Renal dysfunction frequently occurs in liver transplant recipients and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. BK virus is a human polyoma virus that reactivates during immunocompromised states and is a known cause of renal allograft dysfunction in renal transplant recipients. However, BK nephropathy of native kidneys is rare in non-renal transplant recipients. There is no published data linking BK virus and renal dysfunction in liver transplant recipients. We describe the first confirmed case of native polyomavirus BK nephropathy in a liver transplant recipient. BK nephropathy should be considered in the differential diagnosis of new renal failure in liver transplant recipients.

Patients frequently develop chronic kidney disease (CKD) after liver transplantation with a reported prevalence of 10-40%.1 Chronic renal insufficiency in liver transplant patients is associated with adverse outcomes and has become a leading cause of morbidity and mortality.2 Common risk factors for the development of progressive CKD or end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in long-term survivors of OLT include calcineurin (CNI) nephrotoxicity, hepatorenal syndrome, hepatitis C infection, pre-existing renal dysfunction, perioperative renal injury, and the development of hypertension or diabetes mellitus post transplantation.3

BK nephropathy is an important cause of renal dysfunction in renal transplant recipients but is uncommon in non-renal solid organ transplant patients. Several recent studies have reported BK virus reactivation is not associated with renal insufficiency in liver transplant recipients.4–6 We report the first case of confirmed BK nephropathy of the native kidney in a liver transplant recipient. This case report and brief review of literature highlight that BK nephropathy should be included in the differential diagnosis of new renal insufficiency in post liver transplant recipients.

Case ReportA 59 year-old Caucasian man, with a history of liver transplant seven years previously for end stage liver disease secondary to primary sclerosing cholangitis, was referred for acute kidney injury. His post transplant course was complicated by multiple episodes of acute graft rejections. The first was within the first year post-transplant followed by five episodes of late acute rejection, three to five years post transplant. All episodes were biopsy confirmed and responded to treatment with pulse corticosteroids. Maintenance immunosuppression was intensified to include: higher dose mycophenolate mofetil 1,500 mg bid, tacrolimus (trough of 10-12 ug/L), sirolimus (trough of 8-12 ug/L) and prednisone. Other past medical history included Crohn’s disease, which was quiescent. Other medications included ASA 81 mg daily, ursodiol 500 mg twice daily.

His baseline serum creatinine was 90 umol/L and progressively climbed to 165 umol/L (eGFR 37 mL/ min) over the course of three to six months prior to referral. His renal dysfunction was initially assumed to be CNI induced nephrotoxicity and his tacrolimus dose was decreased. However, as the renal function failed to improve despite a 50% dosage reduction, he was referred to the nephrology service.

From a renal perspective, he was asymptomatic and the history was unremarkable for pre-renal or post renal causes of renal dysfunction. On physical examination, he was euvolemic with a blood pressure of 130/80. Laboratory results revealed a hemoglobin level of 125g/L, mild thrombocytosis at 534 × 109 per L and normal electrolytes. His liver biochemistry and bilirubin were normal. Cytomegalovirus was undetectable. Urine albumin creatinine ratio was 3.3 mg/mmol. Complement C3 and C4, serum protein electrophoresis were normal. Urinalysis revealed 4 + blood and 1+ protein. Microscopy showed numerous red blood cells, most of which were uniform however a few displayed dysmorphic features. Granular casts were also present. His renal ultrasound revealed normal sized kidneys with no hydronephrosis.

A glomerulonephritis workup revealed atypical perinuclear-ANCA and a markedly elevated proteinase 3 antibody (PR-3) titre (76 units). ANA, ENA and anti-GBM Ab were negative. Although PR-3 and positive ANCA may have represented a false positive due to his underlying primary sclerosing cholangitis and Crohn’s disease, ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis could not be excluded. Thus an urgent renal biopsy was performed.

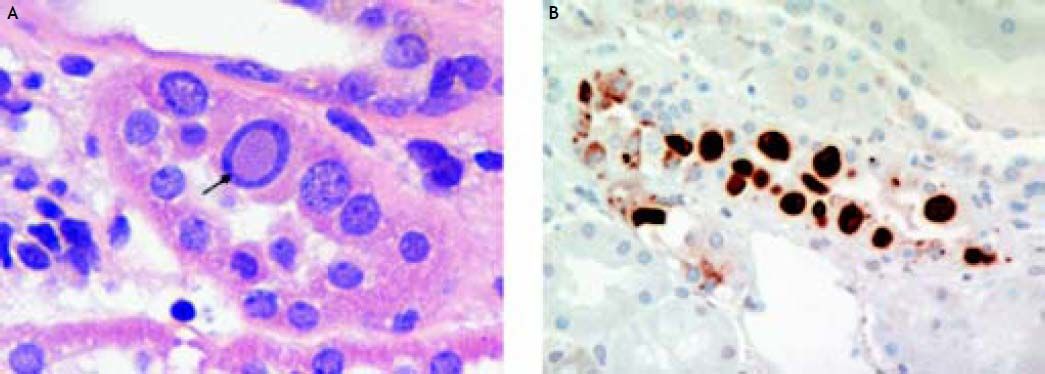

The findings on renal biopsy were in keeping with polyoma virus BK nephropathy, University of Maryland class B2.7 Twenty-six glomeruli were present of which three were obsolete and the rest were unremarkable. About 40 percent of the cortex showed chronic tubular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis and a mononuclear cell interstitial infiltrate. Some tubules both within scarred and non-scarred areas were lined by epithelial cells with enlarged nuclei containing basophilic inclusions (Figure 1A). Immunostaining demonstrated focal positive tubular epithelial nuclear staining for the simian virus (SV) 40 T antigen which shares epitopes with the large T antigen of polyoma BK and JC viruses8 (Figure 1B). Focal arteriolar hyalinosis was noted.

