Omalizumab is present in international guidelines for the control of severe asthma, but data on the long-term effects in children are limited. Our objective was to perform a ‘real-life’ long-term trial of omalizumab in children with allergic asthma.

Materials and methodsAn observational single center ‘real-life’ study was performed. Data for treatment, lung function, side effect, asthma exacerbations and hospitalizations were recorded at six months and annually.

ResultsForty-eight patients <18 years of age were enrolled. Median treatment period was 2.9 (0.5–6). Fluticasone dose for the maintenance treatment decreases significantly at six months (452mcg/day to 329.89mcg/day, respectively). This difference was maintained throughout the follow-up. Nobody used oral corticosteroid after six months. The rate of hospital admissions and visits to the emergency department for asthma exacerbations decreased significantly in the third years and fourth years follow-up, respectively. There was an improvement in lung function. Mean values of FEV1 and FEF25–75% before treatment were 79.88 and 62.94, respectively; after six months of treatment a statistically significant change was seen with a mean FEV1 of 92.29 and FEF25–75% of 76.31 (p=0.0001). Lung function values were above normal throughout the six years of treatment. No side effects were reported.

ConclusionsOverall in ‘real life’ omalizumab in children reduces asthma exacerbations and hospitalizations, improves lung function, and decreases the maintenance therapy. It is shown to be safe for up to six years of treatment in children.

Asthma continues to be an important worldwide public health issue with a profound economic and social impact. It is one of the most important chronic diseases in childhood, with its rising incidence over the past 20 years. In Spain, the prevalence of asthma is estimated at 7.1–12.9% in children 6–7 years of age and 7.1–15.3% in the 13 to 14-year-old age group.1–3

In recent years, the use of omalizumab, a humanized anti-IgE monoclonal IgG1 antibody, has risen, and it is currently included in national and international asthma guidelines such as the Global Initiative of Asthma (GINA),1 the International Consensus on Pediatric Asthma (ICON),4 and the Spanish Guide to Asthma Management (GEMA 4.0).5

Omalizumab binds to circulating IgE in the site of the IgE receptor (FcɛRI), present in basophils and mast cells. Complexes are formed, thereby decreasing circulating IgE and inhibiting the cascade of inflammatory mediators that are released during IgE-mediated allergic reactions.

Omalizumab has been proven to be effective for maintenance treatment in moderate to severe asthma. Different randomized trials6–12 and observational ‘real-life’ studies in adults13–17 have shown that the use of omalizumab lowers the rate of asthmatic exacerbations and hospitalizations, reduces the use of inhaled corticosteroids, and improves quality of life.

In pediatric populations, omalizumab has shown clinical effectiveness. Still, both randomized and real-life studies are scarce, especially in the 6–12 years of age group. For this reason, we evaluated our experience in children with severe asthma that have been treated with omalizumab in our Department since February 2007.

MethodsThis was an observational single center ‘real-life’ study describing evolution of patients treated omalizumab for severe uncontrolled asthma (GINA)1 in the Pediatric Allergy and Clinical Immunology Department at Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona. Patients were followed in our department until the age of 18.

Our primary aim was to assess the difference in asthmatic exacerbations before and during treatment with omalizumab. We also aimed to evaluate the treatment needed to maintain asthma control, the changes in lung function, and possible adverse events.

Data were collected from the hospital's electronic clinical records, as well as shared computerized databases from health centers in our network.

Demographic data, personal history of atopy, and environmental sensitization demonstrated by skin prick test were collected for each patient. Total IgE levels were determined prior to treatment. Dose, frequency of administration, and treatment period with omalizumab were recorded, as well as additional maintenance treatment including specific immunotherapy.

Exacerbations requiring visits to the emergency department and hospital admissions were collected starting from the year prior to omalizumab, six months after starting treatment, and then annually. Data were recorded per 100 patients/year.

Maintenance treatment and lung function were recorded at baseline, at six months after starting omalizumab, and on an annual basis. Mean dose of inhaled corticosteroid (IC), the number of patients using long-acting beta agonists (LABA) and oral steroids were recorded. The doses of the different ICs were equaled to fluticasone, using the GINA guide IC dose table as the reference.1

Spirometric values (FEV1 and FEF25–75%) were recorded. Normal reference values used were based on the SEPAR (Sociedad española de neumología y cirugía torácica) recommendations,18 considering alterations in lung function for values: FEV1 <80% and FEF25–75% <65%.

