Relapsing polychondritis is an immune-mediated disease associated with inflammation in cartilaginous structures and other tissues throughout the body, particularly the ears, nose, eyes, joints, and respiratory tract. Although association with other conditions is seen in about one-third of the cases, liver involvement is not usually observed in those patients. We described a case of liver involvement in relapsing polychon-dritis, presenting with a predominantly cholestatic pattern. Other conditions associated with abnormal liver tests were excluded and the patient showed a prompt response to steroid therapy. We discuss the spectrum of the liver involvement in relapsing and review the literature.

Relapsing polychondritis (RPC) is an immune-mediated condition associated with inflammation in cartilaginous structures and other tissues throughout the body, particularly the ears, nose, eyes, joints, and respiratory tract.1 Other proteoglycan-rich structures, such as the inner ear, eyes, blood vessels, heart, and kidneys may be involved.1 Although histological changes and nonspecific laboratory findings may be of value, RPC diagnosis remains largely clinical. Empirically derived diagnostic criteria have been used to define relapsing po-lychondritis.2 Even though around 30% of RPC cases are associated with other diseases especially systemic vasculitis or myelodysplastic syndrome,3 liver involvement is not well documented, especially as the first manifestation of RPC.

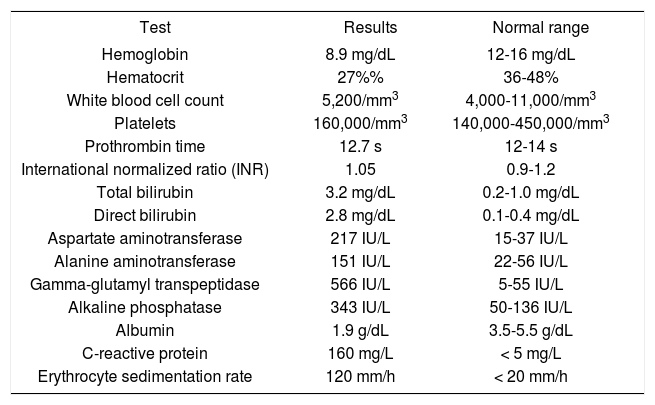

Case ReportA 48-year-old woman was admitted with a 20 days history of asthenia, loss of appetite and low grade fever. Five days before the admission, she also developed jaundice, choluria, conjunctival hyperemia, eyelid swelling and arthralgia. She had no complaints of abdominal pain or pruritus as well as no past history of alcohol consumption, exposure to he-patotoxic drugs or other comorbidities. On examination, she was jaundiced and had bilateral wrist and ankle arthritis, as well as bilateral conjunctivitis. The liver was palpable 2 cm below the right costal margin, but the spleen was not enlarged. Laboratory evaluation on admission (Table 1) revealed a hematocrit of 27%, platelets 160,000/mm3, total leukocytes 5,200/mm3, total bilirubin 3.2 mg/dL (direct fraction 2.8 mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase 217 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase 151 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 343 IU/L, gamma-glutamyl transpepti-dase 566 IU/L, and INR 1.05. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 120 mm (in the first hour) and the C-reactive protein was 160 mg/L. HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C serologies were negative. Antinuclear, anti-smooth muscle and antimitochondrial antibodies were also negative. Patient underwent extensive evaluation for bacterial infection, including blood and urine cultures, transesophageal echocardiogram, abdominal and thoracic computerized tomography. No indication of systemic infection was observed and no empiric antibiotics were given. An ultrasonography of the liver and bile ducts was also unremarkable.

