In our country, the prevalence and the factors associated to peanut allergy are unknown, a health problem that has been emerging worldwide.

ObjectiveTo establish the prevalence and the factors that are associated to peanut allergy amongst school children.

MethodsThis is a population-based cross-sectional study. We included 756 children aged 6–7 years. The children's parents were questioned about their peanut intake habits. A structured questionnaire was applied, it included questions regarding peanut intake; family and personal history of asthma; rhinitis; and atopic dermatitis. Allergic reactions to peanuts were registered as: probable, convincing and systematic. The statistical analyses included logistical regression models to look for associated factors.

ResultsMales were 356/756 (47.1%). Peanut allergy prevalence: probable reaction: 14/756 (1.8%), convincing reaction: 8/756 (1.1%) and systemic reaction: 3/756 (0.4%). Through multivariate analysis, the presence of symptoms of allergic rhinitis (OR=4.2 95% CI 1.3–13.2) and atopic dermatitis (OR=5.2; 95% CI 1.4–19.5) during the previous year, showed significant association to probable peanut reaction. The former year, the presence of atopic dermatitis was the only variable that was substantially associated to a convincing reaction (OR=7.5; 95% CI 1.4–38.4) and to a systematic reaction (OR=45.1; 95% CI 4.0–510.0), respectively.

ConclusionsThe reported prevalence of peanut allergy was consistent with that found in previous studies; symptoms of allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis were identified as associated factors to peanut allergy.

The prevalence for the perception of food allergy in children ranges from 3.9% to 8.0%.1–3 Some studies have shown a significant increase in the past few years for food allergy prevalence, amongst these, peanuts are one of the most common foods.1,4,5

Peanut allergy in children has been linked to various factors, such as, family history of peanut allergy, personal history of dermatitis, the topical use of compositions based on peanut oil and the exposure to soy proteins.6 Other causes, such as the amount of peanut intake, also increase the probability of developing an allergy to these types of foods.7 However, its early introduction to the diet of infants, is reflected in a lower frequency.8 Although perinatal factors, such as breastfeeding9 and the manner in which the child was born,10 have been associated to allergic illnesses, their connection to peanut allergy has been less explored.

In our country, the epidemiological profile for peanut allergy is unknown for Mexican children; this represents a problem if we consider that there is a change in the intake pattern of peanuts between industrialised and non-industrialised countries.

This study describes the prevalence of a probable reaction, a convincing reaction and a systematic reaction to peanuts amongst school-aged children; as well as the factors associated with each type of reaction.

MethodsEthicsThe parents of each child signed a written consent form so that their child could participate. The Ethical Research Committee to which the head researcher is ascribed approved this study. Furthermore, this study was approved by Jalisco's Department of Education; which enabled us to apply this study in schools.

DesignIn this cross-sectional study, we used a sample size of 756 children aged 6–7; they were enrolled in elementary schools located within the city of Guadalajara, in the Mexican state of Jalisco.

