To examine sleep patterns and sleep disturbance of children with food allergy (FA) and their mothers.

MethodsThe food allergy group included 71 children with mean age, 2.97±1.52 years, and 58 control children were recruited the study. Mothers of children completed the Childhood Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) and The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) in order to evaluate sleep disturbance in both children and themselves. Depressive symptomatology of mothers of children with or without food allergy was assessed with Beck-Depression Inventory II (BDI-II).

ResultsThe mean total scores of CSHQ was 49.33±7.93 (range=31–68) in the FA and 42.39±6.43 (range=30–62) in controls. The total CSHQ scores were significantly higher in children with FA than in controls (p=0.002). The total PSQI score was significantly higher in mothers of children with FA than in mothers of children without FA (7.09±3.11 vs 5.15±2.59, p<0.001) indicating that the mothers of children with FA had worse sleep quality. The mothers of children with FA had more depressive symptoms than mothers of children without FA. The mean total scores of BDI-II were 10.10±6.95 in mothers of children with FA and 7.78±6.64 in mothers of children without FA (p=0.005).

ConclusionThe presence of a food allergy in a child may be associated with a deterioration in sleep quality in children and mothers as well as increased depressive symptoms in mothers.

Food allergy (FA) is a growing public health problem throughout the world that affects the daily lives of children and their caregivers in varying degrees.1,2 There are currently no cures available for patients with food allergy. Therapy is focused on food avoidance and emergency treatment of accidental food allergen ingestion.3

Sleep disorders are the most common behavioral problems in children. Sleep patterns change throughout life, although the quality and quantity of sleep always depend on individual factors such as age, sex, and psychological and environmental factors.4 Asthma and/or allergic rhinitis have been associated with sleep disturbances. Children with respiratory and atopic disease demonstrate poorer sleep than healthy children.5 Recent studies on the relationship between food allergies and sleep disorders have increased. Wang et al.6 reported a close relationship between food allergy and snoring in Chinese infants. A recent study reported that children with gastrointestinal (GI) food allergy were commonly associated with a wide range of extra-intestinal manifestations, such as poor sleep.7 In another study investigating sleep disorders in allergic and non-allergic children, eczema and food allergies were closely associated with sleep disorders.8

The presence of a child with food allergy in the family adversely affects the quality of life of the parents. As the number of children with allergies increases, quality of life is negatively affected both by the parent’s time for their own needs and in terms of family activities.9 When mothers and fathers were compared, mothers perceived their quality of life as worse and had higher anxiety levels.10

It is necessary to periodically evaluate children with food allergy and primary caregivers in terms of the need for psychosocial support. The purpose of this study was to compare sleep in young children with and without FA and their mothers. Additionally, the depressive symptomatology of the mothers was assessed. We hypothesized that compared with young children without FA, young children with FA would have poorer sleep patterns. We also aimed to investigate the sociodemographic and clinical correlated factors of sleep disturbances in these groups

Materials and methodsParticipantsChildren between two and 10 years, followed up for FA for at least one month at the Pediatric Allergy and Gastroenterology Departments in our clinics, between June 2017 and February 2019 were enrolled. Diagnosis of FA was made for patients who fulfilled all of the following criteria: 1) food sIgE level ≥0.35kU/L and/or a positive skin prick test with food (a wheal ≥3mm compared with the negative control); 2) consistent and clear-cut history of the repeated symptoms associated with both IgE-related and non-IgE-mediated reaction upon the food allergen exposure; and 3) positive oral food challenge. Children with chronic illness or severe/uncontrolled allergic disease were excluded. The Ethics Committee of our hospital approved the study, and written informed consent was given by the parents or legal guardians of the patients.

The clinical and laboratory characteristics of patients and the sociodemographics of parents were recorded. Information about the number and type of food allergies, previous allergic reactions and medications given was obtained from the parents.

MaterialsSociodemographic data formCharacteristics of children (age, gender, comorbid medical disorder, duration of the food allergy, family history of atopy), sociodemographic characteristics of the family (family income, number of family members, education level of mother who the child was interviewed with) and existence of psychiatric disorder history in the family were assessed by a sociodemographic form that was developed by the authors.

