Background and aims. Entecavir (ETV) is effective and safe in patients with chronic hepatitis B in the short term, but its long term efficacy and safety has not been established.

Material and methods. We evaluated HBV DNA clearance, HBeAg/antiHBe and HBsAg/antiHBs seroconversion rates in HBeAg-positive and negative NUC naïve HBV patients treated with ETV for more than 6 months, and predictors of response.

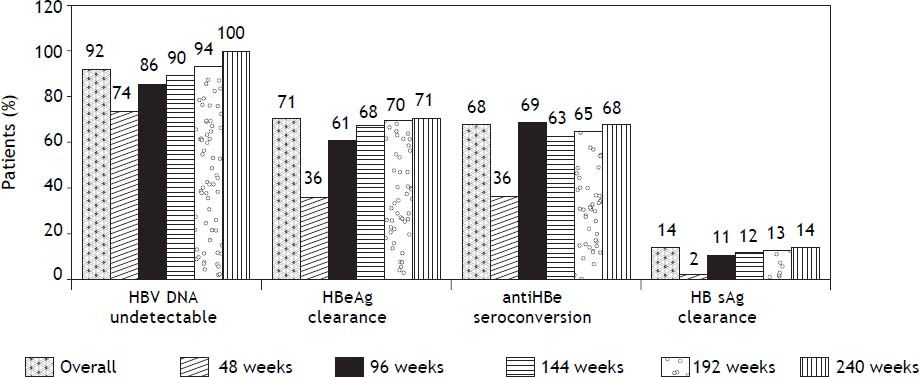

Results. A hundred and sixty nine consecutive patients were treated with ETV for a median of 181 weeks. 61% were HBeAg positive, 23% were cirrhotics, and mean HBV-DNA levels were 6,88 ± 1,74 log10 lU/mL. Overall, 156 (92%) patients became HBV DNA undetectable, 92 (88%) HBeAg positive and 64 (98%) HBeAg negative patients. Seventy four (71%) patients cleared HBeAg after a median of 48 weeks of treatment, 23 (14%) patients cleared HBsAg (19 HBeAg positive and 4 HBeAg negative, p 0.025) after a median of 96 weeks of treatment, and 22 (13%) patients developed protective titers of anti-HBs. At the end of the study, 35 (20%) patients had discontinued therapy: 33 HBeAg positive and 2 HBeAg negative; 9 of them (26%) developed virological relapse after a median of 48 weeks of stopping treatment. None of the patients had primary non response and one patient developed breakthrough. Two patients developed HCC, three underwent liver transplantation and 3 deaths were attributable to liver-related events. No serious adverse events were reported.

Conclusion. Long term ETV treatment showed high virological response rates, and a favorable safety profile for NUC-naive HBeAg-positive and negative patients treated in clinical practice.

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) is estimated to have infected more than 2 billion people worldwide, of whom 400 million are chronically infected today and are at an increased risk of liver-related complications, including cirrhosis, liver failure, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and death.1,2 In most regions of America, HBV prevalence is relatively low, with hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity ranging from < 2 to 7% compared with Asia, Africa and the Middle East, where HBV prevalence rates reach 5-20% of the general population.2,3

Indications for treatment have been established by several international guidelines. Pegylated interferon α (PEG-IFN α), tenofovir (TDF) and entecavir (ETV) had been selected as the first-line therapy to initiate treatment in naïve chronic HBV infected patients.3,4 Treatment end-points are complete viral suppression (undetectable levels of HBV DNA replication), HBeAg clearance and seroconversion in hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-positive patients, and if possible HBsAg clearance and development of anti-HBs antibody.3,4 Patients achieving these serologic end-points may discontinue treatment, after an additional 6-12 months period of consolidation therapy, according to the cited guidelines. In HBeAg negative patients, duration of treatment is not clear; it should be continued until HBsAg clearance is achieved.

ETV is a potent inhibitor of HBV replication, which is commercially available since 2005. In phase III randomized clinical trials (RCT) entecavir at a dose of 0.5 mg/day in treatment-naïve patients suppressed HBV DNA to undetectable levels by year one in 67% of HBeAg-positive and in 90% of HBeAgnegative patients.5,6 Recent reports showed that when administered for 2 to 5 years, resulted in a better HBV DNA suppression and higher rates of HBeAg seroconversion.7,8 It has a high genetic barrier to resistance and a strong resistance profile in treatment naïve patients, but genotypic resistance is higher in patients previously treated with lamivudine. Recently reported results of more than 6 years of therapy showed that in nucleos(t)ide-naive patients, the cumulative probability of genotypic resistance to ETV was 1.2%.9 Also, ETV treatment have shown that it can improve fibrosis of the liver and can cause fibrosis and cirrhosis regression.10

Most results from studies in routine clinical practice performed in Europe and Asia, including more than 1,500 treated patients, reported similar rates of virologic and serologic responses than those described in clinical trials,11–20 although others showed lower response rates.21,22 The aim of the present study is to evaluate the efficacy and safety of long term ETV treatment in chronic HBV NUC-naïve HBeAg positive and negative patients in routine clinical practice in our country.