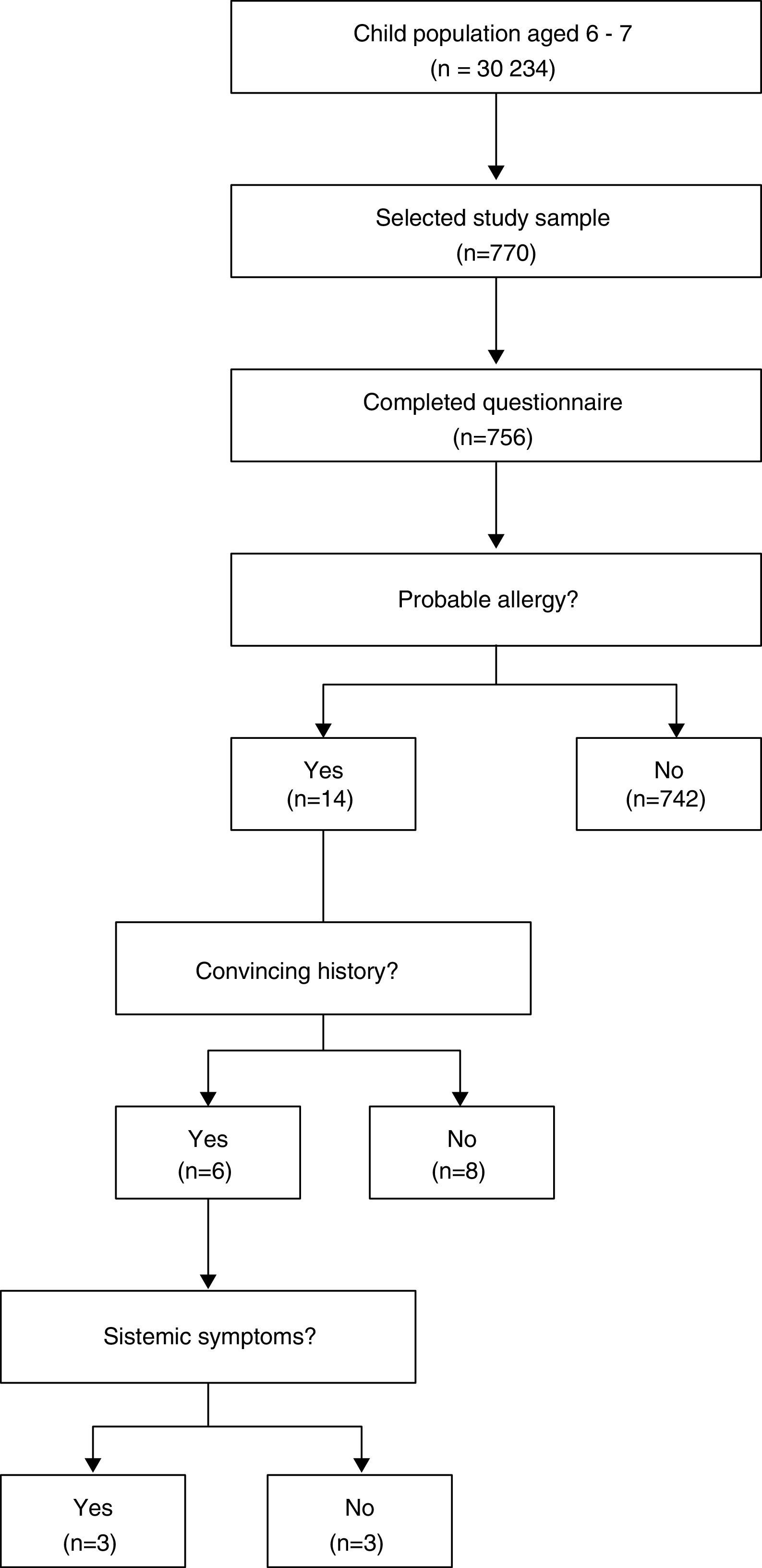

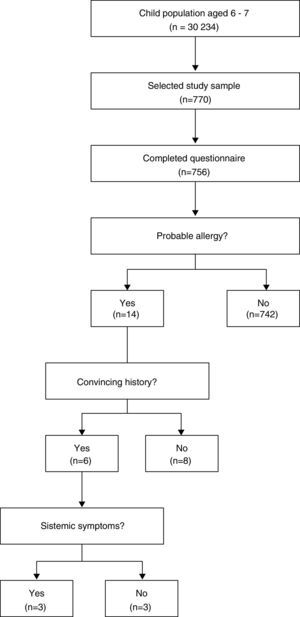

Sample sizeThe initial participant pool consisted of 30,234 children, distributed throughout 205 public and private schools during the 2013–2014 term; for a confidence interval of 95%, a permitted margin of error of 1% and an expected frequency of 2% for hyper-sensibility to peanut,11 the final sample included 770 children.

Sample type and descriptionThe participants were incorporated through a conglomerate sampling from April to December 2014, Fig. 1.

The city of Guadalajara is divided into seven administrative zones; these were taken as strata and within each of these a sub-sample was calculated based on the number of enrolled students. Through random selection, at least one school per zone was selected for the sub-sample, and in case it did not meet the required size estimate, we continued to randomly select schools until the sample size was completed.

QuestionnaireThe questionnaire included questions associated to peanut exposure, intake patterns and discomfort linked to peanut allergy; moreover, subjects were asked about their family medical history regarding parent allergic disease; in order to detect asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis, as well as their symptoms during the previous year of the child's life, we used The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood.12

Definitions of allergic reactions to peanutWe considered a probable allergic reaction to peanut if the subject answered affirmatively to the question: Does your child (a) have some type of discomfort, reaction or symptom after ingesting a peanut or foods with peanuts? A convincing allergic peanut reaction was recorded if after having answered affirmatively to the previous question; the affected organs and symptoms were commonly observed in allergic reactions (skin: urticaria and angio-oedema; respiratory symptoms: difficulty breathing, wheezing and throat oppression; gastrointestinal system: vomiting and diarrhoea) and if it began within two hours after having ingested peanuts.5,13 Additionally, if the aforementioned were present and two or more organs or systems were affected, the allergic peanut reaction was considered to be systemic.