The dose of omalizumab administered was calculated based on the patient's weight and levels of circulating IgE, using manufacturers’ specifications.6 In off label patients (total IgE ≥1500KUI/L) the maximum permitted dose according to the patient's weight was used.

Demographic and other baseline data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Wilcoxon test was used to compare the variables at the onset of starting omalizumab with subsequent years for paired data, including visits to emergency department, admissions for exacerbations, mean dose of inhaled fluticasone, and mean FEV1 and FEF25–75%.

McNemar test was used for paired binary samples in patients requiring LABA treatment at baseline and in the following years.

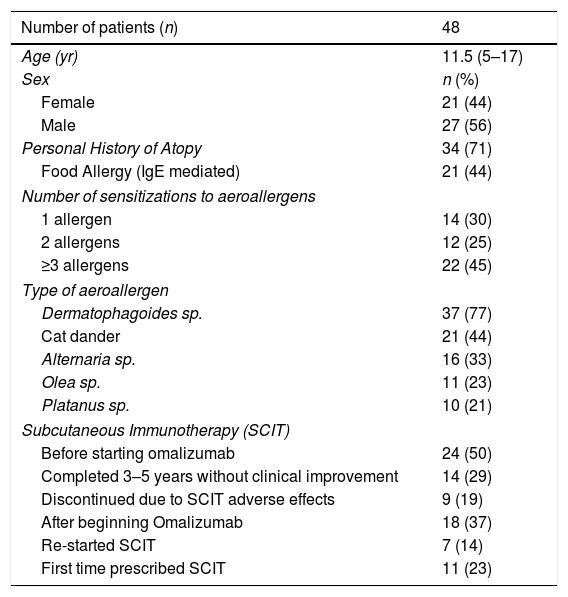

ResultsGeneral and demographic dataWe followed 48 patients, mean age at the beginning of treatment 11.52 years (SD 3.09, range of 5–17 years). Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics.

| Number of patients (n) | 48 |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 11.5 (5–17) |

| Sex | n (%) |

| Female | 21 (44) |

| Male | 27 (56) |

| Personal History of Atopy | 34 (71) |

| Food Allergy (IgE mediated) | 21 (44) |

| Number of sensitizations to aeroallergens | |

| 1 allergen | 14 (30) |

| 2 allergens | 12 (25) |

| ≥3 allergens | 22 (45) |

| Type of aeroallergen | |

| Dermatophagoides sp. | 37 (77) |

| Cat dander | 21 (44) |

| Alternaria sp. | 16 (33) |

| Olea sp. | 11 (23) |

| Platanus sp. | 10 (21) |

| Subcutaneous Immunotherapy (SCIT) | |

| Before starting omalizumab | 24 (50) |

| Completed 3–5 years without clinical improvement | 14 (29) |

| Discontinued due to SCIT adverse effects | 9 (19) |

| After beginning Omalizumab | 18 (37) |

| Re-started SCIT | 7 (14) |

| First time prescribed SCIT | 11 (23) |

n: number of patients. yr: years.

The dose administered ranged from 150–1200mg per month. The frequency of administration was every two weeks in 34 cases and monthly in 14. Fourteen patients were prescribed omalizumab off-label: 13 of them due to total IgE higher than 1500KUI/L and one for being younger than six years old.

