Symptom-based score (SBS) quantifies the number and severity of suspected cow's milk-related symptoms. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the efficiency of SBS in patients diagnosed with cow's milk protein (CMPA) and hen's egg allergy (HEA).

Materials and methodsA single-center study was conducted between June 2015 and August 2017. Infants who were diagnosed with CMPA and HEA or both were enrolled in the study. SBS was applied at baseline and at one month during an elimination diet.

ResultsOne hundred and twelve patients were enrolled in the study. Of these, 56 (50%) were female. Forty-nine (43.8%) patients were diagnosed with CMPA, 39 (34.8%) patients were diagnosed with HEA and 24 (21.4%) patients were diagnosed with cow's milk protein and hen's egg allergy (CMPHEA).

In the analysis of SBS, median Bristol scale and initial total symptom-based scores were significantly lower in the HEA group than others (p=0.002; p=0.025). After the elimination diet, mean SBS decrease in the CMPHEA group (11.3±4.7) was found to be higher than CMPA (8.8±3.7) and HEA (8.0±4.0) groups (p=0.009). In 41 (83.7%) patients with CMPA, 33 (84.6%) patients with HEA and 21 (87.5%) patients with CMPHEA, a ≥50% decrease in SBS was observed after the elimination diet.

ConclusionWe may conclude that the present study suggests that SBS can be useful in monitoring the response to elimination diet in infants diagnosed with cow's milk protein and hen's egg allergy.

Food allergy (FA) affects nearly 8% of children, with growing evidence of an increase in prevalence. Cow's milk protein allergy (CMPA) (affecting approximately 2% of children under four years of age) and hen's egg allergy (HEA) (0.5–2.5% of young children) are the most frequent causes of FA in children.1 Similar to other food allergies, the majority of patients have at least two symptoms, and symptoms that affect at least two organ systems. Approximately 50–70% of the patients have cutaneous symptoms; 50–60% have gastrointestinal symptoms and about 20–30% have respiratory symptoms.2 Although medical history, physical examination and diagnostic investigations (IgE, skin-prick test) are important, the specificity and sensitivity of these tests and clinical findings are not sufficient to establish an appropriate diagnosis of FA. While the double-blind challenge test is accepted as the gold standard test, clinicians often prefer open food challenges in the diagnosis of FA. However, oral food challenge (OFC) should be performed under medical supervision of an allergist, and often causes anxiety and fear for the parents.3–6