AnalysesThe IBM SPSS programme, version 20.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to analyse the data. In order to obtain the estimation of peanut allergy proportion its frequency was determined. For continuous variables with a normal distribution, we calculated their mean and their standard deviation. For quantitative variables that did not show a normal distribution, the median was calculated, and during its comparison we used the Mann–Whitney U Test. Additionally, categorical variables were expressed as proportions with their respective confidence intervals at 95% (95% CI).

To identify the factors associated with peanut allergy, we developed three multivariate models in which the dependent variables were: the probable reaction, the convincing reaction and the systemic reaction, respectively. In all the models the independent covariates were: personal history of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis; as well as the presence of symptoms for asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis 12 months prior to the day of the interview; additionally, in each model the medical history of a relative with atopy was included, as was the sex variable. The risks were calculated through binary logistical regression with the conditional forward method.

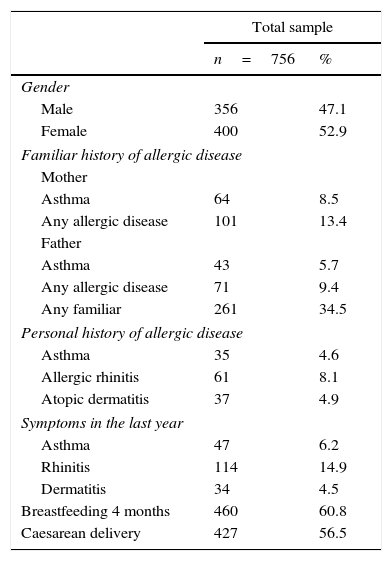

ResultsThe clinical characteristics of the test subjects are described in Table 1. 756 subjects were included, of whom 356 were male (47.1%). The prevalence of a family history of asthma and allergic disease in either parent was similar (5.7% vs. 8.5%). Atopy co-morbidity was more frequent in children with allergic rhinitis; during the previous year, 14.9% of the children had rhinitis symptoms. A history of breastfeeding for at least four months was of 67.2%. A little over half of the children had been delivered through caesarean section.

Clinical characteristics of the study's population.

| Total sample | ||

|---|---|---|

| n=756 | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 356 | 47.1 |

| Female | 400 | 52.9 |

| Familiar history of allergic disease | ||

| Mother | ||

| Asthma | 64 | 8.5 |

| Any allergic disease | 101 | 13.4 |

| Father | ||

| Asthma | 43 | 5.7 |

| Any allergic disease | 71 | 9.4 |

| Any familiar | 261 | 34.5 |

| Personal history of allergic disease | ||

| Asthma | 35 | 4.6 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 61 | 8.1 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 37 | 4.9 |

| Symptoms in the last year | ||

| Asthma | 47 | 6.2 |

| Rhinitis | 114 | 14.9 |

| Dermatitis | 34 | 4.5 |

| Breastfeeding 4 months | 460 | 60.8 |

| Caesarean delivery | 427 | 56.5 |

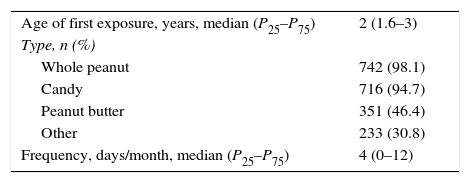

Table 2 shows the peanut intake pattern. The median age in which children ate peanuts for the first time was two years old. Almost all of the participants had ingested whole peanuts or products that contained them at least four days or more per month.

The probable reaction frequency during the first peanut ingestion was observed in five children (1.9%; 95% CI: 0.2–3.6%), of these, three continued to test positive until they reached school age (60%). Therefore, the probable prevalence of peanut allergy during ages 6–7 was 14/756 (1.8%; 95% CI: 1.1–3.1%), of whom, 8/756 (1.1%; 95% CI: 0.5–2.1%) had a convincing history of the allergy and 3/756 (0.4%; 95% CI: 0.1–1.2%) had a systematic reaction.

