Food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis (FPIAP) is characterised by inflammation of the distal colon in response to one or more food proteins. It is a benign condition of bloody stools in a well-appearing infant, with usual onset between one and four weeks of age.

ObjectiveOur objective was to examine the clinical properties of patients with FPIAP, tolerance development time as well as the risk factors that affect tolerance development.

MethodsThe clinical symptoms, offending factors, laboratory findings, methods used in the diagnosis and tolerance development for 77 patients followed in the Paediatric Allergy and Gastroenterology Clinics with the diagnosis of FPIAP during January 2010–January 2015 were examined in our retrospective cross-sectional study.

ResultsThe starting age of the symptoms was 3.3±4.7 months (0–36). Milk was found as the offending substance for 78% of the patients, milk and egg for 13% and egg for 5%. Mean tolerance development time of the patients was 14.7±11.9 months (3–66 months). Tolerance developed before the age of one year in 40% of the patients. Tolerance developed between the age of 1–2 years in 27%, between the age of 2–3 years in 9% and after the age of 3 years in 5% of the patients.

ConclusionsSmaller onset age and onset of symptoms during breastfeeding were found associated with early tolerance development. In the majority of the patients, FPIAP resolves before the age of one year, however in some of the patients this duration may be much longer.

The prevalence of food allergy has increased in recent decades, especially in the paediatric population.1,2 According to the World Allergy Organisation guidance, food allergy can be IgE-mediated or non-IgE-mediated.3 Even though the mechanism and pathogenesis of IgE-mediated food allergy are understood much better, the mechanism and pathogenesis of non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergies are still unclear. Food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis (FPIAP) is one of these.2 FPIAP starts usually during the first months of life in otherwise healthy infants. FPIAP is characterised by mucus, blood and foam in the stool. The patients do not have growth retardation; however, weight gain may be slow. Mild anaemia and hypoalbuminaemia are rarely observed. FPIAP was first defined in 1982 by Lake et al. in six breastfed infants.1,2,4 The most common offending food that has been reported until now is cow's milk.2,4 Approximately 60% of cases occur in breastfed infants. It is postulated that ingestion of allergen food proteins from human breast milk causes inflammatory response in rectum and distal sigmoid colon.2,4

There is no specific diagnosis test for FPIAP. The diagnosis is made based on improvement in gross bleeding with the elimination of the offending food in 72–96h and the recurrence of the symptoms following food challenge.2,4,6 Infants with proctocolitis become tolerant to the offending food by one to three years of age and the majority of the patients achieve clinical tolerance by one year. Up to 20% of breastfed infants have spontaneous resolution of bleeding without changes in the maternal diet.7 The long-term prognosis is excellent, there are no reports of inflammatory bowel disease development in infants with FPIAP followed for more than 10 years.4

Data about prevalence, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of FPIAP is limited and factors that affect prognosis are not exactly known. Our objective was to examine the clinical properties of FPIAP patients, tolerance development time and the risk factors that have effects on tolerance development.

Methods and materialsFPIAP definitionIn the study, the diagnosis of allergic proctocolitis is defined according to the criteria suggested in the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) food allergy and anaphylaxis guidelines and the expert panel report (Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Food Allergy in the United States). These guidelines suggest the use of: “history, improvement of symptoms by eliminating the offending food, recurrence of symptoms following oral food challenge (OFC)”.8

Data collectionThis crosssectional retrospective study was performed in BehcetUz Children's Hospital Department of Paediatric Allergy and Gastroenterology, between January 2010 and January 2015. The clinical properties, laboratory data, diagnostic procedures and data about tolerance development of 77 patients with the diagnosis of FPIAP were evaluated. Patients with missing data in their files, patients for whom FPIAP diagnosis could not be verified via challenge following elimination, patients with infections leading to bloody diarrhoea, patients with anal fissure, perianal dermatit/excoriations, invagination, coagulation defects, necrotising enterocolitis, inflammatory bowel diseases, vitamin K deficiency and immunodeficiency were excluded.