Material and MethodsStudy populationWe included 169 patients with chronic HBV treated with ETV 0.5 mg/day for at least 6 months in 8 centres in Argentina. Each centre included all patients treated since January 2005. We report our virologic and serological results with continued treatment up to March 1st 2013 or until discontinuing ETV, according to international recommended stopping rules. We evaluated the effect of ETV treat- ment on HBV DNA clearance, HBeAg loss, antiHBe seroconversion, HBsAg loss, antiHBs seroconversion and virologic relapse rates. We also evaluated the influence of baseline demographic characteristics, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) values (mean and ≥ 5 times upper limit of normal-ULN), HBV DNA values (mean and ≥ 7 log10 IU/mL), Metavir activity (A) and fibrosis (F) scores; and presence of cirrhosis on serologic and virologic response rates. Treatment duration was defined according to current stopping rule guidelines: discontinuation after 24 to 48 weeks of antiHBe seroconversion in HBeAg positive patients and indefinitely in HBeAg negative/antiHBe positive patients.3,4 At baseline and at a 6-month interval the following parameters were recorded in patients receiving treatment or after its discontinuation: liver functional tests, cellular blood counts, serum HBV DNA levels; HBsAg, antiHBs, HBeAg and antiHBe status.

Patients older than 18 years; HBV DNA positive; HBeAg positive or negative; and treatment naïve were included. We excluded patients treated in RCTs; HIV and/or HCV coinfection; solid organ transplantation; on hemodialysis or with other associated liver disease. Data was obtained from medical records, and anonymously entered in a database.

Laboratory testingDiagnosis of chronic hepatitis B was defined as a positive serum HBsAg and detectable HBV-DNA for more than six months, independent of ALT levels and HBeAg status. Quantitative HBV DNA was determined by Cobas Taqman HBV Real Time PCR test (Roche Molecular systems Inc.-Branchburg, NJ, USA) with a limit of detection of 6 IU/mL (0.78 log). HBsAg, antiHBs, HBeAg, antiHBe and antiHBc were assessed by Microparticule Enzyme Immunoassay assay (MEIA) (Abbott Diagnostics DivisionGermany). In case of virological breakthrough, ETV resistance was evaluated by direct sequencing of the viral genome. HBV genotypes were not evaluated. The diagnosis of liver cirrhosis was based on liver biopsy, imaging studies or clinical and biochemical parameters.

Treatment was indicated and monitored according to national and international guidelines. In some cases, doses might be different to those recommended, according to individual medical judgment. Management of adverse events (AEs), including dose modifications or treatment suspension was decided by the treating physicians according to national and international guidelines and to their own clinical judgment. The protocol was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Centro de Educación Médica e Investigaciones Clínicas Norberto Quirno “CEMIC”.

Statistical analysisMicrosoft Excel 2007® software (Microsoft, Seattle, WA, USA) was used for the database. STATA® statistical software was used for the analysis (version 11.1 Stata Corporation, Tx., USA). The chi-square test and Fisher exact test were employed to compare categorical variables, and continuous variables were compared using the t-test and Mann-Whitney U test. Cox proportional hazard model and Kaplan-Meier method were used to explore base-line factors predicting a virologic response. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

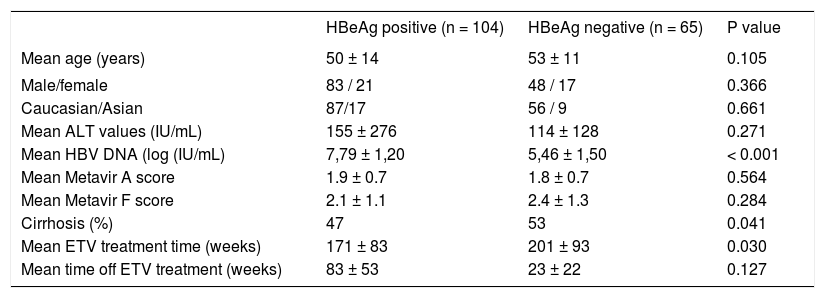

ResultsWe performed a retrospective, longitudinal study in a cohort of 169 prospectively followed chronic HBV naïve HBeAg positive and negative patients. One hundred and thirty one patients (77%) were male, 143 (85%) were Caucasian and 25 (15%) were Asians, with a mean age of 51 ±13 years. One hundred and four patients (61%) were HBeAg positive with a mean viral load of 6.88 ± 1.81 log10 IU/mL. ALT was elevated in 149 patients (89%) before treatment, with a mean value of 139 ± 231 IU/mL. One hundred and thirteen patients (71%) underwent a liver biopsy: mean Metavir A score was 1.92 ± 0.76 and mean F score was 2.26 ± 1.21; 38 patients (23%) had cirrhosis and 11 had decompensated cirrhosis before treatment. HBeAg positive patients have higher HBV DNA values, had been treated for a shorter period of time, and had a lower incidence of cirrhosis than HBeAg negative ones. Age, gender, race, baseline ALT values, mean fibrosis scores and off treatment period of time were similar in both HBeAg positive and negative patients (Table 1).