Childhood sleep habits questionnaire (CSHQ)The CSHQ11 is a retrospective, 45-item sleep-screening instrument designed for young children based on the parent report and is also used in both toddlers and adolescents.12

The CSHQ total and subscale scores significantly differentiated the clinical sample from the community sample using 33 of the items. Hence the CSHQ with 33 items gives the total score and eight subscale scores: bedtime resistance; sleep-onset delay; sleep duration; sleep anxiety; nightwaking; parasomnias; daytime sleepiness; and sleep disordered breathing.

Items in the questionnaire rate on a three-point Likert scale (one for rarely (0–1 night per week); two for sometimes (2–4 nights per week); three for usually (5–7 nights per week)). The total CSHQ score of 41 has been reported to be a sensitive clinical cut-off for the identification of probable sleep problems. Turkish validation and reliability was carried out by Fis et al.13 The questionnaire was filled out by the authors of this study through interviewing the child’s parent.

The Pittsburgh sleep quality indexThe Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)14 was used to assess the mother’s sleep quality and sleep disturbance in the last month. The PSQI is a questionnaire assessing sleep quality as well as the presence and severity of sleep disorders in adults. It includes seven components and 19 self-rated questions assessing subjective sleep quality; sleep latency; sleep duration; habitual sleep efficiency; sleep disturbances; use of sleep medications; and daytime dysfunction. All questions are rated between 0 and 3 points: 0, not during past month; 1, less than once a week; 2, once or twice a week; 3, three or more times a week. In addition, sleep quality is rated as follows: 0, very good; 1, fairly good; 2, fairly bad, 3 very bad. Component scores are summed to obtain a global score ranging between 0–21 points. Higher global scores indicate worse sleep quality. Turkish validation and reliability study was performed by Agargun et al.15 The PSQI provides a global score, with higher scores indicating poorer sleep quality, and a total score >5 indicative of significant sleep disruption.

Beck depression inventory II (BDI-II)Depressive symptomatology of the mothers was measured with the BDI-II,16 a 21-item self-report instrument. Items on the BDI-II are rated on four-point scales ranging from zero to three, with a maximum total score of 63. Higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms. The validity and reliability study of the scale was conducted by Kapcı et al.17 Total score 0–12 shows minimal depression; 13–18 shows mild depression; 19–28 shows moderate depression; and 29–63 shows severe depression.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis were performed by using SPSS 22.0 software (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to define demographic and clinical variables of all participants. Categorical variables were compared with chi-square test. The normality of the data distributions was checked with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. According to the results, an independent t-test or a Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables between groups. To analyze the correlations between duration of illness, total IgE, CSHQ, PSQI and Beck Depression scores, Pearson’s correlation test were used. Binary logistic regression analysis were performed to determine variables that predicted sleep disorder. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