Skin prick tests (SPT), specific IgEIn patients with additional atopic findings such as atopic dermatitis, recurrent wheezing, anaphylaxis, both food specific IgE test and SPT were performed. SPT was applied via prick microlancet (stallerpoint) method for the most common allergens (ALK-Abellò (Madrid, Spain); cow and goat's milk, soy, egg, wheat, fish, pistachio, sesame) to all patients and for the foods that the family of the patient was suspicious about to specific patients. Histamine (10mg/mL) and physiological saline (ALK-Abellò (Madrid, Spain)) were used as positive and negative references, respectively. Skin reactions were evaluated 20min after the skin test. A positive reaction was characterised as wheal diameter ≥3mm. Specific IgE levels were measured using the immuno-CAP system (Phadia, Uppsala, Sweden). 0.35kUa/L was taken as the cut-off value.

Atopy patch test (APT)Fresh food was applied to the back of the patient via finnchamber (aluminium disc). The tested region was evaluated 48 and 72h later.9 Isotonic saline was applied as negative control. APT reactions were graded as per the European Task Force for Atopic Dermatitis consensus report.10

Oral food challenge (OFC) and age of resolutionMilk and milk products were eliminated from the diet of the mothers for breastfed infants. Primarily extensively hydrolysed formulas (eHF) were used. In patients unresponsive to eHF or in patients considered to be with multiple food allergy, aminoacid based formulas were preferred. The formula was replaced with extensively hydrolysed formula (eHF) or aminoacid-based formula for formula-fed infants. In infants, for whom clinical improvement was observed within 72–96h (complete resolution in the stool sample can take one week if there is significant blood), the offending food was restarted in the third week. The patient was diagnosed with FPIAP if the offending food caused rectal bleeding, diarrhoea and mucus again in the provocation period. If there was no response with the first step diet with eHF or aminoacid based formula, egg and wheat products were eliminated from the diet of the mother of the infant to be started again three weeks after for provocation. Elementary diet was preferred in case there was no response to milk, egg and wheat products in patients with multiple food allergies. Foods were started one by one after all the symptoms were resolved with the elimination diet and in this manner, the offending food was tried to be determined. For less frequent probable offending foods such as carrot and apple, the diagnosis was made by elimination and provocation of the probable offending food that was suspected from the patients’ history.

Patients who passed OFC during the follow up or who completely tolerated the food at home were accepted as treated. OFC was repeated in our clinic with six-month intervals. Challenge protocol was carried out based on FA work group report and EAACI position paper.11,12 Patients for whom no reaction was observed during OFC continue to take food at home and the families were warned regarding late phase reactions. Mothers of some children tested at home whether there was any improvement or not. As a result, the diet was terminated if the symptoms were not observed again and the patient follow up was discontinued. Diet was continued in patients for whom symptoms restarted and OFC was repeated every six months.

Endoscopy and histologyEndoscopic examination was carried out by a paediatric gastroenterologist on infants with multiple food allergies, late symptoms, gross bleeding and anaemia in order to verify the diagnosis and to eliminate the other reasons for rectal bleeding. Histological examination was carried out by a pathologist.

Statistical analysisStatistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS for Windows 15.0 Chicago, USA) programme was used to analyse the data. Results were given as either mean±standard deviation (SD) or median (min–max) according to the distribution. The Chi-squared test was used to compare grouped data. The paired t-test was used to compare group-specific measurements, and the independent Student's t-test to compare measurements among independent groups. Kruskal–Wallis test and Mann–Whitney U tests were used for non-normally distributed variables. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