Baseline demographics characteristics of the overall population according to HBeAg status.

| HBeAg positive (n = 104) | HBeAg negative (n = 65) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 50 ± 14 | 53 ± 11 | 0.105 |

| Male/female | 83 / 21 | 48 / 17 | 0.366 |

| Caucasian/Asian | 87/17 | 56 / 9 | 0.661 |

| Mean ALT values (IU/mL) | 155 ± 276 | 114 ± 128 | 0.271 |

| Mean HBV DNA (log (IU/mL) | 7,79 ± 1,20 | 5,46 ± 1,50 | < 0.001 |

| Mean Metavir A score | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 0.564 |

| Mean Metavir F score | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 0.284 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 47 | 53 | 0.041 |

| Mean ETV treatment time (weeks) | 171 ± 83 | 201 ± 93 | 0.030 |

| Mean time off ETV treatment (weeks) | 83 ± 53 | 23 ± 22 | 0.127 |

Median ETV treatment period was 181 weeks (25-75th percentile, 108-248 weeks): 165 (98%), 135 (80%), 105 (62%), 80 (47%), 47 (28%) and 28 (16%) patients were treated for 48, 96, 144, 192, 240, and 288 or more weeks, respectively. Treatment doses were not modified during therapy.

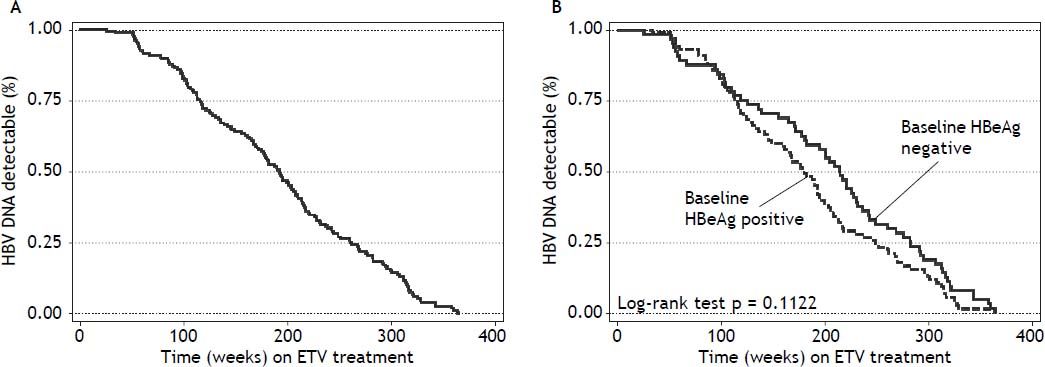

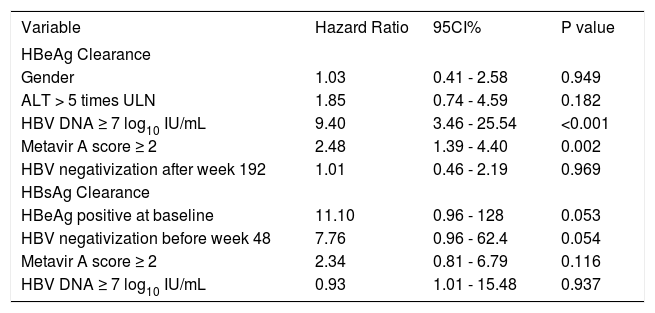

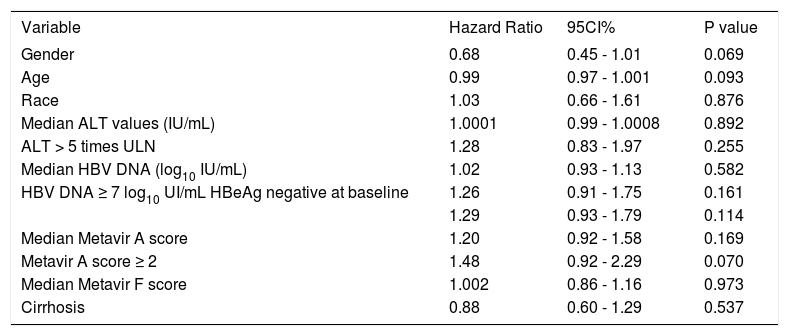

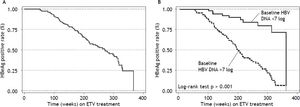

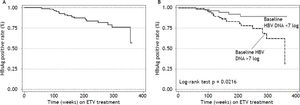

Virologic responseOverall, 156 (92%) patients became HBV DNA undetectable (Figure 1). In HBeAg positive patients, 92 (88%) became HBV DNA undetectable; with 83, 85, 89 and 100% on-treatment response rates at 96, 144, 192 and 240 weeks, respectively. In HBeAg negative patients, 64 (98%) became HBV DNA undetectable; with 91, 95, and 100% on-treatment response rates at 96, 144, and 192 weeks, respectively. Figure 2A shows the cumulative clearance of HBV DNA calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method. None of the patients had primary non response and one patient developed breakthrough (M204V, S202G).