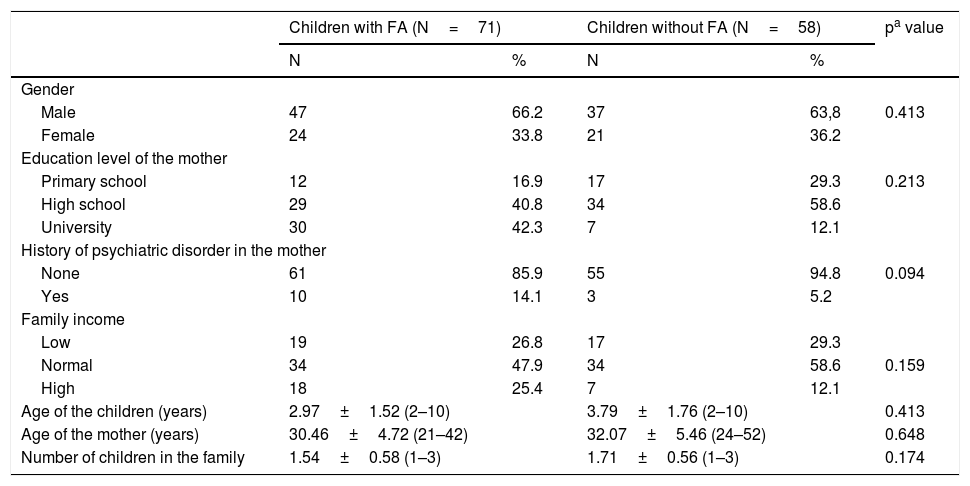

ResultsSociodemographic characteristics of the participantsA total of 71 children with FA and 58 control children with a mean age of 3.34±1.68 years were recruited to the study. There were no statistically significant differences between groups in term of the gender, age of the children, age of the mothers, number of children the family has, mental illness history in the family, family income and the education level of the mother (Table 1). The clinical and laboratory characteristics of the food allergy group are given in Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants.

| Children with FA (N=71) | Children without FA (N=58) | pa value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 47 | 66.2 | 37 | 63,8 | 0.413 |

| Female | 24 | 33.8 | 21 | 36.2 | |

| Education level of the mother | |||||

| Primary school | 12 | 16.9 | 17 | 29.3 | 0.213 |

| High school | 29 | 40.8 | 34 | 58.6 | |

| University | 30 | 42.3 | 7 | 12.1 | |

| History of psychiatric disorder in the mother | |||||

| None | 61 | 85.9 | 55 | 94.8 | 0.094 |

| Yes | 10 | 14.1 | 3 | 5.2 | |

| Family income | |||||

| Low | 19 | 26.8 | 17 | 29.3 | |

| Normal | 34 | 47.9 | 34 | 58.6 | 0.159 |

| High | 18 | 25.4 | 7 | 12.1 | |

| Age of the children (years) | 2.97±1.52 (2–10) | 3.79±1.76 (2–10) | 0.413 | ||

| Age of the mother (years) | 30.46±4.72 (21–42) | 32.07±5.46 (24–52) | 0.648 | ||

| Number of children in the family | 1.54±0.58 (1–3) | 1.71±0.56 (1–3) | 0.174 | ||

FA: food allergy, values are presented as number (%) or mean (interquartile range), bold represents the significant p-values: p<0.005.

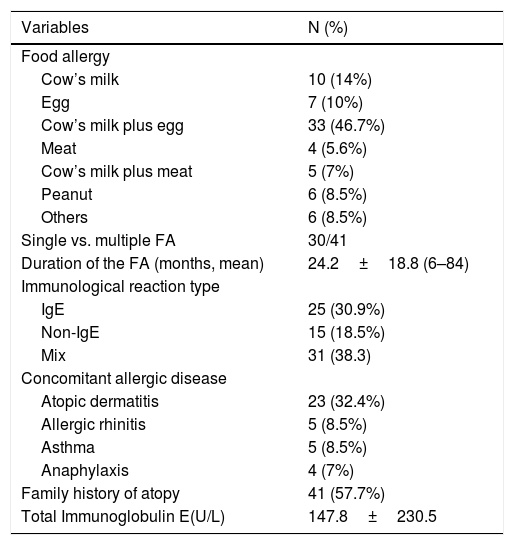

Clinical and laboratory characteristics of patients with food allergy.

| Variables | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Food allergy | |

| Cow’s milk | 10 (14%) |

| Egg | 7 (10%) |

| Cow’s milk plus egg | 33 (46.7%) |

| Meat | 4 (5.6%) |

| Cow’s milk plus meat | 5 (7%) |

| Peanut | 6 (8.5%) |

| Others | 6 (8.5%) |

| Single vs. multiple FA | 30/41 |

| Duration of the FA (months, mean) | 24.2±18.8 (6–84) |

| Immunological reaction type | |

| IgE | 25 (30.9%) |

| Non-IgE | 15 (18.5%) |

| Mix | 31 (38.3) |

| Concomitant allergic disease | |

| Atopic dermatitis | 23 (32.4%) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 5 (8.5%) |

| Asthma | 5 (8.5%) |

| Anaphylaxis | 4 (7%) |

| Family history of atopy | 41 (57.7%) |

| Total Immunoglobulin E(U/L) | 147.8±230.5 |

FA: food allergy; others: tuna fish (2), salmon, wheat (2), soy.