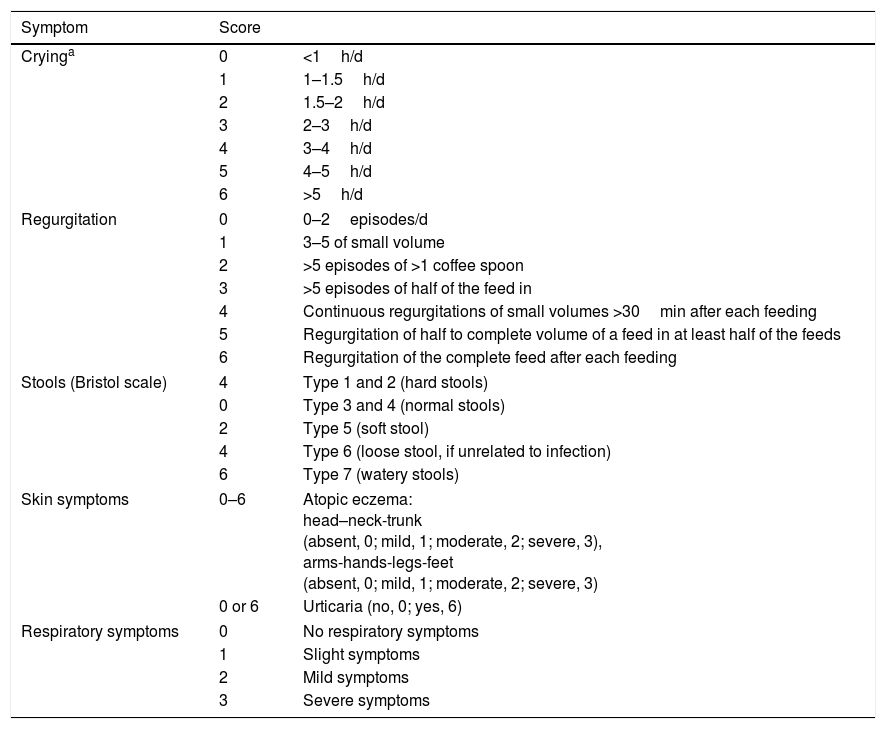

The prevalence of FA has been increasing in recent decades, particularly in westernized countries.7 On the other hand, diagnosing FA is difficult as there is no pathognomonic symptom or reliable diagnostic test. As patients typically present to their primary care physicians first, these doctors have a crucial role in making the diagnosis, submitting the appropriate referrals and coordinating other support for care.8 Having a simple and time efficient scoring tool would help to make diagnosis of FA. Recently, Vandenplas et al. developed the symptom-based score (SBS) which was renamed as Cow's Milk-related-Symptom-Score (CoMiSS™) to quantify the number and severity of suspected cow's milk-related symptoms by considering the general manifestations together with dermatological, gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms (Table 1).9,10 The aim of SBS is to increase awareness and recognition of cow's milk-related symptoms, help in decision-making and correct management, and prevent over- and under-diagnosis. The symptom-based score is also used to monitor the response to elimination diet.

Symptom-based score.9

| Symptom | Score | |

|---|---|---|

| Cryinga | 0 | <1h/d |

| 1 | 1–1.5h/d | |

| 2 | 1.5–2h/d | |

| 3 | 2–3h/d | |

| 4 | 3–4h/d | |

| 5 | 4–5h/d | |

| 6 | >5h/d | |

| Regurgitation | 0 | 0–2episodes/d |

| 1 | 3–5 of small volume | |

| 2 | >5 episodes of >1 coffee spoon | |

| 3 | >5 episodes of half of the feed in | |

| 4 | Continuous regurgitations of small volumes >30min after each feeding | |

| 5 | Regurgitation of half to complete volume of a feed in at least half of the feeds | |

| 6 | Regurgitation of the complete feed after each feeding | |

| Stools (Bristol scale) | 4 | Type 1 and 2 (hard stools) |

| 0 | Type 3 and 4 (normal stools) | |

| 2 | Type 5 (soft stool) | |

| 4 | Type 6 (loose stool, if unrelated to infection) | |

| 6 | Type 7 (watery stools) | |

| Skin symptoms | 0–6 | Atopic eczema: head–neck-trunk (absent, 0; mild, 1; moderate, 2; severe, 3), arms-hands-legs-feet (absent, 0; mild, 1; moderate, 2; severe, 3) |

| 0 or 6 | Urticaria (no, 0; yes, 6) | |

| Respiratory symptoms | 0 | No respiratory symptoms |

| 1 | Slight symptoms | |

| 2 | Mild symptoms | |

| 3 | Severe symptoms | |

To date, SBS has been used in several studies of patients with CMPA, but has not been validated in a general population with regard to its sensitivity to detect CMPA and HEA. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy and utility of SBS in monitoring the response to elimination diet in not only CMPA patients, but also in patients diagnosed with HEA.

Material and methodsA single-center study was conducted between June 2015 and August 2017 in the Pediatric Immunology and Allergy Outpatient Clinic. Breastfed and formula-fed patients under one year of age who were diagnosed with CMPA and HEA or both were enrolled in the study. Patients who had an infection affecting the respiratory and/or gastrointestinal system during the period of the observed one month were excluded from the study. Demographics (age, gender, family history of atopy) and laboratory (IgE) findings of the patients were recorded. All patients were classified into IgE-mediated, non-IgE-mediated and mixed immune reaction type groups according to clinical and laboratory findings. SBS was applied at baseline and at one month during an elimination diet. Cut-off values were determined as initial total SBS ≥12, ≥10 and a reduction of ≥25% and ≥50% in SBS after the elimination diet as described in previous studies.10–12

Ethical approvalThe study protocol was designed in compliance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from parents upon enrollment in the study. This study has been granted approval by the University Research Ethics Board.

Diagnosis of CMPA and HEAThe diagnosis of cow's milk protein and hen's egg allergy was established with directed history, physical examination and OFC or laboratory findings with positive skin-prick test.