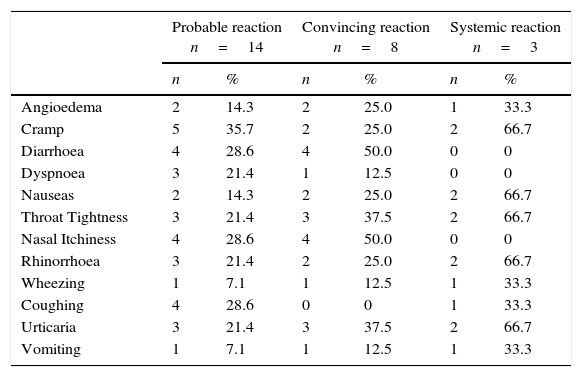

The symptoms that were more habitually associated with a probable peanut reaction were intestinal discomfort, cramps, diarrhoea, then nasal itchiness and coughing, Table 3. In the convincing reaction, the symptoms were diarrhoea and nasal itchiness; in the systemic reaction, they were urticaria, cramps, rhinorrhoea, throat tightness and nausea.

Frequency of symptoms related to peanut allergy.

| Probable reaction n=14 | Convincing reaction n=8 | Systemic reaction n=3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Angioedema | 2 | 14.3 | 2 | 25.0 | 1 | 33.3 |

| Cramp | 5 | 35.7 | 2 | 25.0 | 2 | 66.7 |

| Diarrhoea | 4 | 28.6 | 4 | 50.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dyspnoea | 3 | 21.4 | 1 | 12.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Nauseas | 2 | 14.3 | 2 | 25.0 | 2 | 66.7 |

| Throat Tightness | 3 | 21.4 | 3 | 37.5 | 2 | 66.7 |

| Nasal Itchiness | 4 | 28.6 | 4 | 50.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rhinorrhoea | 3 | 21.4 | 2 | 25.0 | 2 | 66.7 |

| Wheezing | 1 | 7.1 | 1 | 12.5 | 1 | 33.3 |

| Coughing | 4 | 28.6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 33.3 |

| Urticaria | 3 | 21.4 | 3 | 37.5 | 2 | 66.7 |

| Vomiting | 1 | 7.1 | 1 | 12.5 | 1 | 33.3 |

The mean age of the first peanut ingestion in children with a probable reaction to peanuts did not differ from those that did not have a reaction to it (2.2±1.3 years vs. 2.5±1.2 years, P=0.396); a similar pattern was observed for the convincing reaction (2.0±1.4 years vs. 2.5±1.2 years, P=0.254); in contrast, children with a systemic reaction manifested it at an earlier age than their counterparts (1.0±0 years vs. 2.5±1.2 years, P=0.034).

The median number of days in which peanuts were ingested per month in the probable reaction group did not differ from that of children without a reaction (8 days vs. 4 days, P=0.832); nor was this seen in the convincing reaction group (6 days vs. 4 days, P=0.464), the same is true for the systemic reaction group (8 days vs. 4 days, P=0.756).

