Introduction. Patients with primary antibody deficiency (PAD) can complicate with liver disease. This study was performed in order to study the prevalence and causes of hepatobiliary diseases in Iranian patients with PAD.

Material and methods. Sixty-two patients with PAD were followed-up and signs and symptoms of liver disease were recorded. All patients were screened for hepatitis C virus (HCV-RNA) and those patients with any sign of liver disease or gastrointestinal complaints were tested for Cryptosporidium parvum.

Results. Clinical evidences of liver disease, including hepatomegaly, were documented in 22 patients (35.5%). Eight patients (13%) had clinical and/or laboratory criteria of chronic liver disease. Only one patient was HCV-RNA positive; he had stigmata of chronic liver disease and pathologic evidence of chronic active hepatitis with cirrhosis. Cryptosporidium parvum test was positive for one patient with hyper-IgM syndrome. In liver biopsy of patients with liver involvement, one had histological findings related to sclerosing cholangitis, and five had mild to moderate chronic active hepatitis with unknown reason.

Conclusions. Chronic active hepatitis is the most common pathologic feature of liver injury in Iranian patients with PAD. Liver disease in PAD usually accompanies with other organ involvements and could increase the mortality of PAD. Whether this high rate of liver disease with unknown origin (75%) is the result of an unidentified hepatotropic virus or other mechanisms such as autoimmunity, is currently difficult to understand.

Primary immunodeficiency diseases (PID) include a heterogeneous group of disorders that render the host to be susceptible to a wide set of infections. Primary antibody deficiencies (PAD) are the most common forms of PID in human,1-3 with a wide spectrum, ranging from severe reduction of all serum immunoglobulins with absence of B cells to a selective antibody deficiency with normal serum immunoglobulins.4 Failure of antibody production in PAD patients causes chronic and recurrent bacterial infections most notably in respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts.5-11

Delay in diagnosis and inadequate treatment cause severe complications and irreversible organ damages resulting in increased morbidity and mortality,12-19 while early diagnosis and use of immunoglobulin replacement therapy reduce serious bacterial infections in these group of patients.13,20-22

Liver involvement either may be a clinical manifestation or considered as a life threatening complication of primary immunodeficiencies. The incidence of liver disease (LD) in all types of PID varies from 18 to 55% in several documented studies.14-16,23,24 Hepatobiliary complications range from mild biochemical abnormalities to end-stage liver disease and mainly caused by hepatotropic viruses (HCV),25-28Cryptosporidiumparvum29 and autoimmunity.30

In the present study, we described the spectrum of hepatobiliary disorders in a large group of well-characterized Iranian patients with primary antibody deficiencies. The aim of this study was to investigate the mode of presentation, clinical features, etiology, and the outcome of liver disease among patients with primary antibody deficiencies.

Material and MethodsSubjectsSixty-two patients with PAD whom were diagnosed and followed up during a 20 years period (19852006) were enrolled in this study.

The diagnosis of primary antibody deficiency was based on diagnostic criteria of PAGID (the Pan-American Group for Immunodeficiency) and ESID (the European Society for Immunodeficiencies).31 The diagnosis of patients with X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA) and hyper-IgM syndromes (HIGM) has been confirmed by mutation analysis.

All patients had been routinely screened for infectious and non-infectious related complications periodically during their follow up. Concerning liver disease, this screening included serum concentrations of aminotransaminases (ALT, AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), bilirubin, albumin and coagulation tests (PT, PTT), that were performed at least twice yearly.

Study DesignDuring the current study period (May 2005 until September 2006), alive patients were investigated with focus on clinical and laboratory features of liver involvement. A questionnaire was designed that included the demographic data, the diagnosis, age at onset, diagnostic delay, and the results of clinical and laboratory findings.

The liver injury documented based on, at least two-fold increase of serum levels of aminotransferases (ALT, AST). Chronicity was defined with persistent elevation of aminotransferases for at least six months or presence of chronic liver disease stigmata such as stiffness and nodularity of liver, or enlargement of left liver lobe, clubbing, palmar erythema and spider angioma, at the first examination.14,16,32

Screening the Hepatitis C VirusAll patients (except P4 who was not alive during the time of study) were screened for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection using HCV-PCR technique described in detail elsewhere.33,34 HCV cDNA was obtained by reverse transcription from HCV mRNA using the synthetic primer NCR2 located in the highly conserved 5’ non-coding region of the HCV genome.