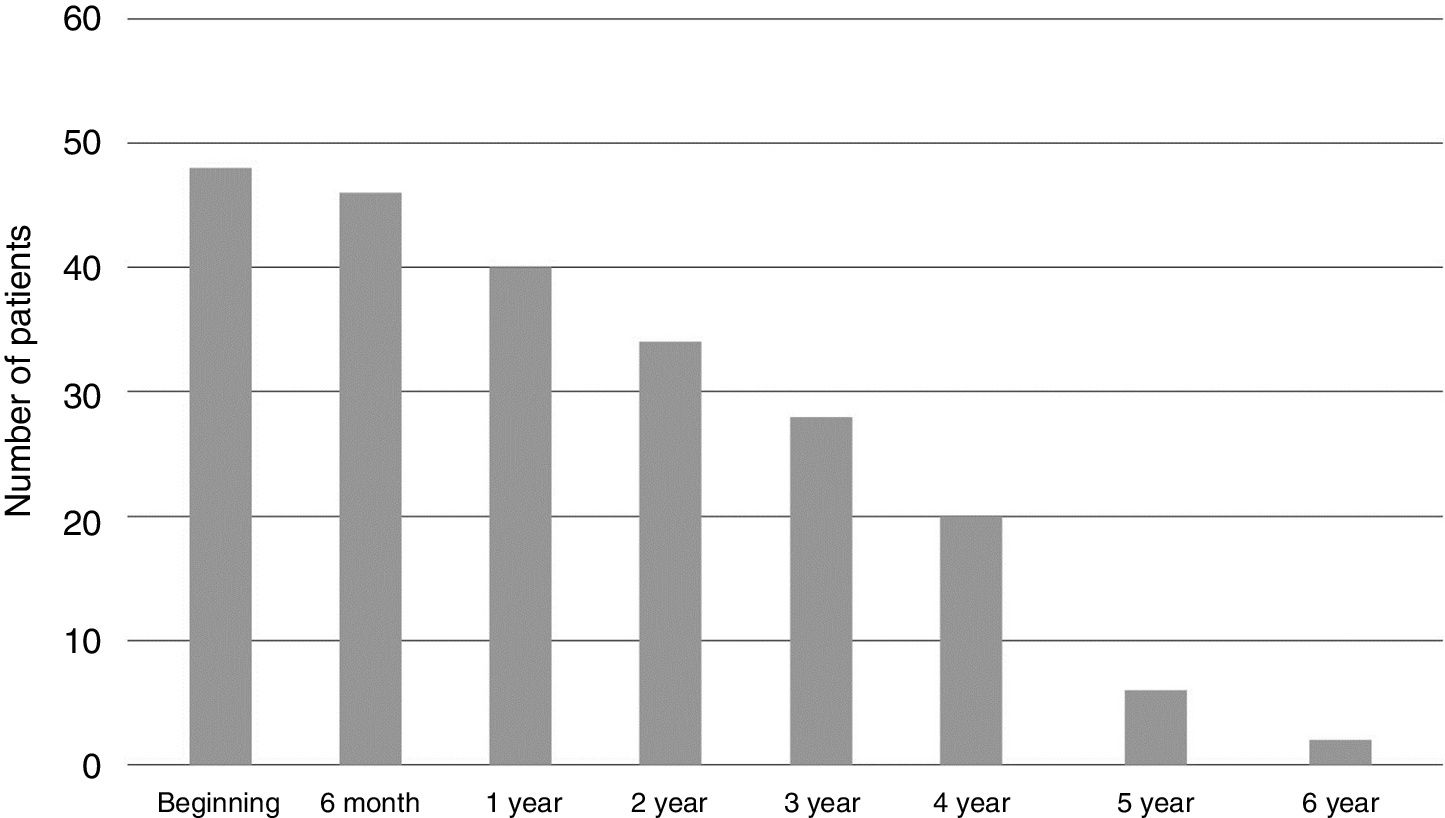

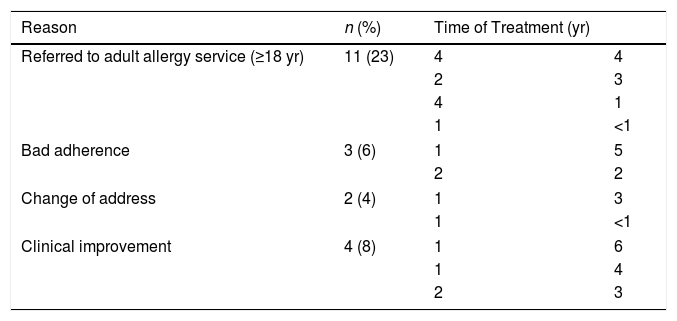

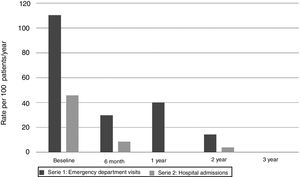

The median follow-up time was 2.9 (0.5–6), with a minimum of six months and a maximum of six years (Fig. 1). During this period 20 patients completed or discontinued treatment with omalizumab (Table 2).

