Background. It has been suggested that liver cirrhosis (LC), regardless of etiology, may be associated with anatomical cardiac alterations.

Objective. To describe the frequency and type of macroscopical anatomic cardiac abnormalities present in alcoholic and non-alcoholic cirrhotic patients in an autopsy series.

Material and methods. The autopsy records performed at our institution during a 12-year period (1990-2002) were reviewed. All cases with final diagnosis of LC were included, their demographic characteristics as well as cirrhosis etiology and macroscopic anatomical cardiac abnormalities (MACA) analyzed. Patients with any known history of heart disease prior to diagnosis of cirrhosis were excluded.

Results. A total of 1,176 autopsies were performed, of which 135 cases (11.5%) were patients with LC. Two patients with cardiac cirrhosis were excluded. Chronic alcohol abuse (29%) and chronic hepatitis due to hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (20%) were the most common causes of cirrhosis. The etiology was not identified in 35% of the cases, even after exhaustive clinical, serological and/or radiological assessment. In the postmortem analysis, 43% of the cases were informed to have MACA (47% in the group of patients with alcoholic cirrhosis and 41% in other types of cirrhosis); this rate increased to 62% in patients with ascites. The most frequent alterations were cardiomegaly and left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH).

Conclusion. The results confirm the high frequency of cardiac abnormalities in patients with cirrhosis, regardless of cirrhosis etiology.

In the past two decades, it has been suggested that liver cirrhosis (LC), regardless of its etiology, is associated with cardiovascular disorders: the existence of a “cirrhotic cardiomyopathy” (CCm) has been documented in the context of a normal or hyperdynamic circulatory state at rest.1–3

Kowalski, et al. were the first to report an increase in resting cardiac output and decreased systemic vascular resistance in patients with cirrhosis.4 Several hyperdynamic circulatory changes and alterations in ventricular contractility in response to stimuli were later described. Cardiac abnormalities were initially attributed to the cardio-toxic effects of alcohol; however, these alterations can also occur in patients with non-alcoholic liver cirrhosis.5

Anatomical and functional abnormalities in the heart of patients with LC in the absence of known cardiac disease have been described.4,5 Histological cardiac changes described in autopsy series of alcoholic patients, subsequently in non-alcoholic cirrhotic patients (NALC) and confirmed in experimental animal studies include: miocardial cell swelling and hypertrophy, interstitial fibrosis, nuclear vacuolation and an abnormal pigmentation due to the intracellular myocardial accumulation of lipofuscin. However, studies that directly deal with myocardial anatomical changes in patients with LC are scarce and they offer contradictory results: structural changes like left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) have been informed; other investigators have not found clinically relevant cardiovascular disease.6–10

ObjectiveThe purpose of this study was to describe the frequency and type of macroscopical anatomic cardiac abnormalities (MACA) present in alcoholic cirrhosis (ALC) and non-alcoholic cirrhosis in an autopsy series.

Material and MethodsWe reviewed all autopsy records of the Pathology Department at our institution (Hospital de Especialidades, Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI, IMSS, Mexico City), performed during January 1990 and December 2002. All patients with final diagnosis of LC were included, regardless of the cause of death. Patients with history of any known heart disease before the diagnosis of LC were excluded. The diagnosis of LC was established according to the criteria of the World Health Organization.11 General data as well as cirrhosis etiology were retrieved from medical history records and pathological findings.

To establish the etiology of cirrhosis we used the following criteria:

- •

Infection of hepatitis B virus (HBV) with the presence of positive surface antigen (HBsAg).

- •

Infection of hepatitis C virus (HCV) with the presence of Anti-HCV (from 1992) and/or positive viral load (RNA-HCV).

- •

Alcoholic etiology when documented history of significant alcohol consumption and negative au-toimmunity and HBV and HCV serum markers.

- •

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) when immunological markers (anti-mitochondrial, anti-nuclear and anti-smooth muscle antibodies) were positive.

- •

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) in the presence of cholestasis and diffuse multifocal intra and extrahepatic biliary track stenosis, and concentric fibrosis around bile ducts.12

- •

Secondary biliary cirrhosis (SBC) in the presence of chronic obstruction of extrahepatic bile duct.

The diagnosis of cryptogenic cirrhosis was rendered when either by the clinical history and/or laboratory studies we were unable to identify the cause of LC.

Demographic data, clinical history, cause of hospitalization, outcome and progress to death obtained from the autopsy record and protocol. Also recorded were the results of laboratory tests, description of the external and internal postmortem examination, measurement and registration of heart weight and presence/absence of ascites, description of internal organs and systems and the macroscopic and microscopic pathologic diagnoses.

