Acute urticaria is an immune-inflammatory disease, characterised by acute immune activation. There has been increasing evidence showing that vitamin D deficiency is associated with increased incidence and severity of immune-inflammatory disorders.

ObjectiveThe aim of this study was to evaluate serum vitamin D levels in acute urticaria.

MethodsWe enrolled 30 children with acute urticaria and 30 control subjects. Concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], a biomarker of vitamin D status, were measured in serum of acute urticaria patients and compared with the control group.

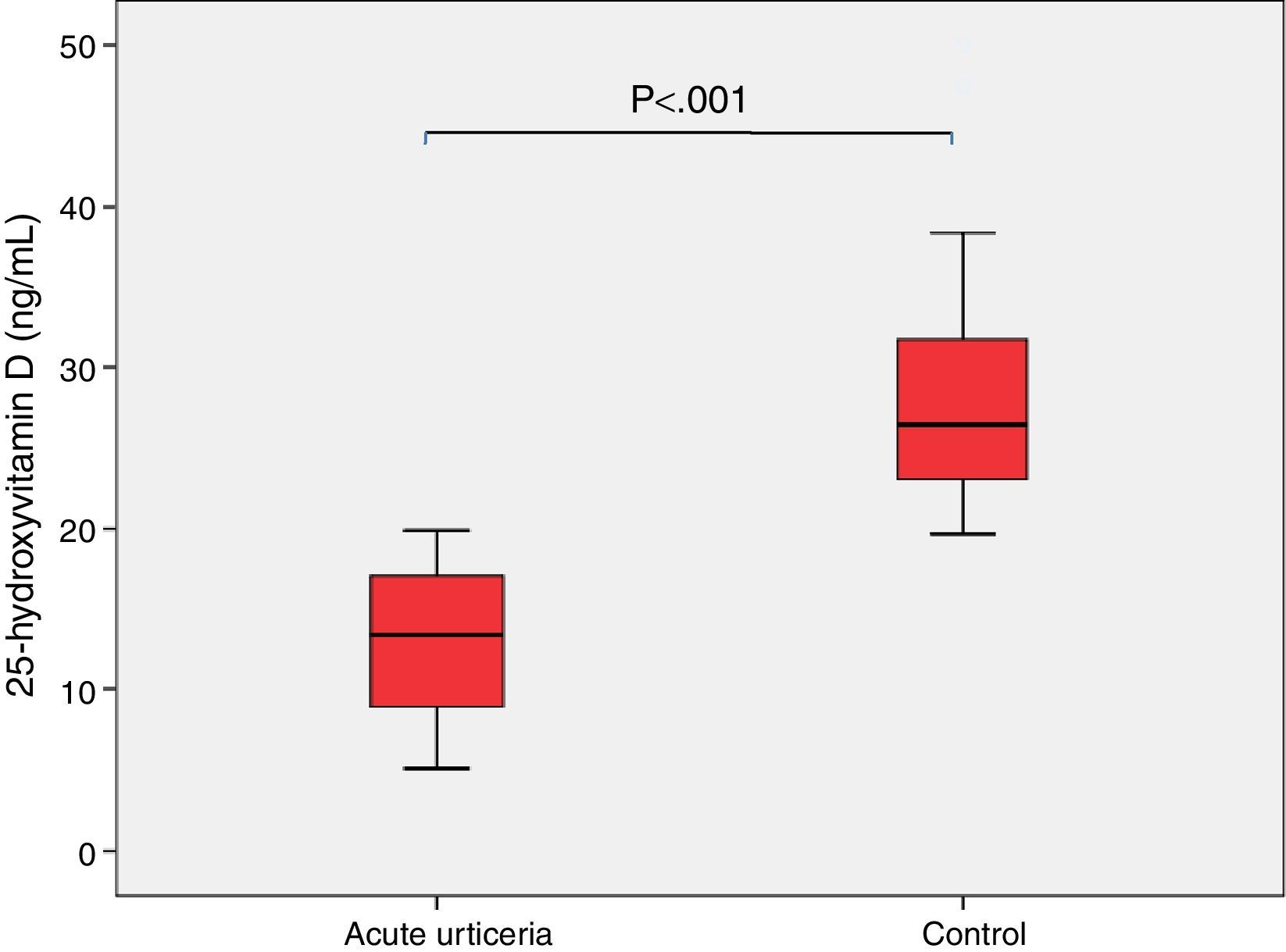

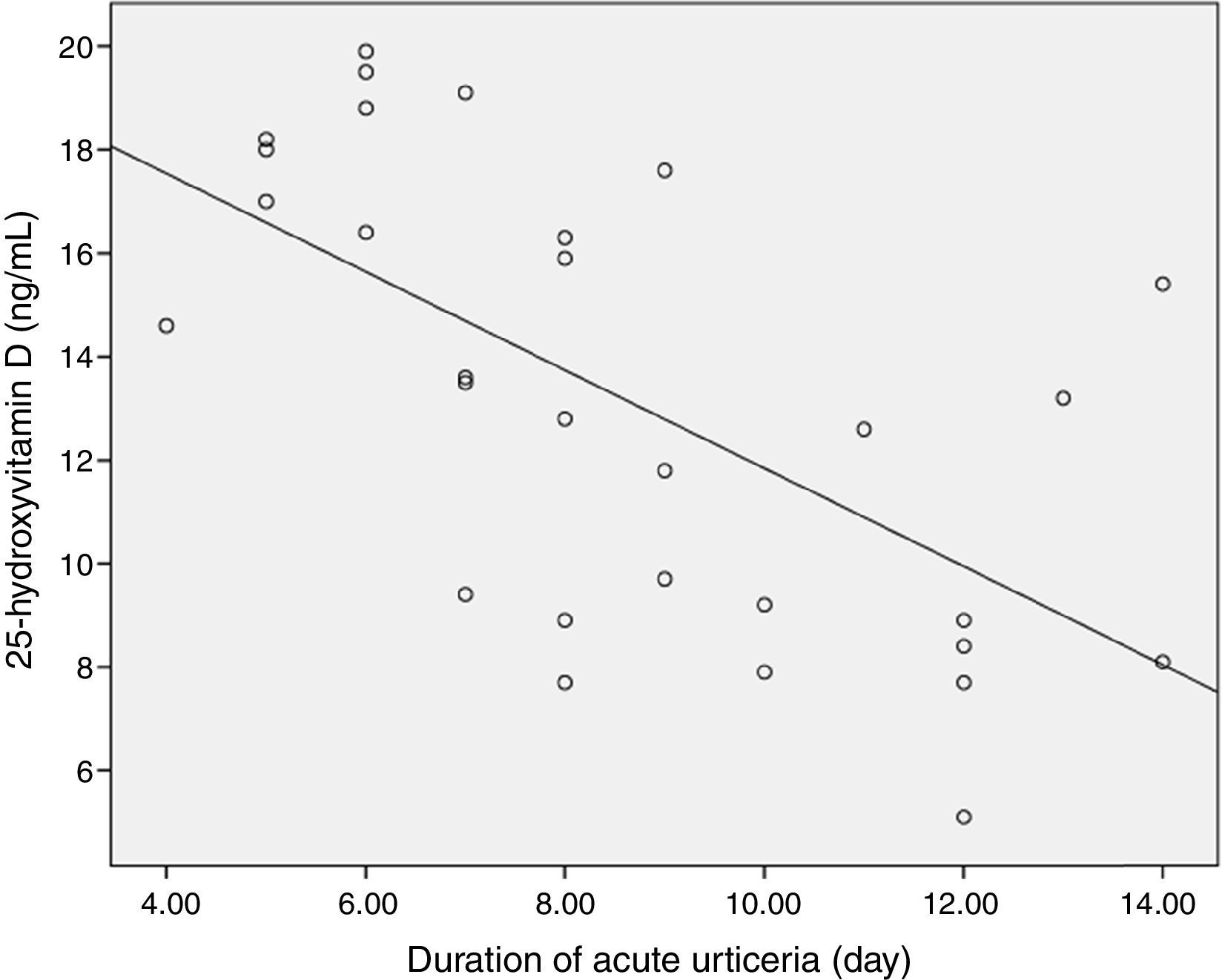

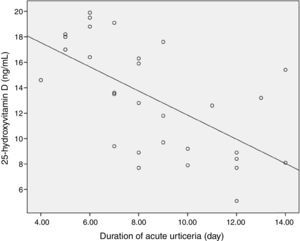

ResultsThere were no significant differences in baseline variables (age, gender, weight) between the groups. Vitamin D deficiency (<20ng/ml) was significantly higher in patients with acute urticaria than in control patients. Serum 25(OH)D levels were significantly lower in the study group compared to those in the control group (13.1±4.3 vs 28.2±7.4ng/mL, p<0.05). Moreover, we found negative correlation between mean duration of acute urticaria and serum vitamin D levels (p<0.01).

ConclusionThis study revealed a significant association of lower serum 25(OH)D concentrations with acute urticaria and an inverse relationship with disease duration. These findings may open up the possibility of the clinical use of vitamin D as a contributing factor in the pathogenesis of acute urticaria and a predictive marker for disease activity in acute urticaria. A potential role of vitamin D in pathogenesis and additive therapy in acute urticaria needs to be examined.