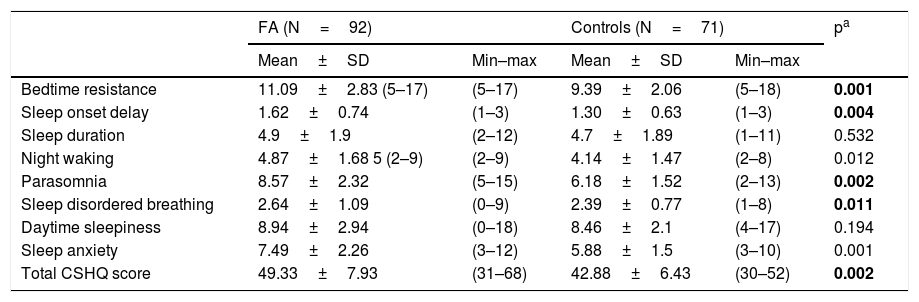

Of the children with FA 83.4%, with controls 50% of them were found to have a sleep problem according to the CSHQ. The mean total scores of CSHQ was 49.33±7.93 (range=31–68) in the FA and 42.39±6.43 (range=30–62) in the controls. The difference in total CSHQ scores between the two groups was statistically significant (Mann Whitney U, p=0.002). The total CSHQ scores were significantly higher in children with FA than controls. Table 3 summarizes the CSHQ total scale score and the subscales scores of patients and controls.

Comparison of total and subscale of the CHSQ between the groups.

| FA (N=92) | Controls (N=71) | pa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | Min–max | Mean±SD | Min–max | ||

| Bedtime resistance | 11.09±2.83 (5–17) | (5–17) | 9.39±2.06 | (5–18) | 0.001 |

| Sleep onset delay | 1.62±0.74 | (1–3) | 1.30±0.63 | (1–3) | 0.004 |

| Sleep duration | 4.9±1.9 | (2–12) | 4.7±1.89 | (1–11) | 0.532 |

| Night waking | 4.87±1.68 5 (2–9) | (2–9) | 4.14±1.47 | (2–8) | 0.012 |

| Parasomnia | 8.57±2.32 | (5–15) | 6.18±1.52 | (2–13) | 0.002 |

| Sleep disordered breathing | 2.64±1.09 | (0–9) | 2.39±0.77 | (1–8) | 0.011 |

| Daytime sleepiness | 8.94±2.94 | (0–18) | 8.46±2.1 | (4–17) | 0.194 |

| Sleep anxiety | 7.49±2.26 | (3–12) | 5.88±1.5 | (3–10) | 0.001 |

| Total CSHQ score | 49.33±7.93 | (31–68) | 42.88±6.43 | (30–52) | 0.002 |

FA: Food Allergy; CHSQ: Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire; bold represents the significant p-values: p<0.005.