In patients diagnosed with IgE-mediated type immune reaction, cow's milk-specific IgE>5kU/L and/or egg white-specific IgE>2kU/L using immunoCAP with a positive skin-prick test (≥3mm) which has a 95% predictive value was accepted as diagnostic for CMPA and/or HEA, respectively.13

In exclusively breastfed infants under six months of age with mixed type and non-IgE mediated CMPA and/or HEA, cow's milk and/or hen's egg was eliminated from the maternal diet for four weeks. In patients with improved symptoms, recurrence of symptoms after reintroduction of cow's milk and/or hen's egg in maternal diet was diagnostic for CMPA and/or HEA.14,15 In formula-fed infants, diagnosis of food allergy was established with previously reported protocols for OFC, and extensively hydrolyzed formula was used in elimination diet.6 In patients older than six months of age consuming hen's egg, OFC was performed according to the previously described protocol.16 Both cow's milk allergy and hen's egg allergy were diagnosed by performing the same elimination and challenge methods mentioned above. Oral food challenges were performed under medical supervision.

Statistical analysisStatistical data analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) computer software (version 20.0; Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical variables were expressed as number and percentage (%). Continuous variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation (minimum–maximum) and median [25th–75th percentile] according to the normality of variables. The normality of data was determined with Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. Categorical data (gender, family history of atopy) were compared by the Chi-square test. While one-way ANOVA was used to compare the normally distributed data (age, decrease of SBS, percentage decrease of SBS), the Kruskal–Wallis test was performed to assess data with a non-parametric distribution (IgE, crying, regurgitation, Bristol scale, atopy, urticaria, respiratory symptoms, total symptom-based scores at baseline and after the elimination diet) across the groups. Friedman test was performed to assess the changes in SBS before and after the elimination diet in all groups. A two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

ResultsOne hundred and twelve patients were enrolled in the study. Of these, 56 (50%) were female. Mean age at the time of diagnosis was 5.6±2.2 months (2–10). Family history of atopy was determined in 81 (72.3%) patients. Seventy-five patients were exclusively breastfed and 37 were formula-fed. No infants were fed both formula and breast milk. Forty-nine (43.8%) patients were diagnosed with CMPA, 39 (34.8%) patients were diagnosed with HEA and 24 (21.4%) patients had cow's milk protein and hen's egg allergy (CMPHEA). FA diagnosis was established by OFC in 46 patients and by specific IgE with positive skin-prick test in 66 patients. Anaphylactic reaction was not detected in any of the patients. IgE-mediated, non-IgE-mediated and mixed type immune reaction types were detected in 26 (23.2%), 32 (28.6%) and 54 (48.2%) patients, respectively.

