) (p < 0.001). Interestingly, the same occurred with AE where there was a higher prevalence (31.74 % vs. 13.35 %, respectively) (p < 0.001). Both conditions are more frequent in girls than in boys of both age groups studied with only statistically significant differences in the 13-14 (p < 0.001) year-old group. We also noted how the prevalence of both conditions which lowered with age was more pronounced in boys than girls.

Prevalence and Confidence Intervals (95 %) of itchy rash and diagnosed AE by gender in 6-7 and 13-14year-old schoolchildren

| Age group | Boys | Girls | Total | |||||||||

| Itchy rash | Diagnosed Atopic Eczema | Itchy rash | Diagnosed Atopic Eczema | Itchy rash | Diagnosed Atopic Eczema | |||||||

| Prev. | 95 % CI | Prev. | 95 % CI | Prev. | 95 % CI | Prev. | 95 % CI | Prev. | 95 % CI | Prev. | 95 % CI | |

| 6-7 | 6.42* | 6.02-6.84 | 31.83* | 31.04-32.62 | 7.00* | 6.57-7.43 | 31.83* | 31.05-32.63 | 6.70* | 6.41-7.00 | 31.74* | 31.19-32.29 |

| 13-14 | 3.92*,** | 3.62-4.23 | 10.59*,** | 10.11-11.08 | 5.54*,** | 5.17-5.92 | 16.23*,** | 15.63-16.83 | 4.70* | 4.46-4.94 | 13.35* | 12.96-13.74 |

| Total | 5.10 | 4.85-5.35 | 20.57 | 20.10-21.04 | 6.24 | 5.96-6.53 | 23.69 | 23.20-24.19 | 5.65 | 5.47-5.85 | 22.17 | 21.83-22.51 |

Prev.: Prevalence (%); 95 % CI: 95 % Confidence Interval.

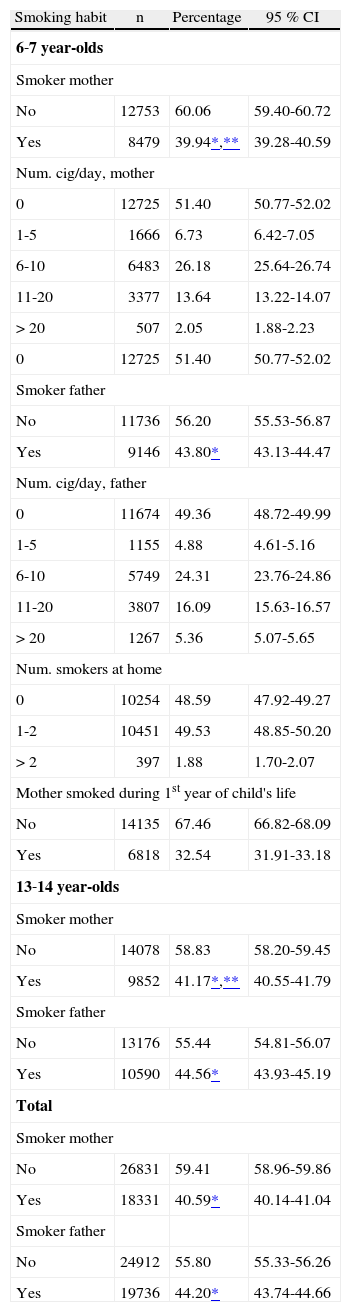

Table II shows the parents’ smoking habits; 40.59 % of mothers and 44.20 % of fathers reported smoking. We observed that fathers smoked more than mothers, and statistically significant differences in both the age groups studied were found (p < 0.001). The percentage of smokers was higher in mothers and fathers of the 13-14year-old age group than in the parents of the younger schoolchildren, but statistically significant differences were only noted for mothers (p < 0.05).