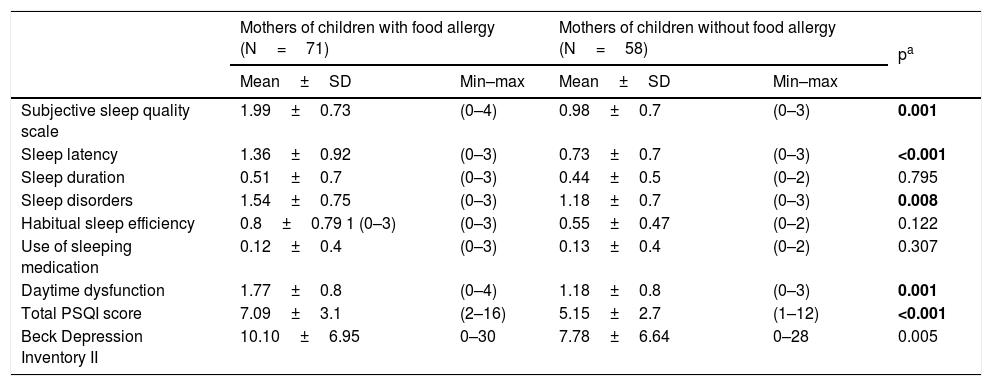

Of the mothers of children with FA 73.6%, with controls 46.5% of them were found to have a sleep problem according to the PSQI. The total PSQI score was significantly higher in mothers of children with FA than in mothers of children without FA (7.09±3.11 vs. 5.15±2.59, Mann Whitney U, p<0.001) indicating that the mothers of children with FA had worse sleep quality. In the subgroups of PSQI regarding subjective sleep quality (p=0.002), sleep latency (p<0.001), sleep disorders (p=0.008), and daytime dysfunction (p=0.001), there was also a statistically significant difference between the two groups. There was no difference in terms of sleep duration (p=0.795), use of sleeping medicine (0.307) and habitual sleep efficiency (p=0.122), between the groups (Table 4).

Comparison of PSQI and Beck Depression Inventory II between mothers.

| Mothers of children with food allergy (N=71) | Mothers of children without food allergy (N=58) | pa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | Min–max | Mean±SD | Min–max | ||

| Subjective sleep quality scale | 1.99±0.73 | (0–4) | 0.98±0.7 | (0–3) | 0.001 |

| Sleep latency | 1.36±0.92 | (0–3) | 0.73±0.7 | (0–3) | <0.001 |

| Sleep duration | 0.51±0.7 | (0–3) | 0.44±0.5 | (0–2) | 0.795 |

| Sleep disorders | 1.54±0.75 | (0–3) | 1.18±0.7 | (0–3) | 0.008 |

| Habitual sleep efficiency | 0.8±0.79 1 (0–3) | (0–3) | 0.55±0.47 | (0–2) | 0.122 |

| Use of sleeping medication | 0.12±0.4 | (0–3) | 0.13±0.4 | (0–2) | 0.307 |

| Daytime dysfunction | 1.77±0.8 | (0–4) | 1.18±0.8 | (0–3) | 0.001 |

| Total PSQI score | 7.09±3.1 | (2–16) | 5.15±2.7 | (1–12) | <0.001 |

| Beck Depression Inventory II | 10.10±6.95 | 0–30 | 7.78±6.64 | 0–28 | 0.005 |

PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; bold represents the significant p-values: p<0.005.

The difference between the groups for the BDI-II s total score was significant. The mothers of children with FA had more depressive symptoms than the mothers of children without FA. The mean total scores of BDI-II was 10.10±6.95 in mothers of children with FA and 7.78±6.64 in mothers of children without FA (Mann Whitney U, p=0.005) (Table 4).

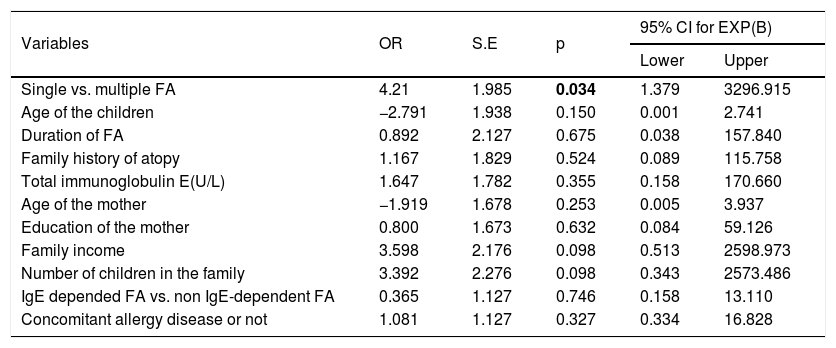

Factors associated with sleep problems in children and mothersThe existence of a sleep disturbance was accepted when the CSHQ total score was over the cut-off point of 41. Binary logistic regression analysis was conducted in order to measure variables affecting the existence of sleep problems in children with FA and their mothers Significant differences were not found for child age (p=0.150), duration of FA (p=0.675), concomitant allergic disease such as asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis and anaphylaxis (p=0.327). There was no relationship between having IgE or non IgE- dependent FA and sleep disorders (p=0.746). Only having multiple food allergies was significant (p=0.034) and brought about a four-fold increased risk of sleep disturbance in children. The association of significant factors with sleep disturbance in children is summarized in Table 5.