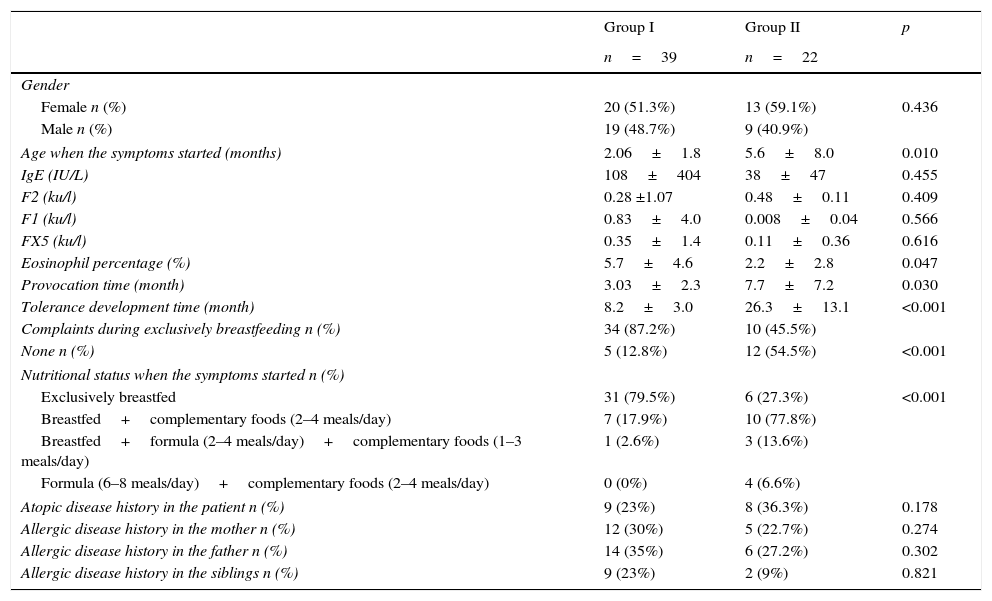

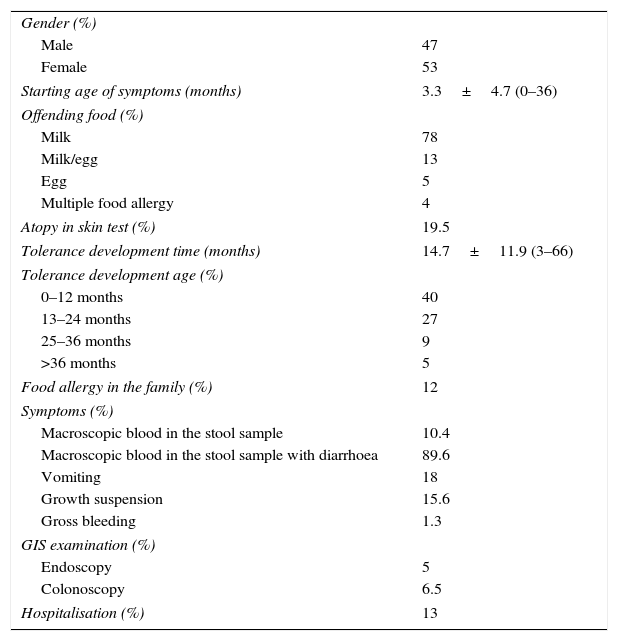

ResultsIn the study, 47% (n=36) of the 77 patients diagnosed with FPIAP were male, 53% (n=41) were female. The mean age when the symptoms started was 3.31±4.794 months. The smallest patient was seven days old, whereas the patient who was the oldest when the symptoms started was 36 months old. 13% (n=10) of the patients were hospitalised. 12% (n=9) have a family history of food allergy. Food elimination and provocation were applied to all patients for diagnosis. Symptomatic patients during exclusive breastfeeding period, recovered by elimination of milk and milk products from the diet of the mother. From these patients who came at the complementary feeding period, milk and milk products were not administered until tolerance development occurred. APT was performed in only nine (12%) of the patients. Reaction was not observed in any of the patients after patch test. In other cases, parents of the children did not give approval for APT. In patients with additional atopic findings such as atopic dermatitis, recurrent wheezing, anaphylaxis, both food specific IgE test and SPT were performed. Symptoms started while still being breastfed in 53% (n=41) of the patients. The offending substance was determined as milk for 78% (n=60) of the patients, egg for 5% (n=4), milk and egg for 13% (n=10). Multiple food allergy was observed in three patients. The other foods determined were wheat with 3.9% (n=3), sesame with 2.6% (n=2), meat 1.3% (n=1), fish with 1.3% (n=1), carrot with 1.3% (n=1) and apple with 1.3% (n=1). These foods were determined in patients with multiple food allergy in addition to milk and egg. When cases younger and older than one year were compared, it was determined that earlier tolerance development was observed in children with smaller symptom onset age. Also, early tolerance developed in cases whose symptoms appeared while still being breastfed. The eosinophil count was greater in the below one year of age group; whereas there was no difference in the other parameters (Table 1). In Table 2, clinical and laboratory data of the patients, who developed tolerance before six months old and between 6 and 12 months old, were compared. No statistically significant difference was found (Table 2).