Acute urticaria is an inflammatory disease, characterised by itchy, short lived, and elevated erythematous wheals anywhere on the skin. The reaction triggers an acute phase response and immune activation associated with the release of mediators from cutaneous mast cells and basophils.1 The release of mast cell derived mediators may be caused by both immune and non-immune mechanisms.1 Acute urticaria is defined when the symptoms happen for less than six weeks and is considered to be recurrent acute if the duration of symptom free periods between urticaria episodes is longer than six weeks.2 Although a specific cause is not frequently identified, the onset of acute urticaria has been associated with allergic reactions to foods and drugs, contact with chemicals, physical stimuli or infections.1,2

Degranulation of cutaneous mast cells by a variety of causes results in the release of histamine and other inflammatory mediators which initiate local or generalised skin involvement in patients with acute urticaria.1 Mast cells, dendritic cells, monocytes, neutrophils and cytokines have been implicated in the pathogenesis of acute urticaria.2

Vitamin D affects both innate and adaptive immune mechanisms. It plays an important role in the immune response generated by lymphocytes and antigen presenting cells. Mast cells and eosinophils are vitamin D targets. Vitamin D also affects B lymphocyte functions and modulates the humoral immune response as well as secretion of IgE.3,4 Its role on the regulation of the immune system cells has been recognised recently with the detection of Vitamin D receptors (VDRs). These receptors have been identified on nearly all immune system cells including T cells, B cells, neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells.4 Vitamin D also affects the innate immune system by stimulating the production of cathelicidin, which is an anti-microbial peptide that is activated through toll-like receptors, increasing pro-inflammatory cytokine production.5

It has been noted that in children, low serum 25(OH)D levels are associated with increased risks for allergic diseases.6–8 Vitamin D contributes to the conversion of CD4+ T cells to T regulatory cells, which have been shown to play an important role in the suppression of pro-allergic mechanisms, thereby defining the possible association of vitamin D to allergic disorders.9

Since vitamin D is mostly absorbed all over the skin, the effect of vitamin D levels on skin diseases is of particular interest. Most of the studies assess the impact of vitamin D on skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis (AD).10 These studies supported that vitamin D deficiency may be tied to skin diseases, including AD. However, a few studies evaluated the potential link between vitamin D and chronic urticaria.11,12 Therefore, the relationship between acute urticaria and vitamin D is still under debate.