Screening of Cryptosporidium parvumThe screening of Cryptosporidium parvum in stool specimens was performed in patients with any sign of liver disease or gastrointestinal complaints. This screening was based on detection of oocysts by light microscopy (with modified Ziehl-Neelsen staining), and was documented with PCR modality.29

Other InvestigationsWe looked for other causes of liver involvement (autoimmune hepatitis, HBV infection, CMV infection, primary biliary disease, metabolic liver disease, obesity, drug induced hepatitis and malignancies) if the results of screening for HCV and C. parvum were negative. None of the patients had signs of any systemic infections at the time of study.

Abdominal ultrasound exam and percutaneous liver biopsy under sedation were performed in the presence of chronic liver disease stigmata at the first examination, positive result for HCV infection, or at least two-fold increase of serum levels of aminotransferases (ALT, AST) for over six months.

Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) performed if the patient had C. parvum in stool or dilatation of biliary system on ultrasonography to rule out the sclerosing cholangitis.

Statistical MethodsStatistical analysis was performed using the chisquare test. Survival curve was illustrated according to the Kaplan-Meier method.

ResultsPatients’ CharacteristicsSixty-two patients with PAD, including: 38 patients with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID), 19 with XLA and five with HIGM, were introduced. There were 48 males and 14 females; the median age of patients was 10.3 years (range 2-56). Forty six patients (75%) were under 18 years. Patients were followed-up for a mean of five years (range 0.2-19 years).

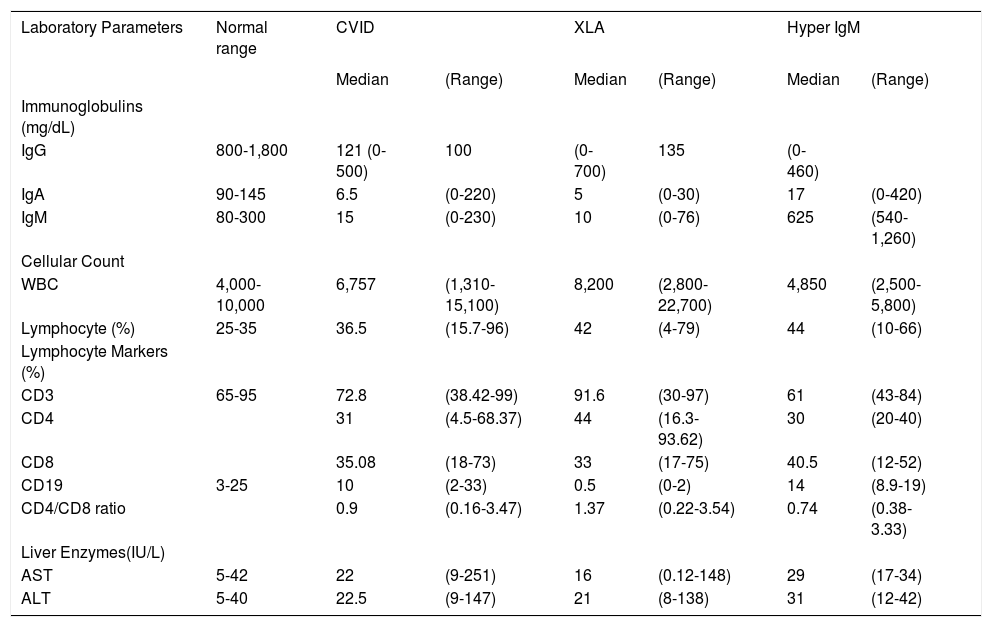

Baseline laboratory findings, including serum immunoglobulin levels and immunophenotyping of peripheral blood lymphocytes, are summarized in the table 1.

Laboratory parameters in patients with primary antibody deficiencies.