Comparison of the demographic properties for cases (group I) that developed tolerance before 12 months old (group I) and those that developed tolerance after 12 months old (group II).

| Group I | Group II | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=39 | n=22 | ||

| Gender | |||

| Female n (%) | 20 (51.3%) | 13 (59.1%) | 0.436 |

| Male n (%) | 19 (48.7%) | 9 (40.9%) | |

| Age when the symptoms started (months) | 2.06±1.8 | 5.6±8.0 | 0.010 |

| IgE (IU/L) | 108±404 | 38±47 | 0.455 |

| F2 (ku/l) | 0.28 ±1.07 | 0.48±0.11 | 0.409 |

| F1 (ku/l) | 0.83±4.0 | 0.008±0.04 | 0.566 |

| FX5 (ku/l) | 0.35±1.4 | 0.11±0.36 | 0.616 |

| Eosinophil percentage (%) | 5.7±4.6 | 2.2±2.8 | 0.047 |

| Provocation time (month) | 3.03±2.3 | 7.7±7.2 | 0.030 |

| Tolerance development time (month) | 8.2±3.0 | 26.3±13.1 | <0.001 |

| Complaints during exclusively breastfeeding n (%) | 34 (87.2%) | 10 (45.5%) | |

| None n (%) | 5 (12.8%) | 12 (54.5%) | <0.001 |

| Nutritional status when the symptoms started n (%) | |||

| Exclusively breastfed | 31 (79.5%) | 6 (27.3%) | <0.001 |

| Breastfed+complementary foods (2–4 meals/day) | 7 (17.9%) | 10 (77.8%) | |

| Breastfed+formula (2–4 meals/day)+complementary foods (1–3 meals/day) | 1 (2.6%) | 3 (13.6%) | |

| Formula (6–8 meals/day)+complementary foods (2–4 meals/day) | 0 (0%) | 4 (6.6%) | |

| Atopic disease history in the patient n (%) | 9 (23%) | 8 (36.3%) | 0.178 |

| Allergic disease history in the mother n (%) | 12 (30%) | 5 (22.7%) | 0.274 |

| Allergic disease history in the father n (%) | 14 (35%) | 6 (27.2%) | 0.302 |

| Allergic disease history in the siblings n (%) | 9 (23%) | 2 (9%) | 0.821 |

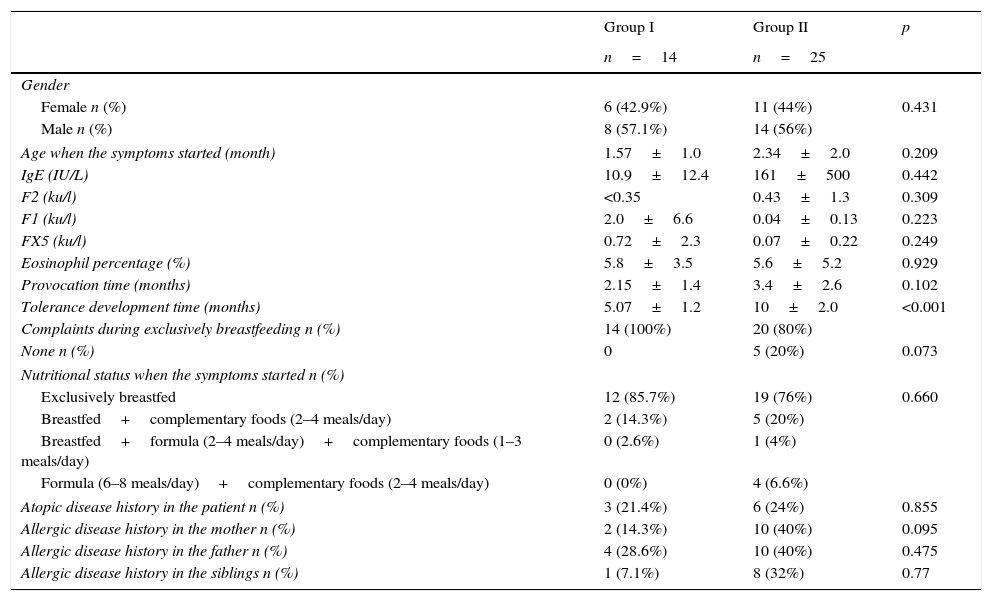

Comparing demographic properties of the patients, who developed tolerance at or before six months old (group I), between 6 and 12 months old (group II).