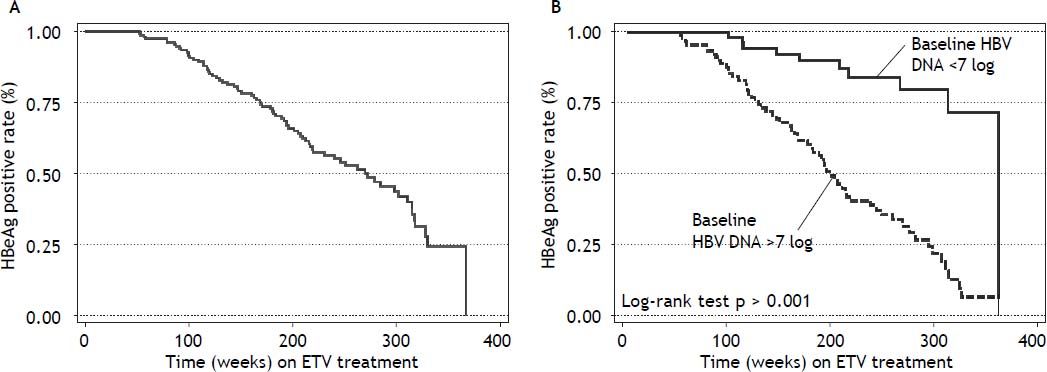

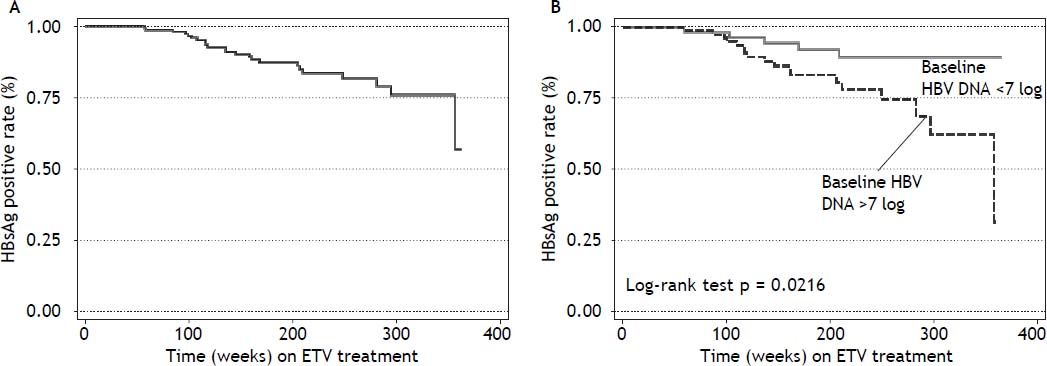

Seventy four (71%) patients became HBeAg negative and 71 (68%) antiHBe positive, after a median of 48 weeks (25-75th percentile, 48-96 weeks) of treatment; 23 (14%) patients became HBsAg negative and 22 (13%) antiHBs positive, after a median of 96 weeks (25-75th percentile, 72-96 weeks) of treatment (Figure 1); figure 3A shows the cumulative clearance of HBeAg calculated with the KaplanMeier method. Twenty three (14%) patients cleared HBsAg (19 HBeAg positive and 4 HBeAg negative, p 0.025) and 22 (13%) patients developed protective titers of anti-HBs (Figure 1); figure 4A shows the cumulative clearance of HBsAg calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method.

At the end of the study, 36 patients discontinued treatment. One due to breakthrough associated to an ETV resistant variant (M204V, S202G), and 35 (20%) due to sustained virologic response; 33 of these patients developed HBeAg/antiHBe seroconversion and 18 HBsAg/antiHBs seroconversion. Median off treatment time was 66 weeks (25-75th percentile, 33- 128 weeks). Nine patients (26%), all HBeAg positives at baseline, developed HBV DNA relapse after a median of 48 weeks (25-75th percentile, 23-77 weeks) off treatment, 3 of them showed HBeAg reversion and 4 antiHBe lost. None of HBsAg/antiHBs seroconverters relapsed.