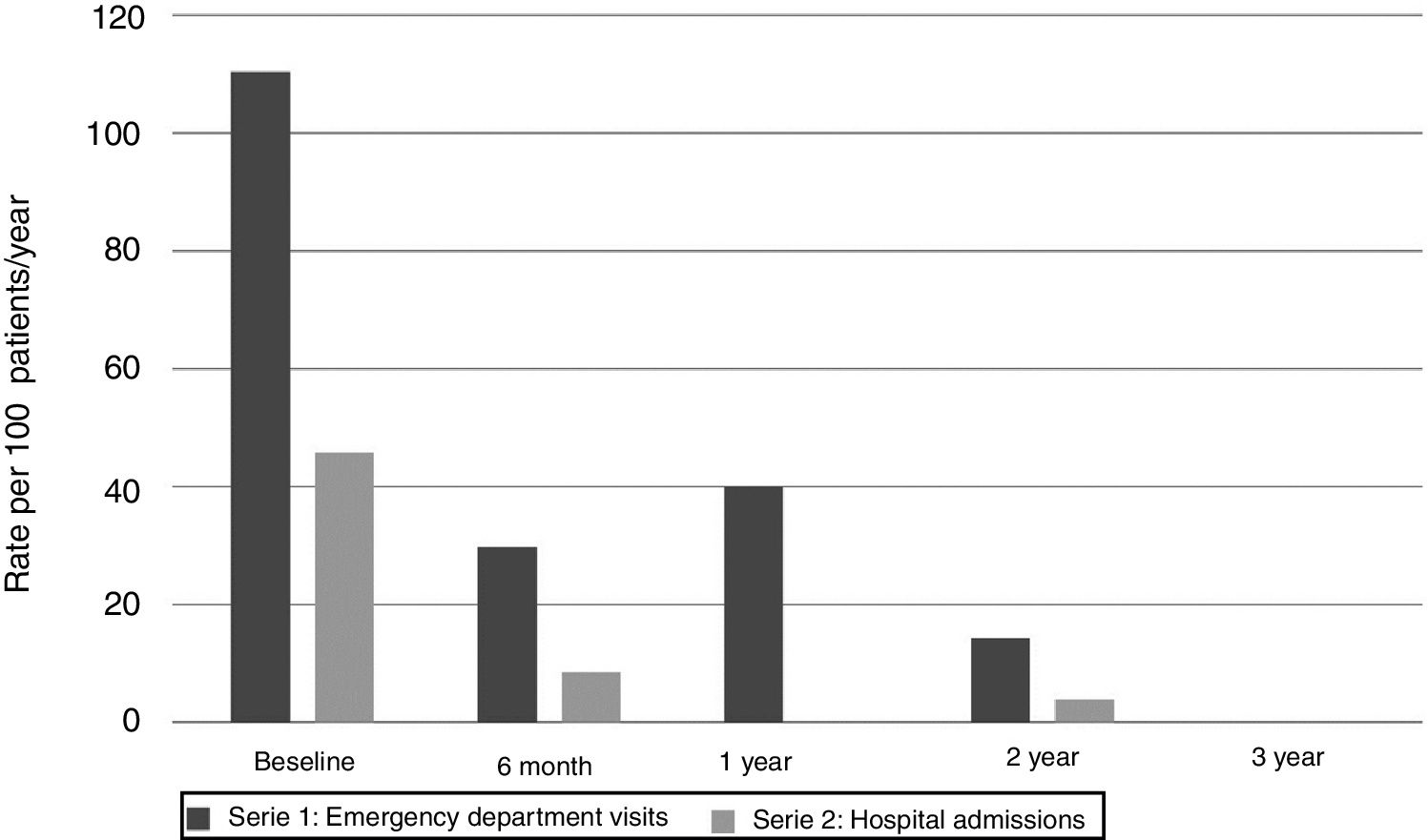

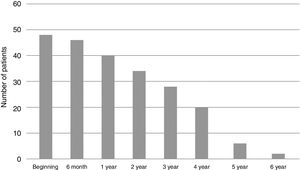

The year before starting omalizumab, 11 patients (23%) required admission for asthma exacerbations, a total of 22 admissions with admission rate per 100patients/year of 45.8. Two patients required admission to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU).

