The prevalence of asthma in the Brazilian Amazon region is unknown. We studied the prevalence of asthma and associated factors in adolescents (13–14 years old) living in Belem, a large urban centre in this region.

Methods3725 adolescents were evaluated according to the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) protocol and a random sample of them (126 asthmatics and 254 non-asthmatics) were assessed for possible risk factors by a supplementary questionnaire (ISAAC Phase II) and skin prick tests with aeroallergens. The association between asthma and associated factors was determined by logistic regression analysis.

Results3708 adolescents were enrolled, 48% were male. The prevalence of asthma in the last 12 months (identified as asthmatics) and the medical diagnosis of asthma were 20.7% and 29.3%, respectively. Risk factors significantly associated with asthma were: previous diagnosis of tuberculosis (odds ratio [OR]=38.9; 95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 4.6–328.0) and measles (OR=4.7; 95% CI: 2.3–9.8), breastfeeding for any length of time (OR=4.2; 95% CI: 1.1–15.2), current rhinitis (OR=3.2; 95% CI: 1.8–5.9), exposure to smokers (OR=2.4; 95% CI: 1.2–4.5), moisture in home (OR=1.8; 95% CI: 1.1–3.2) and rhinitis diagnosed by physician (OR=1.7; 95% CI: 1.2–2.9). Sensitisation to at least one aeroallergen was significantly higher among asthmatic adolescents (86.5% vs. 32.4%; p<0.0001).

ConclusionsThe prevalence of asthma was similar to that observed in other Brazilian centres. Physician-diagnosed asthma was more frequent than the presence of symptoms suggestive of asthma. Infectious diseases, nutritional and environmental factors, as well as concomitant allergic rhinitis, were the main risk factors associated with the development of asthma in these adolescents.

Respiratory allergies such as asthma and allergic rhinitis are highly prevalent diseases worldwide in both developed and emerging countries. In recent decades, studies have confirmed an overall increase in their prevalence, although on a smaller scale than previously thought, showing a greater increase in the poorest countries, mainly from Africa, Latin America and parts of Asia.1,2

This fact suggests that genetic predisposition alone is not the only indicator of susceptibility to these diseases, and that the gene–environment interaction probably plays a greater role. Therefore, environmental; nutritional; infectious diseases; and psychological factors can act as risk or protection factors in a genetically predisposed individual, depending mainly on the time of exposure (prenatal, perinatal or postnatal).3,4

The first data on the prevalence of allergic diseases in Latin America emerged with the International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Childhood (ISAAC) Phase I and showed high prevalence levels, similar to those in developed countries.5 However, only at the end of ISAAC Phase III in Latin America was there confirmation of the upward trend in asthma prevalence between these two moments of analysis (average of +0.32% per year), with a very large annual average variability between some of the centres involved (−1.06% per year in Peru to +0.88% per year in Panama).1

In Brazil, 58,144 adolescents, aged from 13 to 14 years, were enrolled in ISAAC Phase III. For this age group the mean prevalence rates were: 19.0% for active asthma, 4.7% for severe asthma, and 13.6% for physician-diagnosed asthma.6 There was an inverse relationship between the prevalence of asthma and latitude, with high rates in the north and northeast regions.6

The Amazon region has a peculiar climate. It is crossed in its entirety by the Equator and has high temperature and humidity which can both directly influence the incidence and severity of allergic diseases, mainly respiratory ones.7 Epidemiological data about asthma and allergic diseases are scarce in this region. Prestes et al. applied the ISAAC protocol in adolescents living in Belem, and observed a prevalence rate of 22.1% for physician-diagnosed asthma and 26.4% for current asthma (wheezing in the last year).8

The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of asthma and identify associated factors for the development of asthma in adolescents (13–14 years old) living in the city of Belem, the second largest city in the Amazon region, with 1,393,399 inhabitants and a high miscegenation pattern, particularly with native Indians (65%), living in urban areas, but with a poverty level around 40.6%.9,10