Correlates of sleep problems for children: regression analysis.

| Variables | OR | S.E | p | 95% CI for EXP(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Single vs. multiple FA | 4.21 | 1.985 | 0.034 | 1.379 | 3296.915 |

| Age of the children | −2.791 | 1.938 | 0.150 | 0.001 | 2.741 |

| Duration of FA | 0.892 | 2.127 | 0.675 | 0.038 | 157.840 |

| Family history of atopy | 1.167 | 1.829 | 0.524 | 0.089 | 115.758 |

| Total immunoglobulin E(U/L) | 1.647 | 1.782 | 0.355 | 0.158 | 170.660 |

| Age of the mother | −1.919 | 1.678 | 0.253 | 0.005 | 3.937 |

| Education of the mother | 0.800 | 1.673 | 0.632 | 0.084 | 59.126 |

| Family income | 3.598 | 2.176 | 0.098 | 0.513 | 2598.973 |

| Number of children in the family | 3.392 | 2.276 | 0.098 | 0.343 | 2573.486 |

| IgE depended FA vs. non IgE-dependent FA | 0.365 | 1.127 | 0.746 | 0.158 | 13.110 |

| Concomitant allergy disease or not | 1.081 | 1.127 | 0.327 | 0.334 | 16.828 |

FA: food allergy; OR: odds ratio; S.E: standard error; CI: confidence interval, bold represents the significant p-values: p<0.005.

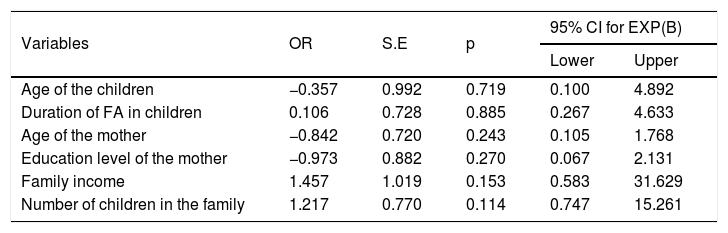

Correlation analysis revealed a significant correlation between CSHQ total score and PSQI total score (r=0.427, p=0.001) and CSOI total score and BDI-II s total score (r=0.265, p=0.01). Additionally, a significant correlation was found between PSQI score and BDI-II s total score (r=0.566, p=0.001). The existence of sleep disturbance in mothers was accepted when the PSQI total score was over the cut-off point of 5. The PSQI total scores were not affected by age, education level, income of the family and the number of children. The association of significant factors with sleep disturbance in mothers is summarized in Table 6.

Correlates of sleep problems for the mothers: binary regression analysis.

| Variables | OR | S.E | p | 95% CI for EXP(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Age of the children | −0.357 | 0.992 | 0.719 | 0.100 | 4.892 |

| Duration of FA in children | 0.106 | 0.728 | 0.885 | 0.267 | 4.633 |

| Age of the mother | −0.842 | 0.720 | 0.243 | 0.105 | 1.768 |

| Education level of the mother | −0.973 | 0.882 | 0.270 | 0.067 | 2.131 |

| Family income | 1.457 | 1.019 | 0.153 | 0.583 | 31.629 |

| Number of children in the family | 1.217 | 0.770 | 0.114 | 0.747 | 15.261 |

OR: odds ratio; S.E: standard error; CI: confidence interval; FA: food allergy, bold represents the significant p-values: p<0.005.

It has been reported that up to 40% of children experience sleep problems during childhood.18 When young children have sleep disruptions, parental sleep is also typically disrupted. Research has demonstrated that parents of children with chronic illnesses experience significant disruption to sleep and daytime functioning, resulting in increased maternal depressive symptoms.19,20

Although the sample size was small, this is one of the first studies to examine sleep disorders both in children with food allergy as well as in their mothers. In this study, we compared sleep problems and the sociodemographic and clinical correlates in children with food allergy and controls. Additionally, we examined the sleep patterns, sleep disturbances, and depressive symptomatology of mothers of children with or without FA. In our study, there was a high rate of sleep disorders in children with FA. Of the children with FA and controls, 83.4% and 50%, respectively, were found to have a sleep problem according to the CSHQ. The mean total scores of the CSHQ were significantly higher in the children with FA than in the controls. Together, these findings highlight the sleep disruptions in children with FA. Allergic diseases have a significant impact on quality of life. The available literature suggests that children with asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis are prone to have more sleep disruption than healthy children.5,8