Six months after starting omalizumab this rate decreased to 8.5 per 100patients/year (p=0.02), in the second year the admission rate dropped to 3.9 per 100patients/year (p=0.017). No hospital admissions were recorded after the third year. No PICU hospitalizations were recorded from the start of treatment.

Regarding visits to the emergency department due to asthma exacerbations, during the year prior to starting omalizumab, 24 patients (50%) visited the emergency department, with a total of 53 visits (rate of emergency visits per 100 patients/year 110.41). Six months into treatment the rate dropped to 29.8 per 100 patients/year (p=0.007), and continued to decrease over time, first year 40.0 visits per 100 patients per year (p=0.031), second year 14.3 (p=0.001), none at three years and 10 at four years (p=0.004) (Fig. 2).

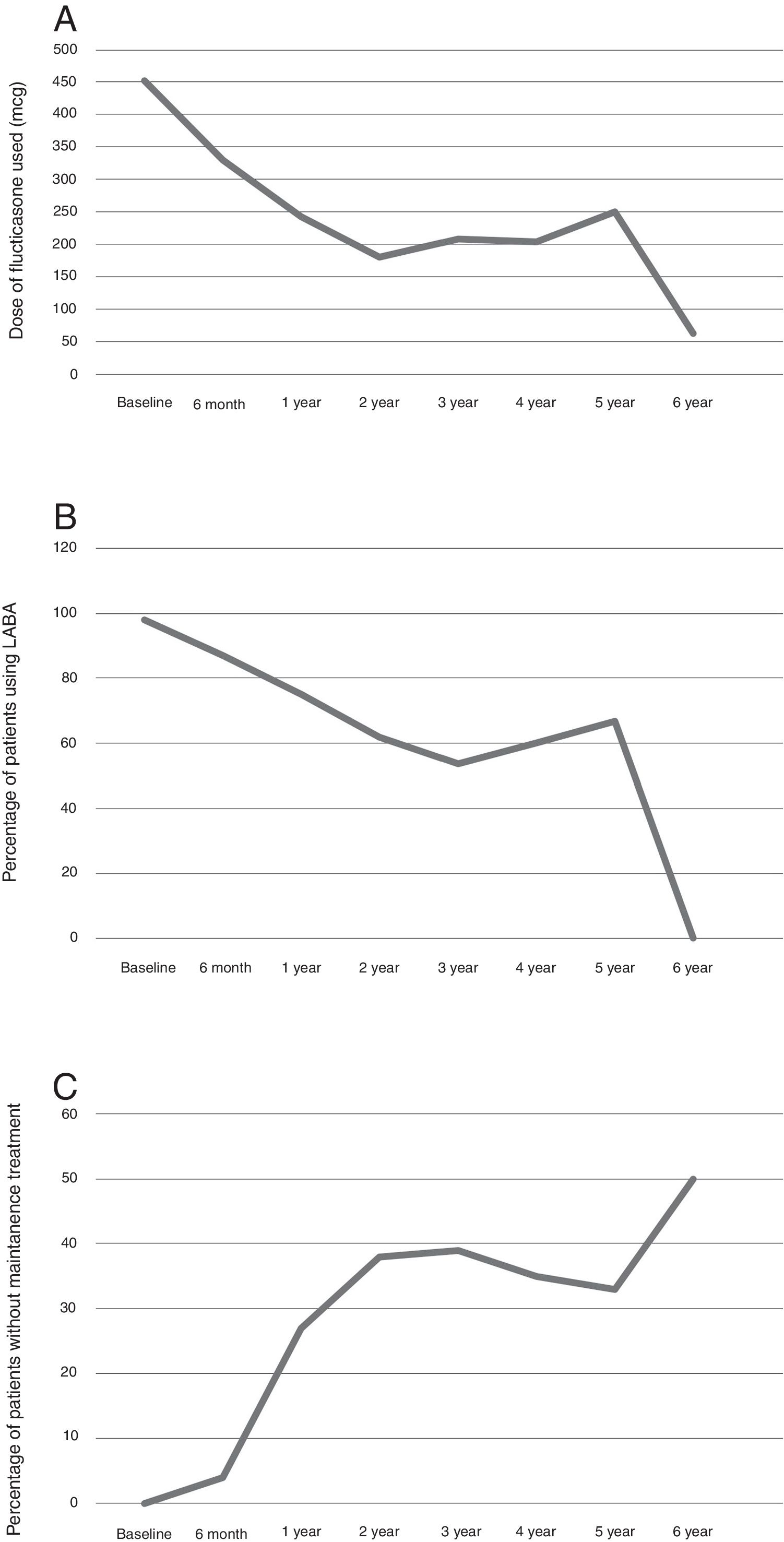

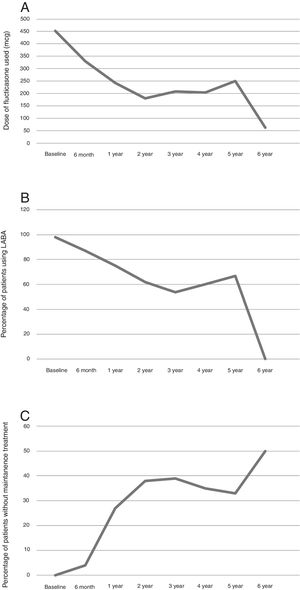

Maintenance treatmentThe mean dose of fluticasone used at the start of treatment with omalizumab was 452mcg/day and at six months 329.89mcg/day (p=0.0001). This difference was maintained through the follow-up (Fig. 3A).

Concerning a long-acting β-2 agonist, at the start of treatment with omalizumab, 98% of the patients required a long-acting β-2 bronchodilator. At six months this lowered to 86.96% (p=0.074), after a year 75% (p=0.008). The difference was maintained through the follow-up (Fig. 3B).

Overall the maintenance therapy used decreased after starting omalizumab (Fig. 3C).

Following initiation of omalizumab, 18 (37.5%) patients were able to start allergen-specific immunotherapy, seven of whom had previously failed to carry on with immunotherapy because of poor asthma control. In these patients no further side effects were seen with the addition of immunotherapy.