MethodsBetween August 2008 and December 2009, 3725 adolescents (13–14 years old) living in Belem (capital of the state of Para; Amazon region) were enrolled in this cross-sectional study using the ISAAC asthma core written questionnaire (WQ, Phase I), previously validated to the Brazilian culture.11 Data from schoolchildren who participated in the study were provided by the State of Para and City of Belem Education Secretaries official records, and were randomised by convenience sampling. All adolescents answered the ISAAC asthma core WQ by themselves after being authorised by their parents or legal guardians (signed informed consent). The data obtained were transcribed to a database (Microsoft Office Excel® 2007 Inc.). The frequency of affirmative answers to each question was analysed according to gender.

In addition to the WQ, a supplementary questionnaire (CQ; ISAAC Phase II) was applied to a subgroup of the subjects and contained 33 questions including: subject demographics, environmental exposure to infectious agents, allergens, and dietary habits, to be completed by the individual's parents or legal guardians.12 The individuals were classified as asthmatics (wheezing in the last year) and non-asthmatics (no wheezing ever and in the last year) and to calculate each subgroup we used the software SPSS® version 10. For a case-control study, we selected two controls for each case, assuming that the prevalence for each risk factor related to asthma was 20% in the control group, with odds ratio (OR) of 1.5, alpha error of 5% and test power of 85%. Thus, the necessary sample size was defined as 120 cases (asthmatics) and 240 controls (non-asthmatics). The subjects would undergo skin prick test (SPT) using a standard battery of allergenic extracts comprising: positive (histamine 10mg/mL) and negative controls (0.5% phenolate solution and glycerinated solution), Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (Dpt), Blomia tropicalis (Bt), Periplaneta americana (Pa), Blatella germanica (Bg), dog dander, cat dander, fungi, and grass pollen mix extracts (FDA Allergenic®, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). SPT was considered positive to a specific allergen if the mean wheal diameter was equal or higher than 3mm in the presence of a negative control equal to zero and positive control of at least 3mm.13 Adolescents who had a positive test to at least one of the allergens evaluated were considered sensitised.

Statistical analysisComparisons between the prevalence of asthma and related symptoms according to gender, as well as SPT results and CQ data between asthmatic and non-asthmatic adolescents were performed by univariate analysis. Factors with p-value lower than 0.2 were included in the binary logistic regression analysis (Backward stepwise). p-Values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. SPSS® 15.0 software (Chicago, IL, USA) was used to obtain odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), as well as to conduct univariate and multivariate analyses.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee in Research of Sao Paulo Federal University.

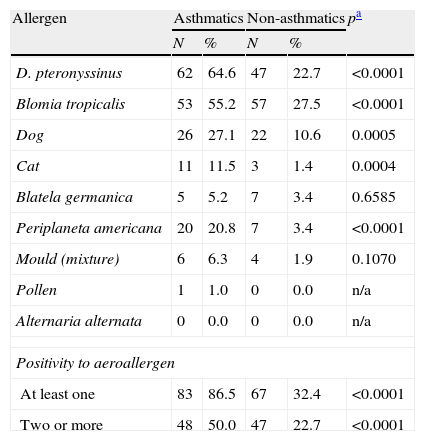

ResultsSeventeen adolescents were excluded from the initial sample due to inadequacy of the WQ. Of the 3708 remaining, 52% were females. Except for having had more than four asthma attacks, speech problem, and having had asthma diagnosed by a physician, the prevalence of asthma was significantly higher among the females in comparison to the males (Table 1). The mean prevalences were 20.7%, 6.0%, and 29.3% for active asthma, severe asthma and physician-diagnosed asthma, respectively (Table 1). A subgroup of adolescents answered the CQ: 254 non-asthmatic and 126 asthmatics. Table 2 shows the frequency of positive skin tests to aeroallergens in asthmatic and non-asthmatic adolescents. The prevalence of sensitisation to D. pteronyssinus, Blomia tropicalis, dog dander, cat dander, and Periplaneta americana were significantly higher among asthmatics (Table 2). Sensitisations to at least one or to two or more aeroallergens were significantly higher among the asthmatics (Table 2).