Clinical outcomesOf the 169 treated patients, 38 (23%) had cirrhosis and 11 had decompensated cirrhosis before treatment. During the study period two patients developed HCC and three underwent liver transplantation. Three deaths were attributable to liver-related events: 2 patients with decompensated liver disease before treatment developed liver failure and died (one after transplantation) and the other due to HCC; all 3 patients were HBV DNA undetectable at the time of death. The other 9 decompensated cirrhotic patients recovered liver function with treatment. No serious adverse events were reported.

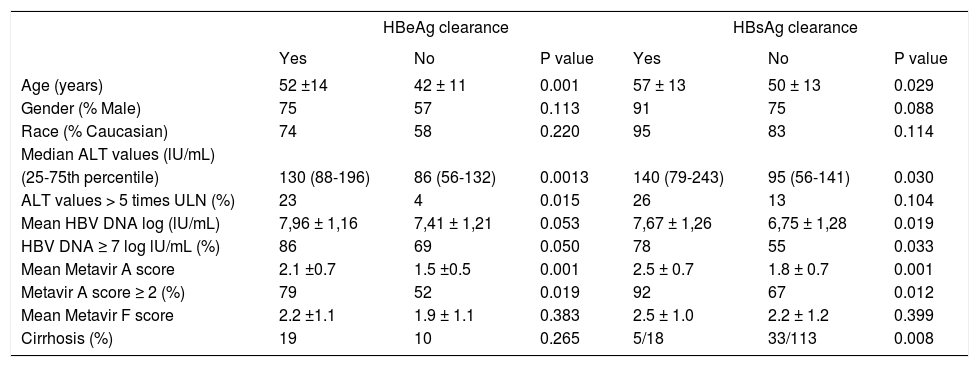

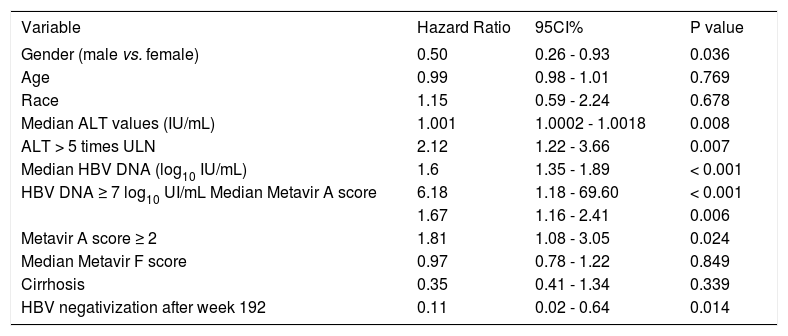

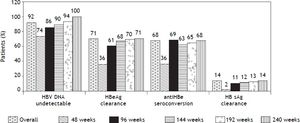

Predictive factors of serologic and virologic responsesWe have evaluated if any of baseline demographic characteristics and on treatment response were associated with serologic response. When evaluating baseline parameters, patients achieving HBeAg clearance were older, have higher Metavir A scores, and ALT and HBV DNA values at baseline than non-responders (Table 2). We evaluated if any of these characteristics predicted HBeAg response. In the univariate analysis male gender (HR: 0.50, 95% CI 0.26-0.93, p = 0.036) and HBV DNA clearance after week 192 (HR: 0.11, 95% CI 0.02-0.64, p = 0.014) were associated with a reduce rate of HBeAg clearance; ALT > 5 times ULN (HR: 2.12, 95% CI 1.22-3.66, p = 0.007), HBV DNA ≥ 7 log10 UI/mL (HR: 6.18, 95% CI 1.18-69.60, p < 0.001), Metavir A score ≥ 2 (HR: 1.81, 95% 1.08-3.05, p = 0.024) were associated with an increased rate of HBeAg clearance (Table 3).

Baseline demographics characteristics according to HBeAg and HBsAg treatment response.

| HBeAg clearance | HBsAg clearance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | P value | Yes | No | P value | |

| Age (years) | 52 ±14 | 42 ± 11 | 0.001 | 57 ± 13 | 50 ± 13 | 0.029 |

| Gender (% Male) | 75 | 57 | 0.113 | 91 | 75 | 0.088 |

| Race (% Caucasian) | 74 | 58 | 0.220 | 95 | 83 | 0.114 |

| Median ALT values (lU/mL) | ||||||

| (25-75th percentile) | 130 (88-196) | 86 (56-132) | 0.0013 | 140 (79-243) | 95 (56-141) | 0.030 |

| ALT values > 5 times ULN (%) | 23 | 4 | 0.015 | 26 | 13 | 0.104 |

| Mean HBV DNA log (lU/mL) | 7,96 ± 1,16 | 7,41 ± 1,21 | 0.053 | 7,67 ± 1,26 | 6,75 ± 1,28 | 0.019 |

| HBV DNA ≥ 7 log lU/mL (%) | 86 | 69 | 0.050 | 78 | 55 | 0.033 |

| Mean Metavir A score | 2.1 ±0.7 | 1.5 ±0.5 | 0.001 | 2.5 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 0.001 |

| Metavir A score ≥ 2 (%) | 79 | 52 | 0.019 | 92 | 67 | 0.012 |

| Mean Metavir F score | 2.2 ±1.1 | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 0.383 | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 2.2 ± 1.2 | 0.399 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 19 | 10 | 0.265 | 5/18 | 33/113 | 0.008 |

ULN: upper limit of normal.