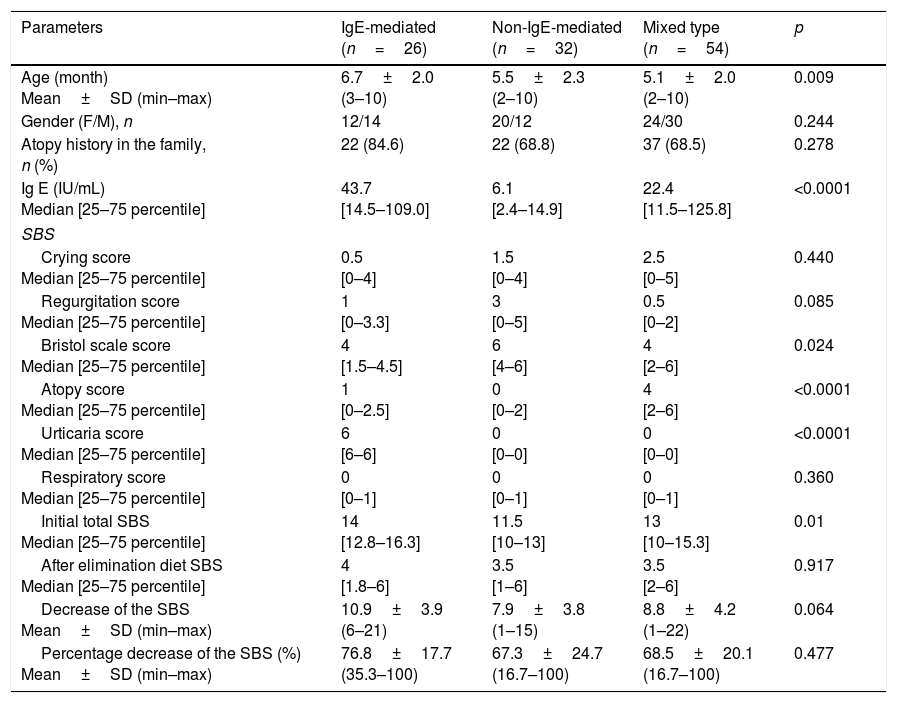

In the analysis of IgE-mediated, non-IgE-mediated and mixed type reaction groups, there were no significant differences in terms of gender and family history of atopy. Age was significantly higher in the IgE-mediated group (6.7±2.0 months) than the non-IgE-mediated (5.5±2.3 months) and mixed type (5.1±2.0 months) groups (p=0.009). Median IgE level was higher in the IgE-mediated group compared to other groups (p<0.0001) (Table 2).

Comparison of IgE-mediated, non-IgE-mediated and mixed type allergic reaction groups.

| Parameters | IgE-mediated (n=26) | Non-IgE-mediated (n=32) | Mixed type (n=54) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (month) Mean±SD (min–max) | 6.7±2.0 (3–10) | 5.5±2.3 (2–10) | 5.1±2.0 (2–10) | 0.009 |

| Gender (F/M), n | 12/14 | 20/12 | 24/30 | 0.244 |

| Atopy history in the family, n (%) | 22 (84.6) | 22 (68.8) | 37 (68.5) | 0.278 |

| Ig E (IU/mL) Median [25–75 percentile] | 43.7 [14.5–109.0] | 6.1 [2.4–14.9] | 22.4 [11.5–125.8] | <0.0001 |

| SBS | ||||

| Crying score Median [25–75 percentile] | 0.5 [0–4] | 1.5 [0–4] | 2.5 [0–5] | 0.440 |

| Regurgitation score Median [25–75 percentile] | 1 [0–3.3] | 3 [0–5] | 0.5 [0–2] | 0.085 |

| Bristol scale score Median [25–75 percentile] | 4 [1.5–4.5] | 6 [4–6] | 4 [2–6] | 0.024 |

| Atopy score Median [25–75 percentile] | 1 [0–2.5] | 0 [0–2] | 4 [2–6] | <0.0001 |

| Urticaria score Median [25–75 percentile] | 6 [6–6] | 0 [0–0] | 0 [0–0] | <0.0001 |

| Respiratory score Median [25–75 percentile] | 0 [0–1] | 0 [0–1] | 0 [0–1] | 0.360 |

| Initial total SBS Median [25–75 percentile] | 14 [12.8–16.3] | 11.5 [10–13] | 13 [10–15.3] | 0.01 |

| After elimination diet SBS Median [25–75 percentile] | 4 [1.8–6] | 3.5 [1–6] | 3.5 [2–6] | 0.917 |

| Decrease of the SBS Mean±SD (min–max) | 10.9±3.9 (6–21) | 7.9±3.8 (1–15) | 8.8±4.2 (1–22) | 0.064 |

| Percentage decrease of the SBS (%) Mean±SD (min–max) | 76.8±17.7 (35.3–100) | 67.3±24.7 (16.7–100) | 68.5±20.1 (16.7–100) | 0.477 |

SD: standard deviation; F: female; M: male.

While median Bristol scale score was higher in the non-IgE-mediated group (p=0.0024), atopy score was higher in the mixed type reaction group (p<0.0001). Urticaria score was found to be significantly higher in the IgE-mediated group than others (p<0.0001). Initial total SBS was lower in the non-IgE-mediated group (p=0.01). In the comparison of IgE-mediated, non-IgE-mediated and mixed type reaction groups, there were no differences in terms of crying, regurgitation, respiratory symptoms, and total symptom-based scores after the elimination diet. Mean decrease and mean percentage decrease of SBS after the elimination diet did not differ between the groups (Table 2).