Adolescents (13–14 yrs) with affirmative answers to the International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Childhood (ISAAC) written questionnaire (Asthma Module), according to gender in Belem, Amazon region.

| Question | Male N (%) | Female N (%) | Total N (%) | pa M×F |

| Wheezing ever | 627 (35.2) | 808 (42.0)* | 1434 (38.7) | <0.0001 |

| Wheezing last 12 months | 333 (18.7) | 435 (22.6)* | 767 (20.7) | 0.0039 |

| Wheezing attacks last 12 months | ||||

| 1–3 | 286 (16.0) | 405 (21.0)* | 690 (18.6) | 0.0004 |

| >4 | 59 (3.3) | 66 (3.4) | 126 (3.4) | |

| Sleep disturbance last 12 months | 149 (8.4) | 272 (14.1)* | 423 (11.4) | <0.0001 |

| Difficult to speech last 12 months | 93 (5.2) | 129 (6.7) | 222 (6.0) | 0.0677 |

| Asthma ever | 536 (30.1) | 550 (28.6) | 1086 (29.3) | 0.3264 |

| Wheezy with exercise last 12 months | 368 (20.7) | 468 (24.3)* | 834 (22.5) | 0.0089 |

| Cough at night last 12 months | 787 (44.2) | 1107 (57.5)* | 1895 (51.1) | <0.0001 |

Frequency of sensitisation to aeroallergens in asthmatic (N=96) and non-asthmatic (N=207) adolescents identified by the International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Childhood (ISAAC) protocol in Belem, Amazon region.

| Allergen | Asthmatics | Non-asthmatics | pa | ||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| D. pteronyssinus | 62 | 64.6 | 47 | 22.7 | <0.0001 |

| Blomia tropicalis | 53 | 55.2 | 57 | 27.5 | <0.0001 |

| Dog | 26 | 27.1 | 22 | 10.6 | 0.0005 |

| Cat | 11 | 11.5 | 3 | 1.4 | 0.0004 |

| Blatela germanica | 5 | 5.2 | 7 | 3.4 | 0.6585 |

| Periplaneta americana | 20 | 20.8 | 7 | 3.4 | <0.0001 |

| Mould (mixture) | 6 | 6.3 | 4 | 1.9 | 0.1070 |

| Pollen | 1 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | n/a |

| Alternaria alternata | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | n/a |

| Positivity to aeroallergen | |||||

| At least one | 83 | 86.5 | 67 | 32.4 | <0.0001 |

| Two or more | 48 | 50.0 | 47 | 22.7 | <0.0001 |

Table 3 summarises factors (risk/protective) associated to the development of asthma and identified by logistic regression.

Factors associated with the development of asthma in adolescents in the city of Belem, Amazon region, identified by logistic regression.