| Group I | Group II | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=14 | n=25 | ||

| Gender | |||

| Female n (%) | 6 (42.9%) | 11 (44%) | 0.431 |

| Male n (%) | 8 (57.1%) | 14 (56%) | |

| Age when the symptoms started (month) | 1.57±1.0 | 2.34±2.0 | 0.209 |

| IgE (IU/L) | 10.9±12.4 | 161±500 | 0.442 |

| F2 (ku/l) | <0.35 | 0.43±1.3 | 0.309 |

| F1 (ku/l) | 2.0±6.6 | 0.04±0.13 | 0.223 |

| FX5 (ku/l) | 0.72±2.3 | 0.07±0.22 | 0.249 |

| Eosinophil percentage (%) | 5.8±3.5 | 5.6±5.2 | 0.929 |

| Provocation time (months) | 2.15±1.4 | 3.4±2.6 | 0.102 |

| Tolerance development time (months) | 5.07±1.2 | 10±2.0 | <0.001 |

| Complaints during exclusively breastfeeding n (%) | 14 (100%) | 20 (80%) | |

| None n (%) | 0 | 5 (20%) | 0.073 |

| Nutritional status when the symptoms started n (%) | |||

| Exclusively breastfed | 12 (85.7%) | 19 (76%) | 0.660 |

| Breastfed+complementary foods (2–4 meals/day) | 2 (14.3%) | 5 (20%) | |

| Breastfed+formula (2–4 meals/day)+complementary foods (1–3 meals/day) | 0 (2.6%) | 1 (4%) | |

| Formula (6–8 meals/day)+complementary foods (2–4 meals/day) | 0 (0%) | 4 (6.6%) | |

| Atopic disease history in the patient n (%) | 3 (21.4%) | 6 (24%) | 0.855 |

| Allergic disease history in the mother n (%) | 2 (14.3%) | 10 (40%) | 0.095 |

| Allergic disease history in the father n (%) | 4 (28.6%) | 10 (40%) | 0.475 |

| Allergic disease history in the siblings n (%) | 1 (7.1%) | 8 (32%) | 0.77 |

All patients admitted to the hospital with macroscopic bleeding in the stool. In addition, diarrhoea accompanied the symptoms in 89.6% (n=69), vomiting in 18% (n=14) and abdominal distension in 5% (n=4). Growth suspension was observed in 15.6% (n=12) patients. Massive bleeding was observed in 1.3% (n=1) patients (Table 3). This was the case for whom tolerance developed when 66 months old.

Descriptive data of patients with allergic proctocolitis.