Predictors of HBeAg response, univariate analysis by Cox proportional hazard model.

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95CI% | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male vs. female) | 0.50 | 0.26 - 0.93 | 0.036 |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.98 - 1.01 | 0.769 |

| Race | 1.15 | 0.59 - 2.24 | 0.678 |

| Median ALT values (IU/mL) | 1.001 | 1.0002 - 1.0018 | 0.008 |

| ALT > 5 times ULN | 2.12 | 1.22 - 3.66 | 0.007 |

| Median HBV DNA (log10 IU/mL) | 1.6 | 1.35 - 1.89 | < 0.001 |

| HBV DNA ≥ 7 log10 UI/mL Median Metavir A score | 6.18 | 1.18 - 69.60 | < 0.001 |

| 1.67 | 1.16 - 2.41 | 0.006 | |

| Metavir A score ≥ 2 | 1.81 | 1.08 - 3.05 | 0.024 |

| Median Metavir F score | 0.97 | 0.78 - 1.22 | 0.849 |

| Cirrhosis | 0.35 | 0.41 - 1.34 | 0.339 |

| HBV negativization after week 192 | 0.11 | 0.02 - 0.64 | 0.014 |

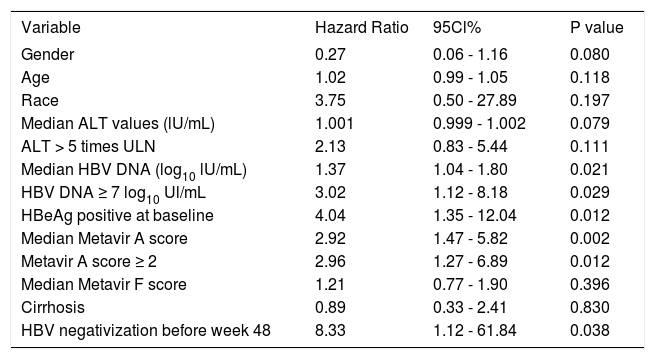

Patients achieving HBsAg clearance were older, have higher Metavir A scores, have less cirrhosis prevalence and have higher HBV DNA values than patients with persistent HBsAg (Table 2). In the univariate analysis HBV DNA ≥ 7 log10 UI/mL (HR: 3.02, 95% CI 1.12-8.18, p = 0.029), Metavir A score ≥ 2 (HR: 2.96, 95% 1.27-6.89, p = 0.012), HBeAg positive at baseline (HR: 4.04, 95% CI 1.35-12.04, p = 0.012), and HBV DNA negativization before week 48 (HR: 8.33, 95%CI 1.12-61.84, p = 0.038) were associated with an increased rate of HBsAg clearance (Table 4).

Predictors of HBsAg response, univariate analysis by Cox proportional hazard model.

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95Cl% | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.27 | 0.06 - 1.16 | 0.080 |

| Age | 1.02 | 0.99 - 1.05 | 0.118 |

| Race | 3.75 | 0.50 - 27.89 | 0.197 |

| Median ALT values (lU/mL) | 1.001 | 0.999 - 1.002 | 0.079 |

| ALT > 5 times ULN | 2.13 | 0.83 - 5.44 | 0.111 |

| Median HBV DNA (log10 lU/mL) | 1.37 | 1.04 - 1.80 | 0.021 |

| HBV DNA ≥ 7 log10 Ul/mL | 3.02 | 1.12 - 8.18 | 0.029 |

| HBeAg positive at baseline | 4.04 | 1.35 - 12.04 | 0.012 |

| Median Metavir A score | 2.92 | 1.47 - 5.82 | 0.002 |

| Metavir A score ≥ 2 | 2.96 | 1.27 - 6.89 | 0.012 |

| Median Metavir F score | 1.21 | 0.77 - 1.90 | 0.396 |

| Cirrhosis | 0.89 | 0.33 - 2.41 | 0.830 |

| HBV negativization before week 48 | 8.33 | 1.12 - 61.84 | 0.038 |

In the multivariate analysis, only baseline HBV DNA ≥ 7 log10 IU/mL (HR: 9.40, 95%CI 3.46-25.54, p < 0.001) and Metavir A score ≥ 2 (HR 2.48, 95% CI 1.39-4.40, p 0.002) remained statistically significant in predicting HBeAg clearance. Being HBeAg positive at baseline (HR 11.1, 95% CI 0.96-128, p 0.053) and HBV DNA clearance before week 48 (HR 7.76, 95% CI 0.96-62.4, p 0.054) tended to predict HBsAg seroclearance, but they were not statistically significant. The other variables evaluated did not help in predicting serologic response (Table 5).