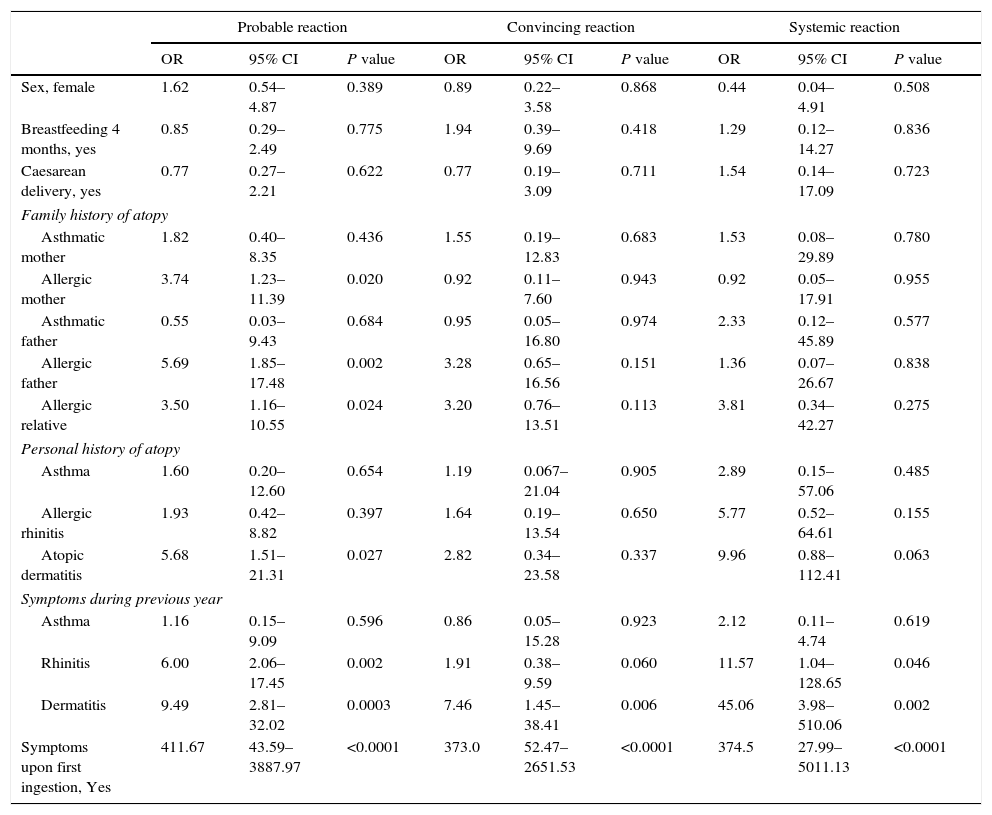

When compared to children that did not have an allergic reaction to peanuts, the history of an allergic mother (OR=3.74; P=0.020), an allergic father (OR=5.69; P=0.002) or another allergic relative (OR=3.50; P=0.024), there was considerable association to a probable peanut allergy, as with those that had a personal history of atopic dermatitis (OR=5.68; P=0.027) and with a presence of nasal symptoms (OR=6.0; P=0.002) along with dermatitis during the previous year OR=9.49; P=0.0003), Table 4. Children with a convincing reaction showed an association to the presence of cutaneous symptoms in the previous year (OR=7.46; P=0.006). Lastly, those who had a systemic reaction were associated to the presence of nasal symptoms (OR=11.57; P=0.046) and dermatitis symptoms (OR=45.06; P=0.002) in the prior year. The three models for peanut allergy were strongly linked to the history of symptoms identified during the child's first ingestion of peanuts.

Factors associated to peanut allergy.

| Probable reaction | Convincing reaction | Systemic reaction | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Sex, female | 1.62 | 0.54–4.87 | 0.389 | 0.89 | 0.22–3.58 | 0.868 | 0.44 | 0.04–4.91 | 0.508 |

| Breastfeeding 4 months, yes | 0.85 | 0.29–2.49 | 0.775 | 1.94 | 0.39–9.69 | 0.418 | 1.29 | 0.12–14.27 | 0.836 |

| Caesarean delivery, yes | 0.77 | 0.27–2.21 | 0.622 | 0.77 | 0.19–3.09 | 0.711 | 1.54 | 0.14–17.09 | 0.723 |

| Family history of atopy | |||||||||

| Asthmatic mother | 1.82 | 0.40–8.35 | 0.436 | 1.55 | 0.19–12.83 | 0.683 | 1.53 | 0.08–29.89 | 0.780 |

| Allergic mother | 3.74 | 1.23–11.39 | 0.020 | 0.92 | 0.11–7.60 | 0.943 | 0.92 | 0.05–17.91 | 0.955 |

| Asthmatic father | 0.55 | 0.03–9.43 | 0.684 | 0.95 | 0.05–16.80 | 0.974 | 2.33 | 0.12–45.89 | 0.577 |

| Allergic father | 5.69 | 1.85–17.48 | 0.002 | 3.28 | 0.65–16.56 | 0.151 | 1.36 | 0.07–26.67 | 0.838 |

| Allergic relative | 3.50 | 1.16–10.55 | 0.024 | 3.20 | 0.76–13.51 | 0.113 | 3.81 | 0.34–42.27 | 0.275 |

| Personal history of atopy | |||||||||

| Asthma | 1.60 | 0.20–12.60 | 0.654 | 1.19 | 0.067–21.04 | 0.905 | 2.89 | 0.15–57.06 | 0.485 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 1.93 | 0.42–8.82 | 0.397 | 1.64 | 0.19–13.54 | 0.650 | 5.77 | 0.52–64.61 | 0.155 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 5.68 | 1.51–21.31 | 0.027 | 2.82 | 0.34–23.58 | 0.337 | 9.96 | 0.88–112.41 | 0.063 |

| Symptoms during previous year | |||||||||

| Asthma | 1.16 | 0.15–9.09 | 0.596 | 0.86 | 0.05–15.28 | 0.923 | 2.12 | 0.11–4.74 | 0.619 |

| Rhinitis | 6.00 | 2.06–17.45 | 0.002 | 1.91 | 0.38–9.59 | 0.060 | 11.57 | 1.04–128.65 | 0.046 |

| Dermatitis | 9.49 | 2.81–32.02 | 0.0003 | 7.46 | 1.45–38.41 | 0.006 | 45.06 | 3.98–510.06 | 0.002 |

| Symptoms upon first ingestion, Yes | 411.67 | 43.59–3887.97 | <0.0001 | 373.0 | 52.47–2651.53 | <0.0001 | 374.5 | 27.99–5011.13 | <0.0001 |

OR: odds ratio; 95% CI: confidence interval at 95%.