| Gender (%) | |

| Male | 47 |

| Female | 53 |

| Starting age of symptoms (months) | 3.3±4.7 (0–36) |

| Offending food (%) | |

| Milk | 78 |

| Milk/egg | 13 |

| Egg | 5 |

| Multiple food allergy | 4 |

| Atopy in skin test (%) | 19.5 |

| Tolerance development time (months) | 14.7±11.9 (3–66) |

| Tolerance development age (%) | |

| 0–12 months | 40 |

| 13–24 months | 27 |

| 25–36 months | 9 |

| >36 months | 5 |

| Food allergy in the family (%) | 12 |

| Symptoms (%) | |

| Macroscopic blood in the stool sample | 10.4 |

| Macroscopic blood in the stool sample with diarrhoea | 89.6 |

| Vomiting | 18 |

| Growth suspension | 15.6 |

| Gross bleeding | 1.3 |

| GIS examination (%) | |

| Endoscopy | 5 |

| Colonoscopy | 6.5 |

| Hospitalisation (%) | 13 |

In 53% (n=41) of the patients, symptoms started while still being breastfed. The offending food was milk in 78% (n=60) of the patients, egg in 5% (n=4) milk and egg in 13% (n=10). Multiple food allergy was observed in three patients (Table 3). The other foods determined in addition to milk and egg were wheat with 3.9% (n=3), sesame with 2.6% (n=2), meat with 1.3% (n=1), fish with 1.3% (n=1), carrot with 1.3% (n=1) and apple with 1.3% (n=1). Three patients with multiple food allergies whose symptoms did not improve despite elimination were fed with aminoacid-based formula only; symptoms disappeared after aminoacid based formula. Supplementary foods were added to the diets of two patients after three months, after which multiple food allergy was diagnosed following the recurrence of symptoms with milk, egg, sesame and wheat in one and with milk, egg, fish and carrot in the other. Colonoscopy was performed on all these three patients with multiple food allergies, and histopathological evaluation of biopsy samples were found in accordance with FPIAP.

Other atopic propertiesThere was a family history of atopic diseases in 28.6% (n=22) and food allergy in 12% (n=9) of the cases (Table 3). Concomitant atopic dermatitis in 15.6% (n=12), recurring wheezing attacks in 6.5% (n=5), food anaphylaxis in 1.3% (n=1) and allergic rhinitis in 1.3% (n=1) of the patients were positive. In conclusion, there was an additional atopic disease in 24.7% of our cases.

Endoscopy and histologyColonoscopic evaluation demonstrated lymphoid nodular hyperplasia (LNH) and scattered erosions at rectum and sigmoid colon in 6.5% (n=5) of the patients. In these cases, histological examination revealed 15–50 eosinophils and degranulation in the eosinophils at 40× magnification in lamina propria. Gastroduodenoscopy was performed on 5% (n=4) of the patients and normal findings were observed (Table 3). Meckel scintigraphy was found negative in two patients with evident anaemia.

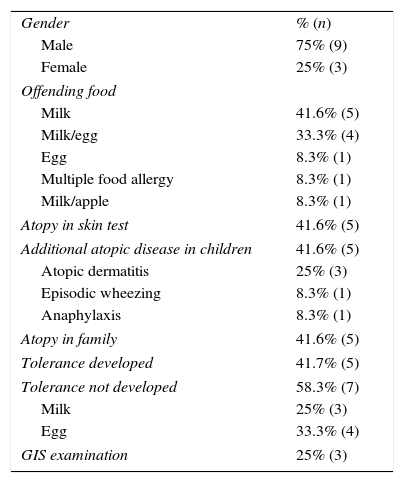

ToleranceMean tolerance development time of the patients was 14.77±11.98 months (minimum 3 and maximum 66 months). Tolerance developed before the age of one year in 40% (n=31), between the ages of 1–2 in 27% (n=21), between the ages of 2–3 in 9% (n=7) and after the age of three in 5% (n=4) of the patients (Table 3). Of the 12 cases persisting after the age of two, offending food was milk for five, milk and egg for four, egg for one, milk and apple for one whereas one had multiple food allergy (Table 4). Tolerance to milk developed earlier in patients for whom milk and egg were both offending foods.

Properties of the 12 cases who persisted after two years of age.

| Gender | % (n) |

| Male | 75% (9) |

| Female | 25% (3) |

| Offending food | |

| Milk | 41.6% (5) |

| Milk/egg | 33.3% (4) |

| Egg | 8.3% (1) |

| Multiple food allergy | 8.3% (1) |

| Milk/apple | 8.3% (1) |

| Atopy in skin test | 41.6% (5) |

| Additional atopic disease in children | 41.6% (5) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 25% (3) |