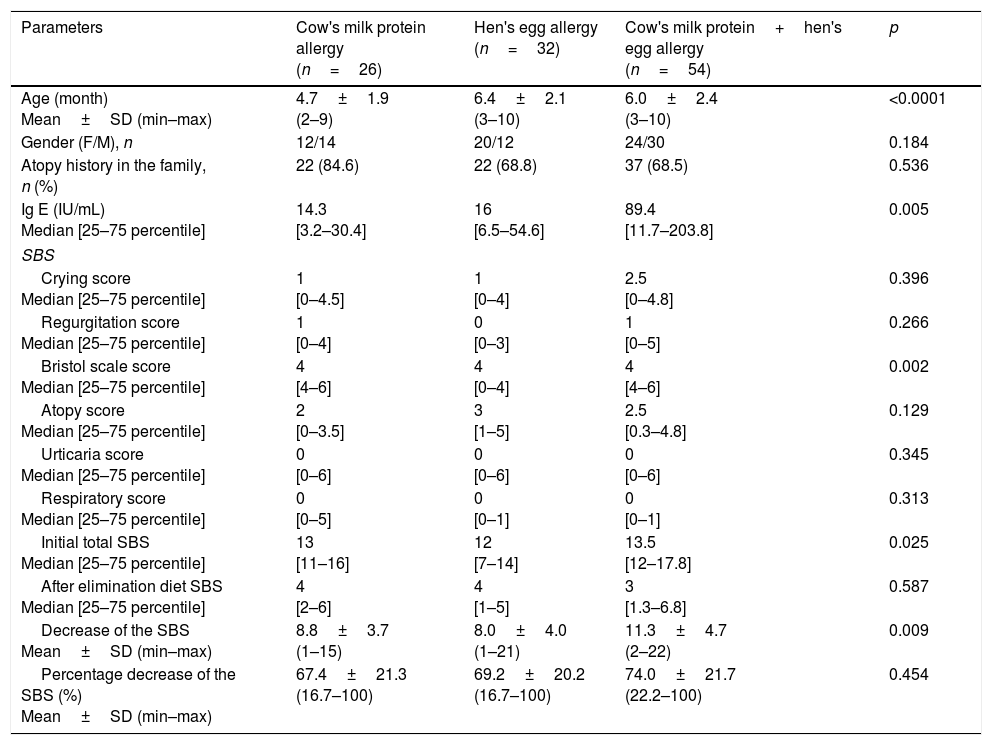

In the comparison of CMPA, HEA and CMPHEA groups, the mean age in the CMPA group (4.7±1.9 months) was significantly lower than the HEA (6.4±2.1 months) and CMPHEA (6.0±2.4 months) groups (p<0.0001). In the CMPHEA group, median IgE levels were higher (89.4) than CMPA (14.3) and HEA (16) (p=0.005). There were no differences between the groups in terms of family history of atopy and gender (Table 3).

Comparison of cow's milk protein (CMPA), hen's egg (HEA) and cow's milk protein and hen's egg (CMPHEA) allergy groups.

| Parameters | Cow's milk protein allergy (n=26) | Hen's egg allergy (n=32) | Cow's milk protein+hen's egg allergy (n=54) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (month) Mean±SD (min–max) | 4.7±1.9 (2–9) | 6.4±2.1 (3–10) | 6.0±2.4 (3–10) | <0.0001 |

| Gender (F/M), n | 12/14 | 20/12 | 24/30 | 0.184 |

| Atopy history in the family, n (%) | 22 (84.6) | 22 (68.8) | 37 (68.5) | 0.536 |

| Ig E (IU/mL) Median [25–75 percentile] | 14.3 [3.2–30.4] | 16 [6.5–54.6] | 89.4 [11.7–203.8] | 0.005 |

| SBS | ||||

| Crying score Median [25–75 percentile] | 1 [0–4.5] | 1 [0–4] | 2.5 [0–4.8] | 0.396 |

| Regurgitation score Median [25–75 percentile] | 1 [0–4] | 0 [0–3] | 1 [0–5] | 0.266 |

| Bristol scale score Median [25–75 percentile] | 4 [4–6] | 4 [0–4] | 4 [4–6] | 0.002 |

| Atopy score Median [25–75 percentile] | 2 [0–3.5] | 3 [1–5] | 2.5 [0.3–4.8] | 0.129 |

| Urticaria score Median [25–75 percentile] | 0 [0–6] | 0 [0–6] | 0 [0–6] | 0.345 |

| Respiratory score Median [25–75 percentile] | 0 [0–5] | 0 [0–1] | 0 [0–1] | 0.313 |

| Initial total SBS Median [25–75 percentile] | 13 [11–16] | 12 [7–14] | 13.5 [12–17.8] | 0.025 |

| After elimination diet SBS Median [25–75 percentile] | 4 [2–6] | 4 [1–5] | 3 [1.3–6.8] | 0.587 |

| Decrease of the SBS Mean±SD (min–max) | 8.8±3.7 (1–15) | 8.0±4.0 (1–21) | 11.3±4.7 (2–22) | 0.009 |

| Percentage decrease of the SBS (%) Mean±SD (min–max) | 67.4±21.3 (16.7–100) | 69.2±20.2 (16.7–100) | 74.0±21.7 (22.2–100) | 0.454 |

SD: standard deviation, F: female, M: male.