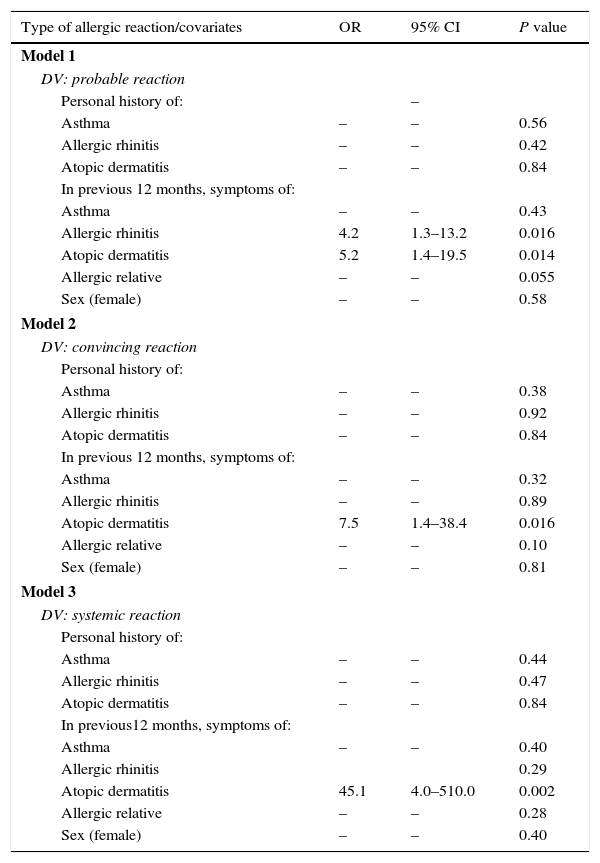

In Table 5, the three multivariate models are summarised to identify the factors associated to peanut allergy. Model 1 was adjusted according to a personal history of atopic diseases, or the presence of an allergic family member and by sex; the presence of allergic rhinitis symptoms (OR=4.2; 95% CI: 1.4–19.5) in children 12 months prior to the interview showed a significant association to a probable reaction to peanuts. After having adjusted models 2 and 3 with the rest of the covariates, they showed that the presence of symptoms for atopic dermatitis was the only variable considerably linked to a convincing reaction (OR=7.5%; 95% CI: 1.4–38.4) and a systemic reaction (OR=45.1; 95% CI: 4.0–510.0), respectively.

Multivariate model of factors associated to peanut allergy.

| Type of allergic reaction/covariates | OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||

| DV: probable reaction | |||

| Personal history of: | – | ||

| Asthma | – | – | 0.56 |

| Allergic rhinitis | – | – | 0.42 |

| Atopic dermatitis | – | – | 0.84 |

| In previous 12 months, symptoms of: | |||

| Asthma | – | – | 0.43 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 4.2 | 1.3–13.2 | 0.016 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 5.2 | 1.4–19.5 | 0.014 |

| Allergic relative | – | – | 0.055 |

| Sex (female) | – | – | 0.58 |

| Model 2 | |||

| DV: convincing reaction | |||

| Personal history of: | |||

| Asthma | – | – | 0.38 |

| Allergic rhinitis | – | – | 0.92 |

| Atopic dermatitis | – | – | 0.84 |

| In previous 12 months, symptoms of: | |||

| Asthma | – | – | 0.32 |

| Allergic rhinitis | – | – | 0.89 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 7.5 | 1.4–38.4 | 0.016 |

| Allergic relative | – | – | 0.10 |

| Sex (female) | – | – | 0.81 |

| Model 3 | |||

| DV: systemic reaction | |||

| Personal history of: | |||

| Asthma | – | – | 0.44 |

| Allergic rhinitis | – | – | 0.47 |

| Atopic dermatitis | – | – | 0.84 |

| In previous12 months, symptoms of: | |||

| Asthma | – | – | 0.40 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 0.29 | ||

| Atopic dermatitis | 45.1 | 4.0–510.0 | 0.002 |

| Allergic relative | – | – | 0.28 |

| Sex (female) | – | – | 0.40 |

DV: dependent variable.

OR: Odds Ratio obtained through logistical regression using Forward Conditional Method.

The ORs are not calculated for variables excluded from the model.

All covariates were categorical (with and without the characteristic of interest).