Based on such reports, it seems reasonable to suspect that vitamin D may also play a role in the pathomechanism of acute urticaria. However, limited data is available on the vitamin D status of patients with acute urticaria. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between serum vitamin D status and acute urticaria in children.

Materials and methodsStudy subjectsWe enrolled 60 children [30 children with acute urticaria (study group) and 30 children with no symptoms or signs of allergic diseases (control group)] who admitted to our outpatient clinics from May to August 2015. Patients were diagnosed with acute urticaria by the appearance of circumscribed, slightly elevated, erythematous, oedematous papules or wheals due to any aetiology attending the consultation. Lesions varied from moment to moment, disappeared within minutes or hours and lasted <24h.2 The study population was composed of patients diagnosed with acute urticaria with a clinical history of symptoms for less than six weeks.2 Subjects with significant medical history of low 25(OH)D levels, those who had taken vitamin D supplements last one year, those with urticarial vasculitis, atopic dermatitis, defined dermatoses and patients with chronic diseases affecting vitamin D levels were excluded. Children who were healthy were selected as controls. The study conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent was obtained from the parents. The study was approved by Baskent University Institutional Review Board (Project no: KA15/263).

Study designAll patients had a physical examination after obtaining their history including time of onset of disease, frequency, duration, size and distribution of wheals, associated angio-oedema, family history of urticaria and atopy, previous or current allergies, infections, use of drugs, correlation to food, breastfeeding history, prophylactic vitamin D supplementation during infancy and duration of exposure to sunlight in a week. Vitamin D content in diet was similar in all patients.

Complete blood counts, percentage of eosinophils, and 25(OH)D levels were measured in each case. Venous blood samples were drawn and sera were stored at −20°C after centrifugation until testing. All assays were carried out at the same time. Complete blood count collected in tubes that contains K3EDTA were analysed by means of a haemocytometer (Abbott Cell-Dyn Ruby System, Abbott Diagnostics, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

The levels of 25(OH)D were assayed using chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (Abbott Architect I2000 analyser). The Archıtect 25-OH Vitamin D assay is designed to have a Limit of Detection (LoD) of ≤10.0ng/mL. Serum 25(OH)D levels above 30ng/mL were regarded as sufficiency, 20–29ng/mL as vitamin D insufficiency, <20ng/mL as vitamin D deficiency, and <10ng/mL as critically low vitamin D deficiency.13,14

Statistical analysisThe results of tests were expressed as the number of observations (n), mean±standard deviation, median and min–max values. Homogeneity (Levene's Test) and normality tests (Shapiro–Wilk) were used to decide which statistical methods to apply in the comparison of the study groups. Comparison between the two groups in terms of measured variables was performed by using Student's t-test and comparison of categorical variables using the Chi square test on SPSS software (SPSS Ver. 17.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago IL, USA). p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