Parents’ smoking habits

| Smoking habit | n | Percentage | 95 % CI |

| 6-7year-olds | |||

| Smoker mother | |||

| No | 12753 | 60.06 | 59.40-60.72 |

| Yes | 8479 | 39.94*,** | 39.28-40.59 |

| Num. cig/day, mother | |||

| 0 | 12725 | 51.40 | 50.77-52.02 |

| 1-5 | 1666 | 6.73 | 6.42-7.05 |

| 6-10 | 6483 | 26.18 | 25.64-26.74 |

| 11-20 | 3377 | 13.64 | 13.22-14.07 |

| > 20 | 507 | 2.05 | 1.88-2.23 |

| 0 | 12725 | 51.40 | 50.77-52.02 |

| Smoker father | |||

| No | 11736 | 56.20 | 55.53-56.87 |

| Yes | 9146 | 43.80* | 43.13-44.47 |

| Num. cig/day, father | |||

| 0 | 11674 | 49.36 | 48.72-49.99 |

| 1-5 | 1155 | 4.88 | 4.61-5.16 |

| 6-10 | 5749 | 24.31 | 23.76-24.86 |

| 11-20 | 3807 | 16.09 | 15.63-16.57 |

| > 20 | 1267 | 5.36 | 5.07-5.65 |

| Num. smokers at home | |||

| 0 | 10254 | 48.59 | 47.92-49.27 |

| 1-2 | 10451 | 49.53 | 48.85-50.20 |

| >2 | 397 | 1.88 | 1.70-2.07 |

| Mother smoked during 1st year of child's life | |||

| No | 14135 | 67.46 | 66.82-68.09 |

| Yes | 6818 | 32.54 | 31.91-33.18 |

| 13-14year-olds | |||

| Smoker mother | |||

| No | 14078 | 58.83 | 58.20-59.45 |

| Yes | 9852 | 41.17*,** | 40.55-41.79 |

| Smoker father | |||

| No | 13176 | 55.44 | 54.81-56.07 |

| Yes | 10590 | 44.56* | 43.93-45.19 |

| Total | |||

| Smoker mother | |||

| No | 26831 | 59.41 | 58.96-59.86 |

| Yes | 18331 | 40.59* | 40.14-41.04 |

| Smoker father | |||

| No | 24912 | 55.80 | 55.33-56.26 |

| Yes | 19736 | 44.20* | 43.74-44.66 |

Percentage (%); 95 % CI: 95 % Confidence Interval.

The remaining relative variables of the mothers’ smoking habits were collected for the 6-7year-olds since it was the parents who completed the questionnaire. However in the 13-14 age group, it was the schoolchildren themselves who answered the questionnaire, and we therefore eliminated the questions that we thought they would not be able to answer correctly. The vast majority of the parents of 6-7year-olds who smoked did so and smoked 6/10 cigarettes/day. Only 1.88 % of these parents reported that there were more than 2 smokers in the homes of the 6-7year-olds. Moreover, 32.54 % of the mothers of the schoolchildren of this age smoked during the first year of their child's life.

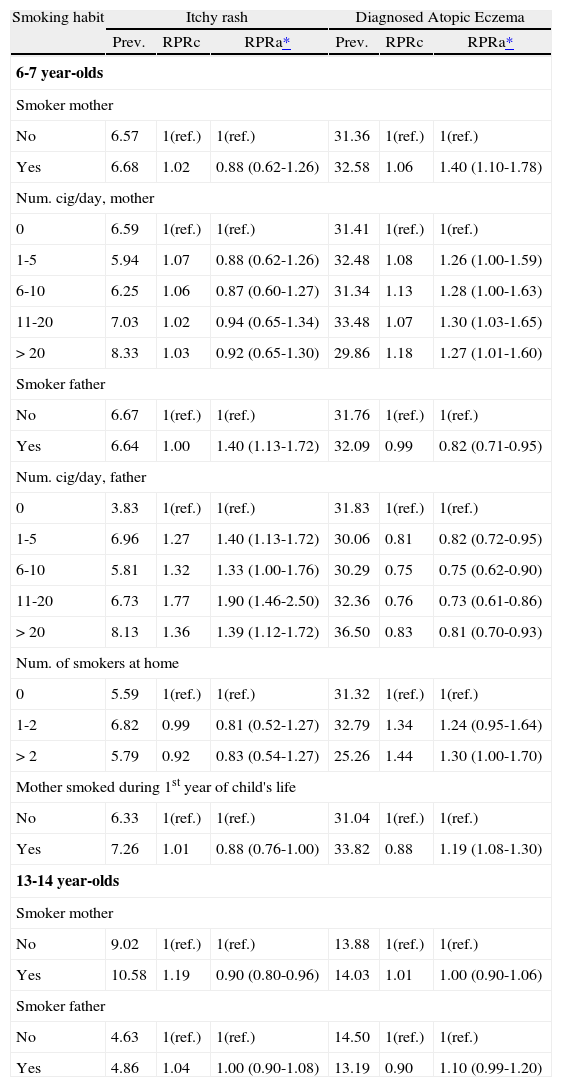

The effects of exposure of environmental tobacco smoke on childrenTable III shows the prevalence of itchy rash and diagnosed AE in relation to the parents’ smoking habits. Among the 6-7year-olds, we note that the presence of clinically diagnosed AE is associated with the mother's smoking habit at the time the study was conducted (RPRa 1.40, 1.10-1.78), during the first year of the child's life (RPRa 1.19, 1.08-1.30), and if the child lived with more than 2 smokers (RPRa 1.34, 1.01-1.78). Conversely, we observed that the presence of itchy rash was associated with the father's smoking habit (RPRa 1.40, 1.13-1.72) (RPR adjusted for gender, presence of asthma, presence or rhinitis, siblings and mother's level of education).