In the analysis of SBS, median initial SBS was 13 [11–16], 12 [7–14] and 13.4 [12–17.8] for CMPA, HEA and CMPHEA groups, respectively. Bristol scale and initial total symptom-based scores were significantly lower in the HEA group than others (p=0.002; p=0.025). After the elimination diet, the mean decrease of SBS in the CMPHEA group (11.3±4.7) was found to be higher than CMPA (8.8±3.7) and HEA (8.0±4.0) groups (p=0.009). There were no differences between the three groups in terms of crying, regurgitation, atopy, urticaria, respiratory symptoms, and symptom-based scores and percentage decrease of symptom-based scores after the elimination diet (Table 3). SBS decrease was not ≥3 points in seven (6.3%) patients (three CMPA, three HEA and one CMPHEA).

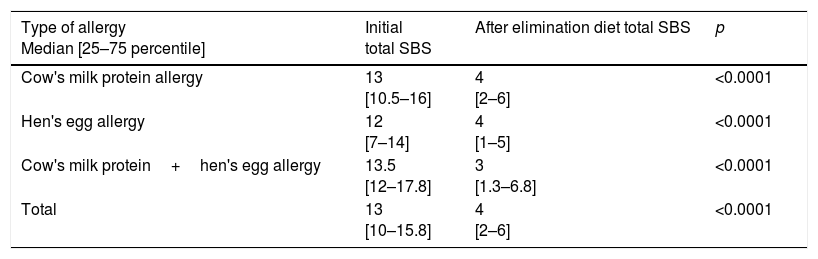

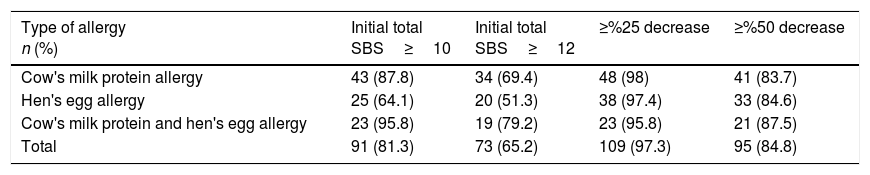

While initial total SBS was ≥10 in 43 (87.8%) patients with CMPA, 25 (64.1%) patients with HEA and 23 (95.8%) patients with CMPHEA; it was ≥12 in 34 (69.4%) patients with CMPA, 20 (51.3%) patients with HEA and 19 (79.2%) patients with CMPHEA. After the elimination diet, ≥25% decrease in SBS was detected in 48 patients (98%) with CMPA, 38 (97.4%) patients with HEA and 23 (95.8%) patients with CMPHEA. In 41 (83.7%) patients with CMPA, 33 (84.6%) patients with HEA and 21 (87.5%) patients with CMPHEA, ≥50% decrease in SBS was determined after the elimination diet (Table 4). With the elimination diet, a statistically significant decrease in the SBS was observed in CMPA, HEA, CMPHEA and total groups (Table 5).

Evaluation of the decrease in SBS after elimination diet.

| Type of allergy Median [25–75 percentile] | Initial total SBS | After elimination diet total SBS | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cow's milk protein allergy | 13 [10.5–16] | 4 [2–6] | <0.0001 |

| Hen's egg allergy | 12 [7–14] | 4 [1–5] | <0.0001 |

| Cow's milk protein+hen's egg allergy | 13.5 [12–17.8] | 3 [1.3–6.8] | <0.0001 |

| Total | 13 [10–15.8] | 4 [2–6] | <0.0001 |

Cut-off values of SBS.

| Type of allergy n (%) | Initial total SBS≥10 | Initial total SBS≥12 | ≥%25 decrease | ≥%50 decrease |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cow's milk protein allergy | 43 (87.8) | 34 (69.4) | 48 (98) | 41 (83.7) |

| Hen's egg allergy | 25 (64.1) | 20 (51.3) | 38 (97.4) | 33 (84.6) |

| Cow's milk protein and hen's egg allergy | 23 (95.8) | 19 (79.2) | 23 (95.8) | 21 (87.5) |

| Total | 91 (81.3) | 73 (65.2) | 109 (97.3) | 95 (84.8) |

The most important aspect of the present study is the finding that SBS can be effectively used to monitor the response to an elimination diet not only in patients with CMPA but also in those diagnosed with HEA. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the efficiency of SBS in patients with hen's egg allergy to date.