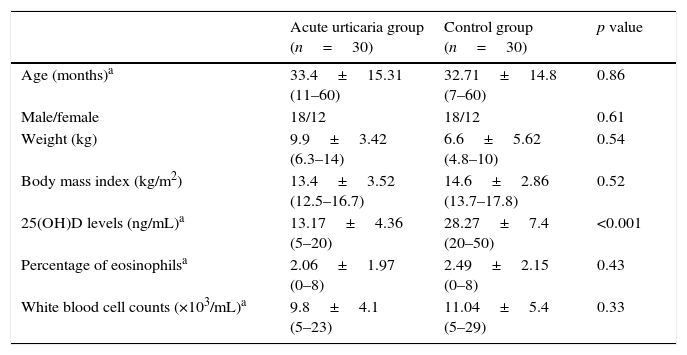

ResultsThe clinical characteristics of the study subjects are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in the baseline variables (age, gender, weight, body mass index) between the groups. Duration of exclusive breastfeeding and prophylactic vitamin D supplementation during infancy, allergy history and family history of allergic diseases (bronchiolitis, asthma, allergic rhinitis and wheezing) were similar between study and control groups. Mean (SD) hours of sunlight exposure per week [7.1 (9.4) vs. 9.3 (13.4)] were similar between the cases and controls, respectively. Duration of prophylactic Vitamin D supplementation during infancy was 10.71±2.01 (6–15 months) in acute urticaria group and 11.47±3.1 (4–18 months) in control group (p=0.28). Duration of breastfeeding was 7.71±3.21 (3–15 months) in acute urticaria group and 8.83±3.9 (3–24 months) in control group (p=0.24). There were no significant differences in allergic history (n, %, acute urticaria group, 17, 56.7%, vs. controls, 13, 43.3%) (p=0.30) and family history of allergic diseases (acute urticaria group, 20, 66.7%, vs. controls, 13, 43.3%) (p=0.07) between the groups.

Clinical characteristics and laboratory parameters of the study subjects.

| Acute urticaria group (n=30) | Control group (n=30) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months)a | 33.4±15.31 (11–60) | 32.71±14.8 (7–60) | 0.86 |

| Male/female | 18/12 | 18/12 | 0.61 |

| Weight (kg) | 9.9±3.42 (6.3–14) | 6.6±5.62 (4.8–10) | 0.54 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 13.4±3.52 (12.5–16.7) | 14.6±2.86 (13.7–17.8) | 0.52 |

| 25(OH)D levels (ng/mL)a | 13.17±4.36 (5–20) | 28.27±7.4 (20–50) | <0.001 |

| Percentage of eosinophilsa | 2.06±1.97 (0–8) | 2.49±2.15 (0–8) | 0.43 |

| White blood cell counts (×103/mL)a | 9.8±4.1 (5–23) | 11.04±5.4 (5–29) | 0.33 |

There were no significant differences in percentage of serum eosinophils and white blood cell counts between study and control groups (Table 1). Serum 25(OH)D levels were significantly lower in the study group compared to those in control group (13.1±4.3 vs. 28.2±7.4ng/mL, p<0.05) (Fig. 1).

Mean duration of acute urticaria was 8.6±2.8 days (range: 4–14 days). A negative correlation was found between the mean duration of acute urticaria and serum vitamin D levels (Spearman's rho: −0.68, p<0.01) (Fig. 2). Seventeen (56.7%) of the patients in the study group had history of allergy. An infection was diagnosed in eight patients (26.6%) who had acute urticaria. Four patients had lower respiratory tract infection, two patients had upper respiratory tract infection, and two patients had urinary tract infection. Allergic reactions to antibiotic in 10 (33.3%) and to cow's milk in four (13.3%) of patients were diagnosed. Also a specific cause was not identified in eight (26.6%) acute urticaria patients. In patients with low serum vitamin D levels (<20ng/ml), vitamin D therapy was administered in addition to conventional treatment for the acute urticaria.

DiscussionVitamin D is known to play an important role in the regulation of immune system.3 Studies indicate that vitamin D deficiency may contribute to increased risk of atopic dermatitis and chronic urticaria.11,12 However, studies are limited in identifying the relationship between serum 25(OH)D levels and acute urticaria in children. The aim of our study was to determine whether serum 25(OH)D levels were related with acute urticaria. This is the first study evaluating vitamin D levels in children with acute urticaria and we found that 25(OH)D levels were lower in these patients.