| Episodic wheezing | 8.3% (1) |

| Anaphylaxis | 8.3% (1) |

| Atopy in family | 41.6% (5) |

| Tolerance developed | 41.7% (5) |

| Tolerance not developed | 58.3% (7) |

| Milk | 25% (3) |

| Egg | 33.3% (4) |

| GIS examination | 25% (3) |

FPIAP development can be related with various foods. Cow's milk has been reported as the most common trigger.1,2,4 In previous studies, Lake et al.13 reported the offending foods as 65% milk, 19% egg, 6% corn and 3% soy and Lucarelli et al.14 reported as 50% milk, 28% egg, 14% rice, 7% wheat. We found in our patients that the offending food was milk for 78%, egg for 5%, milk and egg for 13%. In our study, three patients had multiple food allergies. Other foods that were determined very rarely were wheat, apple, carrot, meat, fish and sesame. The offending food for most of the persistent cases after the age of two was milk. Symptoms appeared during breastfeeding in 53% of the patients. Similar to our results, previous publications demonstrated that 60% of the cases were symptomatic during the breastfeeding period.2,4 FPIAP symptoms may occur during the first week of the life but rarely may come in view in the late childhood period.1,15 Ravelli et al.15 reported FPIAP due to cow's milk in 16 cases between the ages of 2–14 years that were persistent for more than six years with recurring rectal bleeding. Symptoms started for 27% (n=21) of our patients during the first month, for 13% (n=10) during 1–6 months and for one patient when 36 months old. Initiation of the symptoms during the first seven days of the life was encountered in 13% (n=10) of our patients. It has been reported that sensitisation during the intrauterine period may be the cause for patients who are symptomatic during the first week after birth.2,4 Rectal bleeding and diarrhoea were the two most common symptoms in our patients. Growth suspension, vomiting, stool with mucus were other accompanying symptoms. Rectal bleeding may be due to other aetiologies so differential diagnosis is important in these cases.4

Unfortunately, there is no specific test for diagnosis. The specificity and sensitivity of tests such as APT, specific IgE, SPT and endoscopic biopsies are low. The diagnosis is based on the improvement in gross bleeding of stool within 72–96h after the offending food is eliminated and the recurrence of symptoms in a few days with food challenge.4–6,8 However, occult blood can last longer. The skin prick test may give negative or inconsistent results if there is no accompanying atopic disease such as atopic dermatitis.4 In 15 of our patients, who had additional atopic findings such as atopic dermatitis, recurrent wheezing, anaphylaxis, the skin prick test was found positive. The diagnosis was verified via OFC carried out on the mother for 43% of our patients (n=33) who were symptomatic during breastfeeding without any supplementary food. APT is a test that can be used for the diagnosis of patients with delayed symptoms. However, inconsistency in the interpretation of the results and lack of standardisation for the method are disadvantages of this test.1,16 Lucarelli et al.14 reported positive result for 50% of the patients in APT with cows’ milk. In our study, APT with cow's milk was applied to only 12% of the patients, whose parents gave approval for the test, but positive result was observed in none of them. However, in the study of Lucarelli et al.,14 the patient group consisted of cases that had not benefited from the elimination diet. Endoscopic examination is not suggested for the diagnosis of FPIAP.2,17 However, endoscopic examination may help the diagnosis for patients with severe symptoms who do not respond to the elimination diet to exclude other aetiologies. Colonoscopic examination was carried out on 7% (n=5) of the patients with one gross bleeding and the others with no improvement in the symptoms despite elimination diet. Lymphoid nodular hyperplasia (LNH) and scattered erosions in the rectum and sigmoid were observed in these patients. 15–50 eosinophiles and degranulation in the eosinophils were observed at 40× magnification in the lamina propria in histological examination. Increased density of eosinophils in colonic mucosa, either in patients with LNH, was demonstrated in the previous studies. In our cases, raised colonic mucosal eosinophil density and presence of LNH were considered as consequences of food allergy.18,19 No consensus exists for diagnosis of eosinophilic colitis, although most authors have used a diagnostic threshold of 20 eosinophils per high-powerfield. Normal values for tissue eosinophils vary widely between different segments of the colon, ranging from <10 eosinophils per high-powerfield in the rectum to >30 in the cecum, so location of the biopsy is critically important for interpretation of findings.20 For this reason we considered 15 to 50 eosinophils as significant in patients with appropriate clinical pictures. Our results were compatible with the previous literature about endoscopic findings.2,4,14,20