Cardiomegaly was established when heart weight was greater than 300 g, left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) when the average thickness of left ventricle was higher than 1 cm, right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH) when the average thickness of the right ventricle was greater than 0.3 cm, valvular heart disease when the valve diameter (measured at the valvular ring) or its morphology were altered;13 pericardial effusion when pericardial fluid more than 50 mL was found in pericardial sac; pleural effusion or hydrothorax when fluid more than 15 mL was found in right or left pleura. Ascites in the presence of free fluid in the abdominal cavity more than 25 mL.14

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics were used for the analysis of the demographic and clinical characteristics. The results are expressed as median (range), mean (± SD) and proportions. Qualitative variables were assessed using Chi-square test. The comparison of quantitative parameters was performed using parametric or nonparametric tests according to data distribution. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

ResultsA total of 1,176 autopsies were performed during a12-year period at our institution, in 135 cases (11.5%) the final diagnosis of LC was established. We excluded 2 patients with diagnosis of cardiac cirrhosis. One-hundred and thirty-three patients (68 men and 65 women), with a mean age of 55.2 years (± 14.9) were the core of our study. The etiologies of cirrhosis were:

- •

Alcoholic (29%).

- •

Viral (23%).

- •

Autoimmune diseases:

- º

PBC (4%).

- º

PSC (3%).

- º

AIH (2%).

- º

SBC (4%).

- º

35% of cases were classified as cryptogenic cirrhosis. In 10 cases, dead occurred between 1990 and 1992, when HCV serology was still not available. In 60% of the cases, we found anatomical evidence of portal hypertension (esophageal and/or gastric varices, ascites and/or hydrothorax) (Table 1).

Demographic and clinical characteristics by cirrhosis etiology.

| Autopsy findings | ALC | NALC | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 38 (100%) | N = 95 (100%) | ||

| • Gender: Male/Female | 33/5 | 35/60 | < 0.01 |

| • Age (years ± SD) | 55 ± 11.5 | 55 ± 16.1 | ns |

| • Normal heart | 20 (53) | 56 (59) | ns |

| • Macroscopic anatomical cardiac abnormalities | 18 (47) | 39 (41) | ns |

| º Cardiomegaly | 11 (29) | 24 (25) | ns |

| º Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) | 5 (13) | 12 (13) | ns |

| º Bi-ventricular hypertrophy (BVH) | 2 (5) | 11 (12) | ns |

| º Right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH) | 1 (3) | 2 (2) | ns |

| º Valvulopathy | 4 (11) | 5 (5) | ns |

| º Other: pericardial effusion, pericarditis, ischemic | 1 (3) | 7 (7) | ns |

| • Ascites | 15 (39) | 38 (40) | ns |

| • Hydrothorax | 4 (11) | 9 (9) | ns |

| • Esophageal and/or gastric varices | 34 (89) | 46 (48) | < 0.01 |

ALC: Alcoholic liver cirrosis. NALC: Non-Alcoholic liver cirrhosis. SD: Standard deviation.

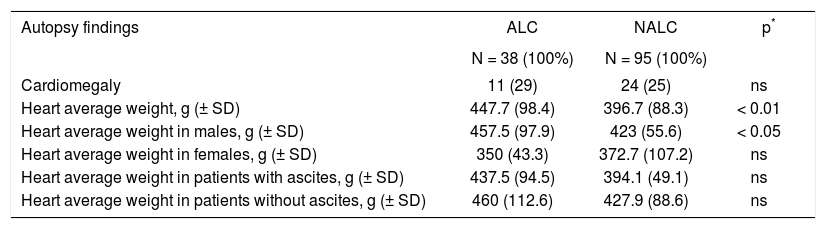

MACA were found in 43% of the cases, the most frequent findings were cardiomegaly and ventricular hypertrophy which presented with similar frequency regardless of the etiology of cirrhosis (Table 2). Cardiomegaly was documented in 26.3% of cirrhotics, with an average weight of 414.2 g (± 93.6). When comparing groups, we found that the average weight was higher in ALC with 447.7 g (± 98.4) vs. 396.7 g (± 88.3) in the group of non-alcoholic cirrhosis (p < 0.01), and this difference was preserved in men, when assessing by gender (Table 3).