It is our understanding that this is the first population study carried out in Mexico that establishes the peanut allergy prevalence amongst children aged 6–7 years, for this study we adopted the definition used in previous epidemiological studies.3,13–16 The results indicate that 1.8% and 1.1% of the parents noted that their children had a probable and convincing history of peanut allergy, respectively; moreover, it was observed that a secondary systemic reaction associated to peanut ingestion was present in 0.4% of the studied population. Another noteworthy finding is that the presence of symptoms of dermatitis during the previous year was significantly associated with peanut allergy.

Although Mexico is not one of the countries with the highest production or intake of peanuts, it is interesting to note that its prevalence for a convincing peanut allergy was found to be similar to that of countries with a higher intake. For example, Ben-Shoshan et al.15 observed that a history of convincing peanut allergy in children was of 0.93% (95% CI: 0.74–1.12%); in another study, Shek et al.16 children aged 4–6 and 14–16, denoted a frequency of 0.64% and 0.47%, respectively. More recently, Dyer et al.17 carried out an epidemiological study in children across the United States, and it was observed that the occurrence of peanut allergy was 2.0%, however, when we limit the observation to children aged 6–10, the result was 0.5%. In Europa, Nwaru et al., through a meta-analysis, showed the overall lifetime prevalence of self-reported peanut allergy was 0.4% for point self-reported prevalence, 1.7%.18 In some regions throughout the globe, peanut allergy prevalence has been modified; Sicherer et al.5 undertook a telephone survey during three different periods, this led to changes in the increase of peanut allergy prevalence, in 2008 it was at 1.4% (95% CI: 1.0–1.9%) in 2003 it was at 0.8% (P non-significant) and in 1997 it was at 0.4% (P<0.0001). On the other hand, Venter et al.11 studied three cohorts of children born in the same geographical zone, the Isle of Wight in the United Kingdom, and proved that the prevalence for the sensitisation of peanuts increased from 1.3% to 3.3% in the cohorts from 1989 and 1994–1996 (P=0.003), after which the prevalence dropped until reaching 2.0% (cohort 2001–2002), although the decrease did not reach significant statistical importance (P=0.145); with regard to the clinical peanut allergy, a considerate increase was seen in the cohorts after passing 0.5–1.4% (P=0.023) with a later decrease to 1.2%, while this was not statistically significant (P=0.850), correspondingly. As far as we know, no previous research can be found in Mexico that would allow us to evaluate possible tendencies in the modification of the prevalence for peanut allergy amongst children, which is why this study has become the starting point for observing such changes.

The prevalence for peanut allergy observed in our study, is likely associated to our peanut intake habits or its products, although the parents of the children that had some sort of reaction to peanuts indicated that their children had consumed them on a more regular basis than their non-reactive counterparts; this fact did not account for any statistical significance. The influence of the ingestion pattern and the development of peanut allergy in children had been previously documented by Du Toit et al.,7 where it was noted that the prevalence for peanut allergy in children that lived in the United Kingdom was more common than for those that lived in Israel, and that the discrepancy was due to an earlier introduction, as well as a higher intake of peanuts amongst Israeli children rather than children in the United Kingdom. Recently, Du Toit et al.8 also demonstrated that in high-risk children, the early ingestion of peanuts was linked to a lower probability of developing and allergy to them. Prior to that, Poole et al.19 and Koplin et al.20 had noted that a later introduction of wheat and egg into a child's diet was associated to a higher risk of wheat and egg allergies, respectively. In Mexican children with peanut allergy, evidenced through a positive oral challenge test, they had a later peanut consumption than their counterparts without allergy (OR: 8.0, P=0.026).21 These findings lead us to believe that an early introduction into a solid-food diet could be reflected in lower food allergy frequencies. Moreover, our study found that children that had a systemic reaction to peanut ingestion, had ingested it at an earlier point in their lives (1 year old) than those that did not have a systemic reaction to peanuts (2.5 years), therefore, it seems plausible to suggest that if someone intended to develop a certain degree of tolerance to peanuts, they should be ingested prior to the first year of age,8 since a later introduction seems to become a productive agent for systemic symptoms.