In our cohort, patients may have had a sleep disorder due to FA alone or due to accompanying allergies. Our patients’ FA represented skin (atopic dermatitis), respiratory (allergic rhinitis and asthma), and/or gastrointestinal tract (GI) symptoms. Sleep disruptions may be reflective of a broader autonomic dysfunction in children with FA. It has been previously described that autonomic dysfunction reflects abnormalities in sympathetic and parasympathetic balance in patients with both allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis.21,22 It is therefore feasible that autonomic dysfunction may in part explain the symptoms of disrupted sleep experienced by our patients with FA. The commonly reported gastrointestinal symptoms of FA include constipation, bloating, and abdominal pain during the night, which may cause sleep disorders. It was highlighted that atopic dermatitis was a stress-responsive disorder that involved the autonomic nervous system.21 Itching and scratching may have caused mental stress and accompanying sleep disorder in our patients, and multiple FAs may have caused more prominent sleep disturbances.

There is limited literature regarding sleep disorders in children with FA. In an article investigating allergic diseases and sleep disorders, FA and atopic dermatitis were shown to cause the most sleep disturbance.8 Wang et al.6 reported that snoring was significantly associated with increased odds of having FA (OR=4.31, 95% CI: 1.17–3.26) and nocturnal waking >2 times per night was associated with a higher risk for FA (OR=3.92, 95% CI: 1.00–15.35).

Previous research on the psychosocial impact of FAs often failed to include data on both children and their mothers’ sleep disorders; therefore, this study puts a different perspective on this subject. Sleep quality of a child was reported to influence the sleep quality of mothers in previous studies.23–25 Compared with healthy families, parents of children with respiratory and atopic disease reported poorer sleep quality.25,26 Parents reported sleep disruptions due to stress related to their child’s health. However, few studies have focused on the effect of FA on parents’ sleep quality. In the present study, we have shown that the mothers of children with FA reported poorer sleep quality than mothers of healthy children. Additionally, we have demonstrated that mothers of children with FA tend to describe themselves as more depressive than mothers of children without FA.

It has been reported that the frequency of depression and anxiety is significant in mothers of children with chronic diseases. Past studies reported that although food allergies affect the entire family, mothers have increased levels of stress and anxiety compared with other family members.9 Chronic sleep deprivation may have caused a negative mood in our mothers of children with FA. Maternal sleep quality has been reported to be a significant predictor of maternal mood and stress. Both the stress and the responsibility of having a child with a chronic disease such as FA, with all the worries and fears it brings about, and the task of caring in itself might disturb the sleep quality of mothers.20,27,28

There are several limitations to this study which should be considered. First, the results are based on a relatively small sample (n=71). Larger samples should be included in future studies. Second, our study was a retrospective cross-sectional study based on mothers’ reports. Given that this study based children’s sleep patterns on maternal reports, it is possible to infer that more anxious and depressive mothers might give information more freely or have more severe sleep patterns, and this situation might have caused recall bias and decreased the reliability of our results. No further objective methods such as actigraphy could be performed due to technical and financial constraints. We could not investigate the relationship between sleep disturbance and quality of life in children with FA. The Turkish Food Allergy Quality of Life Questionnaire (FAQLQ-PF)2 was not available during the study. Despite these limitations, this study provides important information regarding sleep disruptions in children with FA and their mothers.

In conclusion, FAs have a negative effect on both children and their parents’ social life. The presence of an FA in a child may be associated with deteriorated sleep quality in children and mothers as well as increased depressive symptoms in mothers. These findings emphasize that physicians should be aware of sleep problems during follow-up, considering the high frequencies of sleep disturbances accompanying allergic disease as FA. Pediatric psychologists should also work with medical and multidisciplinary teams to help allergists understand the impact of mother sleep deprivation.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. We thank Dr. Meral Bilgilisoy Filiz for assistance with statistical analysis.

The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Antalya Training and Research Hospital.