Characteristics of the population with and without ascites.

| Autopsy findings | Ascitis | Without ascitis | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 53 (100%) | N = 80 (100%) | ||

| • Gender: Male/Female | 28/25 | 40/40 | ns |

| • Age (years ± SD) | ns | ||

| • Alcoholic cirrhosis | 15 (28) | 23 (29) | ns |

| • No alcoholic cirrhosis | 38 (72) | 57 (71) | ns |

| • Normal heart | 20 (38) | 56 (70) | < 0.05 |

| • Macroscopic anatomical cardiac abnormalities | 33 (62) | 24 (30) | < 0.05 |

| º Cardiomegaly | 23 (43) | 12 (15) | < 0.05 |

| º Left Ventricular Hypertrophy | 11 (21) | 6 (8) | < 0.05 |

| º Bi-ventricular Hypertrophy | 9 (17) | 4 (5) | < 0.05 |

| º Right Ventricular Hypertrophy | 2 (4) | 1 (1) | ns |

| º Valvulopathy | 5 (9) | 4 (5) | ns |

| º Other: effusion, pericarditis, ischemic cardiopathy | 4 (8) | 4 (5) | ns |

SD: Standard deviation.

Cardiomegaly and heart weight by gender and cirrhosis etiology.

| Autopsy findings | ALC | NALC | p* |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 38 (100%) | N = 95 (100%) | ||

| Cardiomegaly | 11 (29) | 24 (25) | ns |

| Heart average weight, g (± SD) | 447.7 (98.4) | 396.7 (88.3) | < 0.01 |

| Heart average weight in males, g (± SD) | 457.5 (97.9) | 423 (55.6) | < 0.05 |

| Heart average weight in females, g (± SD) | 350 (43.3) | 372.7 (107.2) | ns |

| Heart average weight in patients with ascites, g (± SD) | 437.5 (94.5) | 394.1 (49.1) | ns |

| Heart average weight in patients without ascites, g (± SD) | 460 (112.6) | 427.9 (88.6) | ns |

ALC: Alcoholic liver cirrosis. NATC: Non-alcoholic liver cirrosis. SD: Standard deviation.

In the group of patients with ascites, irrespective of etiology, 62% had cardiac abnormalities, most often cardiomegaly and LVH (Table 2). Also, the heart’s average weight was similar between the groups (Table 3). Comparing the heart average weight by decades in patients with cardiomegaly we found that weight tended to be higher in the 5th decade, with an average weight of 455g (± 148.6), without a significant difference by etiology (Table 4).

Heart weight by age and cirrhosis etiology.

| Age | LC | ALC | NALC | P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (± SD) | N=35 | N= 11 | N= 24 | |

| 39 or less (± SD) | 412.5 (17.68) | - | 412.5 (17.68) | - |

| 40 to 49 (± SD) | 455 (148.6) | 487.5 (194.5) | 390 (28.3) | ns |

| 50 to 59 (± SD) | 417.2 (49.2) | 431.25 (37.5) | 406 (58.6) | ns |

| 60 to 69 (± SD) | 417.3 (97.65) | 445 (112.4) | 394.2 (86.98) | ns |

| 70 to 79 (± SD) | 402.9 (120.2) | - | 402.9 (120.2) | - |

| 80 or more (± SD) | 435 (120.2) | - | 435 (120.2) | - |

LC: Liver cirrosis. ALC: Alcoholic liver cirrhosis. NALC: Non-alcoholic liver cirrhosis. SD: Standard deviation.

The results of this study confirm that myocardial alterations are common in patients with cirrhosis and that its development is mainly related to the degree of liver failure, rather than the cirrhosis etiology.1,2

In Mexico, cirrhosis is currently the most prevalent chronic liver disease, the main causes according to a previous report in 2004 by Mendez-Sanchez, et al.15 are alcohol (39.5%), followed by hepatitis C (36.6%) and unknown cause (10.4%). These etiologies although consistent with those of our study, differ in the percentages.

Hall, et al.16 evaluated 16.600 autopsies; in 782 (4.7%) the final diagnosis was LC, with 90% of the cases being of alcoholic etiology, and heart failure representing the cause of death in 15%, only a slightly lower mortality than that caused by bleeding or infection in this group of patients. However, the clinical relevance of the cardiac abnormalities in patients with LC is still unknown.