A. The tabulus contains a cell with enlarged nucleus containing a viral inclusion (arrow). (H&E stain, original magnification × 400). B. Immunostaining for polyoma virus shows strong nuclear reactions in several cells in a tubule. (Immunoperoxidase stain, original magnification × 400).

Direct IF showed no glomerular, tubular basement membrane or vascular staining for IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, C1q, fibrinogen and kappa and lambda light chains. Tissue taken for EM did not contain epithelial nuclei with viral inclusions. The serum BK virus viral load was found to be 2.4million copies/mL using an in-house quantitative real time PCR assay based on methods previously reported.9

DiscussionBK virus (BKV) is a ubiquitous, small DNA virus belonging to the polyomavirus family. Primary infection with BKV is usually asymptomatic in immunocompetent patients and commonly infects young children.10 The exact mode of transmission is unclear but is thought to be through oral or respiratory exposure. After primary infection the virus remains dormant in renal epithelium and lymphocytes.11 Seroprevalence studies from North America and Europe indicate that 60-80% of adults are infected with BKV.12 However, BKV causes clinical disease mostly in the setting of immunosuppression.

In 1971 Gardner, et al. first isolated BKV from the urine of a Sudanese renal transplant recipient (with the initials B.K.) who developed ureteral stenosis.13 Since then, BK nephropathy has been extensively studied and reviewed in renal transplant recipients. BK nephropathy develops in renal transplant recipients usually within one year post transplant and in up to 90% of these patients will lead to acute rejection.10 BKV causes tubulointerstitial nephritis and ureteral stenosis in renal transplant recipients. Patients with BKV interstitial nephritis most commonly present with an asymptomatic acute or slowly progressive rise in the serum creatinine concentration. Hematuria may be present. Over immunosuppression appears to be the most important risk factor for development of BK nephropathy.14 However, other risk factors may be associated including older and younger age, male gender, acute rejection episodes and HLA or ABO incompatibility.15,16

BK nephropathy involving native kidneys of nonrenal solid organ transplant recipients is rare, but have been reported in heart, lung, pancreas, and stem cell transplant recipients.17–19 To date, there has been no convincing published data linking BK virus to renal dysfunction among liver transplant recipients despite the fact BK virus reactivation is common in the liver transplant population.5,20 A cross-sectional study among 41 liver transplant patients with an average of 6.5 years post-transplant reported 24% of patients had viruria but no cases of viremia. They found no relationship between the presence of BKV in the urine and renal function.4 A prospective incidence study by Doucette, et al., that included 25 liver transplant patients, did not observe any association between BK viruria and renal dysfunction.5 Two other prospective studies in pediatric liver transplant patients also reported that neither BK viruria nor viremia was associated with impairment in renal function.6 A prospective study by Loeches, et al. reported the highest incidence of BK viremia (18%) and viruria (21%) in 62 liver transplant patients.21 They observed that BK viremia was more common among patients after rejection episodes, which may have been due to necessary increased immunosuppression. Overall, however, they found no relationship between episodes of BKV viremia and renal function, although three patients with persistent BK viremia developed renal insufficiency. In two of the cases, the renal failure was attributed to CNI toxicity, and renal function improved after reduction of immunosuppression. Unfortunately, renal biopsies were not performed on any patients, which prevented the authors from detecting any definite cases of BK nephropathy.

To our knowledge, our patient is the first confirmed case of BK nephropathy in a liver transplant recipient. The lack of confirmed cases of BK nephropathy in liver transplant patients to date may be that it is under diagnosed. Renal biopsies are not routinely performed in liver transplant recipients since progressive renal dysfunction is often attributed to the toxicity of calcineurin inhibitors and patient comorbidities. Based on the previous negative post-liver transplant studies, we suspect that BK nephropathy post liver transplant may also be a rare event as it has been postulated that a second hit resulting to renal damage in addition to immunosuppression is necessary for the development of BK nephropathy.5 The low incidence of BK nephropathy, when combined with a general lack of clinical suspicion and under diagnosis, may also explain paucity of reported cases in the medical literature.

In our patient’s situation, the increased immunosuppression regimen with four medications including a higher dose of MMF likely contributed to the development of BK nephropathy despite the fact that he was many years post-liver transplant. Since there is currently no antiviral therapy specifically licensed for the treatment of BKV infections, the management is to reduce immunosuppression.

ConclusionKidney disease is a prevalent complication after liver transplantation and is associated with a substantial mortality risk. BKV reactivation occurs in liver transplant recipients and BK nephropathy should be considered in liver transplant recipients presenting with new renal insufficiency.