| Laboratory Parameters | Normal range | CVID | XLA | Hyper IgM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | (Range) | Median | (Range) | Median | (Range) | ||

| Immunoglobulins (mg/dL) | |||||||

| IgG | 800-1,800 | 121 (0-500) | 100 | (0-700) | 135 | (0-460) | |

| IgA | 90-145 | 6.5 | (0-220) | 5 | (0-30) | 17 | (0-420) |

| IgM | 80-300 | 15 | (0-230) | 10 | (0-76) | 625 | (540-1,260) |

| Cellular Count | |||||||

| WBC | 4,000-10,000 | 6,757 | (1,310-15,100) | 8,200 | (2,800-22,700) | 4,850 | (2,500-5,800) |

| Lymphocyte (%) | 25-35 | 36.5 | (15.7-96) | 42 | (4-79) | 44 | (10-66) |

| Lymphocyte Markers (%) | |||||||

| CD3 | 65-95 | 72.8 | (38.42-99) | 91.6 | (30-97) | 61 | (43-84) |

| CD4 | 31 | (4.5-68.37) | 44 | (16.3-93.62) | 30 | (20-40) | |

| CD8 | 35.08 | (18-73) | 33 | (17-75) | 40.5 | (12-52) | |

| CD19 | 3-25 | 10 | (2-33) | 0.5 | (0-2) | 14 | (8.9-19) |

| CD4/CD8 ratio | 0.9 | (0.16-3.47) | 1.37 | (0.22-3.54) | 0.74 | (0.38-3.33) | |

| Liver Enzymes(IU/L) | |||||||

| AST | 5-42 | 22 | (9-251) | 16 | (0.12-148) | 29 | (17-34) |

| ALT | 5-40 | 22.5 | (9-147) | 21 | (8-138) | 31 | (12-42) |

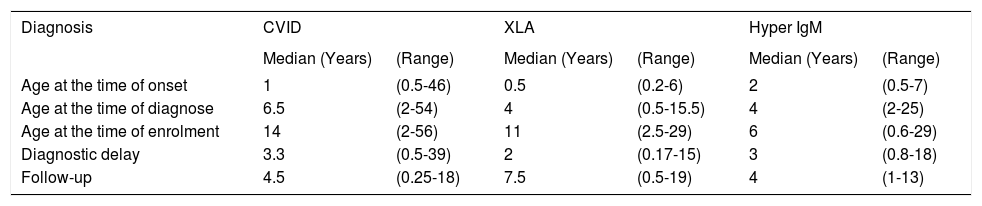

The time elapsed between onset of clinical symptoms and diagnosis of antibody deficiency (diagnostic delay) was 39 months for CVID, 24 months for XLA, and 36 months for HIGM. Age at onset of disease, diagnostic age, delay in diagnosis, follow up period and current age of patients are recorded in the table 2.

Diagnostic parameters in patients with primary antibody deficiencies.

| Diagnosis | CVID | XLA | Hyper IgM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (Years) | (Range) | Median (Years) | (Range) | Median (Years) | (Range) | |

| Age at the time of onset | 1 | (0.5-46) | 0.5 | (0.2-6) | 2 | (0.5-7) |

| Age at the time of diagnose | 6.5 | (2-54) | 4 | (0.5-15.5) | 4 | (2-25) |

| Age at the time of enrolment | 14 | (2-56) | 11 | (2.5-29) | 6 | (0.6-29) |

| Diagnostic delay | 3.3 | (0.5-39) | 2 | (0.17-15) | 3 | (0.8-18) |

| Follow-up | 4.5 | (0.25-18) | 7.5 | (0.5-19) | 4 | (1-13) |

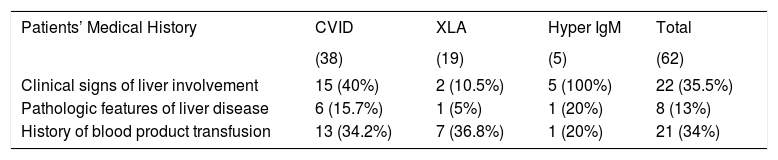

Patients received intravenous immunoglobulin for mean period of 5.2 years (range: 2-19 years). Twenty-one patients (34%) had received other products of blood such as packed red blood cells, platelet or fresh frozen plasma. The prevalence of blood product transfusion was not significantly different (P value > 0.05) in each type of PID (Table 3).