Prevalence and Relative Prevalent Ratio of itchy rash and diagnosed AE according to parental smoking

| Smoking habit | Itchy rash | Diagnosed Atopic Eczema | ||||

| Prev. | RPRc | RPRa* | Prev. | RPRc | RPRa* | |

| 6-7year-olds | ||||||

| Smoker mother | ||||||

| No | 6.57 | 1(ref.) | 1(ref.) | 31.36 | 1(ref.) | 1(ref.) |

| Yes | 6.68 | 1.02 | 0.88 (0.62-1.26) | 32.58 | 1.06 | 1.40 (1.10-1.78) |

| Num. cig/day, mother | ||||||

| 0 | 6.59 | 1(ref.) | 1(ref.) | 31.41 | 1(ref.) | 1(ref.) |

| 1-5 | 5.94 | 1.07 | 0.88 (0.62-1.26) | 32.48 | 1.08 | 1.26 (1.00-1.59) |

| 6-10 | 6.25 | 1.06 | 0.87 (0.60-1.27) | 31.34 | 1.13 | 1.28 (1.00-1.63) |

| 11-20 | 7.03 | 1.02 | 0.94 (0.65-1.34) | 33.48 | 1.07 | 1.30 (1.03-1.65) |

| > 20 | 8.33 | 1.03 | 0.92 (0.65-1.30) | 29.86 | 1.18 | 1.27 (1.01-1.60) |

| Smoker father | ||||||

| No | 6.67 | 1(ref.) | 1(ref.) | 31.76 | 1(ref.) | 1(ref.) |

| Yes | 6.64 | 1.00 | 1.40 (1.13-1.72) | 32.09 | 0.99 | 0.82 (0.71-0.95) |

| Num. cig/day, father | ||||||

| 0 | 3.83 | 1(ref.) | 1(ref.) | 31.83 | 1(ref.) | 1(ref.) |

| 1-5 | 6.96 | 1.27 | 1.40 (1.13-1.72) | 30.06 | 0.81 | 0.82 (0.72-0.95) |

| 6-10 | 5.81 | 1.32 | 1.33 (1.00-1.76) | 30.29 | 0.75 | 0.75 (0.62-0.90) |

| 11-20 | 6.73 | 1.77 | 1.90 (1.46-2.50) | 32.36 | 0.76 | 0.73 (0.61-0.86) |

| > 20 | 8.13 | 1.36 | 1.39 (1.12-1.72) | 36.50 | 0.83 | 0.81 (0.70-0.93) |

| Num. of smokers at home | ||||||

| 0 | 5.59 | 1(ref.) | 1(ref.) | 31.32 | 1(ref.) | 1(ref.) |

| 1-2 | 6.82 | 0.99 | 0.81 (0.52-1.27) | 32.79 | 1.34 | 1.24 (0.95-1.64) |

| >2 | 5.79 | 0.92 | 0.83 (0.54-1.27) | 25.26 | 1.44 | 1.30 (1.00-1.70) |

| Mother smoked during 1st year of child's life | ||||||

| No | 6.33 | 1(ref.) | 1(ref.) | 31.04 | 1(ref.) | 1(ref.) |

| Yes | 7.26 | 1.01 | 0.88 (0.76-1.00) | 33.82 | 0.88 | 1.19 (1.08-1.30) |

| 13-14year-olds | ||||||

| Smoker mother | ||||||

| No | 9.02 | 1(ref.) | 1(ref.) | 13.88 | 1(ref.) | 1(ref.) |

| Yes | 10.58 | 1.19 | 0.90 (0.80-0.96) | 14.03 | 1.01 | 1.00 (0.90-1.06) |

| Smoker father | ||||||

| No | 4.63 | 1(ref.) | 1(ref.) | 14.50 | 1(ref.) | 1(ref.) |

| Yes | 4.86 | 1.04 | 1.00 (0.90-1.08) | 13.19 | 0.90 | 1.10 (0.99-1.20) |

Prev.: Prevalence; RPRc: Relative Prevalent Ratio, Crude; RPRa: Relative Prevalent Ratio, Adjusted.

No association with any of the studied variables was noted for the 13-14year-old group.

DISCUSSIONFrom the results of the present study we may clearly observe (in the 6-7year-old age group) that the presence of clinically diagnosed AE was associated with the mother's smoking habit when the study was conducted, during the first year of the child's life, and when there were more than 2 smokers living at the child's home. All this underlines the importance of children of these ages being exposed to environmental tobacco smoke in relation to the presence of AE.