Predictive factors of serological response, multivariate analysis by Cox proportional hazard model.

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95CI% | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HBeAg Clearance | |||

| Gender | 1.03 | 0.41 - 2.58 | 0.949 |

| ALT > 5 times ULN | 1.85 | 0.74 - 4.59 | 0.182 |

| HBV DNA ≥ 7 log10 IU/mL | 9.40 | 3.46 - 25.54 | <0.001 |

| Metavir A score ≥ 2 | 2.48 | 1.39 - 4.40 | 0.002 |

| HBV negativization after week 192 | 1.01 | 0.46 - 2.19 | 0.969 |

| HBsAg Clearance | |||

| HBeAg positive at baseline | 11.10 | 0.96 - 128 | 0.053 |

| HBV negativization before week 48 | 7.76 | 0.96 - 62.4 | 0.054 |

| Metavir A score ≥ 2 | 2.34 | 0.81 - 6.79 | 0.116 |

| HBV DNA ≥ 7 log10 IU/mL | 0.93 | 1.01 - 15.48 | 0.937 |

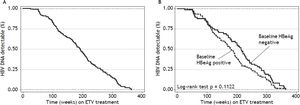

We have evaluated if any of baseline demographic characteristics and on-treatment response were associated with virologic response. There was no difference between virologic responders and non responders regarding age (51 ± 1 vs. 50 ± 4, p 0.737), gender (p 0.424), race (p 0.151), mean ALT levels [96 IU/mL (25-75th percentile, 56-152 IU/mL) vs. 100 IU/mL (25-75th percentile, 60-147 IU/mL) p 0.928], ALT levels ≥ 5 times ULN (p 0.133), mean HBV DNA levels (6.82 ± 1.73 log IU/mL vs. 7.69 ± 0.76 log IU/mL, p 0.090), HBV DNA levels ≥ 7 log IU/mL (p 0.213), Metavir A score (1.96 ± 0.78 vs. 1.63 ± 0.50, p 0.182), Metavir A score > 2 (p 0.207), Metavir F score (2.26 ± 1.21 vs. 2.33 ± 1.30, p 0.845), and presence of cirrhosis (p 0.456). None of the variables evaluated helped in predicting virologic response (Table 6). As expected, virologic responders received treatment for a longer median period of time than non responders: 189 weeks (25-75th percentile, 112-255 weeks) vs. 82 weeks (25-75th percentile, 55-147 weeks) respectively, p 0.0065. Patients receiving long term treatment would reach an HBV DNA clearance rate of 100% (Figures 1 and 2).

Predictive factors of virological response, univariate analysis by Cox proportional hazard model.

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95CI% | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.68 | 0.45 - 1.01 | 0.069 |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.97 - 1.001 | 0.093 |

| Race | 1.03 | 0.66 - 1.61 | 0.876 |

| Median ALT values (IU/mL) | 1.0001 | 0.99 - 1.0008 | 0.892 |

| ALT > 5 times ULN | 1.28 | 0.83 - 1.97 | 0.255 |

| Median HBV DNA (log10 IU/mL) | 1.02 | 0.93 - 1.13 | 0.582 |

| HBV DNA ≥ 7 log10 UI/mL HBeAg negative at baseline | 1.26 | 0.91 - 1.75 | 0.161 |

| 1.29 | 0.93 - 1.79 | 0.114 | |

| Median Metavir A score | 1.20 | 0.92 - 1.58 | 0.169 |

| Metavir A score ≥ 2 | 1.48 | 0.92 - 2.29 | 0.070 |

| Median Metavir F score | 1.002 | 0.86 - 1.16 | 0.973 |

| Cirrhosis | 0.88 | 0.60 - 1.29 | 0.537 |

The main end point of chronic HBV treatment with NUCs is complete viral suppression. Once HBV DNA is cleared, continuing treatment may achieve HBeAg clearance and antiHBe seroconversion in HBeAg positive patients and less frequently HBsAg clearance and antiHBs seroconversion, in both HBeAg positive and negative patients.3,4 In our study, we were able to demonstrate that long term treatment with ETV in clinical practice is safe and effective, and it is associated with increasing rates of HBV DNA, HBeAg and HBsAg clearance.