Main laboratory findings at admission.

| Test | Results | Normal range |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | 8.9 mg/dL | 12-16 mg/dL |

| Hematocrit | 27%% | 36-48% |

| White blood cell count | 5,200/mm3 | 4,000-11,000/mm3 |

| Platelets | 160,000/mm3 | 140,000-450,000/mm3 |

| Prothrombin time | 12.7 s | 12-14 s |

| International normalized ratio (INR) | 1.05 | 0.9-1.2 |

| Total bilirubin | 3.2 mg/dL | 0.2-1.0 mg/dL |

| Direct bilirubin | 2.8 mg/dL | 0.1-0.4 mg/dL |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 217 IU/L | 15-37 IU/L |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 151 IU/L | 22-56 IU/L |

| Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase | 566 IU/L | 5-55 IU/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 343 IU/L | 50-136 IU/L |

| Albumin | 1.9 g/dL | 3.5-5.5 g/dL |

| C-reactive protein | 160 mg/L | < 5 mg/L |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 120 mm/h | < 20 mm/h |

Liver biopsy (Figure 1) showed general hepatic architecture well preserved, with minimal parenchy-mal changes, portal tracts with scarce mononuclear inflammatory cells and changes of biliary pattern with mild fibrosis. These findings were not sufficient to suggest the diagnosis and there were no histolo-gical markers consistent with primary biliary cirrhosis or autoimmune hepatitis.

Liver biopsy showing general hepatic architecture well preserved with minimal parenchymal changes (A). Portal tracts showed scarce mononuclear inflammatory cells (B) and changes of biliary pattern with mild fibrosis (C). Figure D exhibit detail of the portal tract showing edema and mild ductular proliferation intermingled with some mononuclear inflammatory cells and scarce neutrophils.

During the investigation, the patient developed bilateral external ear and nasal cartilage progressive inflammation, hearing impairment, tinnitus and vertigo. Based on the clinical findings, the diagnosis of RPC was made and oral prednisone was started at 1 mg/kg/day. A significant clinical improvement was observed and a complete normalization of aminotransferase, bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels was achieved within 15 days of treatment.

DiscussionA large number of systemic inflammatory disorders can affect the liver, with variable prevalence and intensity.4 The recognition of these manifestations is essential in managing these patients, who also have abnormal liver tests commonly as a result of hepatotoxicity by various classes of drugs. In addition, differential diagnosis with other primary liver diseases such as autoimmune hepatitis and primary biliary cirrhosis is important. In this regard, hepatic histological evaluation can provide important information. Nonspecific histological findings have been described in several autoimmune diseases including lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis.4-5

The liver involvement in RPC is only anecdotally reported. In 1983, Islam, et al. described the association between RPC and cryptogenic cirrhosis in a 37-year-old male.6 Even though there was histologi-cal confirmation of cirrhosis, a more detailed etiolo-gic investigation of the liver disease was lacking. In addition, this report antedated the discovery of hepatitis C virus, recognized over the last few years as a significant cause of liver disease worldwide.7 In fact, more recently, the association between RPC, chronic hepatitis C virus infection and mixed cryog-lobulemia was reported.8 In this case, a 74-year-old woman presented with RPC-related symptoms several months before the diagnosis of hepatitis C and mixed cryoglobulinemia syndrome. Interestingly, suppression of HCV viremia during interferon therapy was associated with remission of RPC, suggesting a role of HCV in RPC pathogenesis in this report.

In the present case, biochemical findings suggested a predominantly cholestatic pattern. A thorough investigation could not identify any alternative explanation for the liver abnormalities found, and a presumptive diagnosis of RPC-related liver injury was made. There was no history of exposure to drugs with recognized association with cholestatic toxic liver injury, and other causes of liver disease have been carefully excluded. An overlap with a primary cholestatic liver disease has also been considered as an alternative diagnosis, since one case report of the association between RPC, Churg-Strauss vasculitis and PBC has already been described.9 However, in the present case, typical features of these disorders such as nonsuppurative destructive cholangitis on liver biopsy and AMA were absent. Similarly, the association with autoimmune hepatitis was considered unlikely in the present case, since no histological or serological evidence of this condi-tion was observed.10

In summary, RPC is a rare and difficult to diagnose condition, which exhibits a variety of nonspecific manifestations. Although apparently uncommon, liver involvement can be observed in patients with RPC, and may even be the initial manifestation of this disease.

Conflicts of InterestThere are no conflicts of interest related to the manuscript. Nothing to report.