In our study, the frequency of clinical manifestations related to peanuts varied according to the type of reaction. In a recent epidemiological study carried out in the United States, 754 children were found to have peanut allergy, these most common clinical manifestations were cutaneous (hives, oedema in the lips, eyes or face), and followed by respiratory symptoms such as difficulty breathing and wheezing.17 Another study in Singapore registered the same findings, predominant manifestations in the skin (urticaria, redness in the skin and angio-oedema) as well as respiratory discomfort (coughing, difficulty breathing and wheezing).22 It is likely that the differences in age amongst the children that were studied, or in the parents’ perception of the children, affect the different clinical behaviours associated to peanut allergy. On the other hand, the frequency of systemic reactions associated to the ingestion of peanuts was similar to that recently reported in North America.17

Several factors have been associated to the peanut allergy described here. In our study, we explored the role that breastfeeding and caesarean deliveries play in peanut allergy; we found no evidence between these. This is likely due to the fact that such elements have been implied in the development of allergic diseases and not the actual process behind the allergy that usually follows. Thus far, family medical history has been the most constant factor when it comes to asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis, however, its association to food allergies has been less explored and the available results are inconsistent. The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children proved that a maternal history of asthma or atopy was significantly associated to the probability of testing positive to a peanut allergy.6 Thus, in Health Nuts Study it was observed that the association of asthma and allergic rhinitis in either parent was associated to peanut allergy.23 Recently, The Consortium of Food Allergy Research Observational Study analysed the role that maternal or paternal heredity play in peanut allergy, although no significant statistical association was found.24 In our study, through the use of three models used to evaluate peanut allergy and its relation to the history of allergic diseases, we found that a probable reaction was linked to a paternal history as well as an allergic family member, with regard to personal medical history, atopic dermatitis is where we found an association; perhaps this behaviour is due to the lack of specifications in questions asked to detect a probable allergic reaction to peanuts. It should be noted that during the previous year the presence of rhinitis or dermatitis symptoms, and not asthma symptoms, were associated to some of the peanut allergy models. Allergic rhinitis was linked to a probable and systemic reaction; this could be the result of a possible overlapping reaction between pollens and some proteins found in peanuts25; singularly, dermatitis symptoms during the prior year were significantly associated to all peanut allergy models. These findings can be seen online along with the recently presented results that show how children with atopic dermatitis had a higher probability of sensitisation to peanut (OR: 1.97, P=0.01) or peanut allergy (OR: 2.34, P=0.01). This supports the possibility that environmental exposure to peanuts over damaged skin plays a relevant role in the peanut allergy process.24 Another revealing find showed that children with atopic dermatitis had a higher probability of systemic reactions with peanut exposure, to our knowledge, this had not been previously reported in our population, and it highlights the importance of observing these children. Additionally, consumption of peanut during the first months of pregnancy,26,27 day-care attendance within the first months of life and having greater number of sibling28 have been linked to lower risk of peanut allergy.

It was interesting to have observed the presence of symptoms during a child's first ingestion of peanuts, this served as an indicator of peanut allergy, in this sense, we believe that there are two additional modes to the oral way that allow peanut sensitisation. This was previously documented by Fox et al.29; they showed that sensitisation to peanuts may have occurred as a result of environmental exposure, either through the skin or inhalation, here, higher levels of exposure were associated to greater allergy risks.

Limitations and strengthsIt is important to note that this study has several limitations. First, as the surveys were sent out through children so that their parents could answer them, we cannot be certain that the actual parents answered these surveys. In addition, a possible recall bias could have been introduced because the difficulty of recalling allergic reactions may have been different between parents with or without children that have allergies. The second limitation concerns the design of our study, since it is a cross-sectional study, it does not permit us to establish a tendency for peanut allergy prevalence. Thirdly, we did not delve further into the breastfeeding factor nor did we include other matters associated to peanut allergy risk, such as the role of the history of food allergy in parents or siblings. Lastly, it was impossible to confirm a diagnosis for peanut allergy, either through the quantification of the specific IgE, skin prick test or oral challenge test; instead, the diagnosis was established by self-report.

On the other hand, the strengths of our study include a high pool of participants (98.2%), additional to an adequate sample size, and a representative sampling that allowed us to effectively determine the prevalence for peanut allergy in all forms; furthermore, as we undertook a population study, our results can be extrapolated only for those children aged between 6 and 7 years old in our city.

ConclusionsAlmost two out of every 100 children aged 6–7 manifest a probable allergic reaction to peanuts, however, only 1% of these children actually develop a convincing allergic reaction. When we compared these results, we found that they are consistent with those found in previous studies carried out across the globe. Symptoms of allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis, but not asthma, were identified as factors associated to peanut allergy. On the other hand, early and frequent consumption of peanuts are probably related to its genesis; but new studies to verify the above are required, and are also aimed at documenting the incidence of peanut allergy and our results can be extrapolated only for those children aged between 6 and 7 years old in our city.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.