Several studies have analysed the relationship between serum 25(OH)D levels and allergic diseases in children7–9,18 and suggested that vitamin D deficiency contributes to the development of atopic dermatitis.7,18 A study by Oren et al.10 showed that there was an increased risk of AD among vitamin D deficient patients. Cheon et al.18 reported that serum 25(OH)D levels were lower in patients with atopic dermatitis, and considerably decreased in the moderate and severe cases. Vitamin D contributes to the conversion of CD4+ T cells to T regulatory cells, which have been an important role in the suppression of pro-allergic mechanism and may play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis through enhancing the integrity of the permeability barrier, antimicrobial peptide expression and suppressing inflammatory responses.6,15

As compared to AD, there are fewer studies that have evaluated the relationship between vitamin D and urticaria. Throp et al.11 reported that serum vitamin D levels were significantly reduced in patients with chronic urticaria as compared to controls (29 vs. 40ng/ml). Another study demonstrated that the incidence of low 25(OH)D levels was high in adults with chronic urticaria.19 Those studies indicate that patients with chronic urticaria may be associated with lower vitamin D concentrations in adults during the active period of the disease.11,19 Vitamin D deficiency also has been shown to be implicated in drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) recently.16,17 Our results are consistent with reported studies about the relationship between vitamin D and chronic urticaria, atopic dermatitis or DRESS.7,11,12,16–18

As vitamin D is considered as a marker for the acute phase of inflammation, it could be suspected that low vitamin D levels may provide presenting acute urticaria. In our study, we found that serum vitamin D levels in patients with acute urticaria were lower compared to those in the control group. Vitamin D receptors bind to target genes to moderate gene expression in dendritic cells, macrophages and other antigen presenting cells and Vitamin D has anti-inflammatory properties, as observed by the reduction of dendritic cell maturation and inhibits dendritic cell migration, IL-12 and IL-23 cytokine production.5 Vitamin D also has a role in the suppression of pro-allergic mechanism by conversion of CD4+ T cells to T regulatory cells and has a beneficial effect in maintaining the permeability barrier in the epidermis. Allergy mediating cells such as mast cells and eosinophils are vitamin D target cells. Mast cells, dendritic cells, monocytes, neutrophils and cytokines have been implicated in the pathogenesis of acute urticaria. Increased vitamin D synthesis increases IL-10 production in mast cells, which leads to suppression of skin inflammation.5 This may cause one of the reasons of acute urticaria. Since Vitamin D is an important factor in the regulation of the innate immune system, has anti-inflammatory properties, has a role in the suppression of pro-allergic mechanism by conversion of CD4+ T cells to T regulatory cells and has a beneficial effect in maintaining the permeability barrier in the epidermis, we think that low Vitamin D levels may cause susceptibility to acute urticaria and may lead to longer duration of symptoms. The exact mechanism of the relationship between vitamin D deficiency and acute urticaria is thus far not clear, we suspect that besides the direct action of vitamin D, its modulatory function on various inflammatory cells might partially explain the association of vitamin D deficiency with acute urticaria.

Acute urticaria is a common skin disease. Antihistamines are the first line treatments and systemic steroids are used if needed.20 Current data demonstrate the importance of screening for vitamin D deficiency in chronic urticaria patients. Studies have demonstrated that resolution of the symptoms is often possible with oral supplementation of vitamin D in patients suffering from idiopathic chronic urticaria, isolated pruritus, and rash with low 25(OH)D levels.12,21 Goetz et al.12 investigated the possible therapeutic effect of vitamin D for idiopathic itch, rash, and urticaria symptoms in adults. Similar to our study, they showed that serum 25(OH)D levels were significantly lower in those patients.12 Further research is needed to establish the benefit of using vitamin D to treat patients with acute urticaria and low vitamin D status in addition to conventional treatments.

In conclusion, low serum 25(OH)D levels were found in children with acute urticaria. We believe that this study may provide potential pathways for future research on understanding the role of vitamin D in acute urticaria. Furthermore, vitamin D supplementation might be used to improve the symptoms of those with acute urticaria, or to provide benefits as an add-on therapy in the treatment of acute urticaria.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Conflict of interestAll authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The study was approved by Baskent University Institutional Review Board (Project no: KA15/263).