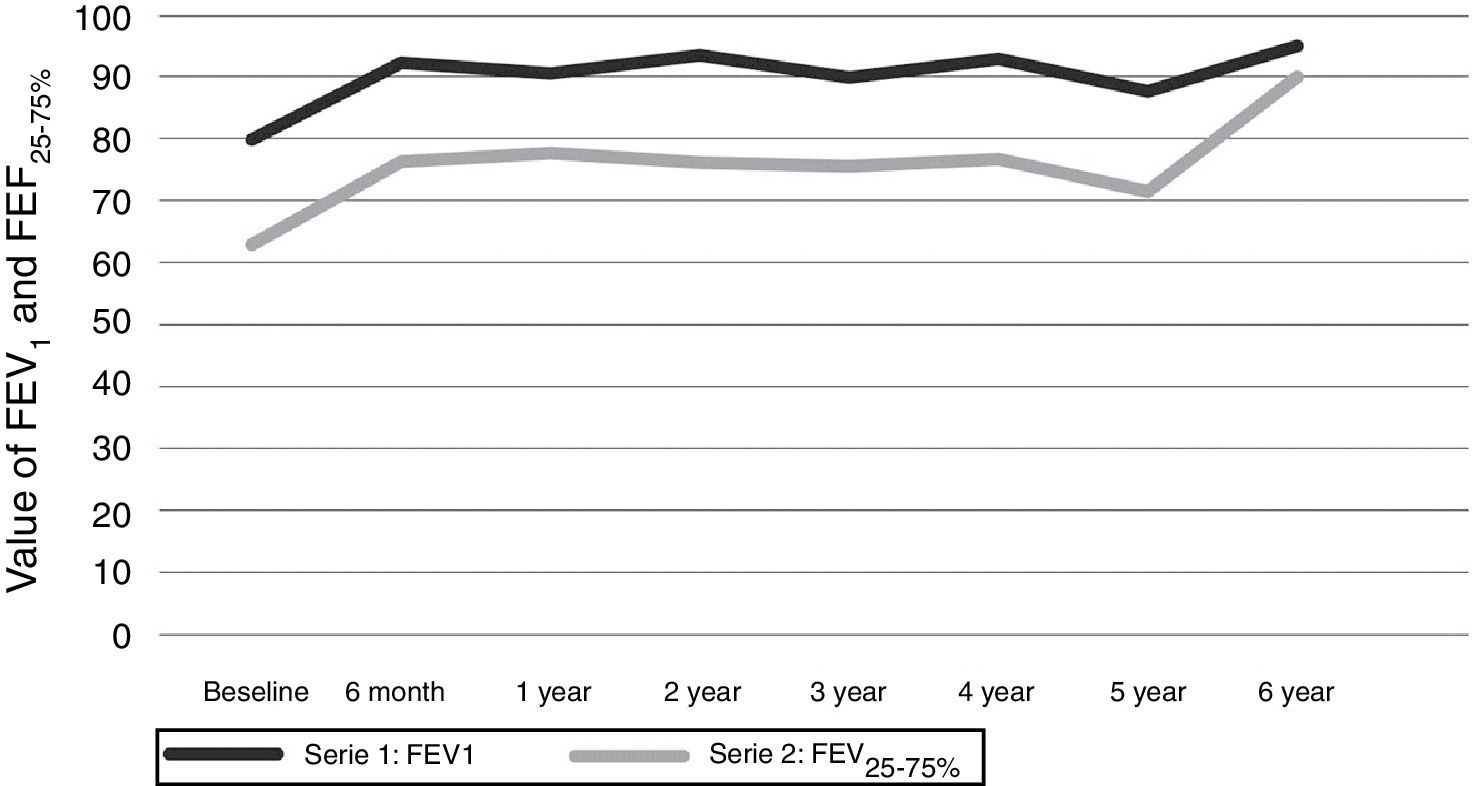

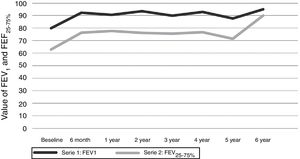

Respiratory functionThe mean values of FEV1 and FEF25–75% at the time of starting omalizumab were 79.88 and 62.94, respectively. After six months of treatment there was an increase in FEV1 to 92.29 and FEF25–75% to 76.31 (p=0.0001). Values were maintained above normal for the course of the treatment (Fig. 4).

Safety outcomesNo adverse effects of omalizumab were seen. All doses were well tolerated and there was no record of local reactions.

DiscussionOur series is the first to publish data on real-life follow-up for six years of children treated with omalizumab for non-controlled asthma, reinforcing that omalizumab can improve asthma stability and lung function in children. After six months of treatment with omalizumab, lung function in children was normalized and remained stable throughout the six years of the study, even when other maintenance therapy decreased. After one year of treatment with omalizumab, visits to the emergency department and hospital admissions were reduced, while maintaining a good safety profile.

Previous ‘real life’ studies in children showed data for shorter periods of timeNoteworthy is that Deschildre et al.19,20 show evolution in 104 patients for one year and 73 up to two years. There is a follow-up for a longer timeframe. Recently Pitrez et al.21 described their experience with omalizumab up to 43 months but in a smaller, 14 patient cohort.

There are few reports in the literature that show an improvement in lung function after initiating treatment with omalizumab. Our study shows improvement in FEV1 and FEF25–75% after only six months of treatment, a change that was maintained through the six-year follow-up. Our results are similar to those published by Deschildre et al.19,20 where an improvement in lung function was recorded in the first year of treatment. Also, an Italian multicenter study of 47 children followed for one year also shows a significant improvement on FEV1.22 These data support the possible benefits of early omalizumab use, to help prevent the lung remodeling process from developing.

However, not all data support changes in spirometry parameters, Pitrez et al.21 did not find change in FEV1 and believe this to be due to a less compromised lung function in children.