Liver involvement in antibody deficient patients.

| Patients’ Medical History | CVID | XLA | Hyper IgM | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (38) | (19) | (5) | (62) | |

| Clinical signs of liver involvement | 15 (40%) | 2 (10.5%) | 5 (100%) | 22 (35.5%) |

| Pathologic features of liver disease | 6 (15.7%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (20%) | 8 (13%) |

| History of blood product transfusion | 13 (34.2%) | 7 (36.8%) | 1 (20%) | 21 (34%) |

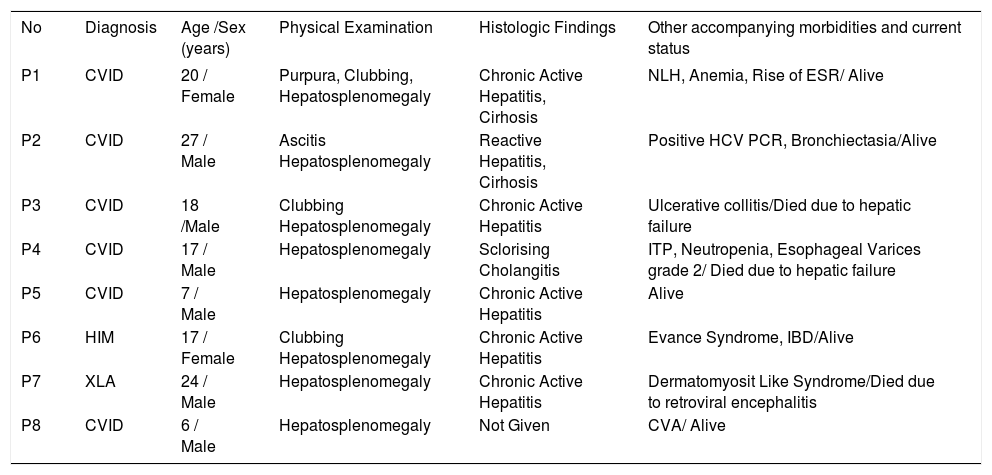

Among 62 studied patients, 22 patients (35.5%) had clinical features in favor of chronic liver disease, including hepatomegaly. These patients include five HIGM (100%), 15 CVID (40%) and two XLA (10.5%) patients (Table 3). Percutaneous liver biopsy was performed that revealed abnormalities in eight of them (13%) (Table 4).

Clinical features of primary antibody deficient patients with chronic liver disease.

| No | Diagnosis | Age /Sex (years) | Physical Examination | Histologic Findings | Other accompanying morbidities and current status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | CVID | 20 / Female | Purpura, Clubbing, Hepatosplenomegaly | Chronic Active Hepatitis, Cirhosis | NLH, Anemia, Rise of ESR/ Alive |

| P2 | CVID | 27 / Male | Ascitis Hepatosplenomegaly | Reactive Hepatitis, Cirhosis | Positive HCV PCR, Bronchiectasia/Alive |

| P3 | CVID | 18 /Male | Clubbing Hepatosplenomegaly | Chronic Active Hepatitis | Ulcerative collitis/Died due to hepatic failure |

| P4 | CVID | 17 / Male | Hepatosplenomegaly | Sclorising Cholangitis | ITP, Neutropenia, Esophageal Varices grade 2/ Died due to hepatic failure |

| P5 | CVID | 7 / Male | Hepatosplenomegaly | Chronic Active Hepatitis | Alive |

| P6 | HIM | 17 / Female | Clubbing Hepatosplenomegaly | Chronic Active Hepatitis | Evance Syndrome, IBD/Alive |

| P7 | XLA | 24 / Male | Hepatosplenomegaly | Chronic Active Hepatitis | Dermatomyosit Like Syndrome/Died due to retroviral encephalitis |

| P8 | CVID | 6 / Male | Hepatosplenomegaly | Not Given | CVA/ Alive |

NLH: Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia. ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate. IBD: Inflamatory bowel disease. ITP: Immune-mediated thrombocytopenic purpura. CVA: Cerebrovasculare accident.

Inflammatory bowel diseases (P3, P6), other autoimmune diseases (P1, P4, P6, P7), and bronchiectasis (P2) were common in this group of patients, while other patients did not experience such manifestations (Table 4).

The presences of liver abscess, liver mass or any sign of fatty liver were excluded by abdominal ultra-sonography.

Laboratory StudiesElevations of amino transaminases (ALT, AST) were found in 10 patients (16%). This rising was transient in four patients (whom were negative for HCV RNA). Two of them were considered as drug-induced hepatitis. The enzyme levels became normal after discontinuation of the drug (clarithromycin) and no other etiology was detected in them. Six patients had persistent (above six months) elevated levels of serum amino transaminases (mean for ALT: 159 IU/L and for AST: 109 IU/L) (Table 4).

HCV infection was detected only in one patient who had CVID and suffered from end stage liver disease (P2). All patients were negative for HBsAg.