It is well known that urticaria, angioedema, diarrhea, vomiting and anaphylaxis are IgE-mediated symptoms and malabsorption, constipation, villous atrophy, eosinophilic enterocolitis and proctocolitis are non-IgE-mediated symptoms. Consistently, in our study, atopy score, urticarial score and Bristol scale score were found to be higher in mixed type reaction, IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated, respectively. These findings suggest that SBS may be helpful to clarify the allergic reaction type, as expected.17,18

The initial symptom-based score was lower in the HEA group than the others, which may be explained with the low Bristol scale score in the HEA group. Although previous studies indicated that 2/3 of children with HEA exhibited gastrointestinal symptoms, we determined that stool symptoms were not remarkable in patients with hen's egg allergy compared to those with cow's milk protein allergy.19 We think that the lack of stool symptoms and only 51.3% of the subjects alone had an SBS >12 in the HEA group pose challenges to using the SBS for the diagnosis of HEA. In CMPA, HEA and CMPHEA groups, SBS dramatically decreased with the elimination diet. With these findings, we can conclude that SBS which was developed to evaluate the symptoms related to cow's milk and renamed as Cow's Milk-related-Symptom-Score (CoMiSS™) is applicable in patients with hen's egg allergy to objectively evaluate the response to elimination diet.

In previous studies, arbitrary cut-off values were determined as initial SBS ≥12, ≥10 and a decrease of ≥6 points (≥50%) and ≥3 points (≥25%) in the score to determine infants at risk of CMPA.12,20 A ≥12 SBS score at baseline with ≥50% decrease indicated the best predictive factor for a positive challenge test, and the predictive value of SBS was 80% if the score was ≥12 at baseline, with a decrease of ≥6.11,12 In our study, initial SBS was ≥12 in 69.4% of CMPA patients, 51.3% of HEA and 79.2% of CMPHEA. At a minimum, similar to previous studies, the sensitivity of a ≥50% decrease in the score was determined as 87.3%, 84.6% and 84.8% in CMPA, HEA and CMPHEA, respectively. Although the decrease in SBS by ≥25% was more sensitive to diagnose FA (98% in CMPA, 97.4% in HEA and 95.8% CMPHEA), we thought that specificity could be low with this cut-off value. As mentioned in previous studies,12,20 our findings led us to using the ≥50% decrease in the score as the cut-off value in SBS for the diagnosis of FA. Unfortunately, the determination of specificity of SBS, which we could not perform due to the fact that healthy infants were not included in study, is necessary to define the most appropriate cut-off value.

Symptom-based score is calculated with the physical examination findings of the clinician and the symptoms reported by parents. This makes SBS subjective and limits the utility of the score. However, re-evaluation of the score with the same physician and the same family member after the elimination diet may reduce the subjectivity of this score. Therefore, while determining the cut-off value for SBS, we considered that the decrease in the score with the elimination diet is a more appropriate approach than assessment of the initial SBS.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, all patients included in the study were not diagnosed by OFC, which is the gold standard test for the diagnosis of FA. We enrolled patients diagnosed with specific IgE test and SPT. Secondly, SBS was not evaluated in the healthy population as it would not be ethical to expose healthy infants to an elimination diet and a challenge test, and this results in limitations regarding the analysis of sensitivity as well as the positive and negative predictive values of the score. Thirdly, the limited number of subjects in subgroups precluded a better evaluation of SBS and its sub-categories in each FA group.

As a result, we may conclude that this study shows that SBS can be useful in monitoring the response to elimination diet in infants diagnosed with cow's milk protein and hen's egg allergy. However, the lack of stool symptoms and that only half of the subjects alone had an SBS >12 in the HEA group pose challenges to using the SBS for the diagnosis of HEA. The score may increase the awareness of symptoms caused by FA among primary care clinicians. Future studies involving a healthy control group and a larger population would help to better identify the validity and cut-off values of SBS.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.