These results concur with the results found in other studies carried out with schoolchildren of the same ages. Schafer et al. and Coswell et al. reported a significant association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and/or lactation and AE in 5-6year-olds. They showed that those children whose mothers had smoked during pregnancy/lactation presented more manifestations of atopy than children born of non-smoking mothers33,34. Zeiger and Heller also performed a study on 7-year-old schoolchildren and they detected that parental smoking influenced both the presence and extent of atopy in children6. Nonetheless, much controversy on this matter exists in the literature. Although these publications support our findings, other works did not find an association between the parents’ smoking habits and environmental tobacco smoke exposure and the development of atopy in schoolchildren of similar ages. For example, Kramer et al22 found that the prevalence of skin manifestations in children was positively although not significantly associated with environmental tobacco smoke exposure, and they concluded that environmental tobacco smoke could have only an adjuvant effect on AE in children with a genetic disposition to allergies. Luoma detected no significant correlation in general between the development of atopic disease in children aged 5years and their parents’ smoking habits35. There are even studies in which parents’ smoking habits have a protective effect on the development of AE in children. For instance, Kerkhof et al. showed a trend towards a protective effect of smoking on eczema in one-year old children (one explanation could be the lack of control for family hereditary factors in the study)2. Jaakkola et al. also found a significantly lower risk of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke at home for atopic children compared with unaffected children (children aged 1-6years)36. In the present study, the smoking habit of the father is a protective factor for AE. We do not have a clear explanation for this discrepancy between father and mother.

In relation to itchy rash appearing among 6-7 yearolds, we note that the father's smoking habit is associated with them appearing. Both the mother's smoking habit and the number of smokers at the child's home are presented as non-related factors to the presence of this rash. Future studies into this matter will be needed. However, we must bear in mind that the “itchy rash” concept that this work contemplates includes various dermatological pathologies, and not just AE. Indeed, this fact could account for the differences in the results concerning AE and itchy rash.

For the 13-14year-olds, no association was observed between the presence of clinically diagnosed AE and the appearance of red blotches with any of the factors studied. Neither the smoking habits of both parents nor the number of smokers at the child's home was associated with the presence of these conditions for this age group. In that sense, many studies have been done with older children than those already mentioned and whose results indicate the same trend. For example, Schafer et al. conducted a study with children aged 5-14years and found no association between the mother's smoking habit (neither at the time the study was done nor during the child's first year of life) and the development of AE in children3. Similarly, Austin and Rusell also determined that the smoking habit of both parents did not relate with the presence of AE in children aged 1437. There are even some studies, like that of Soyseth et al. in children aged 7-13years, which found that not even the mother's smoking habit during pregnancy was associated with the presence of AE in these older children25.

However, we must bear in mind two aspects when observing the results in the older age group: firstly, 13-14year-olds do not spend so much time with their parents or at home as their younger counterparts do. Therefore it is logical to believe that exposure to environmental tobacco smoke at home is not as influential. Secondly, we wish to point out that our study does not include the older schoolchildren's active smoking habits, and it is reasonable to believe that children of this age may have started smoking themselves38. This fact should be taken into account and, in future studies, it would be interesting to have information about the 13-14year-old's own smoking habits available in order to assess whether their smoking habits relate to AE.

Since some controversy exists in the results of the present study, we need to interpret them cautiously, and not only for the 13-14year-olds. Other peculiarities which may affect the study in general must also be taken into account. We cannot exclude potential factors confounded by family history, which may be associated with smoking habits, as in other studies2. The knowledge of the child's illness could affect the parent's smoking habits36, and the possible association found may have been masked by the fact that the at-risk families had changed their smoking habits following recent health education and prevention programmes3. We have not included the family history of atopy as this question was not incorporated in the ISAAC questionnaire.

Furthermore, studies of biomarkers in urine and hair of Scandinavian Children indicate that those children living in homes without smokers are also exposed to some environmental tobacco smoke and are therefore not a truly unexposed group. This could have contributed to an underestimation of the health effect of passive smoking22.

Because of these controversial results, parents should be advised to avoid smoking in the child's presence because smoking might play a role in the development of AE34. Although genetic factors remain unchangeable, environmental ones, such as environmental smoke exposure, are potentially changeable and deserve modification in an attempt to halt the damage caused by atopic diseases6.

In the light of our results, we may conclude that the effect of smoking on AE should be more deeply investigated by paying special attention to the identification of strategies (interventions) to promote allergy prevention in children. This must include teaching parents about the harmful effects that exposure to tobacco has on their children.

We wish to thank the Spanish Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs, the Carlos III Institute of Health, the Network of Centres (RCESP), the Oscar Rava Foundation 2001, Barcelona, the Department of Health of the Regional Government of Navarre, the International Luis Vives Rotary Foundation 2002-2003, Valencia, the Department of Health of the Regional Government of Murcia, and Astra Zeneca, Spain. We especially thank all the parents who kindly participated and gave us some of their time. Finally, we thank the native translator who checked this article.