Kowalski, et al. were the first to report an increase in resting cardiac output and decreased systemic vascular resistance in patients with cirr-hosis.4 However, despite the hyperdynamic circulation, impaired ventricular contractility in response to stimuli was described in cirrhotic patients. These findings were initially attributed to alcohol toxicity. In the last two decades, cirrhosis has been associated with a wide spectrum of cardiovascular disorders.5

In the mid 1980’s, studies in experimental animals models and in nonalcoholic patients showed heart contractility abnormalities.17 These clinical and experimental findings led to the introduction of a new clinical entity defined as cirrhotic cardiomyopathy (CCm): normal or hyperdynamic circulatory state at rest, systolic and diastolic dysfunction and electrophysiological abnormalities in the absence of other known cardiac disease.6–8

In our study we found that 11.5% of the population had a final diagnosis of LC, higher than previously reported4 and 43% of the cirrhotic population had significant MACA. Cardiomegaly and ventricular hypertrophy were the most common anatomic abnormalities; cardiomegaly was present in 26.3% of cirrhotics, independent of etiology, with an average weight of 414.2 g. When comparing by groups we found that the average weight was higher in alcoholic cirrhosis, preserving the variations in males. Ventricular hypertrophy was present in 26% and LVH was the most frequent (13.5%), similar to that described by Lunseth, et al.,10 who evaluated autopsies of 108 cirrhotic individuals including all etiologies, finding significant heart disease in 48% of the population: 48% of men and 24% of women had car-diomegaly and 32.4% showed cardiac hypertrophy.

After evaluating the group of patients with ascites, we noted that 62% of patients had significant MACA, with predominance of cardiomegaly and ventricular hypertrophy, independent of the cause of cirrhosis, suggesting that cardiomyopathy is more likely to develop at an advanced state of liver function loss. However, when comparing the heart average weight between the groups with and without ascites, we observed no significant difference. It has been postulated that myocardial hypertrophy may be an adaptive response to overload caused by hyperdynamic circulation and hormonal trophic effects. On the other hand, diastolic abnormalities could be related to mechanical factors such as tense ascites increasing intrathoracic pressure, although the main mechanism impairing diastolic function seems to be a net gain in cardiac mass by hypertrophy and/or left ventricular fibrosis.1 Diastolic dysfunction is mainly observed in patients with ascites, and its severity is related to the degree of liver failure and portal hypertension.17,18

It has been considered that CCm conditions a latent diastolic dysfunction status, resulting in a clinically manifest disease by physiological or pharmacological stress, bacterial infections (spontaneous bacterial peritonitis) placement of intrahepatic porto-systemic shunts (TIPS-transyugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt) or liver trans-plantation.7

Among the limitations of this retrospective study are:

- •

The impossibility of identifying the etiology of cirrhosis in 35% of the cases, classified as “cryptogenic” due to insufficient information concerning medical history and after exhaustive clinical, serological and/or radiological assessment.

- •

A possible selection bias of patients at our institution as referral center, that may not be representative of the general population.

- •

The fact it is based upon autopsy records, could somehow reflect the state of severity and impairment of liver function and as a result, overestimate the frequency of MACA.

A disadvantage with this type cardiomyopathy as nosologic entity is the lack of strict criteria for its diagnosis,7 so this syndrome is not commonly recognized; the presence of cardiomyopathy should be suspected in patients with worsening hemodynamics, and can benefit from a more aggressive surveillance and management of the underlying cause of hepatic failure, particularly if they are to be submitted to procedures such as TIPS, large volume paracentesis or liver transplantation.6,19

ConclusionOur study confirms the high frequency of MACA in patients with cirrhosis regardless of the etiology. Prospective studies are needed to assess the structural, electrophysiological and pharmacological stress changes related to CCm.

Abbreviations- •

AIH: Autoimmune hepatitis.

- •

ALC: Alcoholic liver cirrhosis.

- •

CCm: Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy.

- •

CI: Cardiac index.

- •

GC: Cardiac output.

- •

HBV: Hepatitis B virus.

- •

HCV: Hepatitis C virus.

- •

LC: Liver cirrhosis.

- •

MACA: Macroscopic anatomical cardiac abnormalities.

- •

NALC: Non-alcoholic liver cirrhosis.

- •

PBC: Primary biliary cirrhosis.

- •

PSC: Primary sclerosing cholangitis.

- •

SD: Standard deviation.

- •

LVH: Left ventricular hypertrophy.

- •

RVH: Right ventricular hypertrophy.

- •

TIPS: Transyugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt.

- •

SVR: Systemic vascular resistance.

Nayeli X. Ortiz-Olvera, Guillermo Castellanos-Pallares, Luz M. Gómez-Jiménez, María L. Cabrera-Muñoz, Jorge Méndez-Navarro, Segundo Morán-Villota, Margarita Dehesa-Violante have nothing to disclosure.