The main treatment of FPIAP is the elimination of the offending food.4,8 Rectal bleeding generally improves during the 72nd–96th hour after the mother avoids the offending food. However, occult bleeding can last longer. Recurrent bleeding can be observed in some cases despite the elimination of the offending food.2,4–6,14,15 There is no treatment option other than elimination and no proper diet for non-IgE food allergies. Extensively hydrolysed formula (eHF) is suggested before aminoacid based formula.21 However, Lucarelli et al.14 preferred aminoacid-based formula in their study because of the residual immunological active proteins in eHF. We used aminoacid-based formula in 19.5% of our patients (n=15) and eHF in the remainder. Prognosis of FPIAP is good. Even though tolerance is developed during ages 1–3, publications and data about the prognosis are restricted. Lake et al.13 demonstrated that all patients older than one year of age developed tolerance. Lozinsky et al.1 reported that the OFC of 20% eosinophilic infants with colitis was positive after one year. As far as we know, there is no well-defined large group study that examines the prognosis of FPIAP. Tolerance developed in 14% (n=11) of the patients in our study after two years of age and the seven patients (9%) who did not develop tolerance even though they were older than two years of age are still under follow-up.

There was a history of food allergy in the families of 12% of the patients. One of the siblings of a patient has FPIAP. Although very rarely, FPIAP was reported previously in 1st degree relatives.22,23 These patients indicate the necessity of examining the genetic component of the disease.

The exact prevalence of FPIAP is unknown; the estimated prevalence ranges from 18% to 64% of the infants with rectal bleeding.1,24 Meyer et al.6 reported that over 40% of the children with non-IgE-mediated protein-induced gastrointestinal allergies have atopic eczema. Atopic dermatitis accompanied for 15.6% (n=12) of our patients. Similarly, various co-morbid IgE-mediated allergies such as asthma, rhinitis and frequent upper respiratory tract infections have been reported together with non-IgE-mediated allergies.6 For this reason, non-IgE-mediated allergies are thought to be multi-systemic disorders. Positive family history of atopy is present in up to 25% of infants with FPIAP.4 The accompanying symptoms were recurring wheezing attacks in 6.5% (n=5) of our patients, food anaphylaxia in 1.3% (n=1) and allergic rhinitis in 1.3% (n=1). There was a history of food allergy in the families of 12% (n=9) of the patients and a history of atopy (such as asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, drug allergy) in the families of 28.6% (n=22).

FPIAP predominantly affects the rectum and sigmoid colon. Prominent eosinophilic infiltrates are observed at the rectosigmoid mucosa in the patients. However, the pathogenic mechanisms that affect the eosinophilic inflammation in the colon are not exactly known.2,4,25 Ohtsuka et al.26 have recently demonstrated that CCL11 (eotaxin-1) mRNA and CXCL13 mRNA were highly expressed in the large-intestine mucosa of infants with FPIAP compared with control subjects. Delayed maturation of the intestinal flora in infants with rectal bleeding has been reported in recent years. Studies indicate that delayed maturation of the intestinal flora leads to insufficient induction of IgA and Treg cells.2 In conclusion, the pathogenesis of FPIAP is still not definitely known.2,17

In conclusion, FPIAP is a benign disease with excellent prognosis. However, unnecessary examinations and invasive procedures may be performed due to the anxiety of the clinicians and the family. Recovery generally occurs in one year, however it can also last longer in some cases. A longer follow up period is necessary according to our study. The most common offending food in our patients was milk. However, the offending food varies depending on the geographical region of residence and eating habits. When cases for which tolerance developed before and after one year of age were compared, it was determined that tolerance development was earlier for cases with an earlier starting age. Additionally, tolerance developed earlier in patients whose symptoms initiated during the breastfeeding period. It is thus hard to clearly argue that this result is related with only younger age or only breastfeeding. More studies are necessary in this subject.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Financial disclosureThe authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Authors’ contributionErdem Bahceci, Semiha: literature search, study design, data collection, manuscript preparation/editing, final manuscript approval.

Nacaroglu, Hikmet Tekin: literature search, study design, data collection, manuscript preparation/editing, final manuscript approval.

Karaman, Sait: literature search, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation.

Erdur, Cahit Barıs: literature search, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation.

Unsal Karkıner, Canan: literature search, manuscript preparation/editing, data analysis.

Can, Demet: literature search, manuscript preparation/editing, study design, final manuscript approval.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.