Pivotal studies demonstrated that ETV is an antiviral agent of high clinical potency. At a dose of 0.5 mg/day in treatment-naive patients suppressed HBV DNA to undetectable levels by year 1 in 67% of HBeAg-positive and in 90% of HBeAg-negative patients.5,6 A randomized controlled trial showed that prolonging treatment resulted in a better HBV DNA suppression. When administered for 96 weeks in HBeAg positive patients, 80% of the patients achieved HBV DNA levels < 300 copies/mL. In addition, approximately 31% of patients achieved HBeAg seroconversion, 5% achieved HBsAg negativization, and 2% achieved HBsAg seroconversion by week 96.7 Treatment for longer periods of time in the study ETV 901 (up to 5 years) was associated with 94% HBV DNA, 23% HBeAg and 1.4% HBsAg clearance rates.8

Industry sponsored RCT showed that ETV treatment is safe and effective. Studies were performed in routine clinical practice (also called “real life” studies) trying to confirm if these results are applicable to the general population. Most of the studies were from Europe and Asia.11–20 Treatment for 48 weeks in Spain was associated with 82% HBV DNA negativization, 26% HBeAg and 2% HBsAg clearance rates in 190 NUC-naïve patients.11 In France, treatment of 418 consecutive NUC-naïve patients for 240 weeks reported 100% HBV DNA negativization, 55% HBeAg and 33% HBsAg clearance rates.14 In Italy, 100 treatment-naïve patients achieved 94% HBV DNA negativization, 33% HBeAg and 15% HBsAg clearance rates after 144 weeks of continuous ETV treatment.15 Results from Hong Kong showed that 222 treatment-naïve patients achieved 92% HBV DNA negativization, 44% HBeAg and 0.45% HBsAg clearance rates after 144 weeks of continuous ETV treatment (16). In Japan, 474 treatmentnaïve patients obtained 96% HBV DNA negativization and 42% HBeAg clearance rates after 192 weeks treatment.17 Finally, 230 NUC-naïve patients treated in China for 240 weeks achieved 100% HBV DNA negativization, 15% HBeAg and 0.40% HBsAg clearance rates.18 Our results are consistent with experiences in other parts of the world, showing increasing virological and serological response rates with continuous treatment.20 Conversely other studies in clinical practice described lower HBeAg clearance and seroconversion rates, even with prolonged treatment.21,22

All these studies showed, as we report, a very low incidence of ETV resistance and virological breakthrough: < 1%. These results are similar to those reported from patients from six phase 2 and 3 clinical studies: the 5-year cumulative probability of genotypic resistance to ETV in NUC-naïve patients was 1.2% whereas among lamivudine-refractory patients was 57%.9 Also ETV treatment for long term appears to be safe in clinical practice as reported from clinical trials.23–25 There were no serious side effects and no patients discontinued ETV due to intolerance.

After ETV discontinuation, 9 of 35 patients (26%) developed virological relapse. All patients were HBeAg positive at baseline, 4 showed antiHBe seroreversion and 3 of them showed HBeAg positivization. At the end of follow up 10% developed serological relapse, all relapsers showed HBeAg positivization. None of the patients developed HBsAg relapse. These findings suggest that, even after consolidation therapy and HBeAg seroconversion, patients must be strictly followed since HBV DNA may relapse. More detail information about outcomes after treatment discontinuation have been recently published.26

Several baseline and on-treatment factors had been found to predict virological and serological response.27,28 We found various predictors of serological treatment response with long term treatment, but only Metavir A score > 2 and HBV DNA ≥ 7 log10 IU/mL predicted HBeAg clearance in the multivariate analysis. HBeAg clearance and HBV DNA clearance before week 48 of treatment were associated with HBsAg clearance, but these predictors were close to statistical significance. In clinical practice, ALT > 5 times ULN and HBV DNA < 7 log10 IU/mL had been associated with HBV DNA clearance at weeks 48 and 96.15,17,18 HBeAg clearance was also associated with HBV DNA < 7 log10 IU/mL and ALT > 5 times ULN.17,29 Since almost all patients achieved HBV DNA clearance with long term treatment, no factor predicted virological response. We did not find predictors of HBV DNA response at week 48 of treatment, and only HBV DNA ≥ 7 log10 IU/mL predicted HBV DNA clearance at week 96 (data not shown).

This study has some limitations. Even though patients are prospectively followed, it is a retrospective study with a limited number of patients. Also, we did not measure HBsAg levels at baseline and during treatment, or analyzed which low HBsAg baseline values and on treatment response might have been associated with virological and serological response rates.30

There is a discussion if results of RCTs can be extrapolated to the everyday clinical practice. These studies, despite sound internal validity, may not have good external validity (generalisability) in general population.31 As we and others authors have shown, long term treatment of chronic HBV in real life can be as safe and effective as in RCT.

AcknowledgementsWe are indebted to Dr. Hugo Krupitzky for his help with the statistical analysis.

Ezequiel Ridruejo acts as guarantor of the submission. All co-authors have contributed to the recruitment of patients, gathering and submission of data. All participated in the manuscript drafting and subsequent revisions, and had complete access to the data that support the publication. All co-authors agreed with the submitted version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Personal and Funding InterestsNone.