| Factor | N | Exposed N (%) | OR (95% CI) | p |

| Have had tuberculosis | 377 | 16 (4) | 38.9 (4.6–328.0) | <0.0001 |

| Tiled floor today | 375 | 29 (8) | 5.1 (2.5–10.1) | <0.0001 |

| Have had measles | 377 | 38 (10) | 4.7 (2.3–9.8) | 0.0402 |

| Breastfeeding ever | 380 | 123 (32) | 4.2 (1.1–15.2) | 0.0213 |

| Juice in the diet (once a week) | 372 | 78 (21) | 3.4 (1.5–8.3) | 0.00123 |

| Current allergic rhinitis | 380 | 97 (26) | 3.2 (1.8–5.9) | 0.0043 |

| Foam pillow today | 380 | 86 (23) | 2.4 (1.4–4.5) | 0.0009 |

| Breastfeeding>6 months | 380 | 75 (20) | 2.1 (1.2–3.7) | 0.0206 |

| Tobacco smoke at home | 380 | 41 (11) | 2.4 (1.2–4.5) | 0.0221 |

| Moisture in home today | 378 | 64 (17) | 1.8 (1.1–3.2) | 0.0237 |

| Diagnosis of allergic rhinitis | 379 | 65 (35) | 1.7 (1.2–2.9) | 0.0032 |

| Foam pillow (1st yr) | 372 | 1 (0) | 0.4 (0.2–0.9) | 0.0133 |

| Cooling house today | 380 | 59 (16) | 0.4 (0.2–0.8) | 0.0072 |

| Cat (1st yr) | 380 | 6 (2) | 0.2 (0.1–0.7) | <0.0001 |

| Raw vegetables (once a week) | 368 | 6 (2) | 0.1 (0.0–0.4) | <0.0001 |

OR: odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

The prevalence of active asthma in adolescents in Belem was 20.7%, i.e., higher than the world and Latin American mean prevalences (14.1% and 15.9%, respectively),14 but close to that of Brazil (19.0%).6 An inverse relationship between latitude and prevalence of asthma has been previously documented; however other Brazilian cities in the south and southeast regions also have high prevalence rates. Perhaps the geographic influence would be justified by the fact that the city's location determines specific characteristics: climatic (temperature, relative humidity and rainfall), socioeconomic (economic development, urbanisation) and cultural (diet, ethnicity, language), which could be risk or protective factors, thus justifying the variation in prevalence. The higher relative humidity, due to the geographic location, would be related to increased atopic sensitisation and increased emergency care and hospitalisation for asthma.15,16,7

Another point to comment is the dissociation of the results to active asthma (20.7%) and physician-diagnosed asthma (29.3%), suggesting an “overdiagnostic” situation in regards to asthma in Belem. This fact differs from other regions in Brazil, where the term “asthma” carries more stigmas by the population and only half of the patients are identified as asthmatic.6 Probably Question #6 of the ISAAC written questionnaire (Have you ever had asthma?) is probably more susceptible to regional differences in diagnostic practices, whether related to cultural acceptance of the term asthma by the population or even by a “trivialisation” of asthma diagnosis by doctors.17 Similar to other studies, there was a predominance of asthma among female adolescents, possibly secondary to clinical and immunological responses, directly related to hormonal changes at that age.18

Background infections such as tuberculosis and measles were identified as risk factors (OR=38.9 and 4.7, respectively) for the development of asthma in adolescents in this study.

In Brazil, tuberculosis is a highly prevalent disease, and the country ranks at the 16th position worldwide. The number of new cases in Brazil is 38.2/100,000 inhabitants, whilst in the city of Belem, marked by social inequality, and possibly by the low quality of the Public Health Care, this rate reaches values of up to 80 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. This situation can justify the results obtained in this study.19

These data are opposite to those previously observed by von Mutius et al. which showed an inverse relationship between the notification of tuberculosis and the prevalence of asthma.20 An ecological study using data from Brazilian centres from ISAAC Phase I did not confirm these results.21

Recent data, however, start to show possible explanations for this paradox, indicating that sub-products of certain microorganisms (some atypical bacteria) could stimulate the synthesis of IL-18, which activate differentiated Th1 lymphocytes (“super Th1”), which may release Th2-like cytokines and cause an inflammatory response, for example, asthma.22

Although the nutritional, immune and emotional benefit of breastfeeding is unquestionable in the first months of life, its protective effect in asthma development is still controversial and seems to be more evident in individuals with a family history of atopy.23 Sears et al. followed 1037 children from birth to 26 years, with assessments every two years. Of this total, 504 (49%) were breastfed for at least four weeks and had a higher prevalence of asthma at nine (p=0.0008) and 26 years (p<0.001) when compared to non-breastfed subjects.24

In this study, the history of breastfeeding for any length of time (OR=4.2, IC 95%: 1.1–15.2) or for at least six months (OR=2.1, IC 95%: 1.2–3.7) were risk factors for asthma.