In examination of stool, only one patient with HIGM due to CD40-ligand deficiency was positive for C. parvum. This patient had hydrops of gall bladder in ultrasonography but he was asymptomatic with normal liver enzymes. Sclerosing cholangitis ruled out using MRCP in this patient.

Further DetailsIn general, pathologically proved liver disease was found in eight out of 62 patients (13%) with median age of 15 years. All of them had abnormal clinical examination in favor of liver disease, six patients had persistent elevation of amino transaminases (ALT, AST) and two patients had normal level of liver enzymes. These later two patients (P2, P6) had history of increased level of amino transaminases (ALT, AST) since some years ago and had palmar erythema, clubbing and ascites due to chronic liver dysfunction in first clinical examination (Table 4).

Among the eight patients with proved liver diseases, seven patients underwent percutaneous liver biopsy. The remaining one patient declined liver biopsy. The microscopic evaluation of liver biopsies showed mild to moderate chronic active hepatitis in five patients, which were not compatible with any specific etiology. One patient (P4) had histological evidences of sclerosing cholangitis and died due to severe hepatic insufficiency. In remaining patient (P2) with HCV infection, liver biopsy had been performed four years before our study, and showed reactive hepatitis with fibrosis indicating liver cirrhosis. This patient developed esophageal varices grade n, end stage liver disease, and cachexia.

As it has been shown in table 4, the known causes of liver disease were hepatitis C infection (P2) and sclerosing cholangitis (P4). In remaining six patients, no etiology were found (75%). There was no meaningful relationship between liver involvement and type of primary antibody deficiency.

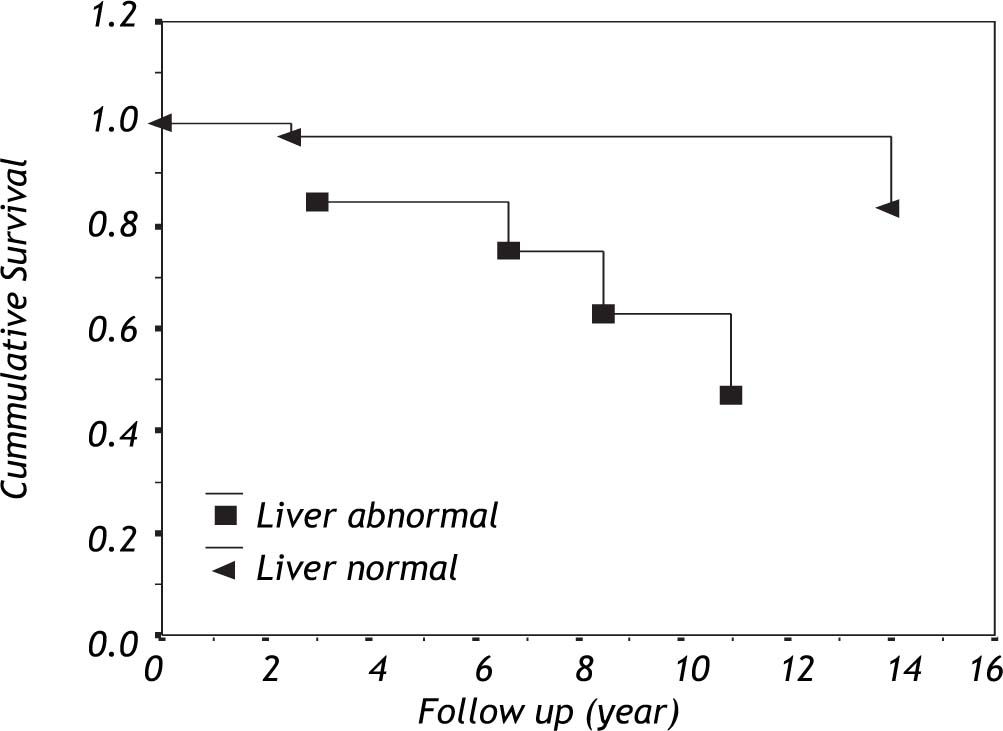

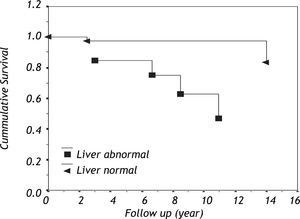

The cumulative survival within patients with primary antibody deficiency based on liver involvement is shown in figure 1. Among eight patients who complicated with liver disease, three (37.5%) died during their follow-up.