In our population, we observed a significant decrease in the number of visits to the emergency department and in hospitalizations due to asthma exacerbations. Furthermore, none of the hospitalizations required intensive care. The first observation is in accordance with data from other randomized controlled trials in children. This benefit is maintained up to the fourth year of treatment. This is reinforced by a systematic review of omalizumab in children in which both randomized and ‘real-life’ studies showed improvement in hospitalization rate and emergency department visits.23

During the first four years of treatment, there was a progressive decrease in additional add-on treatment for asthma control. Other studies have recorded data regarding this, but only for the first year of treatment and mostly regarding inhaled corticosteroids. In our series, patients were classified according to GINA guidelines, and a decrease in the need for LABA and leukotriene inhibitors was found.

Our findings are in accordance with those found in randomized series by Milgrom24 and Busse25 in which a decrease in the need for inhaled corticosteroids was found at 24 and 48 weeks, respectively. Real-life studies in children show a decrease in inhaled corticosteroids which was not statistically significant except in Deschildre's first year cohort.18 Busse also found a decrease in the use of LABA at 48 weeks.24

After six months of treatment, no patients required any oral corticosteroid treatments. Similar to our results, no patients used oral steroids after 16 weeks26 or one year of omalizumab.19

The decrease in maintenance therapy required, specially oral and inhaled steroids at high doses, is of upmost importance in pediatric populations, as long-term side effects in children such as growth impairment are a constant source of concern. The early introduction of Omalizumab could, in the long run, prevent a long period of steroid up-dosing that could prove prejudicial in children.27,28

Another important finding is that 18 patients were able to start specific immunotherapy for aeroallergens which could help them modulate the natural course of their disease. Similar data were published by Stelmach et al.29 regarding 12 patients with severe asthma that were able to start immunotherapy whilst receiving treatment with omalizumab.

The experience with the long-term efficacy of omalizumab in the literature is scarce. A meta-analysis by Rodrigo et al.30 concludes that, in randomized trials, omalizumab has no additional side effects when compared to placebo, 76.3% vs. 74.2%. Real-life experience with omalizumab confirms its safety without finding new or unanticipated adverse effects.31 Our study supports the use of omalizumab in children, as no side-effects were described and good tolerance was reported. However, this is limited by the study design. The three patients that were lost in the follow-up had previously been improving and there is no evidence that they discontinued omalizumab for adverse events.

A limitation is our study follows a ‘real-life’ cohort where normal clinical visits were performed, however patients attended the clinic every 2–4 weeks as omalizumab was administered in our department. Both nurses and pediatricians assessed the child before the dose was given, which meant detailed records were kept.

Another limitation was the different lengths of follow-up and the fact that after four years of treatment the number of patients with omalizumab was low. Our center is exclusively pediatric, and patients are transferred to adult physicians after reaching 18 years of age. Further studies with larger cohorts analyzing the response in the 4- to 6-year window, in children, are needed.

We are continuing our follow-up to answer two key questions: the optimal duration of treatment, and how long the benefit lasts after discontinuing treatment with omalizumab. Up to now, there has been no consensus on when to stop treatment, recommendations suggest an evaluation after 16 weeks, but many experts do not report improvements until after the first year.32

Additional data are also needed in the evolution of patients after stopping omalizumab. The XPORT Multicentric Study discontinued omalizumab after five years and compared the patients free of exacerbations and the time until the first exacerbation in patients continuing omalizumab vs. placebo. Patients that continued with omalizumab were free of exacerbations for a longer period of time.33 Molimard et al.34 showed that for a period of six months after stopping treatment, the benefit was maintained in 45% of their cohort; for children it was 57% but the group only included 14 children. Currently, only limited data are available on children and therefore we intend to undertake the follow-up of our cohort after stopping omalizumab.

ConclusionsOur ‘real-life’ study in children is the longest follow-up to date and confirms the efficacy of omalizumab, with a decrease in the number of exacerbations, reduction of baseline medication, and improvement of lung function. In children this could be attributed to a potential anti-remodeling effect that is not yet properly established. It is important to highlight the safety profile of the long-term use of omalizumab in children and the lack of severe side effects shown in our cohort.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.