The prevalence of breastfeeding in children under six months in Brazil is 41%, and in Belem it reaches 56.1%.25 So, for our centre, it is possible that breastfeeding represents a statistical bias, and turns out to be a disease marker. Moreover, it is possible that children with risk for atopy were more breastfed, in order to avoid expression of the disease, which may lead to breastfeeding being unintentionally identified as a risk variable for the future development of asthma.

Exposure to tobacco smoke was identified as a risk factor (OR=2.4, IC 95%: 1.2–4.5) which confirms the observation of classical studies.26 The consistency in studies investigating postnatal exposure to active or passive tobacco smoke leaves no doubt that this is an unconditional risk factor for the development of respiratory allergies in children and adolescents. Therefore, avoiding smoking will always be effective and of fundamental importance as a strategy for primary and secondary prevention of respiratory allergies.

The individual analysis of some studies with specific dog and cat allergens has raised many questions, as there are different designs, selection biases, and therefore, ambiguous conclusions. Some of them suggest that exposure to these animals was associated with increased risk of allergic sensitisation while others suggest low risk. In this study, the presence of a cat inside the house, especially in the first months of life, was identified as a protective factor for developing asthma (OR=0.2, IC 95%: 0.1–0.7). It is probable that early exposure to high levels of cat allergen (Fel d 1) can induce the phenomenon of immune tolerance and thus be a protective factor against the development of allergies.4,27 However, for a better standard of scientific evidence, some issues remain to be clarified, such as: What pet would be more or less allergenic? Also, which would be a protective factor or a risk factor? When should the first contact happen (timing)? And finally, how often should an individual be exposed to the animal?

More recently, changes to Western lifestyle induced important modifications in diet, particularly lowering the intake of antioxidant foods, especially vitamins (A, C and E) and carotenoids. This low intake could be a risk factor for allergic sensitisation and the development of childhood asthma.28 The present study shows that the ingestion of raw vegetables (OR=0.1, IC 95%: 0.0–0.4) was identified as protective for the development of asthma. A recent large study confirmed the consumption of fresh fruits and juices, fish and green vegetables as protective factors for the development of current wheezing, featuring a dietary pattern similar to the “Mediterranean Diet”.29

As documented by others, rhinitis was identified as an important risk factor for the development of asthma among the adolescents evaluated in this study.30,31

Although atopic sensitisation was more common among asthmatics, it was not identified as a risk factor for the development of asthma. It is noteworthy that the diagnosis of atopy based on a positive skin test must also take into account the medical history and symptoms of each patient, because positive skin tests among non-asthmatic individuals can be as high as 30%. Sarinho et al.,32 assessing adolescents in Northeast Brazil, found 33.3% of positive skin tests were among non-asthmatics, as well as in the present study, where 32.4% of adolescents without asthma had at least one positive skin test and 22.7% were positive for two or more allergens.

Another point to comment is the lower frequency of sensitisation to fungi in this study in comparison to that observed in the southeast and northeast of Brazil.32,33 However, the warmer and more humid climate of the northern region should harbour a higher level of domestic fungi and, therefore, greater expression in allergic sensitisation. Two distinct possibilities can explain this fact. We would not be testing the fungus actually prevalent in our region, and therefore, specific studies to determine this fungal microbiota would be needed. Additionally, while the heat and humidity favour the growth of fungal species, the same impact is observed with mites, which are major sensitising agents for respiratory allergies.

In conclusion, the questions generated in the discussion probably still do not have a precise and definitive answer, because, even today, there is no consensus on various aspects of asthma, from its definition and phenotypic variants, to its aetiology and pathophysiology. Since we may be faced with different phenotypes of “asthma”, there might be different risk factors or protective factors for each patient, according to their respective genetic background and the surrounding environment.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human subjects in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre, on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestI declare that I do not have any conflict of interest in this study. I have personally participated in every step throughout this study, from its design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, to the drafting of the final manuscript.