DiscussionThe incidence of liver involvement in patients with primary immunodeficiency varies from 18% to 55%14,32 and its severity ranging from mild biochemical abnormalities to end-stage hepatic failure.14-16,23,35,36 In our current study, the prevalence of liver diseases in 62 patients with primary antibody deficiency was 13%, which supports previous studies.

Fiore M, et al.15 in 1998 studied 30 Italian children (> 16 years) with PID (T cell, B cell and combined immunodeficiency). Their study showed that 11 patients (36.8%) had liver disease including 10 patients with T-cell and one with B-cell (CVID) deficiency. Also in another study which was performed by an American group,16 among the 147 patients with PID (> 18 years), 35 patients (26%) were detected to have liver involvement. The most common type of PID was combined immunodeficiency syndrome (14 out of 35), in the reported study. All these data show that the involvement of liver in patients with T-cell and combined immunodeficiencies is more common and more severe comparing with primary antibody deficiencies.37

HCV infection was a major cause of liver disease in hypogammaglobulinemic patients in the past. Between February and July of 1994, 112 cases of hepatitis C infection associated with the use of infected IVIG were reported to the CDC,27 as well as some reports from Europe.25,32 Recent data clearly show that most immunoglobulin preparations are acceptably safe, at least with regard to HIV, HBV and HCV transmission,38 as we found only one patient infected with hepatitis C.

Our data provide evidence that a remarkable number of patients with primary antibody deficiency have liver disease unrelated to the common hepatotropic pathogens (Table 4).

Previous reports showed that sclerosing cholangitis (SC) is a common feature of liver involvement associated with immune disorders.23,24,39,40C. parvum had been implicated in the development of SC in HIV infection and in other immunocompromised patients, in particular, in those with X-linked HIGM syndrome.35,36 In our study, C. parvum infection was found in one patient. This patient had X-linked HIGM syndrome, was asymptomatic and had no laboratory and radiological evidence of sclerosing cholangitis and treated with azythromycin. The low incidence of C. parvum infection in our study could be due to geographical situations and good care of patients.

The rising of serum amino transaminases (ALT, AST) is characteristic of liver involvement. The level of this rising indicates the severity of hepatocellular injury.41 Based on results of our study and those from others,14-16,32,42 persistent elevation of liver enzymes in patients with primary antibody deficiency, above two times greater than normal, is an indicator of liver involvement and can be the first sign of an unknown progressive systemic disease. Chronic active hepatitis with unknown origin was the most common feature of liver injury in our series (75%). Because of high incidence of liver involvement, it is advised to perform a biochemical liver profile, including serum concentrations of amino transaminases must be performed at least twice yearly in all patients with primary antibody deficiency.43

The presence of autoantibodies like smooth muscle antibody (SMA) is usual in PID specially in T-cell deficiencies that can reflect dysregulation in immune system and may involve the liver.5,14,16,30,44 Triggering of autoimmune inflammatory processes by hepatotropic viruses is one possible mechanism by which such chronic liver disease may develop.14,44 Since in primary antibody deficiencies, production of antibodies is impaired, we cannot detect autoantibodies in these patients. High incidence of other co-morbidities such as bone marrow suppression, autoimmune cytopenias, inflammatory bowel diseases and dermatomyositis like syndrome can propose that a systemic autoimmune process is present.

More investigations are needed to determine etiology of this high prevalence of unexplained liver disease (75%) and unknown progressive systemic disease. Interestingly, the survival of PAD patients with liver involvement seems to be less than that of patients who do not have this complication. Application of preventive measures and beginning of timely therapy for this complication could lead to increased life span of PAD patients.

Other reports revealed that approximately 10 to 23% of adult patients with some types of primary immunodeficiency have unexplained liver diseases.14,15,32 Chronic active hepatitis is the most common pathologic feature of liver injury in our patients with primary antibody deficiency (five from seven patients). Whether this high prevalence of liver disease with unknown origin (75%) is the result of an unidentified hepatotropic virus or other mechanisms such as autoimmunity, is currently difficult to understand.

AcknowledgmentsThis study was supported by a grant from Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Immunology, Asthma and Allergy Research Institute.

The authors wish to thank all the patients, their families and the Iranian Primary Immunodeficiency Association (IPIA) for their kind collaboration in this research project. We are also grateful to Dr. Memar, Dr. Jannati, Dr. Arshi, Ms. Akbarzadeh, and Ms. Faridoni and the staff of the Department of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Tehran University of Medical Sciences.